Volume 5, Issue 2 (2024)

J Clinic Care Skill 2024, 5(2): 69-75 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/05/6 | Accepted: 2024/06/18 | Published: 2024/06/30

Received: 2024/05/6 | Accepted: 2024/06/18 | Published: 2024/06/30

How to cite this article

Mohammadi S, Pajohideh Z, Rabiei Z. Adolescent-Specific Prenatal Clinics' Effectiveness in Improving Birth Outcomes; A Systematic Review. J Clinic Care Skill 2024; 5 (2) :69-75

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-255-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-255-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Adolescent-Specific Prenatal Clinics' Effectiveness in Improving Birth Outcomes; A Systematic Review

1- Reproductive Health Promotion Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

2- Department of Midwifery, Shoushtar Faculty of Medical Sciences, Shoushtar, Iran

3- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Iran

2- Department of Midwifery, Shoushtar Faculty of Medical Sciences, Shoushtar, Iran

3- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (1545 Views)

Introduction

Adolescence is a distinct and unique stage of development in a woman's life. Consequently, diagnosing and managing pregnancy during this period requires identifying risk factors and understanding the necessary elements of care for successful outcomes for both mother and infant [1]. An adolescent pregnancy refers to a pregnancy that occurs between the ages of 10-19 years. The majority of adolescent pregnancies occur specifically between the ages of 15-19 years [2]. In 2018, the global adolescent birth rate was estimated at 44 births per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 [3]. The adolescent pregnancy rate in Iran in the 1960s was about 150 pregnancies per 1,000 adolescents, but it had decreased to 26 by 2018 [4].

Early adolescent pregnancies have significant health consequences for both adolescent mothers and their neonates. Complications during pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death among girls aged 15 to 19 worldwide [5, 6]. Births to adolescent mothers account for 10% of births worldwide, but they make up 23% of maternal morbidity and mortality. 90% of these deaths occur in resource-poor countries, and the majority of them are preventable [1]. Studies have also shown that an adolescent pregnancy can lead to an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, low birth weight, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, miscarriage, premature birth, postpartum endometritis, systemic infection, and neonatal complications [7, 8].

Adolescent pregnancy is a global concern due to the high rate of unsafe abortions, lack of knowledge-seeking behaviors, inadequate prenatal care, and lack of support [1]. It is necessary to improve access to appropriate prenatal care to reduce adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes [9]. Raatikainen et al. showed that when perinatal care is conducted properly, maternal age alone does not play a significant role in adverse pregnancy outcomes [10].

Unfortunately, the attendance of adolescents in antenatal classes and antenatal visits during the first trimester is significantly lower than that of adult women [1]. Reasons for delays in seeking care are multifactorial. They include a lack of knowledge about the importance of prenatal care and an understanding of the consequences of not receiving it, a desire to conceal the pregnancy, thoughts about abortion, concerns about privacy or judgmental attitudes from healthcare providers or adults, and financial barriers [1].

Comprehensive, multidisciplinary, adolescent-centered care is considered the gold standard for managing the various issues associated with adolescent pregnancy. The primary goal is to improve outcomes for both mothers and their infants. Providing prenatal care that specifically focuses on adolescents has been shown to result in better outcomes compared to standard prenatal care. This includes a decrease in preterm birth, low birth weight, and significant cost savings in infant and child health expenses related to premature birth [11-13].

Considering that teenage mothers are one of the high-risk groups of women in society and that effective care can prevent or reduce the adverse consequences of pregnancy to some extent, finding a suitable approach for effective care is particularly important. Therefore, a systematic review study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of prenatal clinics for adolescents in improving birth outcomes.

Information and Methods

Study design

This study was a systematic review, adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines. This approach ensures that the study is reported with transparency and rigor [14].

Search strategy

In order to find the relevant articles, some keywords were identified to search for. These search terms were identified in relevant articles and through a MeSH search in PubMed. Subsequently, the search strategy was established. Following this, databases were chosen according to the Cochrane Systematic Review Handbook guidelines. At least three primary databases and one sub-database were selected for the search, with PubMed, Scopus, and ISI being the primary databases, and the Cochrane Library being chosen as the sub-database. To assess gray literature, encompassing conference article summaries, theses or master's theses, and research project findings, various methods were employed. These methods involved exploring the conference website, searching the proceeding section of the ISI database, and utilizing Google Scholar. The study involved a comprehensive examination of articles written in English. Searches were conducted on university websites and central libraries. Additionally, to ensure the inclusion of relevant data, the references to the identified articles were scrutinized after an initial evaluation of the abstract. The search period spanned from January 1, 1990 to December 31, 2022. To search for articles, the keywords “adolescent,” “teenage,” “pregnancy,” “antenatal visits,” “programs,” and “interventions” were used in various combinations (Table 1).

Table 1. Search strategy in PubMed

Study selection

All evaluated articles were inserted into Endnote X8 through electronic databases and manual searches. Two independent reviewers conducted a screening of the titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved to identify studies that could potentially be relevant. The full texts of the selected articles were then evaluated for eligibility based on pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population: Teenage pregnant women (ages 10 to 19)

Prenatal interventions: Pre-pregnancy interventions, evaluation of standard care, women with low-risk pregnancies, and studies with insufficient data or limited access to full-text articles.

Comparison group: Standard or usual care prenatal interventions.

Study design: Clinical trial (randomized/non-randomized) and cohort (retrospective-prospective) with at least one intervention and one comparison group.

