Volume 5, Issue 3 (2024)

J Clinic Care Skill 2024, 5(3): 125-135 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/06/29 | Accepted: 2024/08/18 | Published: 2024/09/26

Received: 2024/06/29 | Accepted: 2024/08/18 | Published: 2024/09/26

How to cite this article

Goudarzi F, Hekmatzadeh S. Herbal Products in Cesarean Wound Healing. J Clinic Care Skill 2024; 5 (3) :125-135

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-283-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-283-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Medicinal Plant Research Center, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (4608 Views)

Introduction

Despite the global emphasis on promoting physiological delivery, cesarean section remains one of the most common surgeries worldwide [1]. The prevalence of cesarean sections varies among different countries, ranging from 20% in France to 60% in some regions of Latin America [2]. The prevalence of cesarean sections is also high in Iran. According to the World Health Organization, the rate of cesarean sections in Iran in 2018 was 45.85% [3]. With the increase in the cesarean section rate, its side effects, such as hematoma, infection of the surgical site, wound dehiscence, and pain, also increase [4].

Complications resulting from cesarean wounds can occur in 2.5% to 34% of cesarean cases. One of the most significant complications of cesarean wounds is improper repair, which can lead to wound infection [5]. Wound infection, hematoma, and wound dehiscence are among the most common complications of cesarean section, leading to the mother’s re-hospitalization and frequent visits to the doctor, which can impose an economic burden on both the family and society [6]. Pain caused by the cesarean section wound can weaken the immune system, increase oxygen consumption by the myocardium, and lead to hypoglycemia, which causes delays in wound healing, as well as disturbances in bowel movements and decreased respiratory function [7]. In addition to the recovery period after surgery, women who undergo cesarean sections are also experiencing the postpartum period. In other words, in addition to managing the complications and inconveniences related to the cesarean section, they must also be able to breastfeed and care for their babies, thereby requiring additional support [8]. However, the scar and pain caused by cesarean section can interfere with the mother’s proper positioning for breastfeeding [9]. Therefore, pain management and the acceleration of wound healing after cesarean section are critical components of mother and baby care protocols and breastfeeding [10].

Wound healing involves coordinated repair responses that begin after surgery or trauma and lead to tissue regeneration. These responses are closely related to pre-operative and post-operative treatments, as well as trauma management. The healing process for all wounds occurs gradually and includes three stages: the inflammatory phase, the proliferation phase, and the maturation phase [11]. For the management of surgical wounds, including cesarean sections, there is a need for a comprehensive program aimed at care, proper wound repair in the shortest time possible, prevention of complications such as infection, wound dehiscence, improper scar formation, pain reduction, and facilitating the individual’s return to normal life [12]. Despite numerous investigations, no standard method has been established for the management of surgical wounds. However, some medications, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and narcotic analgesics, are used to manage pain and accelerate the healing of cesarean wounds. These medications are associated with side effects, such as nausea, respiratory discomfort, gastrointestinal bleeding, and itching [10]. In addition to being costly, many drugs available for wound management can cause issues such as allergies and drug resistance [13].

Due to the limited success of existing treatment methods, researchers are increasingly inclined to explore complementary medicine [14]. Consequently, the use of complementary medicine, including herbal therapy, is on the rise for managing pain and accelerating the healing of cesarean section wounds [15]. Traditional healers have been recommending the local use of certain plants to heal wounds caused by injuries and burns to their patients for many years. In general, medicinal plants for wound healing are cost-effective, affordable, and safe [13]. On the other hand, given the special considerations regarding breastfeeding, studies have reported that mothers are reluctant to use chemical drugs during this period due to concerns about the drugs being secreted in breast milk and their potential effects on the baby. Therefore, the use of medicinal plants during this time is more favorable among mothers [16].

The World Health Organization also reported that 80% of the world’s population uses medicinal plants as part of their treatment during breastfeeding [17]. Overall, herbal medicines with anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects are promising candidates for wound healing [18]. The anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties of plants can create an environment free of bacteria and germs, as well as provide a balanced environment in terms of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, which can be effective in accelerating the wound healing process [19, 20]. Some plants, such as flax (Linum usitatissimum) [21], grape seed [18], Aloe vera [22], calendula (Calendula officinalis) [23], Hypericum perforatum [24], turmeric (Curcuma longa) [25, 26], and olive (Olea europaea), are effective in cesarean wound healing [14]. However, the results remain limited and non-clinical. Considering that traditional medicine has long been used in Iran and that there is an increasing demand for medicinal plants, and given that no study has assessed the effects of medicinal plants on wound healing, especially cesarean section wounds, in Iran, the present study aimed to systematically review the effectiveness of herbal products examined in clinical trials for the healing of cesarean section wounds. The results can be applied in clinical settings.

Information and Methods

This review study was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Search strategy

Clinical trials examining the effectiveness of herbal compounds in the treatment and acceleration of cesarean wound healing were searched in both English and Persian databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Scopus, Magiran, SID, and Iranmedex, with no time limit until April 2024. Keywords, including “cesarean section,” “wound healing,” “herbal medicine,” “complementary medicine,” and “alternative care,” available on MeSH, were used for the search. Additionally, AND and OR operators were employed in the search.

Inclusion criteria included clinical trials, the prescription of herbal products for cesarean wound healing, and studies published in Persian and English databases. Exclusion criteria consisted of a lack of access to the full text of articles, letters to the editor, commentaries, articles presented at conferences, preprinted articles, retracted articles, theses, protocols, review articles, and trials involving non-plant products.

Selection of articles

Out of 471 articles obtained from the initial search and five articles sourced from other means, 453 articles remained after removing duplicates. Following a review of the titles and abstracts, 94 articles were screened for full text, and ultimately, eight articles met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). All obtained articles were checked using EndNote version 21 for duplicate detection. Subsequently, the titles and abstracts were reviewed, followed by a full review of the articles in the second stage, conducted separately by two researchers. Finally, the articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two authors.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study selection process

Data extraction

Initially, a file for data extraction was designed by the authors. Then, the two authors individually reviewed the entered articles based on the prepared file and extracted the relevant data. The items in the prepared file included the characteristics of the research, such as the first author, year of publication, purpose of the study, study design, number of samples, intervention and control groups, type of intervention, method of measuring the results, duration of the investigation, and the results available in the CONSORT checklist. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two researchers, after which the content was evaluated for quality.

Quality assessment of the articles

The quality of the articles was evaluated using the CONSORT 2018 checklist [27], which consists of 45 items assessing seven aspects, including title, abstract, introduction, methods and findings, discussion, and other relevant sections. The selected articles received a score of one for each desired item present in each section and a score of zero if that item was absent. The overall quality score of each article was calculated based on the total number of items in the CONSORT checklist; thus, the highest possible score is 45, while the lowest score is zero.

Findings

Characteristics of the studies

Eight studies were evaluated with their publication dates ranging from 2010 to 2024. The articles originated from Iran (87.5%) [14, 18, 22-25, 28] and India (12.5%) [26], with a total sample size of 699 individuals. All clinical trials were randomized. In the studies, the healing process was assessed using the REEDA scale over eight to fourteen days. In five articles, the herbal product used was prepared in the form of a cream [14, 18, 21, 23, 24], which was applied twice a day to the wound area. In one study, the product was utilized as a dressing [22], and applied once within the first 24 hours after cesarean section. In two articles, the herbal product was prepared as a gel [25, 26].

The quality of the articles evaluated by the CONSORT tool was between 22 and 24, which indicates the average quality of the articles. Due to the small number of clinical trial studies in this field, it was not possible to assess the risk of publication bias.

The herbal product used to accelerate the cesarean wound healing

The plants examined in this review included flax (L. usitatissimum), grape seed, Aloe vera, calendula (C. officinalis), H. perforatum, turmeric (C. longa), and olive. Their derived products were applied topically in the form of ointments and gels.

