Volume 5, Issue 4 (2024)

J Clinic Care Skill 2024, 5(4): 173-179 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1401.074

History

Received: 2024/07/23 | Accepted: 2024/10/21 | Published: 2024/10/31

Received: 2024/07/23 | Accepted: 2024/10/21 | Published: 2024/10/31

How to cite this article

Begjani J, Bagheri Moheb N, Haghani S, Babaei H. The Relationship between Alarm Fatigue and Clinical Competence in Neonatal Intensive Care Nurses in Kermanshah, Iran. J Clinic Care Skill 2024; 5 (4) :173-179

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-286-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-286-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Pediatrics, Imam Reza Hospital, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

2- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Pediatrics, Imam Reza Hospital, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (970 Views)

Introduction

Healthcare is one of the most important areas of sustainable development in human societies and is responsible for the important task of maintaining health. Among healthcare professionals, nurses are the largest group in treatment departments, especially special care departments [1]. Every year, 15 million premature newborns are born worldwide, of which half a million premature newborns are born in the United States of America. Iran is also one of the regions with a high prevalence of premature birth, where approximately 10% of births are premature and have a low birth weight [2]. Caring for sick and hospitalized newborns requires paying attention to the complex, special, critical and changing needs of newborns and having clinical competence, which is the main factor in providing quality care [3] and can improve the quality of nursing care and the survival rate of newborns along with the development of advanced equipment in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) [3, 4].

Competency was introduced as a concept in nursing by Johnson in the late 1960s, and Benner was the first to expand its use in clinical nursing [5, 6]. The WHO has defined clinical competence as a level of performance that represents the effective application of knowledge, skills, and judgment [7]. Clinical competence consists of seven dimensions, which include helping role, teaching-coaching, diagnostic functions, managing situations, therapeutic interventions, ensuring quality and work role [8, 9]. In newborn nursing, clinical competence is defined as having the knowledge, ability and skill to effectively and professionally perform all the care needed by newborns [10].

Inadequate competence of nurses is one of the predisposing factors for the occurrence of clinical errors in care units [11]. The results of some reports indicate that more than 80% of errors leading to secondary injuries of patients were due to negligence or insufficient clinical competence of nurses [12]. In Iran, the results of a study by Bahreini et al. showed that the level of clinical competence of nurses in some subscales, including teaching-coaching and ensuring quality, was unfavorable [13].

On the other hand, in intensive care units, where patients are under care in a critical condition, alarms are everywhere [14, 15]. The majority of patients in the neonatal intensive care unit are preterm newborns with physiologically immature functions who are at risk of serious complications [16]. Responding to alarms accounts for 35% of an intensive care nurse's working time [14]. In previous studies, it was estimated that more than 70% of clinical alarms do not require clinical intervention [16]. However, many alarms are considered false or clinically irrelevant [16, 17], and they even account for 85-99% of all alarms [14, 15, 18]. False alarms reduce response time and nurses' trust in alarms [15, 16], and they also cause disruptions in the planning and efficient performance of nurses and their distraction [19, 20]. This leads to nurses deactivating alarms, failing to respond appropriately, or reducing their volume [21]. Nurses consider these alarms as noisy alarms, causing discomfort, headaches and disrupting patient care, and this situation can cause them to suffer from alarm fatigue in the long run [21, 22]. Alarm fatigue occurs when caregivers are exposed to too many alarms, causing alarm desensitization [23] and delayed or even nonresponse to alarms, which can lead to serious patient harm and unsafe practices. It is known as an important issue of patient safety [15, 16, 24, 25], which was ranked by the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI) as one of the 10 most important technological threats to health (2016-2020) [21]. No similar study was found regarding the relationship between the Alarm Fatigue and Clinical Competence among Neonatal Intensive Care Nurses.

Given the importance of improving nursing care quality in neonatal intensive care units and the lack of studies on clinical competence in these settings, the research team decided to conduct this study. With several years of NICU experience, issues with monitoring alarms and devices were observed, as well as the frustration, headaches, and irritability these alarms cause nurses. This study aims to assess the relationship between alarm fatigue and clinical competence among neonatal intensive care nurses.

Instruments and Methods

Design and participants

This research was a correlational study conducted in neonatal intensive care units in Kermanshah, Iran in 2022-2023. This study included hospitals of Imam Reza, Dr. Mohammad Kermanshahi, Motazedi, Imam Hossein, Hazrat Masoumeh, Hazrat Abulfazl al-Abbas, Bisetun and Hakim. The census sampling method was used and all nurses entered the study (n=153). Of these, 140 people met the inclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria required participants to hold a bachelor's degree or higher in nursing, have at least six months of experience working in a neonatal intensive care unit, be in good physical and mental health as documented in their employment file [3], and have no hearing impairments [21].

Exclusion criteria included a lack of willingness to continue participation in the study, incomplete questionnaire submissions, or leaving more than 20% of the questions unanswered [8].

Instruments

Data collection in this study was performed using three demographic information tools, the Nurse Clinical Competency Scale by Meretoja et al. [9] and the Nurses’ Alarm Fatigue questionnaire by Torabizadeh et al. [19].

The demographic information questionnaire included age, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, general work history, work experience in the NICU wards, type of work shift, participation in specialized clinical training courses related to newborn care [3], personal and family problems history, history of sedative drug use, history of background problems (effective in fatigue), and participation in clinical competence tests.

To investigate the alarm fatigue of the nurses, Nurses’ Alarm Fatigue questionnaire by Torabizadeh et al., which was prepared in Iran in the special care department, was used. This questionnaire contains 13 items. The 5-point Likert scale for scoring each item includes always (4), mostly (3), sometimes (2), rarely (1) and never (0), which are scored from 0 to 4. Two items of this questionnaire have a reverse score (items 1 and 9), and the range of scores is between 8 and 44. A score of 8 indicates the lowest level of alarm fatigue, and a score of 44 indicates the highest level of alarm fatigue. Torabizadeh et al. reported the reliability of this tool to be 91% [19]. In the present study, the reliability coefficient was determined using Cronbach's alpha method of 0.813.

Nurse clinical competency scale based on the theory from novice to expert Benner, prepared by Meretoja et al. in 2004 [9, 19] and translated and validated into Persian by Bahreini et al. in 2010 [13]. In the study by Meretoja et al., the internal consistency of the tool ranges was reported as favorable (minimum 0.79 and maximum 0.91).

This scale consists of 73 items and 7 subscales, including helping role (7 items, 0-21), teaching-coaching (16 items, 0-48), diagnostic functions (7 items, 0-21), managing situations (8 items, 0-24), therapeutic interventions (10 items, 0-30), ensuring quality (6 items, 0-18) and work role (19 items, 0-57). Nurses rate the use of each skill on a 4-point Likert scale that is scored from 0 to 3 (0 means no use, 1 means very little use, 2 means occasional use, and 3 means frequent use of that skill). The overall score of the tool is between 0-219.

To rank the level of clinical competence, the scores of applying skills, which range from 0-219, were placed on a scale of zero to 100 using linear transformation, in which zero indicates the lowest level of clinical competence and 100 indicates the highest level of clinical competence. Finally, the total score of the instrument was classified into four levels of low (0-25), relatively good (26-50), good (51-75) and very good (76-100). In the present study, the reliability coefficient using Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the whole tool was 0.962, and its ranges (minimum 0.7 and maximum 0.9) were estimated.

Data gathering

After obtaining permission and obtaining the code of ethics, the researcher proceeded to the validity and reliability of three questionnaires. After completing the validity and reliability process, by making the necessary arrangements with the Research Vice-Chancellor of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences as well as the relevant authorities, permission to enter the research environment was obtained. Demographic information tools, Nurses’ Alarm Fatigue questionnaire, and the Nurse Clinical Competency Scale completed by nurses in the form of self-report.