Outcome study: the study aimed to investigate maternal-neonatal outcomes including premature birth (less than 37 weeks of pregnancy), low birth weight (at least 2500 grams), macrosomia (more than 4500 grams), stillbirth, and premature infant death. (less than 28 days), labor lasting less than 7 minutes, hospitalization in the special care unit, breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, shoulder dystocia, cesarean delivery with and without labor, instrumental delivery, hospitalization of the mother in the special care unit, length of stay in the hospital, postpartum bleeding, and 3rd and 4th-degree tears).

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers performed data extraction using a standardized form. The extracted information from each study included study characteristics (author, year of publication), randomization, blindness, characteristics of participants, details of intervention, control or comparison, outcomes assessed, tools, and findings.

Assessment of the risk of bias

The internal validity of articles was assessed using the "Graphical Assessment Tool for Epidemiological Studies" (GATE) developed by Jackson et al. GATE is a general quality assessment tool that can be applied to a wide range of experimental and observational study designs [15].

Criteria used in GATE

The following Rambo acronym was used for the critical evaluation process.

1. Representativeness (reference population): This refers to whether the participants in the study are truly representative of the populations in foreign countries.

2. Allocation or adjustment: The random sequence and its allocation, as well as the use of adjustment methods to eliminate bias, must be clearly explained.

3. Accounted for: All study participants must be accounted for in the analysis (using ITT treatment intention analysis) and reasons for dropouts must be disclosed.

The measures of results should ideally be blind or objective. This way, Rambo can determine if there are any flaws in the validity of the study being evaluated.

If Rambo indicates that the study was conducted in a way that lacks validity in certain aspects, then a judgment must be made about the overall validity of the study.

To do this, we needed to assess the potential impact of each flaw in the study and how it may affect the results, to determine if the cumulative impact of these flaws is likely to result in a significant change in the overall estimate of the study's impact.

Based on these criteria, studies will be classified into three general categories: (++) Good: Well reported and reliable, (+) Mixed: There were some weaknesses but not enough to significantly impact the study's usefulness, and (-) Poor: The study was not reliable, and not useful. The exclusion criteria included lack of access to the full text of the article, non-English language articles, protocol articles, and guideline reports.

Findings

Study selection

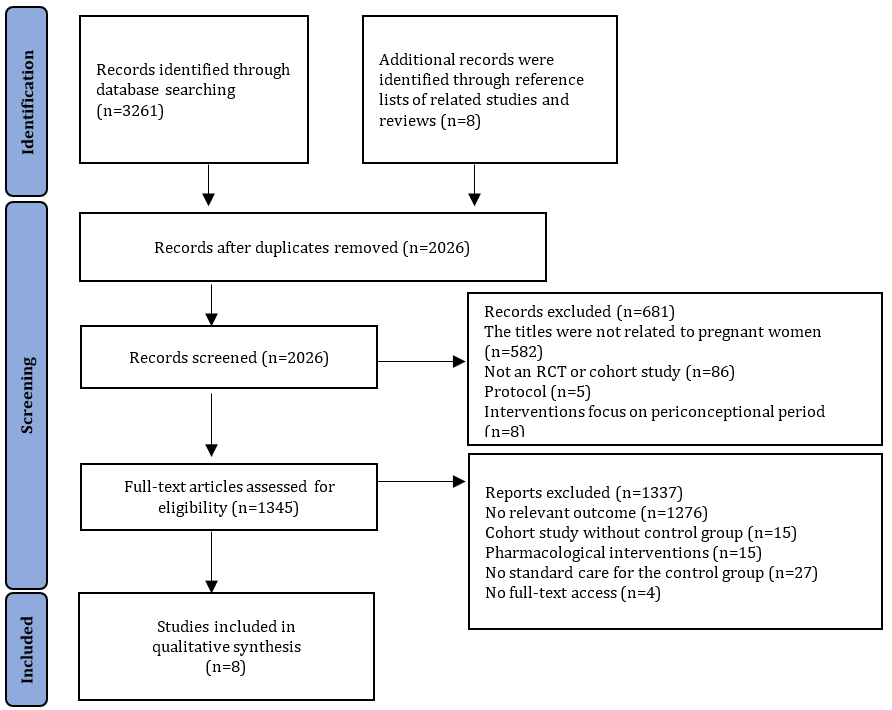

In this review, 8 out of 3261 studies found in the database were selected to be included in the study. These articles were remained after removing duplicates and screening studies based on inclusion criteria. Eight cohort studies (retrospective, prospective and combined) were included in the systematic review of prenatal interventions. The most common reason for exclusion was that the reported intervention was not specific to adolescents (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The PRISMA flow diagram of studies included and excluded in each review