L. usitatissimum

L. usitatissimum (flax) as an ointment was studied in a double-blind clinical trial conducted in 2019 for the management of cesarean wounds involving 120 women eligible for cesarean delivery at Imam Reza and Shahid Hashemi Hospitals in Mashhad. To evaluate wound healing, the REEDA scale was used on the first, fourth, and eighth days after the intervention. This scale assesses redness, edema, bruising, discharge, and the distance between the two edges of the wound, and it is completed through examination and observation. Each parameter on this scale is scored from zero to three. The mothers in both the flax and placebo groups were instructed to apply the ointment twice a day after washing and drying the sutures. They were advised to apply a finger-sized amount of the medication to the wound until a thin layer covered the entire area, allowing this layer to dry in the air, and to continue the treatment for eight days. There was a statistically significant difference between the intervention and placebo groups, as well as between the flax and control groups, in terms of cesarean wound healing at four and eight days post-intervention. Additionally, the Friedman test indicated significant differences in the changes in the REEDA scale across all three groups on different days (p<0.0001). During the study, none of the mothers reported any side effects [28].

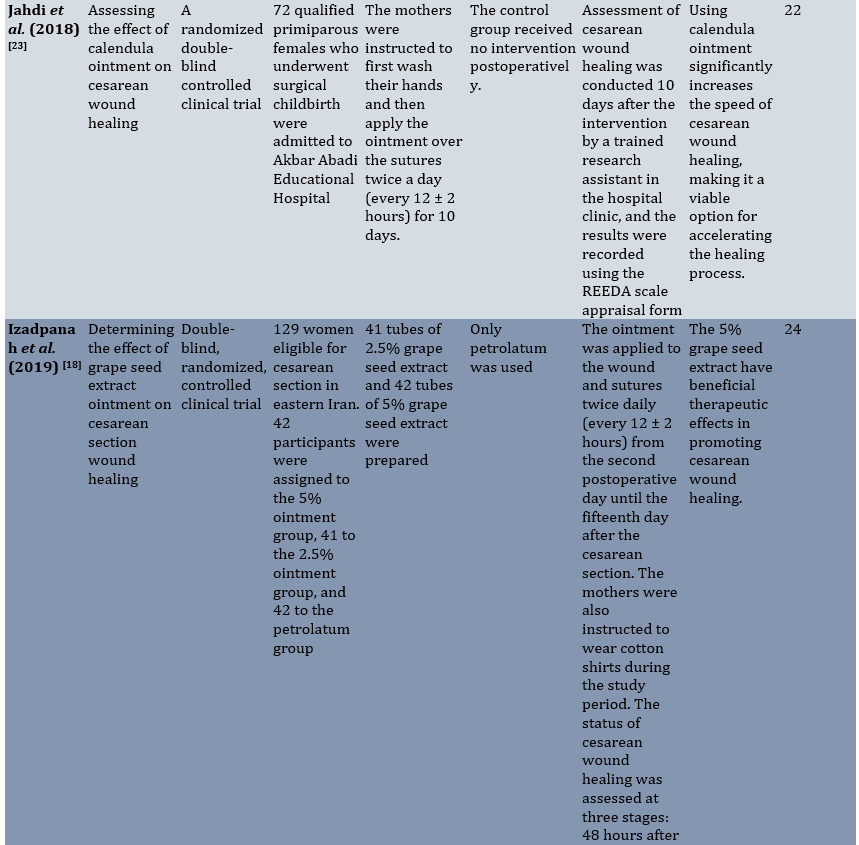

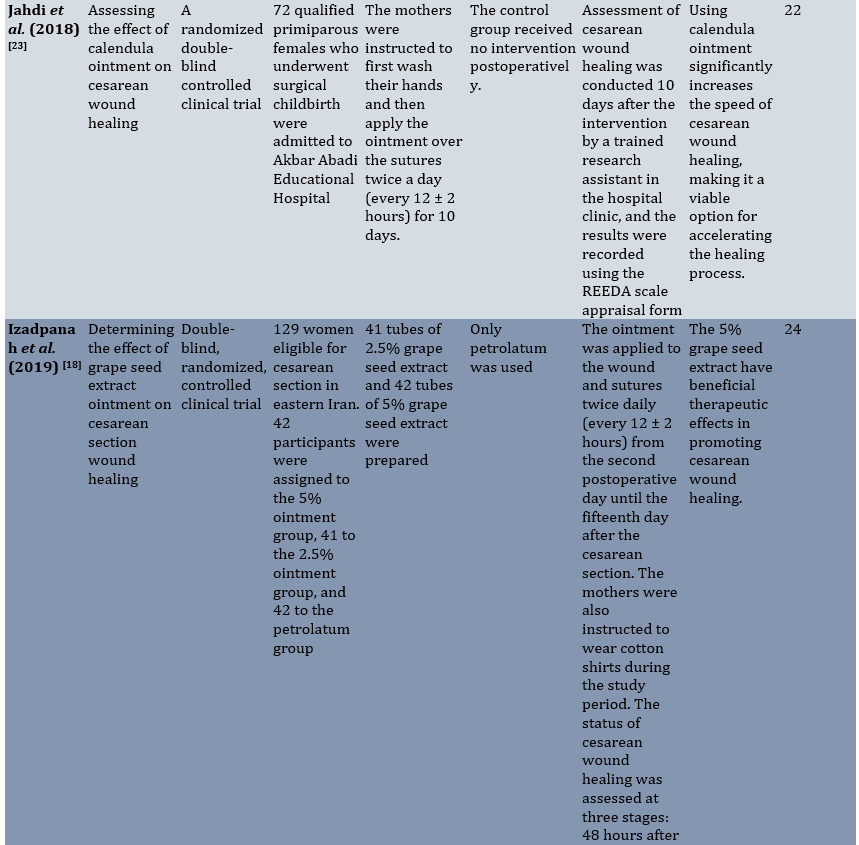

Grape seed

A double-blind clinical trial investigated the effect of grape seed extract as an ointment in 2019 on cesarean wound healing. In this study, 129 mothers were randomly divided into three groups; one group received a product containing 2.5% grape seed extract, another group received 5% extract, and the third group received Vaseline. There were 42 participants in the 5% group, 41 participants in the 2.5% group, and 42 participants in the Vaseline group. All three groups applied the ointments topically starting from the second day post-cesarean for 15 days, twice a day, according to the provided instructions. The groups were then evaluated for wound healing before the intervention, as well as on the 6th and 14th days after cesarean section, using the REEDA scale. On the sixth day of the intervention, there was no significant difference in the average scores of redness and discharge among the three groups. However, the average scores of edema, ecchymosis, and approximation were statistically significantly different across the groups. By the 14th day after the intervention, the three groups exhibited statistically significant differences in the average scores of redness, edema, ecchymosis, and approximation. The mean total scores of the REEDA scale were significantly different between the 5% ointment and 2.5% ointment groups, as well as between the 5% ointment and Vaseline groups on both the 6th and 14th days after the intervention. However, the mean total scores did not show a significant difference between the 2.5% ointment and Vaseline groups six days after the intervention. It was concluded that 5% grape seed extract may have beneficial therapeutic effects on cesarean section wound healing [18].

Aloe vera

A double-blind clinical trial investigated the effect of Aloe vera on cesarean section wounds in 2015, involving 90 participants who were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups (45 participants per group). Both groups received diclofenac suppositories and cefazolin ampoules. In the intervention group, the wound was bandaged with Aloe vera gel, while the control group received a simple dressing (dry gauze). The REEDA scale was used to evaluate both groups, with scores ranging from 0 to 15, where a higher score indicated poorer healing. Wound healing was assessed 24 hours after surgery and continued until eight days post-surgery. There was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of the wound healing score 24 hours after the operation (P=0.003). On the 8th day of the study, the total REEDA scale score was lower in the intervention group, although this difference was not statistically significant [22].

C. officinalis

A double-blind clinical trial assessed the effect of C. officinalis on cesarean wound healing in 2018, involving 72 participants who were randomly divided into intervention and control groups. The intervention group applied a 2% marigold hydroalcoholic ointment twice a day for ten days, while the control group did not use any ointment. Both groups were evaluated before the intervention and on days three, six, and nine after cesarean section based on the REEDA scale. The REEDA scale score ranged from 0 to 15, with a higher score indicating poorer healing. In the C. officinalis group, lower scores were observed on the third, sixth, and ninth days after treatment in both the total score and the five criteria of the REEDA scale, which included redness, edema, discharge, ecchymosis, and approximation of the wound edges. Statistically, there was a significant difference in wound healing between the intervention and control groups [23].