Data analysis

After data extraction, data analysis was performed using SPSS 16 software in two parts; Descriptive statistics (frequency distribution tables, minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (independent T-test, ANOVA test and Pearson correlation coefficient).

Findings

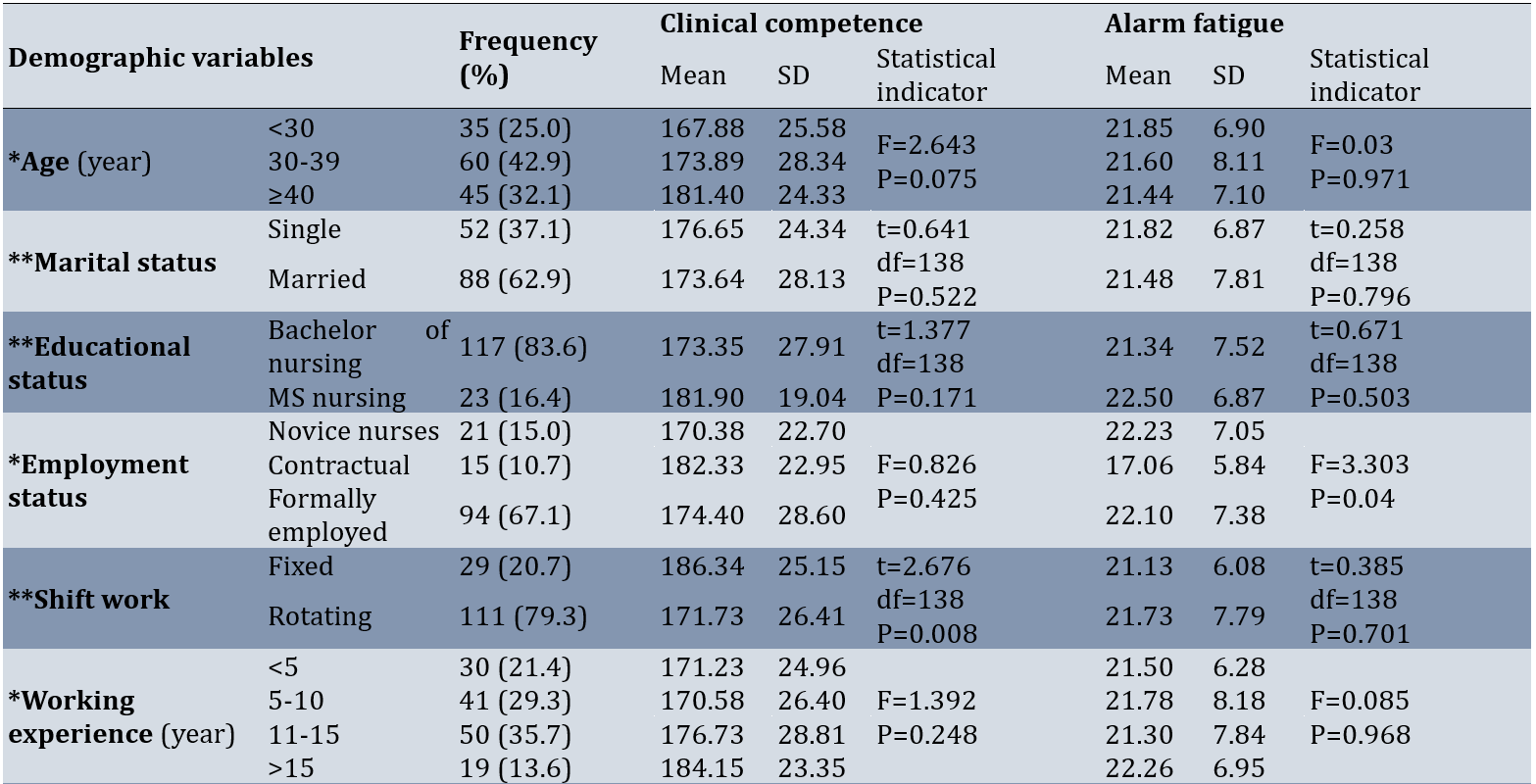

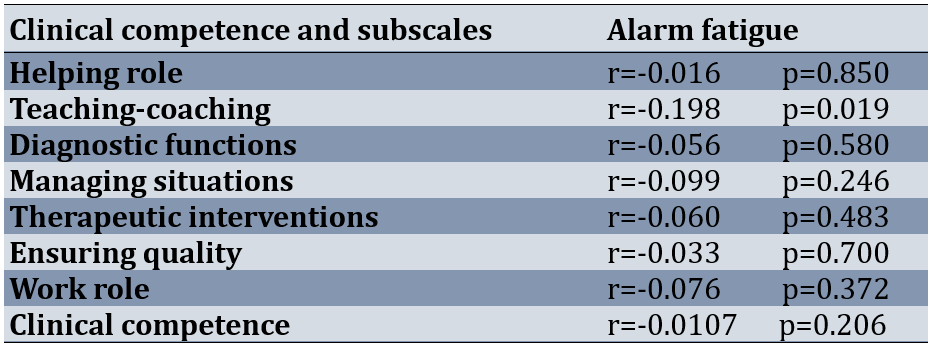

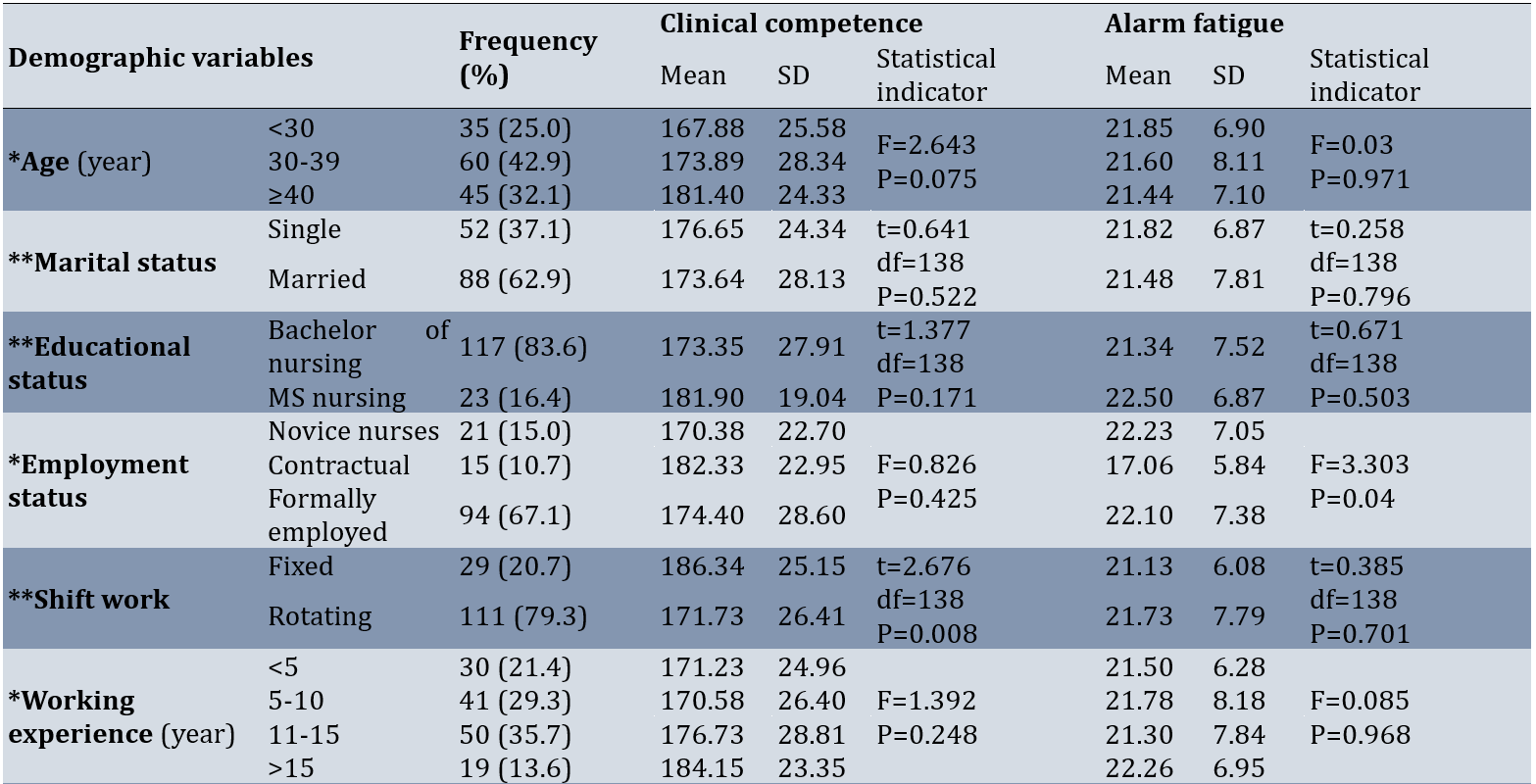

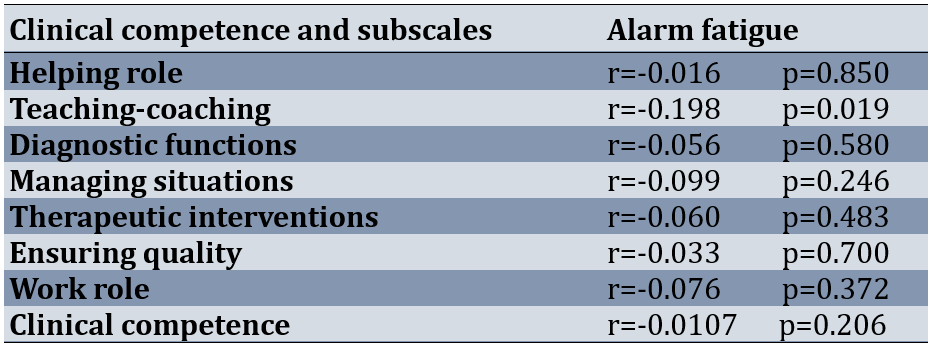

The number of nurses participating in this study was 140. The findings of the study showed that most of the nurses in the study were married (62.9%) and had a bachelor's degree (83.6%). Formally employed (67.1%), and most of the nurses had rotating shifts (79.3%). Most of the nurses had participated in training courses related to neonates (92.1%). A total of 42.1% of nurses had participated in the clinical competency test. Nurses with personal and family problems (19.3%), a history of taking sedatives (8.6%) and background problems (11.4%) were reported. All the nurses were female. The mean age was 35.10±7.56 years old, the average clinical work experience was 11.14±7.30 years, the range was 6 months to 29 years, and the average work experience in the NICU was 7.55±6.34 years, with a range of 6 months to 26 years. Clinical competence had a statistically significant difference with the type of work shift (p=0.008), work experience in the NICU department (p<0.001) and participation in the clinical competence test (p=0.009). Therefore, clinical competence was higher in nurses with a fixed work shift as well as nurses who had a history of participating in the clinical competence test. Tukey's two-by-two comparison also showed that clinical competence was higher in nurses with ten years of work experience and above than nurses with work experience of 5 to 10 years (p<0.001) and this difference was not significant in other levels. Alarm fatigue also had a statistically significant difference with employment status (p=0.04) and personal and family problems (p=0.03). Additionally, Tukey's two-by-two comparison also showed that alarm fatigue in nurses with contract employment status was significantly lower than nurses with official employment (p=0.034; Table 1).

Alarm fatigue was generally obtained with an average of 21.61±7.45 among the nurses studied. Considering that the alarm fatigue score according to the questionnaire used in this study is between 8 and 44, it can be said that the nurses had a fatigue score higher than the average score on the questionnaire, which is equal to 19.

Table 1. Comparison of clinical competence and alarm fatigue scores of nurses based on demographic data