Included study characteristics

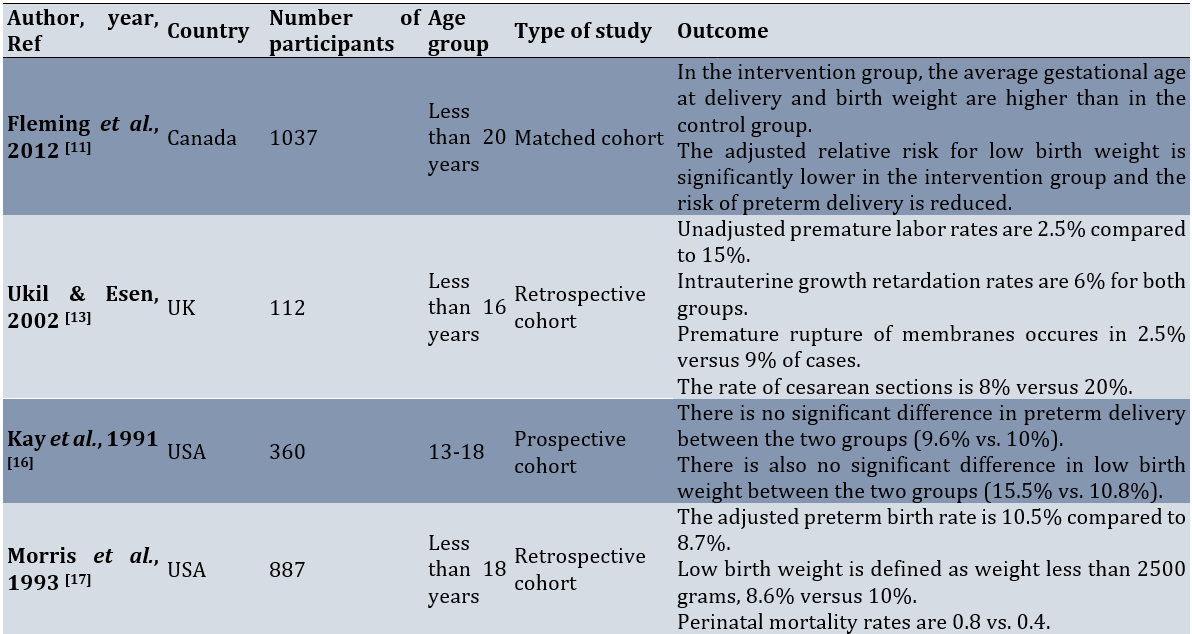

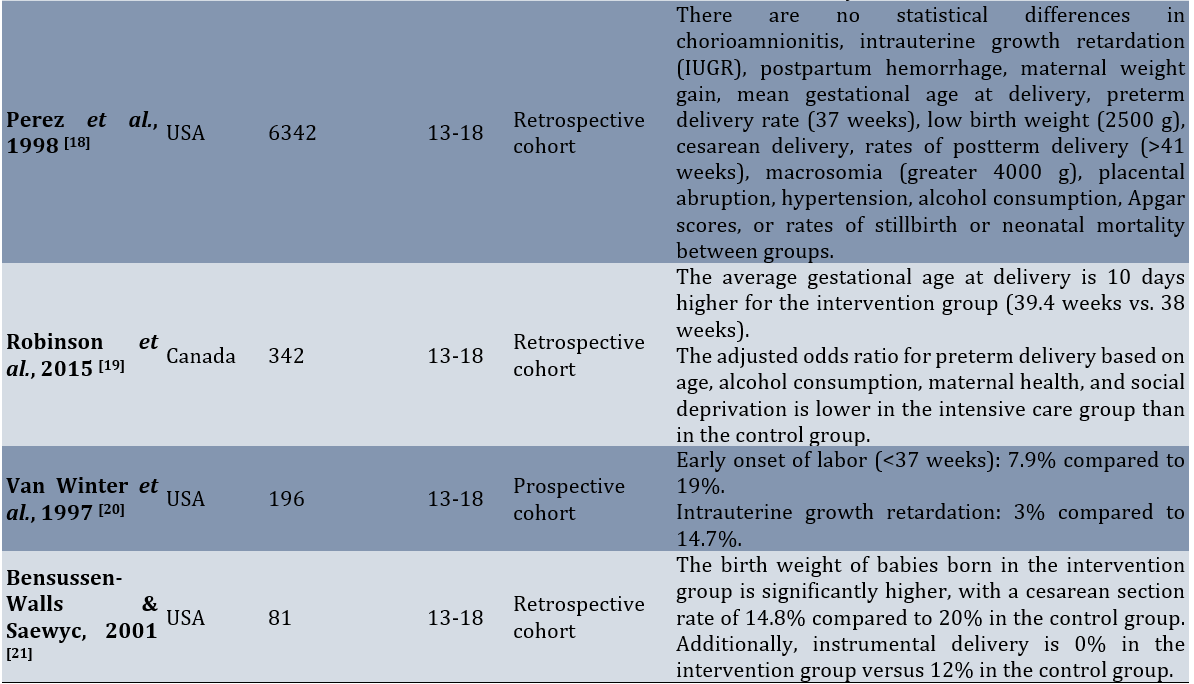

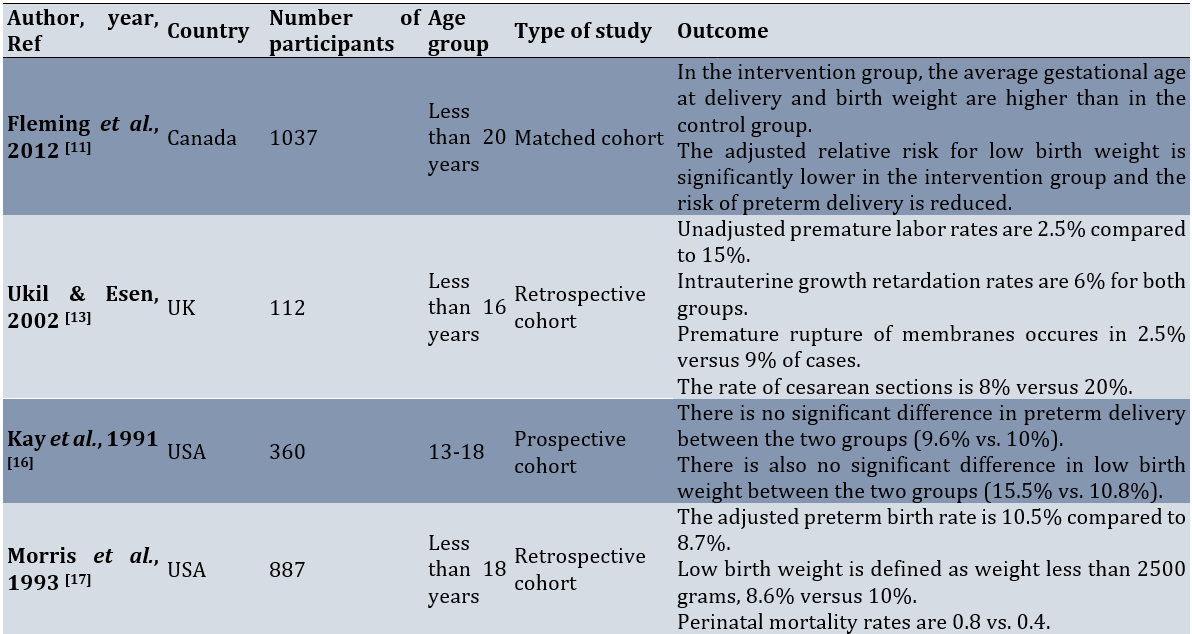

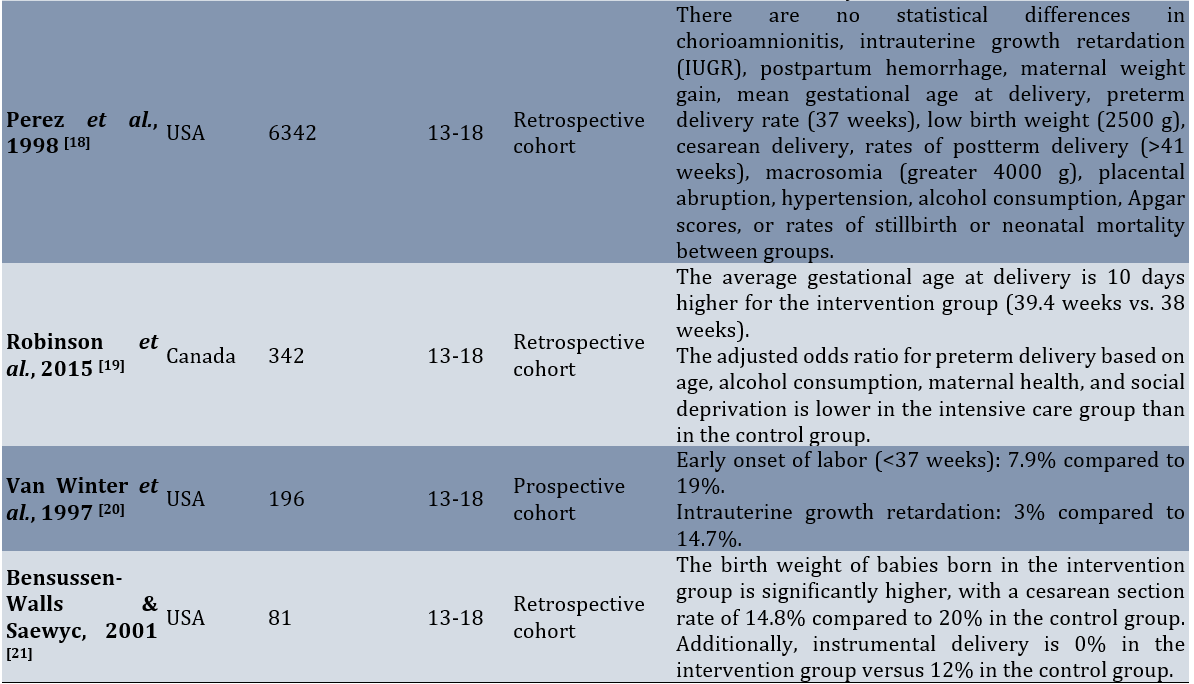

Among the studies included in this systematic review, 5 studies were conducted in America, 2 in Canada, and 1 in England. Adolescents in the included studies were predominantly single, experiencing their first pregnancy, and were described as having a low socioeconomic status (Table 2). These clinics offered a range of services, including education, nutrition counseling, and medical care to adolescents in various settings, such as hospitals, schools, or communities. The control group in all selected studies received standard or usual care. The assessment of the risk of bias was poor in all 8 selected studies.

Table 2. Studies included in the systematic review

All studies had a control group, except the Bensussen‐Walls & Saewyc [21] study, which had two control groups (usual care and group prenatal care). The study was deemed to be of poor quality.

Effect of adolescent-specific prenatal clinics on birth outcomes

Preterm birth