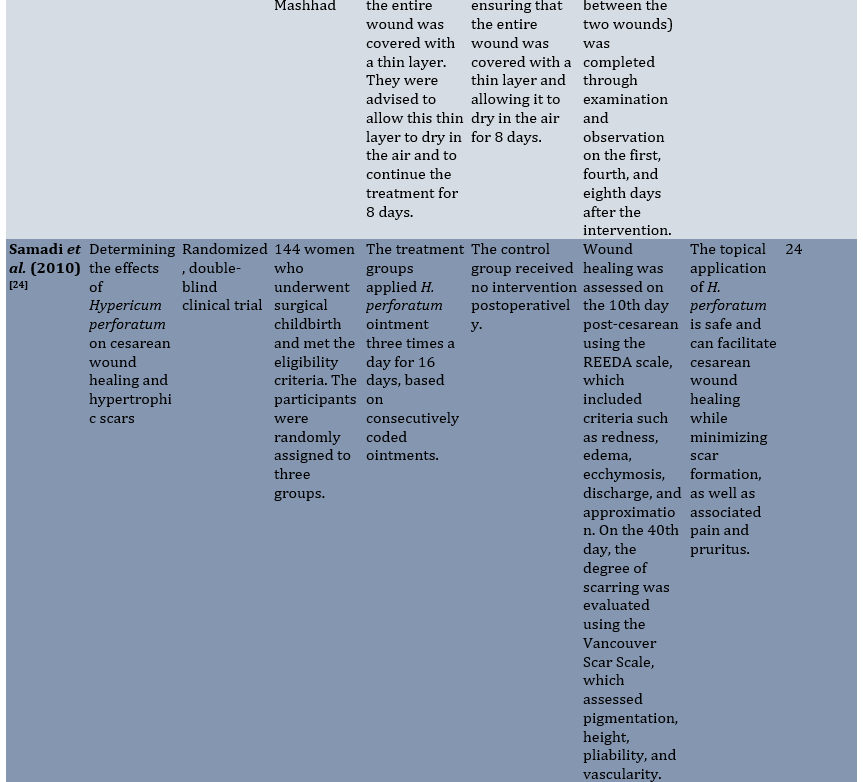

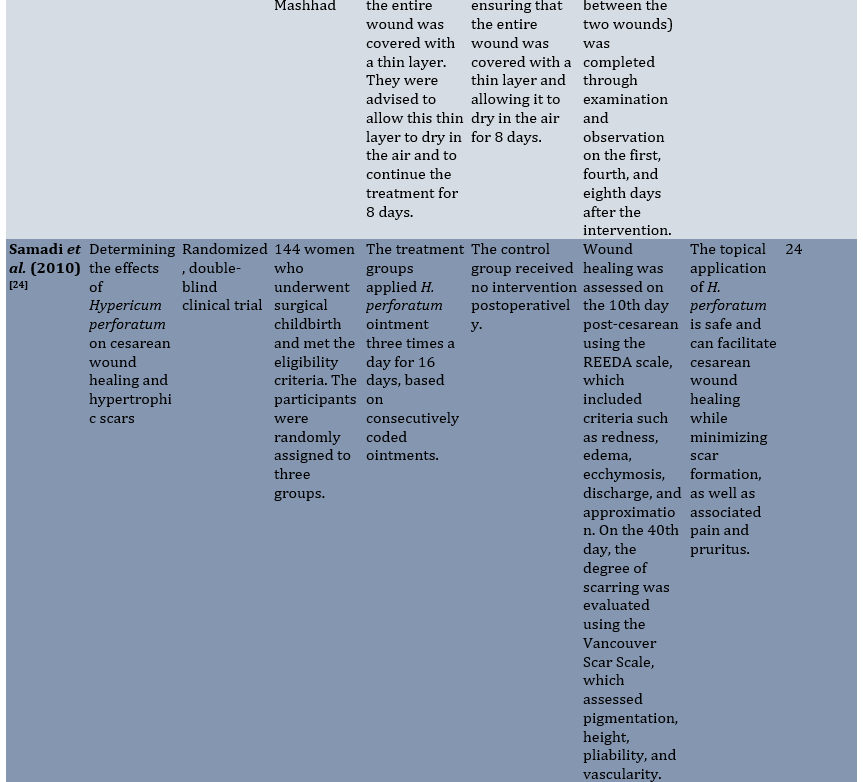

H. perforatum

In a double-blind clinical trial, the effect of H. perforatum on cesarean wound management was investigated in 144 participants who were randomly assigned to three groups: the placebo group, the control group, and the H. perforatum group, with the control group not receiving any medication. The other two groups applied the placebo and H. perforatum ointment three times a day for 16 days. On the 10th day of treatment, the groups were compared using the REEDA scale. There was a significant difference between the groups in terms of wound healing and scar formation, indicating that H. perforatum could accelerate the healing process and result in very little scarring [24].

C. longa

Turmeric extract was studied in two research investigations on cesarean wound healing. The first study was a double-blind clinical trial involving 181 pregnant women who visited hospitals for cesarean sections and were randomly divided into three groups: intervention, placebo, and control. The intervention group applied a gel containing turmeric extract, while the placebo group applied a gel without turmeric extract, both twice a day on the wound site for 14 days. The control group did not receive any treatment. The wound site was assessed using the REEDA scale on the days before the intervention, as well as on day 7 and day 14. The wound edema score showed a statistically significant difference between the intervention and placebo groups on days 7 and 14 after the cesarean section. The REEDA score in the turmeric group demonstrated a statistically significant difference compared to that of the placebo and control groups on days 7 and 14. Turmeric was effective in promoting faster healing of cesarean section wounds. The use of turmeric is suggested to reduce complications associated with cesarean section wounds [25]. In another study, the effects of turmeric extract and honey on pain and healing of cesarean section wounds were investigated in 56 female white mice aged 2-4 months and weighing between 150-300 g. The mice were divided into three groups: one receiving 50% turmeric extract, another receiving 75% turmeric extract, and the third receiving honey. Turmeric extract was administered twice a day, while the two honey groups received honey once and twice a day, respectively, and were evaluated using the REEDA scale. These two studies indicate turmeric’s ability to accelerate wound healing [26].

O. europaea

In a clinical trial study, the effect of olive ointment was investigated on the pain and healing of cesarean section wounds in 103 mothers who were randomly divided into three groups. There were 34 people in the placebo group, 35 people in the control group, and 34 people in the intervention group. The olive ointment and placebo groups used the ointment twice a day from the second day to ten days after cesarean section, whereas the control group received no treatment. Then, using the REEDA scale, all three groups were evaluated on the second and 10th day after cesarean section. There was a statistically significant difference between the three groups in terms of wound healing score on the 10th day after cesarean section. The inter-group comparison showed a statistically significant difference between the intervention and placebo groups and the intervention and control groups in the number of people who achieved complete recovery (zero scores on the REDA scale) on the 10th day. Olive ointment accelerates the wound healing process (Table 1) [14].

Table 1. Characteristics of the evaluated studies

Discussion

This systematic review assessed the efficacy of herbal products used in clinical trials for cesarean wound healing. Plants and plant products have long been utilized for wound healing [29]. Several herbs have been suggested for healing cesarean wounds, and some of these medicinal plants have been employed in folk medicine. The included studies assessed plants such as flax, Aloe vera, grape seed, marigold, calendula, and turmeric. All these plants have been effective in accelerating the healing of cesarean wounds. Among the investigated plants, only turmeric was studied in two trials, while the other plants were assessed in a limited number of studies; thus, conclusions and accurate interpretations of the results cannot be drawn. One of the investigated plants is flax. The effect of flaxseed oil was evaluated in a study [28]. In several studies, flax has been used to heal skin wounds and has shown positive results in accelerating wound healing [30-36]. Flax, which contains effective compounds such as essential fatty acids, unsaturated fatty acids, omega-3, and omega-6, exerts therapeutic effects on wound healing by regulating cell penetration, promoting angiogenesis, increasing fibroblast deposition, and improving skin elasticity against rapid wound contraction [36].