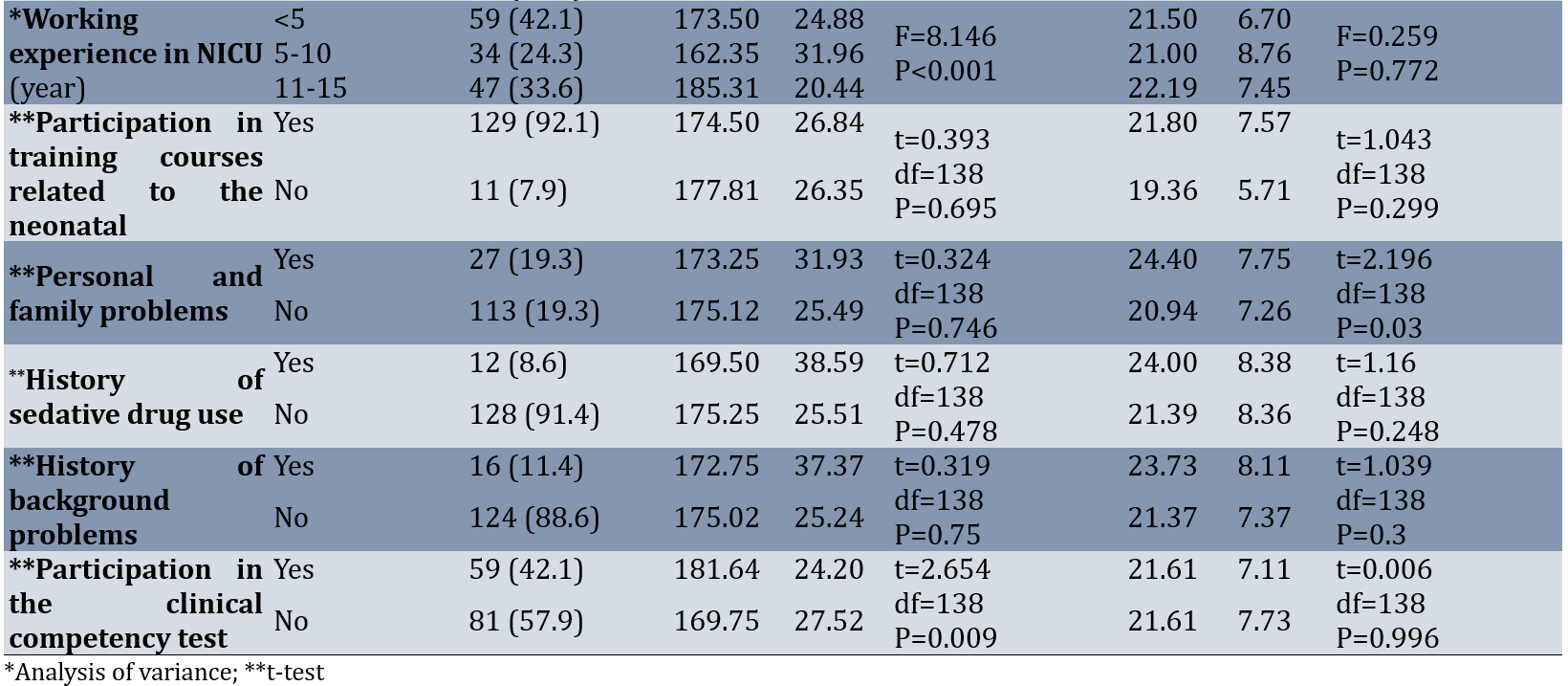

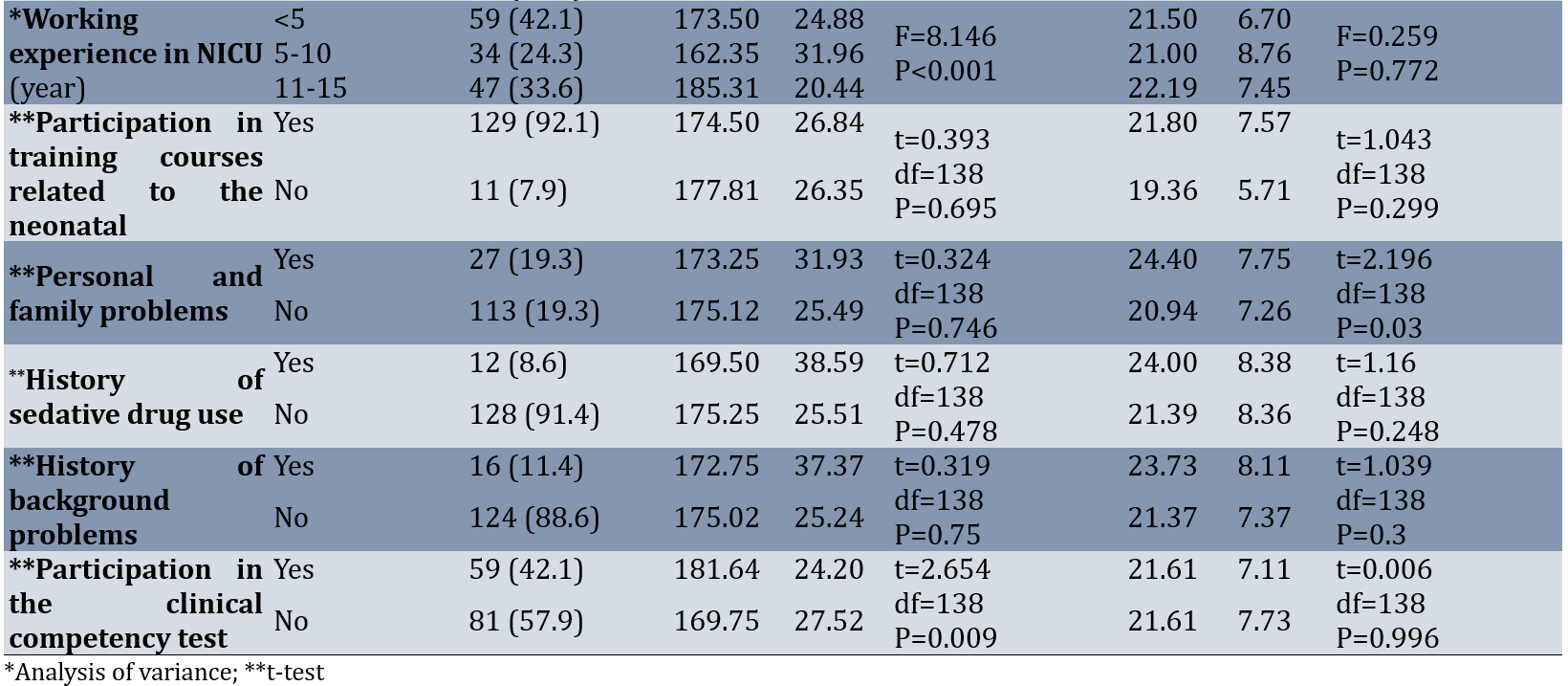

Most of the nurses in the research, that was 75% of them, had very good clinical qualifications. It can also be seen that the clinical competence of most of the nurses studied in all subscales was at a very good level. The average score of clinical competence in the nurses of the study was 174.76±26.74. Additionally, to compare the subscales of clinical competence, the results showed that the average score obtained in the fourth subscale, "managing situations", with an average of 83.72±14.53, was the highest, and in the sixth subscale, "ensuring quality", with an average of 75.31±18.26, had obtained the lowest average score in other subscales of clinical competence (Table 2).

Table 2. Scores of nurse's clinical competence and subscales (Mean±SD)