Seven studies (Robinson et al. [19]; Fleming et al. [11]; Ukil & Esen [13]; Perez et al. [18]; Van Winter et al. [20]; Morris et al. [17]; Kay et al. [16]) examined preterm birth as an outcome. Four of these studies (Robinson et al. [19]; Fleming et al. [11]; Ukil & Esen [13]; Van Winter et al. [20]) conclude that clinics were effective in reducing preterm births, while three studies (Perez et al. [18]; Morris et al. [17]; Kay et al. [16]) find out that the intervention is not effective in reducing preterm births.

Low birth weight

Three studies (Fleming et al. [11]; Morris et al. [17]; Kay et al. [16]) report low birth weight (defined as a weight less than 2500 g) as an outcome. Two of them (Fleming et al.; Morris et al.) find out that the intervention is effective in reducing low birth weight, while one study (Kay et al.) reports it as ineffective.

Perinatal mortality

Only two studies (Perez et al. [18]; Morris et al. [17]) report perinatal mortality as an outcome, and in these two studies, there is no significant difference between the two intervention and control groups in terms of perinatal mortality.

Intrauterine growth retardation

In two studies (Perez et al. [18]; Ukil & Esen [13]) intrauterine growth retardation is reported as an outcome. Both studies (Perez et al.; Ukil & Esen) do not report a significant difference in the rate of intrauterine growth retardation between the intervention and control groups.