Another plant examined in this study is grape seed, which has been investigated in several studies involving human and animal samples for healing skin wounds [29, 37], demonstrating confirmed healing effects. The grape seed extract is rich in flavonoids, with the primary flavonoids being procyanidolic oligomers (proanthocyanidins), which possess antioxidant properties [38]. Proanthocyanidins are a subgroup of flavonoids, and their antioxidant properties are beneficial in wound healing. Grape seed extract is a very rich source of proanthocyanidins. The proanthocyanidins present in grape seeds, along with other flavonoids, can play a significant role in the healing process of skin wounds [39].

Another plant that we studied for its ability to accelerate the healing of cesarean wounds is Aloe vera [40-43]. In the included studies, the healing effect of Aloe vera on various types of wounds has been confirmed. Beta-sitosterol is one of the final products of Aloe vera gel decomposition and has potential angiogenic activity. The process of angiogenesis is crucial in wound healing [44]. Glycoproteins in Aloe vera gel inhibit swelling and pain while accelerating wound healing, and its polysaccharides also play a role in stimulating wound healing. Additionally, Aloe vera increases the production and secretion of collagen at the wound site. Furthermore, establishing transverse connections between these fibers enhances the strength of the skin structure in the wound area [44, 45]. However, some studies have not confirmed the effect of Aloe vera gel on accelerating wound healing. A study on the effect of Aloe vera gel on the healing of longitudinal and transverse incisions caused by abdominal surgery in women reported that the healing duration for both types of incisions was longer [46]. In the present study, eight days after the cesarean section, Aloe vera gel showed no significant difference in wound healing compared to the control group, which is consistent with this previous study. The difference in results may be attributed to variations in the method of application, dosage, timing of the herbal treatment, and the presence of infection in the wound. In the reviewed study, a single dose of Aloe vera gel was administered for 24 hours [22]. The effect of accelerating recovery may require repeated dosing.

Calendula is another herb that was studied for cesarean wound healing in this study. This plant is used topically in traditional medicine to treat skin lesions, including first-degree burns, boils, bruises, and skin rashes [47]. Several studies involving both animal and human samples have investigated the effect of this plant on the healing of various types of wounds [35, 47-52]. Different results have been reported regarding the therapeutic effects of calendula on wound healing. Most studies demonstrated effectiveness in acute wound healing, showing accelerated inflammation and increased production of granulation tissue in the groups treated with calendula extract compared to the control group. However, the results concerning the treatment of chronic wounds, including diabetic wounds and burns, are controversial [53]. Therefore, to further investigate the effect of calendula on skin wound healing, more studies with appropriate and well-designed sample sizes are needed.

H. perforatum was also investigated for its ability to accelerate the healing of cesarean wounds. Several studies involving both animal and human samples have demonstrated the positive effects of this plant on wound healing [45, 54-56]. Calendula acts through various mechanisms and is involved in every step of the wound healing process, including re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, wound contraction, and connective tissue formation. The extract of H. perforatum increases collagen deposition and regeneration, reduces inflammation, inhibits fibroblast migration, and promotes epithelialization by increasing the number of polygonal-shaped fibroblasts and the number of collagen strands within the fibroblasts. H. perforatum extract also modulates the immune response and reduces inflammation, thereby improving the healing process by inhibiting the production of inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, as well as the gene expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase, which accelerates wound healing [57].

Turmeric is another plant that was investigated in this study. The healing properties of turmeric have been explored and confirmed in several studies [58-61]. Research has shown that, due to its composition, turmeric is involved in wound healing through various mechanisms, such as modulating physiological and molecular events during the inflammatory phase, exerting antioxidant effects, and facilitating collagen synthesis and migration. Additionally, curcumin is beneficial for epithelialization and the apoptotic processes of inflammatory cells at the wound site. Furthermore, curcumin mediates the penetration of fibroblasts into the wound area [62]. In traditional medicine, olive is often used to accelerate the wound healing process [63]. The results of several studies involving both human and animal samples have confirmed the positive effects of olive oil in accelerating wound healing [64-67].

Although the results of these studies indicate that these plants are effective in the healing of cesarean section wounds, the number of studies on each product is limited, making it difficult to reach a scientific and accurate conclusion. Thus, more studies with appropriate designs should be conducted to investigate the effects of these herbs and to compare different medicinal forms and their various dosages. Additionally, while their mechanisms of action have been identified in laboratory settings, further investigation is needed in clinical settings. Therefore, the mechanisms of their effects on the wound healing process in clinical settings may differ and require additional research.

These plants influence wound healing even in the short term. Although studies have shown that each of these plants contains different active ingredients and affects the wound healing process through various mechanisms, they share common properties, such as anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant effects. The antibacterial and antimicrobial properties of these plants can reduce the risk of infection and create an environment free of bacteria and germs. This condition can be effective in accelerating wound healing [19]. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory properties of these plants represent another common mechanism in wound healing. These properties help establish a balance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, leading to improved healing of surgical wounds [20]. Due to existing sanctions affecting the Iranian scientific community, it was not possible to search all the databases; thus, there may be other studies that we could not examine in this study. This limitation is the most significant constraint of our research.

The number of studies on accelerating the healing of cesarean section wounds using plants is very limited. Some of these plants have been studied in human samples for the healing of other types of wounds, and their mechanisms of action in accelerating wound healing have been identified in laboratory settings. Therefore, it is recommended that more studies be conducted on each of the plants using different medicinal forms, doses, and methods of administration to determine the best pharmaceutical form and the most effective dose that maximizes satisfaction and comfort for women. Additionally, in some of these studies, possible side effects were not mentioned. It is suggested that future studies pay attention to the side effects of the studied plants and report them.

Conclusion

All the investigated plants are effective in healing cesarean wounds, although some of them, such as Aloe vera gel, have only a short-term effect.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their gratitude to the researchers whose findings were utilized in this study.

Ethical Permissions: Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Goudarzi F (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (50%); Hekmatzadeh SF (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%)

Funding/Support: Not applicable.

Despite the global emphasis on promoting physiological delivery, cesarean section remains one of the most common surgeries worldwide [1]. The prevalence of cesarean sections varies among different countries, ranging from 20% in France to 60% in some regions of Latin America [2]. The prevalence of cesarean sections is also high in Iran. According to the World Health Organization, the rate of cesarean sections in Iran in 2018 was 45.85% [3]. With the increase in the cesarean section rate, its side effects, such as hematoma, infection of the surgical site, wound dehiscence, and pain, also increase [4].

Complications resulting from cesarean wounds can occur in 2.5% to 34% of cesarean cases. One of the most significant complications of cesarean wounds is improper repair, which can lead to wound infection [5]. Wound infection, hematoma, and wound dehiscence are among the most common complications of cesarean section, leading to the mother’s re-hospitalization and frequent visits to the doctor, which can impose an economic burden on both the family and society [6]. Pain caused by the cesarean section wound can weaken the immune system, increase oxygen consumption by the myocardium, and lead to hypoglycemia, which causes delays in wound healing, as well as disturbances in bowel movements and decreased respiratory function [7]. In addition to the recovery period after surgery, women who undergo cesarean sections are also experiencing the postpartum period. In other words, in addition to managing the complications and inconveniences related to the cesarean section, they must also be able to breastfeed and care for their babies, thereby requiring additional support [8]. However, the scar and pain caused by cesarean section can interfere with the mother’s proper positioning for breastfeeding [9]. Therefore, pain management and the acceleration of wound healing after cesarean section are critical components of mother and baby care protocols and breastfeeding [10].

Wound healing involves coordinated repair responses that begin after surgery or trauma and lead to tissue regeneration. These responses are closely related to pre-operative and post-operative treatments, as well as trauma management. The healing process for all wounds occurs gradually and includes three stages: the inflammatory phase, the proliferation phase, and the maturation phase [11]. For the management of surgical wounds, including cesarean sections, there is a need for a comprehensive program aimed at care, proper wound repair in the shortest time possible, prevention of complications such as infection, wound dehiscence, improper scar formation, pain reduction, and facilitating the individual’s return to normal life [12]. Despite numerous investigations, no standard method has been established for the management of surgical wounds. However, some medications, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and narcotic analgesics, are used to manage pain and accelerate the healing of cesarean wounds. These medications are associated with side effects, such as nausea, respiratory discomfort, gastrointestinal bleeding, and itching [10]. In addition to being costly, many drugs available for wound management can cause issues such as allergies and drug resistance [13].