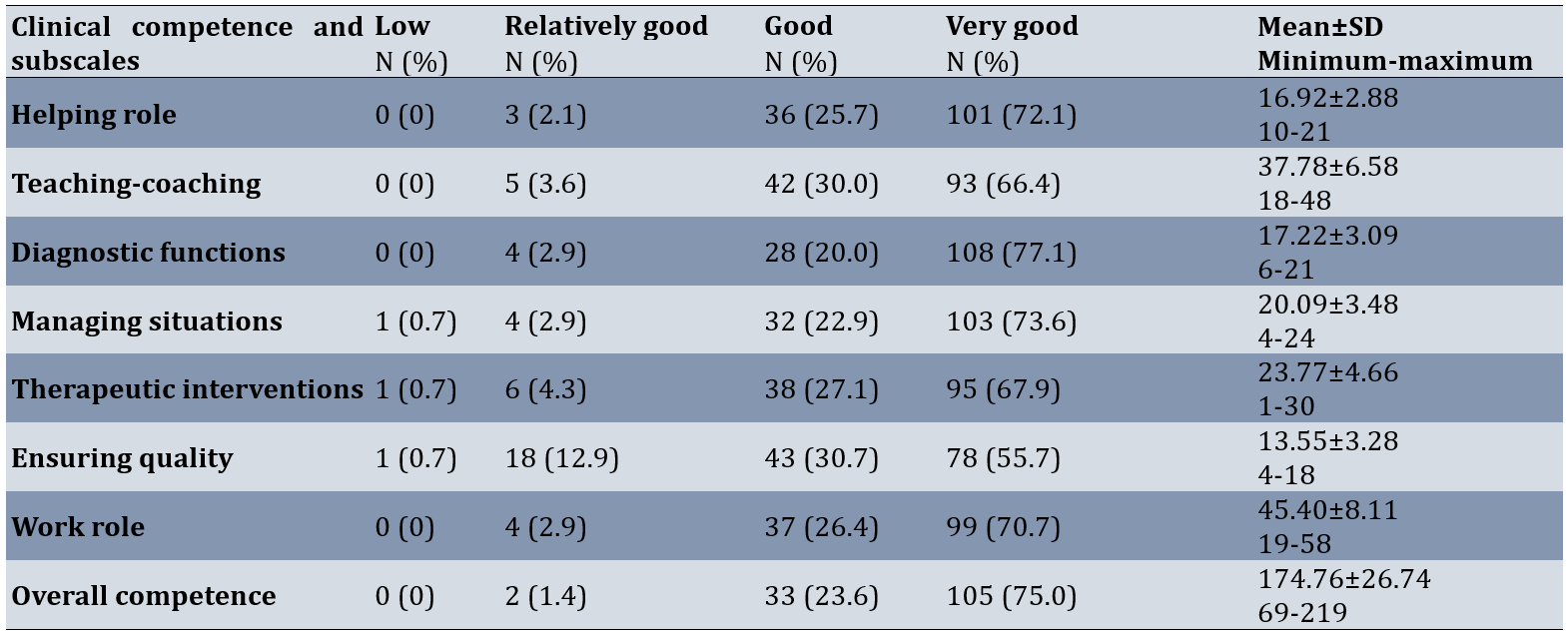

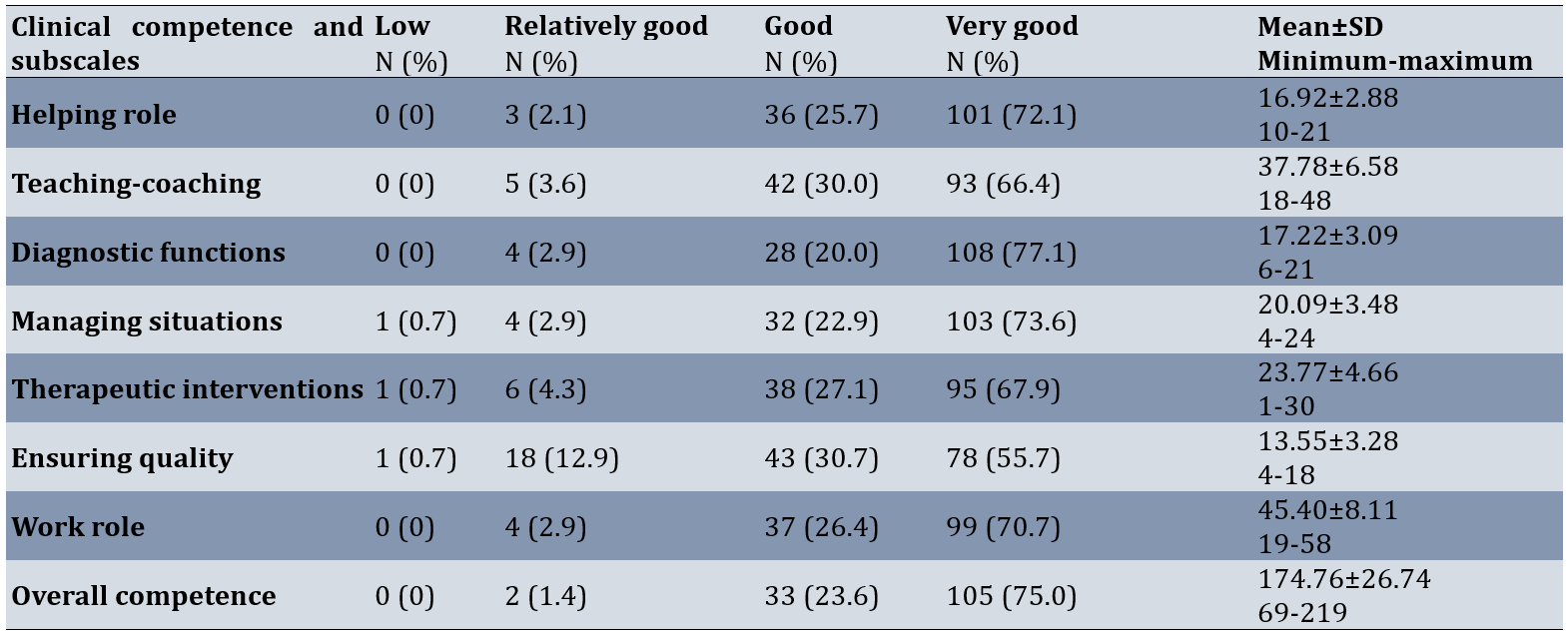

The results showed that alarm fatigue had a statistically significant correlation with clinical competence in the second subscale of teaching-coaching. In other words, with the increase in alarm fatigue, the clinical competence in the teaching-coaching subscale decreaseed (p=0.019). However, there was no correlation between, clinical competence (exception to Teaching-coaching) and alarm fatigue and between each of subscales of clinical competence and alarm fatigue (p>0.05; Table 3).

Table 3. The correlation between alarm fatigue and clinical competence and the subscale scores of nurses

Discussion

The aim of this study aims to assess the relationship between alarm fatigue and clinical competence among neonatal intensive care nurses.

In this study, the average score of alarm fatigue in nurses was above average. The findings of the research in this regard were in line with the results of the research of Sayadi et al.; Therefore, the results show that the average score of alarm fatigue in nurses was higher than average. The researchers concluded that adopting solutions according to the standard guidelines to reduce these alarms, it is necessary to monitor physiological monitoring systems in hospitals [21].

Most of the nurses in the study, had very good clinical qualifications. Additionally, the clinical competence of most of the studied nurses in all subscales was at a very good level. This was although in the study of Mirlashari et al. on the nurses of the neonatal intensive care unit in Iran, more than half of the nurses have an average level of clinical competence [4]. According to the study by Keshavarzi et al., approximately 77% of nurses have good clinical competence [3]. Additionally, in the study of Soroush et al., the clinical competence of nurses is reported at an average level in almost all subscales, and the researchers came to the conclusion that although clinical competence is acquired during the student period, it takes time to achieve clinical competence at a good level [26]. Considering the clinical importance of competence in practice, the clinical competence of nurses should be evaluated objectively and positively, and measures should be taken to improve the application of their clinical competence [8]. Additionally, in order to compare clinical competency subscales, scores based on 0-100, the average score obtained in the fourth subscale of "managing situations" is the highest, and in the sixth subscale of "ensuring quality", the average score is the lowest among other subscales of clinical competence. The findings of the research in this regard are in line with the results of the research of Deldar et al., who show that in the case of clinical competence, the highest average score is related to managing situations and diagnostic functions, and the lowest average is related to ensuring quality [27]. According to the results of the studies conducted by Faraji et al., the highest level of clinical competence is related to the dimension of "managing situations", and the lowest average scores are related to the dimensions of "therapeutic interventions" and "ensuring quality" [8]. Ensuring quality refers to the evaluation of goals and participation in the promotion of nursing care, which is one of the main concerns of nursing managers and health care systems and is taken into account by ensuring the appropriate level of clinical competence in nurses [13].