Cesarean section

In three studies (Perez et al. [18]; Ukil & Esen [13]; Bensussen‐Walls & Saewyc [21]) cesarean section is reported as an outcome. The studies of Ukil & Esen and Bensussen‐Walls & Saewyc report a significant difference in the cesarean rate between the two groups, but in Perez et al.'s study, no significant difference is observed between the two groups.

Discussion

This systematic review was conducted to determine the effect of adolescent prenatal clinics on improving birth outcomes. Prenatal clinics for adolescents showed a small to moderate effect in reducing the rates of premature birth and low birth weight. Although the benefits observed in this review were relatively small, they should not be ignored. Compared to women of reproductive age, adolescents experience more frequent adverse pregnancy outcomes such as miscarriage and preterm birth [22, 23]. Preterm birth was estimated to cause approximately one million deaths per year [24]. Therefore, this review suggested that making changes to the content and location of prenatal care, compared to standard non-specialized services, can have long-term benefits for adolescents and their infants.

Some of the studies did not focus on pregnancy and delivery outcomes as the primary objective. Instead, they report them as a secondary outcome. This raises questions about whether these studies were adequately powered to detect improvements in pregnancy and delivery outcomes. On the other hand, there were additional concerns about the methodological quality of the studies included in this review. These concerns arose from the fact that all studies were observational and of poor methodological quality. Observational studies lack a good design to control the potential bias [25]. Therefore, the evaluation of specific interventions is considered to be weaker in comparison to trial interventions. Furthermore, most of the studies relied on the self-selection of prenatal care from specialty clinics compared to usual care, regardless of women's age. Potential differences affecting the outcome of adolescent antenatal care clinics when this is the only service available remain unknown.

In this review, there was no clear evidence of the effectiveness of interventions for adolescents living in low to middle-income countries, despite the high prevalence of adolescent pregnancies and the associated risks. WHO data highlight wide disparities in health outcomes for pregnant adolescents in low- and middle-income areas. 95% of births worldwide are to adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries [26].

It was encouraging to find some evidence in this systematic review, albeit limited, that antenatal clinics for adolescents could benefit women at a very vulnerable time in their lives. This support can have lifelong consequences for both the women themselves and the health of their babies. Financial problems, long waiting times to receive care, unfriendly behavior of staff, shyness, and the attempt of adolescents to hide their pregnancy are all known as obstacles for pregnant teenagers to attend non-age-specific prenatal clinics. The lack of timely care can be a factor for premature birth in this age group [27]. Adolescent clinics have implemented various approaches to address both real and perceived experiences. These approaches include offering programs outside of hospital settings, such as schools or community centers, with free access. These clinics aim to provide a less hostile environment with trained staff who are sensitive to the needs of adolescents, leading to non-hostile admissions. This type of environment may interfere less with other important aspects of their lives, such as education and social support. Additionally, cognitively, adolescents are still developing, and there are reported differences between adolescent and adult brains that affect attention, reward evaluation, and goal-directed behavior [28]. Therefore, health education components should be delivered in an age-appropriate manner by individuals who can establish trusting relationships with adolescents and take a more comprehensive approach to their care. This approach should include nutritional rehabilitation, psychological counseling, and early screening for infections [29].

This research also identified the need for more research in the area of prenatal care for teenage pregnant women. One limitation of this study is the limited number and low-quality of evidence, which means that the findings should be interpreted with caution. To obtain more definitive evidence on how to reduce adverse perinatal outcomes in adolescent pregnant women, it is necessary to design robust randomized clinical trial studies specifically focused on certain clinics.

A final consideration when interpreting the evidence presented in this review was that the search process and included studies were limited to English articles. Language limitations were a recognized problem, and we did not have the budget to review publications in other languages, which may include studies from low-income countries.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of adolescent-specific prenatal clinics in improving birth outcomes is uncertain.

Acknowledgments: The authors sincerely want to thank their colleagues who provided advice and knowledge that helped them significantly in writing the paper.

Ethical Permission: Nothing declared by the authors.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Mohammadi S (First Author), Main Researcher/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (35%); Pajohideh ZS (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/ Statistical Analyst (30%); Rabiei Z (Third Author), Main Researcher/Introduction Writer (35%)

Funding/Support: Nothing declared by the authors.

Adolescence is a distinct and unique stage of development in a woman's life. Consequently, diagnosing and managing pregnancy during this period requires identifying risk factors and understanding the necessary elements of care for successful outcomes for both mother and infant [1]. An adolescent pregnancy refers to a pregnancy that occurs between the ages of 10-19 years. The majority of adolescent pregnancies occur specifically between the ages of 15-19 years [2]. In 2018, the global adolescent birth rate was estimated at 44 births per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 [3]. The adolescent pregnancy rate in Iran in the 1960s was about 150 pregnancies per 1,000 adolescents, but it had decreased to 26 by 2018 [4].

Early adolescent pregnancies have significant health consequences for both adolescent mothers and their neonates. Complications during pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death among girls aged 15 to 19 worldwide [5, 6]. Births to adolescent mothers account for 10% of births worldwide, but they make up 23% of maternal morbidity and mortality. 90% of these deaths occur in resource-poor countries, and the majority of them are preventable [1]. Studies have also shown that an adolescent pregnancy can lead to an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, low birth weight, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, miscarriage, premature birth, postpartum endometritis, systemic infection, and neonatal complications [7, 8].

Adolescent pregnancy is a global concern due to the high rate of unsafe abortions, lack of knowledge-seeking behaviors, inadequate prenatal care, and lack of support [1]. It is necessary to improve access to appropriate prenatal care to reduce adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes [9]. Raatikainen et al. showed that when perinatal care is conducted properly, maternal age alone does not play a significant role in adverse pregnancy outcomes [10].