Due to the limited success of existing treatment methods, researchers are increasingly inclined to explore complementary medicine [14]. Consequently, the use of complementary medicine, including herbal therapy, is on the rise for managing pain and accelerating the healing of cesarean section wounds [15]. Traditional healers have been recommending the local use of certain plants to heal wounds caused by injuries and burns to their patients for many years. In general, medicinal plants for wound healing are cost-effective, affordable, and safe [13]. On the other hand, given the special considerations regarding breastfeeding, studies have reported that mothers are reluctant to use chemical drugs during this period due to concerns about the drugs being secreted in breast milk and their potential effects on the baby. Therefore, the use of medicinal plants during this time is more favorable among mothers [16].

The World Health Organization also reported that 80% of the world’s population uses medicinal plants as part of their treatment during breastfeeding [17]. Overall, herbal medicines with anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects are promising candidates for wound healing [18]. The anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties of plants can create an environment free of bacteria and germs, as well as provide a balanced environment in terms of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, which can be effective in accelerating the wound healing process [19, 20]. Some plants, such as flax (Linum usitatissimum) [21], grape seed [18], Aloe vera [22], calendula (Calendula officinalis) [23], Hypericum perforatum [24], turmeric (Curcuma longa) [25, 26], and olive (Olea europaea), are effective in cesarean wound healing [14]. However, the results remain limited and non-clinical. Considering that traditional medicine has long been used in Iran and that there is an increasing demand for medicinal plants, and given that no study has assessed the effects of medicinal plants on wound healing, especially cesarean section wounds, in Iran, the present study aimed to systematically review the effectiveness of herbal products examined in clinical trials for the healing of cesarean section wounds. The results can be applied in clinical settings.

Information and Methods

This review study was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Search strategy

Clinical trials examining the effectiveness of herbal compounds in the treatment and acceleration of cesarean wound healing were searched in both English and Persian databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Scopus, Magiran, SID, and Iranmedex, with no time limit until April 2024. Keywords, including “cesarean section,” “wound healing,” “herbal medicine,” “complementary medicine,” and “alternative care,” available on MeSH, were used for the search. Additionally, AND and OR operators were employed in the search.

Inclusion criteria included clinical trials, the prescription of herbal products for cesarean wound healing, and studies published in Persian and English databases. Exclusion criteria consisted of a lack of access to the full text of articles, letters to the editor, commentaries, articles presented at conferences, preprinted articles, retracted articles, theses, protocols, review articles, and trials involving non-plant products.

Selection of articles

Out of 471 articles obtained from the initial search and five articles sourced from other means, 453 articles remained after removing duplicates. Following a review of the titles and abstracts, 94 articles were screened for full text, and ultimately, eight articles met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). All obtained articles were checked using EndNote version 21 for duplicate detection. Subsequently, the titles and abstracts were reviewed, followed by a full review of the articles in the second stage, conducted separately by two researchers. Finally, the articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two authors.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study selection process

Data extraction

Initially, a file for data extraction was designed by the authors. Then, the two authors individually reviewed the entered articles based on the prepared file and extracted the relevant data. The items in the prepared file included the characteristics of the research, such as the first author, year of publication, purpose of the study, study design, number of samples, intervention and control groups, type of intervention, method of measuring the results, duration of the investigation, and the results available in the CONSORT checklist. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two researchers, after which the content was evaluated for quality.

Quality assessment of the articles

The quality of the articles was evaluated using the CONSORT 2018 checklist [27], which consists of 45 items assessing seven aspects, including title, abstract, introduction, methods and findings, discussion, and other relevant sections. The selected articles received a score of one for each desired item present in each section and a score of zero if that item was absent. The overall quality score of each article was calculated based on the total number of items in the CONSORT checklist; thus, the highest possible score is 45, while the lowest score is zero.

Findings

Characteristics of the studies

Eight studies were evaluated with their publication dates ranging from 2010 to 2024. The articles originated from Iran (87.5%) [14, 18, 22-25, 28] and India (12.5%) [26], with a total sample size of 699 individuals. All clinical trials were randomized. In the studies, the healing process was assessed using the REEDA scale over eight to fourteen days. In five articles, the herbal product used was prepared in the form of a cream [14, 18, 21, 23, 24], which was applied twice a day to the wound area. In one study, the product was utilized as a dressing [22], and applied once within the first 24 hours after cesarean section. In two articles, the herbal product was prepared as a gel [25, 26].

The quality of the articles evaluated by the CONSORT tool was between 22 and 24, which indicates the average quality of the articles. Due to the small number of clinical trial studies in this field, it was not possible to assess the risk of publication bias.

The herbal product used to accelerate the cesarean wound healing

The plants examined in this review included flax (L. usitatissimum), grape seed, Aloe vera, calendula (C. officinalis), H. perforatum, turmeric (C. longa), and olive. Their derived products were applied topically in the form of ointments and gels.

L. usitatissimum

L. usitatissimum (flax) as an ointment was studied in a double-blind clinical trial conducted in 2019 for the management of cesarean wounds involving 120 women eligible for cesarean delivery at Imam Reza and Shahid Hashemi Hospitals in Mashhad. To evaluate wound healing, the REEDA scale was used on the first, fourth, and eighth days after the intervention. This scale assesses redness, edema, bruising, discharge, and the distance between the two edges of the wound, and it is completed through examination and observation. Each parameter on this scale is scored from zero to three. The mothers in both the flax and placebo groups were instructed to apply the ointment twice a day after washing and drying the sutures. They were advised to apply a finger-sized amount of the medication to the wound until a thin layer covered the entire area, allowing this layer to dry in the air, and to continue the treatment for eight days. There was a statistically significant difference between the intervention and placebo groups, as well as between the flax and control groups, in terms of cesarean wound healing at four and eight days post-intervention. Additionally, the Friedman test indicated significant differences in the changes in the REEDA scale across all three groups on different days (p<0.0001). During the study, none of the mothers reported any side effects [28].

Grape seed

A double-blind clinical trial investigated the effect of grape seed extract as an ointment in 2019 on cesarean wound healing. In this study, 129 mothers were randomly divided into three groups; one group received a product containing 2.5% grape seed extract, another group received 5% extract, and the third group received Vaseline. There were 42 participants in the 5% group, 41 participants in the 2.5% group, and 42 participants in the Vaseline group. All three groups applied the ointments topically starting from the second day post-cesarean for 15 days, twice a day, according to the provided instructions. The groups were then evaluated for wound healing before the intervention, as well as on the 6th and 14th days after cesarean section, using the REEDA scale. On the sixth day of the intervention, there was no significant difference in the average scores of redness and discharge among the three groups. However, the average scores of edema, ecchymosis, and approximation were statistically significantly different across the groups. By the 14th day after the intervention, the three groups exhibited statistically significant differences in the average scores of redness, edema, ecchymosis, and approximation. The mean total scores of the REEDA scale were significantly different between the 5% ointment and 2.5% ointment groups, as well as between the 5% ointment and Vaseline groups on both the 6th and 14th days after the intervention. However, the mean total scores did not show a significant difference between the 2.5% ointment and Vaseline groups six days after the intervention. It was concluded that 5% grape seed extract may have beneficial therapeutic effects on cesarean section wound healing [18].

Aloe vera

A double-blind clinical trial investigated the effect of Aloe vera on cesarean section wounds in 2015, involving 90 participants who were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups (45 participants per group). Both groups received diclofenac suppositories and cefazolin ampoules. In the intervention group, the wound was bandaged with Aloe vera gel, while the control group received a simple dressing (dry gauze). The REEDA scale was used to evaluate both groups, with scores ranging from 0 to 15, where a higher score indicated poorer healing. Wound healing was assessed 24 hours after surgery and continued until eight days post-surgery. There was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of the wound healing score 24 hours after the operation (P=0.003). On the 8th day of the study, the total REEDA scale score was lower in the intervention group, although this difference was not statistically significant [22].