Increasing the alarm fatigue, the clinical competence of nurses in the "Teaching-Coaching" subscale decreased. The issue of alarm fatigue is considered a priority by the American Special Care Nurses Association, and since 2013, alarm fatigue has been one of the 4 patient safety priorities. In this regard, it is necessary to conduct a survey of medical staff, including nurses and doctors, to hold meetings to determine the limits of alarms and to implement strategies that can reduce the occurrence of false alarms. The training of employees in this regard and appropriate action by them alarm bells should also be considered [21, 28]. Additionally, to improve the quality of newborn care, refresher courses should be held in accordance with the latest changes in the scientific resources of newborn nursing to improve clinical competence.

The clinical competence was higher in nurses with fixed work shifts and nurses who had a history of participating in the clinical competence test. Additionally, there were more nurses with 10 years of work experience and more nurses with 5 to 10 years of work experience. The evidence shows that work experience is one of the influencing factors in the clinical competence of nurses. Therefore, it is expected that with the increase in work experience, clinical competence will also increase [9]. In the study by Keshavarzi et al., there is a statistically significant relationship between nurse shift work and clinical competence, so nurses who worked in the morning shift have more clinical competence [3]. Perhaps attending the morning shift, which is a more educational environment, plays a greater role in improving clinical competence. On the other hand, on the night shift or rotating shift, it is possible that, due to disruption of the biological cycle [29] and more fatigue of the nurse, the clinical competence is affected. On the other hand, one of the limitations of obtaining professional competence in NICU departments is that instead of team and interdisciplinary work, nurses are asked to act above their level of competence and abilities to solve the problems of the neonatal and the family [30, 31]. If the department has a less supportive atmosphere or if the nurse is active more in night shifts or on tour, which has less educational and supportive environment and there is a need for more professional independence, she may have a lower level of professional competence [3].

According to the results of the study, the alarm fatigue in nurses who had personal and family problems was higher than that in other nurses. Additionally, it was significantly lower in nurses with contractual employment status than in nurses with formal employment.

One of the limitations of this study was the use of an instrument based on a self-reporting method that could affect the results of the study, which to minimize it and gain trust, the nurses were assured that this study is research-based and anonymous.

It is appropriate to take measures to strengthen this aspect because most nursing is based on evidence. In different hospitals, the subscales of clinical competence in the nurses of the neonatal and pediatric departments are different. Therefore, it is better to perform more planning to improve education according to the needs of nurses in these hospitals.

Suggestions for future studies include the investigation of ways to improve the dimensions of clinical competence, the investigation of the causes of alarm fatigue and their prevention, and the comparison of two methods of self-evaluation and evaluation by managers in measuring clinical competence

Conclusion

Nurses' overall clinical competence is at a very good level, with alarm fatigue above average. Alarm fatigue significantly correlates with clinical competence in the teaching-coaching subscale, where higher fatigue leads to reduced competence. No correlation is observed between alarm fatigue and other subscales or overall clinical competence. Among subscales, managing situations scored highest, while ensuring quality scored lowest.