Unfortunately, the attendance of adolescents in antenatal classes and antenatal visits during the first trimester is significantly lower than that of adult women [1]. Reasons for delays in seeking care are multifactorial. They include a lack of knowledge about the importance of prenatal care and an understanding of the consequences of not receiving it, a desire to conceal the pregnancy, thoughts about abortion, concerns about privacy or judgmental attitudes from healthcare providers or adults, and financial barriers [1].

Comprehensive, multidisciplinary, adolescent-centered care is considered the gold standard for managing the various issues associated with adolescent pregnancy. The primary goal is to improve outcomes for both mothers and their infants. Providing prenatal care that specifically focuses on adolescents has been shown to result in better outcomes compared to standard prenatal care. This includes a decrease in preterm birth, low birth weight, and significant cost savings in infant and child health expenses related to premature birth [11-13].

Considering that teenage mothers are one of the high-risk groups of women in society and that effective care can prevent or reduce the adverse consequences of pregnancy to some extent, finding a suitable approach for effective care is particularly important. Therefore, a systematic review study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of prenatal clinics for adolescents in improving birth outcomes.

Information and Methods

Study design

This study was a systematic review, adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines. This approach ensures that the study is reported with transparency and rigor [14].

Search strategy

In order to find the relevant articles, some keywords were identified to search for. These search terms were identified in relevant articles and through a MeSH search in PubMed. Subsequently, the search strategy was established. Following this, databases were chosen according to the Cochrane Systematic Review Handbook guidelines. At least three primary databases and one sub-database were selected for the search, with PubMed, Scopus, and ISI being the primary databases, and the Cochrane Library being chosen as the sub-database. To assess gray literature, encompassing conference article summaries, theses or master's theses, and research project findings, various methods were employed. These methods involved exploring the conference website, searching the proceeding section of the ISI database, and utilizing Google Scholar. The study involved a comprehensive examination of articles written in English. Searches were conducted on university websites and central libraries. Additionally, to ensure the inclusion of relevant data, the references to the identified articles were scrutinized after an initial evaluation of the abstract. The search period spanned from January 1, 1990 to December 31, 2022. To search for articles, the keywords “adolescent,” “teenage,” “pregnancy,” “antenatal visits,” “programs,” and “interventions” were used in various combinations (Table 1).

Table 1. Search strategy in PubMed

Study selection

All evaluated articles were inserted into Endnote X8 through electronic databases and manual searches. Two independent reviewers conducted a screening of the titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved to identify studies that could potentially be relevant. The full texts of the selected articles were then evaluated for eligibility based on pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population: Teenage pregnant women (ages 10 to 19)

Prenatal interventions: Pre-pregnancy interventions, evaluation of standard care, women with low-risk pregnancies, and studies with insufficient data or limited access to full-text articles.

Comparison group: Standard or usual care prenatal interventions.

Study design: Clinical trial (randomized/non-randomized) and cohort (retrospective-prospective) with at least one intervention and one comparison group.

Outcome study: the study aimed to investigate maternal-neonatal outcomes including premature birth (less than 37 weeks of pregnancy), low birth weight (at least 2500 grams), macrosomia (more than 4500 grams), stillbirth, and premature infant death. (less than 28 days), labor lasting less than 7 minutes, hospitalization in the special care unit, breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, shoulder dystocia, cesarean delivery with and without labor, instrumental delivery, hospitalization of the mother in the special care unit, length of stay in the hospital, postpartum bleeding, and 3rd and 4th-degree tears).

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers performed data extraction using a standardized form. The extracted information from each study included study characteristics (author, year of publication), randomization, blindness, characteristics of participants, details of intervention, control or comparison, outcomes assessed, tools, and findings.

Assessment of the risk of bias

The internal validity of articles was assessed using the "Graphical Assessment Tool for Epidemiological Studies" (GATE) developed by Jackson et al. GATE is a general quality assessment tool that can be applied to a wide range of experimental and observational study designs [15].

Criteria used in GATE

The following Rambo acronym was used for the critical evaluation process.

1. Representativeness (reference population): This refers to whether the participants in the study are truly representative of the populations in foreign countries.

2. Allocation or adjustment: The random sequence and its allocation, as well as the use of adjustment methods to eliminate bias, must be clearly explained.

3. Accounted for: All study participants must be accounted for in the analysis (using ITT treatment intention analysis) and reasons for dropouts must be disclosed.

The measures of results should ideally be blind or objective. This way, Rambo can determine if there are any flaws in the validity of the study being evaluated.

If Rambo indicates that the study was conducted in a way that lacks validity in certain aspects, then a judgment must be made about the overall validity of the study.

To do this, we needed to assess the potential impact of each flaw in the study and how it may affect the results, to determine if the cumulative impact of these flaws is likely to result in a significant change in the overall estimate of the study's impact.

Based on these criteria, studies will be classified into three general categories: (++) Good: Well reported and reliable, (+) Mixed: There were some weaknesses but not enough to significantly impact the study's usefulness, and (-) Poor: The study was not reliable, and not useful. The exclusion criteria included lack of access to the full text of the article, non-English language articles, protocol articles, and guideline reports.

Findings

Study selection

In this review, 8 out of 3261 studies found in the database were selected to be included in the study. These articles were remained after removing duplicates and screening studies based on inclusion criteria. Eight cohort studies (retrospective, prospective and combined) were included in the systematic review of prenatal interventions. The most common reason for exclusion was that the reported intervention was not specific to adolescents (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The PRISMA flow diagram of studies included and excluded in each review

Included study characteristics

Among the studies included in this systematic review, 5 studies were conducted in America, 2 in Canada, and 1 in England. Adolescents in the included studies were predominantly single, experiencing their first pregnancy, and were described as having a low socioeconomic status (Table 2). These clinics offered a range of services, including education, nutrition counseling, and medical care to adolescents in various settings, such as hospitals, schools, or communities. The control group in all selected studies received standard or usual care. The assessment of the risk of bias was poor in all 8 selected studies.