C. officinalis

A double-blind clinical trial assessed the effect of C. officinalis on cesarean wound healing in 2018, involving 72 participants who were randomly divided into intervention and control groups. The intervention group applied a 2% marigold hydroalcoholic ointment twice a day for ten days, while the control group did not use any ointment. Both groups were evaluated before the intervention and on days three, six, and nine after cesarean section based on the REEDA scale. The REEDA scale score ranged from 0 to 15, with a higher score indicating poorer healing. In the C. officinalis group, lower scores were observed on the third, sixth, and ninth days after treatment in both the total score and the five criteria of the REEDA scale, which included redness, edema, discharge, ecchymosis, and approximation of the wound edges. Statistically, there was a significant difference in wound healing between the intervention and control groups [23].

H. perforatum

In a double-blind clinical trial, the effect of H. perforatum on cesarean wound management was investigated in 144 participants who were randomly assigned to three groups: the placebo group, the control group, and the H. perforatum group, with the control group not receiving any medication. The other two groups applied the placebo and H. perforatum ointment three times a day for 16 days. On the 10th day of treatment, the groups were compared using the REEDA scale. There was a significant difference between the groups in terms of wound healing and scar formation, indicating that H. perforatum could accelerate the healing process and result in very little scarring [24].

C. longa

Turmeric extract was studied in two research investigations on cesarean wound healing. The first study was a double-blind clinical trial involving 181 pregnant women who visited hospitals for cesarean sections and were randomly divided into three groups: intervention, placebo, and control. The intervention group applied a gel containing turmeric extract, while the placebo group applied a gel without turmeric extract, both twice a day on the wound site for 14 days. The control group did not receive any treatment. The wound site was assessed using the REEDA scale on the days before the intervention, as well as on day 7 and day 14. The wound edema score showed a statistically significant difference between the intervention and placebo groups on days 7 and 14 after the cesarean section. The REEDA score in the turmeric group demonstrated a statistically significant difference compared to that of the placebo and control groups on days 7 and 14. Turmeric was effective in promoting faster healing of cesarean section wounds. The use of turmeric is suggested to reduce complications associated with cesarean section wounds [25]. In another study, the effects of turmeric extract and honey on pain and healing of cesarean section wounds were investigated in 56 female white mice aged 2-4 months and weighing between 150-300 g. The mice were divided into three groups: one receiving 50% turmeric extract, another receiving 75% turmeric extract, and the third receiving honey. Turmeric extract was administered twice a day, while the two honey groups received honey once and twice a day, respectively, and were evaluated using the REEDA scale. These two studies indicate turmeric’s ability to accelerate wound healing [26].

O. europaea

In a clinical trial study, the effect of olive ointment was investigated on the pain and healing of cesarean section wounds in 103 mothers who were randomly divided into three groups. There were 34 people in the placebo group, 35 people in the control group, and 34 people in the intervention group. The olive ointment and placebo groups used the ointment twice a day from the second day to ten days after cesarean section, whereas the control group received no treatment. Then, using the REEDA scale, all three groups were evaluated on the second and 10th day after cesarean section. There was a statistically significant difference between the three groups in terms of wound healing score on the 10th day after cesarean section. The inter-group comparison showed a statistically significant difference between the intervention and placebo groups and the intervention and control groups in the number of people who achieved complete recovery (zero scores on the REDA scale) on the 10th day. Olive ointment accelerates the wound healing process (Table 1) [14].

Table 1. Characteristics of the evaluated studies

Discussion

This systematic review assessed the efficacy of herbal products used in clinical trials for cesarean wound healing. Plants and plant products have long been utilized for wound healing [29]. Several herbs have been suggested for healing cesarean wounds, and some of these medicinal plants have been employed in folk medicine. The included studies assessed plants such as flax, Aloe vera, grape seed, marigold, calendula, and turmeric. All these plants have been effective in accelerating the healing of cesarean wounds. Among the investigated plants, only turmeric was studied in two trials, while the other plants were assessed in a limited number of studies; thus, conclusions and accurate interpretations of the results cannot be drawn. One of the investigated plants is flax. The effect of flaxseed oil was evaluated in a study [28]. In several studies, flax has been used to heal skin wounds and has shown positive results in accelerating wound healing [30-36]. Flax, which contains effective compounds such as essential fatty acids, unsaturated fatty acids, omega-3, and omega-6, exerts therapeutic effects on wound healing by regulating cell penetration, promoting angiogenesis, increasing fibroblast deposition, and improving skin elasticity against rapid wound contraction [36].

Another plant examined in this study is grape seed, which has been investigated in several studies involving human and animal samples for healing skin wounds [29, 37], demonstrating confirmed healing effects. The grape seed extract is rich in flavonoids, with the primary flavonoids being procyanidolic oligomers (proanthocyanidins), which possess antioxidant properties [38]. Proanthocyanidins are a subgroup of flavonoids, and their antioxidant properties are beneficial in wound healing. Grape seed extract is a very rich source of proanthocyanidins. The proanthocyanidins present in grape seeds, along with other flavonoids, can play a significant role in the healing process of skin wounds [39].

Another plant that we studied for its ability to accelerate the healing of cesarean wounds is Aloe vera [40-43]. In the included studies, the healing effect of Aloe vera on various types of wounds has been confirmed. Beta-sitosterol is one of the final products of Aloe vera gel decomposition and has potential angiogenic activity. The process of angiogenesis is crucial in wound healing [44]. Glycoproteins in Aloe vera gel inhibit swelling and pain while accelerating wound healing, and its polysaccharides also play a role in stimulating wound healing. Additionally, Aloe vera increases the production and secretion of collagen at the wound site. Furthermore, establishing transverse connections between these fibers enhances the strength of the skin structure in the wound area [44, 45]. However, some studies have not confirmed the effect of Aloe vera gel on accelerating wound healing. A study on the effect of Aloe vera gel on the healing of longitudinal and transverse incisions caused by abdominal surgery in women reported that the healing duration for both types of incisions was longer [46]. In the present study, eight days after the cesarean section, Aloe vera gel showed no significant difference in wound healing compared to the control group, which is consistent with this previous study. The difference in results may be attributed to variations in the method of application, dosage, timing of the herbal treatment, and the presence of infection in the wound. In the reviewed study, a single dose of Aloe vera gel was administered for 24 hours [22]. The effect of accelerating recovery may require repeated dosing.

Calendula is another herb that was studied for cesarean wound healing in this study. This plant is used topically in traditional medicine to treat skin lesions, including first-degree burns, boils, bruises, and skin rashes [47]. Several studies involving both animal and human samples have investigated the effect of this plant on the healing of various types of wounds [35, 47-52]. Different results have been reported regarding the therapeutic effects of calendula on wound healing. Most studies demonstrated effectiveness in acute wound healing, showing accelerated inflammation and increased production of granulation tissue in the groups treated with calendula extract compared to the control group. However, the results concerning the treatment of chronic wounds, including diabetic wounds and burns, are controversial [53]. Therefore, to further investigate the effect of calendula on skin wound healing, more studies with appropriate and well-designed sample sizes are needed.

H. perforatum was also investigated for its ability to accelerate the healing of cesarean wounds. Several studies involving both animal and human samples have demonstrated the positive effects of this plant on wound healing [45, 54-56]. Calendula acts through various mechanisms and is involved in every step of the wound healing process, including re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, wound contraction, and connective tissue formation. The extract of H. perforatum increases collagen deposition and regeneration, reduces inflammation, inhibits fibroblast migration, and promotes epithelialization by increasing the number of polygonal-shaped fibroblasts and the number of collagen strands within the fibroblasts. H. perforatum extract also modulates the immune response and reduces inflammation, thereby improving the healing process by inhibiting the production of inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, as well as the gene expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase, which accelerates wound healing [57].