Acknowledgments: This article is a part of the thesis research project approved by the Nursing and Midwifery Research Center and the School of Nursing and Midwifery of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services in 2022 with the code of ethics, which was implemented with the support of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services. We hereby thank the Tehran University of Medical Sciences for the support of this project, as well as the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences and the studied hospitals. The researchers thank and appreciate the cooperation of all the nurses and nursing managers who collaborated on this research.

Ethical Permissions: The research protocol has been approved by the joint organizational ethics committee of the nursing and midwifery faculty and the rehabilitation faculty of Tehran and Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences under the number (IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1401.074). The aims of and the rationale for the study, and assurances that the data would be processed anonymously were outlined verbally. Then, the questionnaires, along with the informed consent to participate in the study, were given to the nurses of the neonatal intensive care units in person. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Begjani J (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Bagheri Moheb N (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Haghani Sh (Third Author), Statistical Analyst (20%); Babaei H (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was funded by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences Research Center.

Healthcare is one of the most important areas of sustainable development in human societies and is responsible for the important task of maintaining health. Among healthcare professionals, nurses are the largest group in treatment departments, especially special care departments [1]. Every year, 15 million premature newborns are born worldwide, of which half a million premature newborns are born in the United States of America. Iran is also one of the regions with a high prevalence of premature birth, where approximately 10% of births are premature and have a low birth weight [2]. Caring for sick and hospitalized newborns requires paying attention to the complex, special, critical and changing needs of newborns and having clinical competence, which is the main factor in providing quality care [3] and can improve the quality of nursing care and the survival rate of newborns along with the development of advanced equipment in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) [3, 4].

Competency was introduced as a concept in nursing by Johnson in the late 1960s, and Benner was the first to expand its use in clinical nursing [5, 6]. The WHO has defined clinical competence as a level of performance that represents the effective application of knowledge, skills, and judgment [7]. Clinical competence consists of seven dimensions, which include helping role, teaching-coaching, diagnostic functions, managing situations, therapeutic interventions, ensuring quality and work role [8, 9]. In newborn nursing, clinical competence is defined as having the knowledge, ability and skill to effectively and professionally perform all the care needed by newborns [10].

Inadequate competence of nurses is one of the predisposing factors for the occurrence of clinical errors in care units [11]. The results of some reports indicate that more than 80% of errors leading to secondary injuries of patients were due to negligence or insufficient clinical competence of nurses [12]. In Iran, the results of a study by Bahreini et al. showed that the level of clinical competence of nurses in some subscales, including teaching-coaching and ensuring quality, was unfavorable [13].

On the other hand, in intensive care units, where patients are under care in a critical condition, alarms are everywhere [14, 15]. The majority of patients in the neonatal intensive care unit are preterm newborns with physiologically immature functions who are at risk of serious complications [16]. Responding to alarms accounts for 35% of an intensive care nurse's working time [14]. In previous studies, it was estimated that more than 70% of clinical alarms do not require clinical intervention [16]. However, many alarms are considered false or clinically irrelevant [16, 17], and they even account for 85-99% of all alarms [14, 15, 18]. False alarms reduce response time and nurses' trust in alarms [15, 16], and they also cause disruptions in the planning and efficient performance of nurses and their distraction [19, 20]. This leads to nurses deactivating alarms, failing to respond appropriately, or reducing their volume [21]. Nurses consider these alarms as noisy alarms, causing discomfort, headaches and disrupting patient care, and this situation can cause them to suffer from alarm fatigue in the long run [21, 22]. Alarm fatigue occurs when caregivers are exposed to too many alarms, causing alarm desensitization [23] and delayed or even nonresponse to alarms, which can lead to serious patient harm and unsafe practices. It is known as an important issue of patient safety [15, 16, 24, 25], which was ranked by the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI) as one of the 10 most important technological threats to health (2016-2020) [21]. No similar study was found regarding the relationship between the Alarm Fatigue and Clinical Competence among Neonatal Intensive Care Nurses.

Given the importance of improving nursing care quality in neonatal intensive care units and the lack of studies on clinical competence in these settings, the research team decided to conduct this study. With several years of NICU experience, issues with monitoring alarms and devices were observed, as well as the frustration, headaches, and irritability these alarms cause nurses. This study aims to assess the relationship between alarm fatigue and clinical competence among neonatal intensive care nurses.

Instruments and Methods

Design and participants

This research was a correlational study conducted in neonatal intensive care units in Kermanshah, Iran in 2022-2023. This study included hospitals of Imam Reza, Dr. Mohammad Kermanshahi, Motazedi, Imam Hossein, Hazrat Masoumeh, Hazrat Abulfazl al-Abbas, Bisetun and Hakim. The census sampling method was used and all nurses entered the study (n=153). Of these, 140 people met the inclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria required participants to hold a bachelor's degree or higher in nursing, have at least six months of experience working in a neonatal intensive care unit, be in good physical and mental health as documented in their employment file [3], and have no hearing impairments [21].

Exclusion criteria included a lack of willingness to continue participation in the study, incomplete questionnaire submissions, or leaving more than 20% of the questions unanswered [8].

Instruments

Data collection in this study was performed using three demographic information tools, the Nurse Clinical Competency Scale by Meretoja et al. [9] and the Nurses’ Alarm Fatigue questionnaire by Torabizadeh et al. [19].

The demographic information questionnaire included age, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, general work history, work experience in the NICU wards, type of work shift, participation in specialized clinical training courses related to newborn care [3], personal and family problems history, history of sedative drug use, history of background problems (effective in fatigue), and participation in clinical competence tests.

To investigate the alarm fatigue of the nurses, Nurses’ Alarm Fatigue questionnaire by Torabizadeh et al., which was prepared in Iran in the special care department, was used. This questionnaire contains 13 items. The 5-point Likert scale for scoring each item includes always (4), mostly (3), sometimes (2), rarely (1) and never (0), which are scored from 0 to 4. Two items of this questionnaire have a reverse score (items 1 and 9), and the range of scores is between 8 and 44. A score of 8 indicates the lowest level of alarm fatigue, and a score of 44 indicates the highest level of alarm fatigue. Torabizadeh et al. reported the reliability of this tool to be 91% [19]. In the present study, the reliability coefficient was determined using Cronbach's alpha method of 0.813.

Nurse clinical competency scale based on the theory from novice to expert Benner, prepared by Meretoja et al. in 2004 [9, 19] and translated and validated into Persian by Bahreini et al. in 2010 [13]. In the study by Meretoja et al., the internal consistency of the tool ranges was reported as favorable (minimum 0.79 and maximum 0.91).

This scale consists of 73 items and 7 subscales, including helping role (7 items, 0-21), teaching-coaching (16 items, 0-48), diagnostic functions (7 items, 0-21), managing situations (8 items, 0-24), therapeutic interventions (10 items, 0-30), ensuring quality (6 items, 0-18) and work role (19 items, 0-57). Nurses rate the use of each skill on a 4-point Likert scale that is scored from 0 to 3 (0 means no use, 1 means very little use, 2 means occasional use, and 3 means frequent use of that skill). The overall score of the tool is between 0-219.

To rank the level of clinical competence, the scores of applying skills, which range from 0-219, were placed on a scale of zero to 100 using linear transformation, in which zero indicates the lowest level of clinical competence and 100 indicates the highest level of clinical competence. Finally, the total score of the instrument was classified into four levels of low (0-25), relatively good (26-50), good (51-75) and very good (76-100). In the present study, the reliability coefficient using Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the whole tool was 0.962, and its ranges (minimum 0.7 and maximum 0.9) were estimated.

Data gathering

After obtaining permission and obtaining the code of ethics, the researcher proceeded to the validity and reliability of three questionnaires. After completing the validity and reliability process, by making the necessary arrangements with the Research Vice-Chancellor of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences as well as the relevant authorities, permission to enter the research environment was obtained. Demographic information tools, Nurses’ Alarm Fatigue questionnaire, and the Nurse Clinical Competency Scale completed by nurses in the form of self-report.