Table 2. Studies included in the systematic review

All studies had a control group, except the Bensussen‐Walls & Saewyc [21] study, which had two control groups (usual care and group prenatal care). The study was deemed to be of poor quality.

Effect of adolescent-specific prenatal clinics on birth outcomes

Preterm birth

Seven studies (Robinson et al. [19]; Fleming et al. [11]; Ukil & Esen [13]; Perez et al. [18]; Van Winter et al. [20]; Morris et al. [17]; Kay et al. [16]) examined preterm birth as an outcome. Four of these studies (Robinson et al. [19]; Fleming et al. [11]; Ukil & Esen [13]; Van Winter et al. [20]) conclude that clinics were effective in reducing preterm births, while three studies (Perez et al. [18]; Morris et al. [17]; Kay et al. [16]) find out that the intervention is not effective in reducing preterm births.

Low birth weight

Three studies (Fleming et al. [11]; Morris et al. [17]; Kay et al. [16]) report low birth weight (defined as a weight less than 2500 g) as an outcome. Two of them (Fleming et al.; Morris et al.) find out that the intervention is effective in reducing low birth weight, while one study (Kay et al.) reports it as ineffective.

Perinatal mortality

Only two studies (Perez et al. [18]; Morris et al. [17]) report perinatal mortality as an outcome, and in these two studies, there is no significant difference between the two intervention and control groups in terms of perinatal mortality.

Intrauterine growth retardation

In two studies (Perez et al. [18]; Ukil & Esen [13]) intrauterine growth retardation is reported as an outcome. Both studies (Perez et al.; Ukil & Esen) do not report a significant difference in the rate of intrauterine growth retardation between the intervention and control groups.

Cesarean section

In three studies (Perez et al. [18]; Ukil & Esen [13]; Bensussen‐Walls & Saewyc [21]) cesarean section is reported as an outcome. The studies of Ukil & Esen and Bensussen‐Walls & Saewyc report a significant difference in the cesarean rate between the two groups, but in Perez et al.'s study, no significant difference is observed between the two groups.

Discussion

This systematic review was conducted to determine the effect of adolescent prenatal clinics on improving birth outcomes. Prenatal clinics for adolescents showed a small to moderate effect in reducing the rates of premature birth and low birth weight. Although the benefits observed in this review were relatively small, they should not be ignored. Compared to women of reproductive age, adolescents experience more frequent adverse pregnancy outcomes such as miscarriage and preterm birth [22, 23]. Preterm birth was estimated to cause approximately one million deaths per year [24]. Therefore, this review suggested that making changes to the content and location of prenatal care, compared to standard non-specialized services, can have long-term benefits for adolescents and their infants.

Some of the studies did not focus on pregnancy and delivery outcomes as the primary objective. Instead, they report them as a secondary outcome. This raises questions about whether these studies were adequately powered to detect improvements in pregnancy and delivery outcomes. On the other hand, there were additional concerns about the methodological quality of the studies included in this review. These concerns arose from the fact that all studies were observational and of poor methodological quality. Observational studies lack a good design to control the potential bias [25]. Therefore, the evaluation of specific interventions is considered to be weaker in comparison to trial interventions. Furthermore, most of the studies relied on the self-selection of prenatal care from specialty clinics compared to usual care, regardless of women's age. Potential differences affecting the outcome of adolescent antenatal care clinics when this is the only service available remain unknown.

In this review, there was no clear evidence of the effectiveness of interventions for adolescents living in low to middle-income countries, despite the high prevalence of adolescent pregnancies and the associated risks. WHO data highlight wide disparities in health outcomes for pregnant adolescents in low- and middle-income areas. 95% of births worldwide are to adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries [26].

It was encouraging to find some evidence in this systematic review, albeit limited, that antenatal clinics for adolescents could benefit women at a very vulnerable time in their lives. This support can have lifelong consequences for both the women themselves and the health of their babies. Financial problems, long waiting times to receive care, unfriendly behavior of staff, shyness, and the attempt of adolescents to hide their pregnancy are all known as obstacles for pregnant teenagers to attend non-age-specific prenatal clinics. The lack of timely care can be a factor for premature birth in this age group [27]. Adolescent clinics have implemented various approaches to address both real and perceived experiences. These approaches include offering programs outside of hospital settings, such as schools or community centers, with free access. These clinics aim to provide a less hostile environment with trained staff who are sensitive to the needs of adolescents, leading to non-hostile admissions. This type of environment may interfere less with other important aspects of their lives, such as education and social support. Additionally, cognitively, adolescents are still developing, and there are reported differences between adolescent and adult brains that affect attention, reward evaluation, and goal-directed behavior [28]. Therefore, health education components should be delivered in an age-appropriate manner by individuals who can establish trusting relationships with adolescents and take a more comprehensive approach to their care. This approach should include nutritional rehabilitation, psychological counseling, and early screening for infections [29].

This research also identified the need for more research in the area of prenatal care for teenage pregnant women. One limitation of this study is the limited number and low-quality of evidence, which means that the findings should be interpreted with caution. To obtain more definitive evidence on how to reduce adverse perinatal outcomes in adolescent pregnant women, it is necessary to design robust randomized clinical trial studies specifically focused on certain clinics.

A final consideration when interpreting the evidence presented in this review was that the search process and included studies were limited to English articles. Language limitations were a recognized problem, and we did not have the budget to review publications in other languages, which may include studies from low-income countries.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of adolescent-specific prenatal clinics in improving birth outcomes is uncertain.