Turmeric is another plant that was investigated in this study. The healing properties of turmeric have been explored and confirmed in several studies [58-61]. Research has shown that, due to its composition, turmeric is involved in wound healing through various mechanisms, such as modulating physiological and molecular events during the inflammatory phase, exerting antioxidant effects, and facilitating collagen synthesis and migration. Additionally, curcumin is beneficial for epithelialization and the apoptotic processes of inflammatory cells at the wound site. Furthermore, curcumin mediates the penetration of fibroblasts into the wound area [62]. In traditional medicine, olive is often used to accelerate the wound healing process [63]. The results of several studies involving both human and animal samples have confirmed the positive effects of olive oil in accelerating wound healing [64-67].

Although the results of these studies indicate that these plants are effective in the healing of cesarean section wounds, the number of studies on each product is limited, making it difficult to reach a scientific and accurate conclusion. Thus, more studies with appropriate designs should be conducted to investigate the effects of these herbs and to compare different medicinal forms and their various dosages. Additionally, while their mechanisms of action have been identified in laboratory settings, further investigation is needed in clinical settings. Therefore, the mechanisms of their effects on the wound healing process in clinical settings may differ and require additional research.

These plants influence wound healing even in the short term. Although studies have shown that each of these plants contains different active ingredients and affects the wound healing process through various mechanisms, they share common properties, such as anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant effects. The antibacterial and antimicrobial properties of these plants can reduce the risk of infection and create an environment free of bacteria and germs. This condition can be effective in accelerating wound healing [19]. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory properties of these plants represent another common mechanism in wound healing. These properties help establish a balance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, leading to improved healing of surgical wounds [20]. Due to existing sanctions affecting the Iranian scientific community, it was not possible to search all the databases; thus, there may be other studies that we could not examine in this study. This limitation is the most significant constraint of our research.

The number of studies on accelerating the healing of cesarean section wounds using plants is very limited. Some of these plants have been studied in human samples for the healing of other types of wounds, and their mechanisms of action in accelerating wound healing have been identified in laboratory settings. Therefore, it is recommended that more studies be conducted on each of the plants using different medicinal forms, doses, and methods of administration to determine the best pharmaceutical form and the most effective dose that maximizes satisfaction and comfort for women. Additionally, in some of these studies, possible side effects were not mentioned. It is suggested that future studies pay attention to the side effects of the studied plants and report them.

Conclusion

All the investigated plants are effective in healing cesarean wounds, although some of them, such as Aloe vera gel, have only a short-term effect.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their gratitude to the researchers whose findings were utilized in this study.

Ethical Permissions: Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Goudarzi F (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (50%); Hekmatzadeh SF (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%)

Funding/Support: Not applicable.

Keywords:

References

1. Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A, et al. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: The 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006;367(9525):1819-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68704-7]

2. Zbiri S, Rozenberg P, Goffinet F, Milcent C. Cesarean delivery rate and staffing levels of the maternity unit. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207379. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0207379]

3. Adibi P, Kalani N, Razavi BM, Mehrpour S, Zarei T, Malekshoar M, et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods of pain control in women undergoing caesarean section: A narrative review. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2022;25(7):91-112. [Persian] [Link]

4. Basha SL, Rochon ML, Quiñones JN, Coassolo KM, Rust OA, Smulian JC. Randomized controlled trial of wound complication rates of subcuticular suture vs staples for skin closure at cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(3):285.e1-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.011]

5. Fraser DM, Cooper MA. Myles textbook for midwives. 14th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. [Link]

6. Pallasmaa N, Ekblad U, Aitokallio‐Tallberg A, Uotila J, Raudaskoski T, Ulander VM, et al. Cesarean delivery in Finland: Maternal complications and obstetric risk factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(7):896-902. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/00016349.2010.487893]

7. Chanif C, Petpichetchian W, Chongchareon W. Does foot massage relieve acute postoperative pain? A literature review. Nurse Media J Nurs. 2013;3(1):483-97. [Link]

8. Pillitteri A. Maternal & child health nursing: Care of the childbearing and childrearing family. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Link]

9. Niazi A, Yousefzadeh S, Rakhshandeh H, Esmaeili H. Comparison of purslane cream and lanolin on nipple pain among breastfeeding women: A randomized clinical trial. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2018;20(12):77-85. [Persian] [Link]

10. Sepehrirad M, Bahrami H, Noras M. The role of complementary medicine in control of premenstrual syndrome evidence based (regular review study). Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2016;19(24):11-22. [Persian] [Link]

11. Campos AC, Groth AK, Branco AB. Assessment and nutritional aspects of wound healing. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(3):281-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282fbd35a]

12. Roseborough IE, Grevious MA, Lee RC. Prevention and treatment of excessive dermal scarring. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(1):108-16. [Link]

13. Kebriti K, Naderi MS, Tabaie SM, Hesami Tackllou S. Herbal medicine efficiency in wound healing. Laser Med. 2020;16(4):32-41. [Persian] [Link]

14. Taheri M, Amiri-Farahani L, Haghani S, Shokrpour M, Shojaii A. The effect of olive cream on pain and healing of caesarean section wounds: A randomised controlled clinical trial. J Wound Care. 2022;31(3):244-53. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/jowc.2022.31.3.244]

15. Nahas R, Sheikh O. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(6):659-63. [Link]

16. Khojastehfard Z, Yazdimoghaddam H, Abdollahi M, Karimi FZ. Effect of herbal medicines on postpartum hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Care J. 2021;11(1):62-74. [Link]

17. Kim HS. Do not put too much value on conventional medicines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100(1-2):37-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.030]

18. Izadpanah A, Soorgi S, Geraminejad N, Hosseini M. Effect of grape seed extract ointment on cesarean section wound healing: A double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;35:323-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.03.011]

19. Shahrahmani H, Kariman N, Jannesari S, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Mirzaei M, Shahrahmani N. The effect of Camellia sinensis ointment on perineal wound healing in primiparous women. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2018;20(5):7-15. [Persian] [Link]

20. Butt MS, Sultan MT. Green tea: Nature's defense against malignancies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2009;49(5):463-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10408390802145310]

21. Soleimani M, Yousefzadeh S, Salari R, Mousavi Vahed SH, Mazloum SR. The effects of flaxseed ointment on cesarean wound healing: Randomized clinical trial. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2019;22(9):64-71. [Persian] [Link]

22. Molazem Z, Mohseni F, Younesi M, Keshavarzi S. Aloe vera gel and cesarean wound healing; A randomized controlled clinical trial. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;7(1):203-9. [Link] [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v7n1p203]

23. Jahdi F, Khabbaz AH, Kashian M, Taghizadeh M, Haghani H. The impact of calendula ointment on cesarean wound healing: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7(5):893-7. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_121_17]

24. Samadi S, Khadivzadeh T, Emami A, Moosavi NS, Tafaghodi M, Behnam HR. The effect of hypericum perforatum on the wound healing and scar of cesarean. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(1):113-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/acm.2009.0317]

25. Mahmudi G, Nikpour M, Azadbackt M, Zanjani R, Jahani M, Aghamohammadi A, et al. The impact of turmeric cream on healing of caesarean scar. West Indian Med J. 2015;64(4):400-6. [Link] [DOI:10.7727/wimj.2014.196]

26. Usman AN, Sartini S, Yulianti R, Kamsurya M, Oktaviana A, Nulandari Z, et al. Turmeric extract gel and honey in post-cesarean section wound healing: A preliminary study. F1000Res. 2023;12:1095. [Link] [DOI:10.12688/f1000research.134011.1]

27. Hopewell S, Boutron I, Moher D. CONSORT and its extensions for reporting clinical trials. In: Principles and practice of clinical trials. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 1-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-52677-5_188-1]

28. Soleimani M, Yousefzadeh S, Salari R, Vahed SHM, Mazloum SR. The effect of flaxseed ointment on intensity of cesarean wound pain: Randomized clinical trial. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2023;25(11):47‐55. [Persian] [Link]

29. Hemmati AA, Foroozan M, Houshmand G, Moosavi ZB, Bahadoram M, Maram NS. The topical effect of grape seed extract 2% cream on surgery wound healing. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;7(3):52-8. [Link] [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v7n3p52]

30. Rafiee S, Nekouyian N, Hosseini S, Sarabandi F, Chavoshi-Nejad M, Mohsenikia M, et al. Effect of topical linum usitatissimum on full thickness excisional skin wounds. Trauma Mon. 2017;22(6):e64930. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.39045]