Data analysis

After data extraction, data analysis was performed using SPSS 16 software in two parts; Descriptive statistics (frequency distribution tables, minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (independent T-test, ANOVA test and Pearson correlation coefficient).

Findings

The number of nurses participating in this study was 140. The findings of the study showed that most of the nurses in the study were married (62.9%) and had a bachelor's degree (83.6%). Formally employed (67.1%), and most of the nurses had rotating shifts (79.3%). Most of the nurses had participated in training courses related to neonates (92.1%). A total of 42.1% of nurses had participated in the clinical competency test. Nurses with personal and family problems (19.3%), a history of taking sedatives (8.6%) and background problems (11.4%) were reported. All the nurses were female. The mean age was 35.10±7.56 years old, the average clinical work experience was 11.14±7.30 years, the range was 6 months to 29 years, and the average work experience in the NICU was 7.55±6.34 years, with a range of 6 months to 26 years. Clinical competence had a statistically significant difference with the type of work shift (p=0.008), work experience in the NICU department (p<0.001) and participation in the clinical competence test (p=0.009). Therefore, clinical competence was higher in nurses with a fixed work shift as well as nurses who had a history of participating in the clinical competence test. Tukey's two-by-two comparison also showed that clinical competence was higher in nurses with ten years of work experience and above than nurses with work experience of 5 to 10 years (p<0.001) and this difference was not significant in other levels. Alarm fatigue also had a statistically significant difference with employment status (p=0.04) and personal and family problems (p=0.03). Additionally, Tukey's two-by-two comparison also showed that alarm fatigue in nurses with contract employment status was significantly lower than nurses with official employment (p=0.034; Table 1).

Alarm fatigue was generally obtained with an average of 21.61±7.45 among the nurses studied. Considering that the alarm fatigue score according to the questionnaire used in this study is between 8 and 44, it can be said that the nurses had a fatigue score higher than the average score on the questionnaire, which is equal to 19.

Table 1. Comparison of clinical competence and alarm fatigue scores of nurses based on demographic data

Most of the nurses in the research, that was 75% of them, had very good clinical qualifications. It can also be seen that the clinical competence of most of the nurses studied in all subscales was at a very good level. The average score of clinical competence in the nurses of the study was 174.76±26.74. Additionally, to compare the subscales of clinical competence, the results showed that the average score obtained in the fourth subscale, "managing situations", with an average of 83.72±14.53, was the highest, and in the sixth subscale, "ensuring quality", with an average of 75.31±18.26, had obtained the lowest average score in other subscales of clinical competence (Table 2).

Table 2. Scores of nurse's clinical competence and subscales (Mean±SD)

The results showed that alarm fatigue had a statistically significant correlation with clinical competence in the second subscale of teaching-coaching. In other words, with the increase in alarm fatigue, the clinical competence in the teaching-coaching subscale decreaseed (p=0.019). However, there was no correlation between, clinical competence (exception to Teaching-coaching) and alarm fatigue and between each of subscales of clinical competence and alarm fatigue (p>0.05; Table 3).

Table 3. The correlation between alarm fatigue and clinical competence and the subscale scores of nurses

Discussion

The aim of this study aims to assess the relationship between alarm fatigue and clinical competence among neonatal intensive care nurses.

In this study, the average score of alarm fatigue in nurses was above average. The findings of the research in this regard were in line with the results of the research of Sayadi et al.; Therefore, the results show that the average score of alarm fatigue in nurses was higher than average. The researchers concluded that adopting solutions according to the standard guidelines to reduce these alarms, it is necessary to monitor physiological monitoring systems in hospitals [21].

Most of the nurses in the study, had very good clinical qualifications. Additionally, the clinical competence of most of the studied nurses in all subscales was at a very good level. This was although in the study of Mirlashari et al. on the nurses of the neonatal intensive care unit in Iran, more than half of the nurses have an average level of clinical competence [4]. According to the study by Keshavarzi et al., approximately 77% of nurses have good clinical competence [3]. Additionally, in the study of Soroush et al., the clinical competence of nurses is reported at an average level in almost all subscales, and the researchers came to the conclusion that although clinical competence is acquired during the student period, it takes time to achieve clinical competence at a good level [26]. Considering the clinical importance of competence in practice, the clinical competence of nurses should be evaluated objectively and positively, and measures should be taken to improve the application of their clinical competence [8]. Additionally, in order to compare clinical competency subscales, scores based on 0-100, the average score obtained in the fourth subscale of "managing situations" is the highest, and in the sixth subscale of "ensuring quality", the average score is the lowest among other subscales of clinical competence. The findings of the research in this regard are in line with the results of the research of Deldar et al., who show that in the case of clinical competence, the highest average score is related to managing situations and diagnostic functions, and the lowest average is related to ensuring quality [27]. According to the results of the studies conducted by Faraji et al., the highest level of clinical competence is related to the dimension of "managing situations", and the lowest average scores are related to the dimensions of "therapeutic interventions" and "ensuring quality" [8]. Ensuring quality refers to the evaluation of goals and participation in the promotion of nursing care, which is one of the main concerns of nursing managers and health care systems and is taken into account by ensuring the appropriate level of clinical competence in nurses [13].

Increasing the alarm fatigue, the clinical competence of nurses in the "Teaching-Coaching" subscale decreased. The issue of alarm fatigue is considered a priority by the American Special Care Nurses Association, and since 2013, alarm fatigue has been one of the 4 patient safety priorities. In this regard, it is necessary to conduct a survey of medical staff, including nurses and doctors, to hold meetings to determine the limits of alarms and to implement strategies that can reduce the occurrence of false alarms. The training of employees in this regard and appropriate action by them alarm bells should also be considered [21, 28]. Additionally, to improve the quality of newborn care, refresher courses should be held in accordance with the latest changes in the scientific resources of newborn nursing to improve clinical competence.

The clinical competence was higher in nurses with fixed work shifts and nurses who had a history of participating in the clinical competence test. Additionally, there were more nurses with 10 years of work experience and more nurses with 5 to 10 years of work experience. The evidence shows that work experience is one of the influencing factors in the clinical competence of nurses. Therefore, it is expected that with the increase in work experience, clinical competence will also increase [9]. In the study by Keshavarzi et al., there is a statistically significant relationship between nurse shift work and clinical competence, so nurses who worked in the morning shift have more clinical competence [3]. Perhaps attending the morning shift, which is a more educational environment, plays a greater role in improving clinical competence. On the other hand, on the night shift or rotating shift, it is possible that, due to disruption of the biological cycle [29] and more fatigue of the nurse, the clinical competence is affected. On the other hand, one of the limitations of obtaining professional competence in NICU departments is that instead of team and interdisciplinary work, nurses are asked to act above their level of competence and abilities to solve the problems of the neonatal and the family [30, 31]. If the department has a less supportive atmosphere or if the nurse is active more in night shifts or on tour, which has less educational and supportive environment and there is a need for more professional independence, she may have a lower level of professional competence [3].

According to the results of the study, the alarm fatigue in nurses who had personal and family problems was higher than that in other nurses. Additionally, it was significantly lower in nurses with contractual employment status than in nurses with formal employment.

One of the limitations of this study was the use of an instrument based on a self-reporting method that could affect the results of the study, which to minimize it and gain trust, the nurses were assured that this study is research-based and anonymous.

It is appropriate to take measures to strengthen this aspect because most nursing is based on evidence. In different hospitals, the subscales of clinical competence in the nurses of the neonatal and pediatric departments are different. Therefore, it is better to perform more planning to improve education according to the needs of nurses in these hospitals.

Suggestions for future studies include the investigation of ways to improve the dimensions of clinical competence, the investigation of the causes of alarm fatigue and their prevention, and the comparison of two methods of self-evaluation and evaluation by managers in measuring clinical competence

Conclusion

Nurses' overall clinical competence is at a very good level, with alarm fatigue above average. Alarm fatigue significantly correlates with clinical competence in the teaching-coaching subscale, where higher fatigue leads to reduced competence. No correlation is observed between alarm fatigue and other subscales or overall clinical competence. Among subscales, managing situations scored highest, while ensuring quality scored lowest.