Acknowledgments: The authors sincerely want to thank their colleagues who provided advice and knowledge that helped them significantly in writing the paper.

Ethical Permission: Nothing declared by the authors.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Mohammadi S (First Author), Main Researcher/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (35%); Pajohideh ZS (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/ Statistical Analyst (30%); Rabiei Z (Third Author), Main Researcher/Introduction Writer (35%)

Funding/Support: Nothing declared by the authors.

Keywords:

Prenatal Care [MeSH], Special Clinic [MeSH], Adolescents [MeSH], Birth Outcomes [MeSH], Systematic Review [MeSH]

References

1. Fleming N, O'Driscoll T, Becker G, Spitzer RF, Canpago Committee. Adolescent pregnancy guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(8):740-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30180-8]

2. Molina RC, Roca CG, Zamorano JS, Araya EG. Family planning and adolescent pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;24(2):209-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.09.008]

3. De Vargas Nunes Coll C, Ewerling F, Hellwig F, De Barros AJD. Contraception in adolescence: The influence of parity and marital status on contraceptive use in 73 low-and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):21. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12978-019-0686-9]

4. Leftwich HK, Alves MVO. Adolescent pregnancy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017;64(2):381-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.11.007]

5. Karataşlı V, Kanmaz AG, İnan AH, Budak A, Beyan E. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of adolescent pregnancy. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48(5):347-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jogoh.2019.02.011]

6. Maheshwari MV, Khalid N, Patel PD, Alghareeb R, Hussain A. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of adolescent pregnancy: A narrative review. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e25921. [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.25921]

7. Amjad S, MacDonald I, Chambers T, Osornio‐Vargas A, Chandra S, Voaklander D, et al. Social determinants of health and adverse maternal and birth outcomes in adolescent pregnancies: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):88-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/ppe.12529]

8. Xie Y, Harville EW, Madkour AS. Academic performance, educational aspiration and birth outcomes among adolescent mothers: A national longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:3. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-14-3]

9. Phupong V, Suebnukarn K. Obstetric outcomes in nulliparous young adolescents. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38(1):141-5. [Link]

10. Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Verkasalo PK, Heinonen S. Good outcome of teenage pregnancies in high-quality maternity care. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(2):157-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/cki158]

11. Fleming NA, Tu X, Black AY. Improved obstetrical outcomes for adolescents in a community-based outreach program: A matched cohort study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34(12):1134-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35460-3]

12. Quinlivan JA, Evans SF. Teenage antenatal clinics may reduce the rate of preterm birth: A prospective study. BJOG. 2004;111(6):571-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00146.x]

13. Ukil D, Esen UI. Early teenage pregnancy outcome: A comparison between a standard and a dedicated teenage antenatal clinic. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(3):270-2. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/01443610220130544]

14. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.n71]

15. Jackson R, Ameratunga S, Broad J, Connor J, Lethaby A, Robb G, et al. The GATE frame: Critical appraisal with pictures. Evid Based Med. 2006;11(2):35-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/ebm.11.2.35]

16. Kay BJ, Share DA, Jones K, Smith M, Garcia D, Yeo SA. Process, costs, and outcomes of community-based prenatal care for adolescents. Med Care. 1991;29(6):531-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00005650-199106000-00012]

17. Morris DL, Berenson AB, Lawson J, Wiemann CM. Comparison of adolescent pregnancy outcomes by prenatal care source. J Reprod Med. 1993;38(5):375-80. [Link]

18. Perez R, Patience T, Pulous E, Brown G, McEwen A, Asato A, et al. Use of a focussed teen prenatal clinic at a military teaching hospital: Model for improved outcomes of unmarried mothers. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;38(3):280-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1998.tb03066.x]

19. Robinson A, O'Donohue M, Drolet J, Di Meglio G. 123. Tackling teenage pregnancy together: The effect of a multidisciplinary approach on adolescent obstetrical outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):S64-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.128]

20. Van Winter J, Harmon M, Atkinson E, Simmons P, Ogburn Jr PL. Young moms' clinic: A multidisciplinary approach to pregnancy education in teens and in young single women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10(1):28-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1083-3188(97)70041-X]

21. Bensussen‐Walls W, Saewyc EM. Teen‐focused care versus adult‐focused care for the high‐risk pregnant adolescent: An outcomes evaluation. Public Health Nurs. 2001;18(6):424-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00424.x]

22. Malek ME, Borghei NS, Mehrbakhsh Z. Comparison of the outcomes of pregnancy and childbirth in married adolescents and young women. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2023;26(3):78-89. [Persian] [Link]

23. Marvin-Dowle K, Soltani H. A comparison of neonatal outcomes between adolescent and adult mothers in developed countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X. 2020;6:100109. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.eurox.2020.100109]

24. Walani SR. Global burden of preterm birth. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;150(1):31-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ijgo.13195]

25. Kotsakis GA. Minimizing risk of bias in clinical implant research study design. Periodontol 2000. 2019;81(1):18-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/prd.12279]

26. Huda MM, O'Flaherty M, Finlay JE, Al Mamun A. Time trends and sociodemographic inequalities in the prevalence of adolescent motherhood in 74 low-income and middle-income countries: A population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(1):26-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30311-4]

27. Gadson A, Akpovi E, Mehta PK. Exploring the social determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care utilization and maternal outcome. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(5):308-17. [Link] [DOI:10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.008]

28. Van Den Heuvel MW, Stikkelbroek YA, Bodden DH, Van Baar AL. Coping with stressful life events: Cognitive emotion regulation profiles and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. 2020;32(3):985-95. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0954579419000920]

29. WHO. WHO recommendations on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Link]