31. Franco EDS, De Aquino CMF, Medeiros PLd, Evêncio LB, Góes AJdS, Maia MBdS. Effect of a semisolid formulation of Linum usitatissimum L. (Linseed) oil on the repair of skin wounds. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012(1):270752. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2012/270752]

32. Debas HT, Laxminarayan R, Straus SE. Complementary and alternative medicine. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2011. [Link]

33. McDaniel JC, Belury M, Ahijevych K, Blakely W. Omega‐3 fatty acids effect on wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(3):337-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00388.x]

34. Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453(7193):314-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/nature07039]

35. Ernst E, Cohen MH, Stone J. Ethical problems arising in evidence based complementary and alternative medicine. J Med Ethics. 2004;30(2):156-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/jme.2003.007021]

36. Sharil ATM, Ezzat MB, Widya L, Nurhakim MHA, Hikmah ARN, Zafira ZN, et al. Systematic review of flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) extract and formulation in wound healing. J Pharm Pharmacogn Res. 2022;10(1):1-12. [Link] [DOI:10.56499/jppres21.1125_10.1.1]

37. Sagliyan A, Benzer F, Kandemir F, Gunay C, Han M, Ozkaraca M. Beneficial effects of oral administrations of grape seed extract on healing of surgically induced skin wounds in rabbits. Revue de Medecine Veterinaire. 2012;163(1):11-7. [Link]

38. Bhatia S, Sharma K, Namdeo AG, Chaugule B, Kavale M, Nanda S. Broad-spectrum sun-protective action of Porphyra-334 derived from Porphyra vietnamensis. Pharmacognosy Res. 2010;2(1):45-9. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/0974-8490.60578]

39. Nassiri‐Asl M, Hosseinzadeh H. Review of the pharmacological effects of Vitis vinifera (Grape) and its bioactive compounds. Phytother Res. 2009;23(9):1197-204. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ptr.2761]

40. Avizhgan M. Aloe Vera gel as an effective and cheap option for treatment in chronic bed sores. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. 2004;13(50):45-51. [Persian] [Link]

41. Pezeshki B, Pouredalati M, Zolala S, Moeindarbary S, Kazemi K, Rakhsha M, et al. Comparison of the effect of aloe vera extract, breast milk, calendit-E, curcumin, lanolin, olive oil, and Purslane on healing of breast fissure in lactating mothers: A systematic reviwe. Int J Pediatr. 2020;8(2):10853-63. [Link]

42. Deng J, Li S, Peng Y, Chen Z, Wang C, Fan Z, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for previous cesarean scar defect: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020;99(50):e23630. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000023630]

43. Jia Y, Zhao G, Jia J. Preliminary evaluation: The effects of Aloe ferox Miller and Aloe arborescens Miller on wound healing. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120(2):181-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2008.08.008]

44. Minwuyelet T, Sewalem M, Gashe M. Review on therapeutic uses of Aloe vera. Glob J Pharmacol. 2017;11(2):14-20. [Link]

45. Atik N, Nandika A, Cyntia Dewi PI, Avriyanti E. Molecular mechanism of Aloe barbadensis Miller as a potential herbal medicine. Syst Rev Pharm. 2019;10(1):118-25. [Link]

46. Schmidt JM, Greenspoon JS. Aloe vera dermal wound gel is associated with a delay in wound healing. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(1):115-7. [Link]

47. Shafeie N, Naini AT, Jahromi HK. Comparison of different concentrations of Calendula officinalis gel on cutaneous wound healing. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2015;8(2):979-92. [Link] [DOI:10.13005/bpj/850]

48. Nicolaus C, Junghanns S, Hartmann A, Murillo R, Ganzera M, Merfort I. In vitro studies to evaluate the wound healing properties of Calendula officinalis extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;196:94-103. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2016.12.006]

49. Fronza M, Heinzmann B, Hamburger M, Laufer S, Merfort I. Determination of the wound healing effect of Calendula extracts using the scratch assay with 3T3 fibroblasts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;126(3):463-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.014]

50. Parente LM, Lino Júnior Rde S, Tresvenzol LM, Vinaud MC, De Paula JR, Paulo NM. Wound healing and anti‐inflammatory effect in animal models of Calendula officinalis L. growing in Brazil. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012(1):375671. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2012/375671]

51. Buzzi M, De Freitas F, De Barros Winter M. Therapeutic effectiveness of a Calendula officinalis extract in venous leg ulcer healing. J Wound Care. 2016;25(12):732-9. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/jowc.2016.25.12.732]

52. Rezai S, Rahzani K, Hekmatpou D, Rostami A. Effect of oral Calendula officinalis on second-degree burn wound healing. Scars Burn Heal. 2023;9:20595131221134053. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/20595131221134053]

53. Givol O, Kornhaber R, Visentin D, Cleary M, Haik J, Harats M. A systematic review of Calendula officinalis extract for wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27(5):548-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/wrr.12737]

54. Çobanoğlu A, Şendir M. The effect of hypericum perforatum oil on the healing process in the care of episiotomy wounds: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Integr Med. 2020;34:100995. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.eujim.2019.100995]

55. Altan A, Aras MH, Damlar İ, Gökçe H, Özcan O, Alpaslan C. The effect of hypericum perforatum on wound healing of oral mucosa in diabetic rats. Eur Oral Res. 2018;52(3):143-9. [Link] [DOI:10.26650/eor.2018.505]

56. Seyhan N. Evaluation of the healing effects of hypericum perforatum and curcumin on burn wounds in rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020(1):6462956. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2020/6462956]

57. Farasati Far B, Gouranmohit G, Naimi‐Jamal MR, Neysani E, El‐Nashar HA, El‐Shazly M, et al. The potential role of hypericum perforatum in wound healing: A literature review on the phytochemicals, pharmacological approaches, and mechanistic perspectives. Phytother Res. 2024;38(7):3271-95. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ptr.8204]

58. Golmakani N, Rabiei Motlagh E, Tara F, Assili J, Shakeri MT. The effects of turmeric (Curcuma longa L) ointment on healing of episiotomy site in primiparous women. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2009;11(4):29-39. [Persian] [Link]

59. Thangapazham RL, Sharma A, Maheshwari RK. Beneficial role of curcumin in skin diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:343-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_15]

60. Alven S, Nqoro X, Aderibigbe BA. Polymer-based materials loaded with curcumin for wound healing applications. Polymers. 2020;12(10):2286. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/polym12102286]

61. Kundu S, Biswas TK, Das P, Kumar S, De DK. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) rhizome paste and honey show similar wound healing potential: A preclinical study in rabbits. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2005;4(4):205-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1534734605281674]

62. Barchitta M, Maugeri A, Favara G, Magnano San Lio R, Evola G, Agodi A, et al. Nutrition and wound healing: An overview focusing on the beneficial effects of curcumin. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(5):1119. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijms20051119]

63. Zahmatkesh M, Rashidi M. Treatment of diabetic leg ulcer by local application of honey and olive oil mixture. J Med Plants. 2009;8(29):36-40. [Persian] [Link]

64. Melguizo-Rodríguez L, De Luna-Bertos E, Ramos-Torrecillas J, Illescas-Montesa R, Costela-Ruiz VJ, García-Martínez O. Potential effects of phenolic compounds that can be found in olive oil on wound healing. Foods. 2021;10(7):1642. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/foods10071642]

65. Bayir Y, Un H, Ugan RA, Akpinar E, Cadirci E, Calik I, et al. The effects of Beeswax, olive oil and butter impregnated bandage on burn wound healing. Burns. 2019;45(6):1410-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.burns.2018.03.004]

66. Karimi Z, Behnammoghadam M, Rafiei H, Abdi N, Zoladl M, Talebianpoor MS, et al. Impact of olive oil and honey on healing of diabetic foot: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:347-54. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/CCID.S198577]

67. Ghanbari A, Masoumi S, Leyli EK, Mahdavi-Roshan M, Mobayen M. Effects of flaxseed oil and olive oil on markers of inflammation and wound healing in burn patients: A randomized clinical trial. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2023;11(1):32-40. [Link]