Acknowledgments: This article is a part of the thesis research project approved by the Nursing and Midwifery Research Center and the School of Nursing and Midwifery of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services in 2022 with the code of ethics, which was implemented with the support of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services. We hereby thank the Tehran University of Medical Sciences for the support of this project, as well as the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences and the studied hospitals. The researchers thank and appreciate the cooperation of all the nurses and nursing managers who collaborated on this research.

Ethical Permissions: The research protocol has been approved by the joint organizational ethics committee of the nursing and midwifery faculty and the rehabilitation faculty of Tehran and Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences under the number (IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1401.074). The aims of and the rationale for the study, and assurances that the data would be processed anonymously were outlined verbally. Then, the questionnaires, along with the informed consent to participate in the study, were given to the nurses of the neonatal intensive care units in person. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Begjani J (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Bagheri Moheb N (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Haghani Sh (Third Author), Statistical Analyst (20%); Babaei H (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was funded by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences Research Center.

Keywords:

Nurses [MeSH], Alert Fatigue [MeSH], Health Personnel [MeSH], Clinical Competence [MeSH], Intensive Care Units [MeSH], Neonate [MeSH]

References

1. Fotohi P, Olyaie N, Salehi K. The dimensions of clinical competence of nurses working in critical care units and their relation with the underlying factors. Q J Nurs Manag. 2019;8(2):1-9. [Persian] [Link]

2. Hoseinpour S, Borimnejad L, Rasooli M, Hardani AK, Alhani F. The effect of implementing a family-centered empowerment model on the quality of life of parents of premature infants admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit. Iran J Nurs. 2022;34(134):2-17. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/ijn.34.6.1]

3. Keshavarzi N, Nourian M, Oujian P, Alaee Karahroudi F. Clinical competence and its relationship with job stress among neonatal intensive care unit nurses: A descriptive study. Nurs Midwifery J. 2021;19(7):527-38. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.52547/unmf.19.7.2]

4. Mirlashari J, Qommi R, Nariman S, Bahrani N, Begjani J. Clinical competence and its related factors of nurses in neonatal intensive care units. J Caring Sci. 2016;5(4):317-24. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/jcs.2016.033]

5. Johnson DE. Competence in practice: Technical and professional. Nurs Outlook. 1966;14(10):30-3. [Link]

6. Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82(3):402-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00000446-198282030-00004]

7. WHO. Responding to community spread of COVID-19. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

8. Faraji A, Karimi M, Azizi SM, Janatolmakan M, Khatony A. Evaluation of clinical competence and its related factors among ICU nurses in Kermanshah-Iran: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6(4):421-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.09.007]

9. Meretoja R, Isoaho H, Leino‐Kilpi H. Nurse competence scale: Development and psychometric testing. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(2):124-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03071.x]

10. Dudding KM, Bordelon C, Sanders AN, Shorten A, Wood T, Watts P. Improving quality in neonatal care through competency-based simulation. Neonatal Netw. 2022;41(3):159-67. [Link] [DOI:10.1891/NN-2021-0014]

11. Tai C, Chen D, Zhang Y, Teng Y, Li X, Ma C. Exploring the influencing factors of patient safety competency of clinical nurses: A cross-sectional study based on latent profile analysis. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):154. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12912-024-01817-z]

12. Atashzadeh‐Shoorideh F, Shirinabadi Farahani A, Pishgooie AH, Babaie M, Hadi N, Beheshti M, et al. A comparative study of patient safety in the intensive care units. Nurs Open. 2022;9(5):2381-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/nop2.1252]

13. Bahreini M, Shahamat S, Hayatdavoudi P, Mirzaei M. Comparison of the clinical competence of nurses working in two university hospitals in Iran. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13(3):282-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00611.x]

14. Lewandowska K, Weisbrot M, Cieloszyk A, Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska W, Krupa S, Ozga D. Impact of alarm fatigue on the work of nurses in an intensive care environment-A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8409. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17228409]

15. Seifert M, Tola DH, Thompson J, McGugan L, Smallheer B. Effect of bundle set interventions on physiologic alarms and alarm fatigue in an intensive care unit: A quality improvement project. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;67:103098. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103098]

16. Varisco G, Van De Mortel H, Cabrera‐Quiros L, Atallah L, Hueske‐Kraus D, Long X, et al. Optimisation of clinical workflow and monitor settings safely reduces alarms in the NICU. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(4):1141-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/apa.15615]

17. Huo J, Wung S, Roveda J, Li A. Reducing false alarms in intensive care units: A scoping review. Explor Res Hypothesis Med. 2023;8(1):57-64. [Link]

18. Ali Al-Quraan H, Eid A, Alloubani A. Assessment of alarm fatigue risk among oncology nurses in Jordan. SAGE Open Nurs. 2023;9:23779608231170730. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/23779608231170730]

19. Torabizadeh C, Yousefinya A, Zand F, Rakhshan M, Fararooei M. A nurses' alarm fatigue questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties. J Clin Monit Comput. 2017;31(6):1305-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10877-016-9958-x]

20. Yousefinya A, Torabizadeh C, Zand F, Rakhshan M, Fararooei M. Effectiveness of application of a manual for improvement of alarms management by nurses in Intensive Care Units. Invest Educ Enferm. 2021;39(2):e11. [Link] [DOI:10.17533/udea.iee.v39n2e11]

21. Sayadi L, Seylani K, Akbari Sarruei M, Faghihzadeh E. Physiologic monitor alarm status and nurses' alarm fatigue in coronary care units. HAYAT. 2019;25(3):342-55. [Persian] [Link]

22. Johnson KR, Hagadorn JI, Sink DW. Alarm safety and alarm fatigue. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44(3):713-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.clp.2017.05.005]

23. Jämsä JO, Uutela KH, Tapper AM, Lehtonen L. Clinical alarms and alarm fatigue in a University Hospital Emergency Department-A retrospective data analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65(7):979-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/aas.13824]

24. Ding S, Huang X, Sun R, Yang L, Yang X, Li X, et al. The relationship between alarm fatigue and burnout among critical care nurses: A cross‐sectional study. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28(6):940-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12899]

25. Gündoğan G, Erdağı Oral S. The effects of alarm fatigue on the tendency to make medical errors in nurses working in intensive care units. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28(6):996-1003. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12969]

26. Soroush F, Zargham-Boroujeni A, Namnabati M. The relationship between nurses' clinical competence and burnout in neonatal intensive care units. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2016;21(4):424-9. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1735-9066.185596]

27. Deldar M, Bahreini M, Ravanipour M, Bagherzadeh R. The relationship of nurses' clinical competence and communication skills with parents' anxiety during neonates and children's hospitalization. Q J Nurs Manag. 2020;9(2):42-55. [Persian] [Link]

28. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: A patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):378-86. [Link] [DOI:10.4037/NCI.0b013e3182a903f9]

29. Queen-Lomas M. Night shift acute care nurse narratives: Exploring collaborative solutions to reduce burnout, increase morale and engagement, and improve retention [dissertation]. Hattiesburg: The University of Southern Mississippi; 2024. [Link]

30. Skorobogatova N, Žemaitienė N, Šmigelskas K, Tamelienė R, Markūnienė E, Stonienė D. Limits of professional competency in nurses working in Nicu. Open Med. 2018;13(1):410-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1515/med-2018-0060]

31. Franck LS, Bisgaard R, Cormier DM, Hutchison J, Moore D, Gay C, et al. Improving family-centered care for infants in neonatal intensive care units: Recommendations from frontline healthcare professionals. Adv Neonatal Care. 2022;22(1):79-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/ANC.0000000000000854]