Volume 5, Issue 4 (2024)

J Clinic Care Skill 2024, 5(4): 197-205 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: R.YUMS.REC.1403.032

History

Received: 2024/11/19 | Accepted: 2024/12/21 | Published: 2024/12/25

Received: 2024/11/19 | Accepted: 2024/12/21 | Published: 2024/12/25

How to cite this article

Shabanikordsholi Z, Safari M, Parvizi S, Shabanikordsholi P. The Barriers of Mother and Newborn Skin-to-Skin Contact at Birth in the Midwives Viewpoint. J Clinic Care Skill 2024; 5 (4) :197-205

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-298-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-298-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- “Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine” and “Student Research Committee”, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

3- Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Member, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

4- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

2- Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

3- Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Member, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

4- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (1480 Views)

Introduction

The first hour after birth is a unique period referred to as the “sensitive period,” during which the newborn exhibits elevated levels of catecholamines that keep it alert. Simultaneously, the maternal hormonal response, involving oxytocin and prolactin, fosters mother-infant bonding [1, 2]. Separating the infant from the mother during this time, even briefly, can adversely impact the infant's physical and mental health and survival [1, 3].

According to John Bowlby's attachment theory, mothers who are available to their children from the beginning and respond to their needs foster a sense of peace and security, encouraging the child to confidently explore their surroundings [4]. Adequate skin-to-skin contact within the first hour of life promotes this sense of security in the infant. Conversely, premature separation may disrupt the mother-infant bond, diminish emotional responsiveness between them, and negatively affect maternal behavior [5].

Skin-to-skin contact at birth is a recognized standard of care for healthy newborns. As a safe and cost-effective intervention, it reduces maternal and infant mortality, particularly in developing countries, yet its acceptance and implementation remain limited [6, 7]. When skin-to-skin contact is initiated immediately after birth, the infant is able to seek out the breast and begin breastfeeding—a natural instinctive behavior referred to as the "breast crawl" [8].

The infant typically exhibits this instinctive behavior within 30 to 60 minutes, although in some cases, breastfeeding may take up to an hour. Even in such instances, skin-to-skin contact remains highly beneficial and valuable [9]. Placing the naked infant on the mother's bare abdomen or chest immediately after birth helps prevent hypothermia and hypoglycemia, reduces the risk of neonatal sepsis, and stabilizes the infant's heart rate and breathing [10, 11]. It also improves heart and lung function, facilitates the transfer of beneficial bacteria, reduces infant crying, alleviates pain during medical procedures, strengthens the mother-infant bond, and aids the infant’s adaptation to the external environment [12].

One of the most critical benefits of skin-to-skin contact is preventing hypothermia in the newborn. However, in many hospitals, instead of prioritizing and promoting skin-to-skin contact as a means of preventing hypothermia, other measures are emphasized. These include the use of warmers, encouraging early breastfeeding, wrapping the baby in a warm towel, turning on room heaters, and delaying the baby’s first bath [13, 14].

For mothers, the benefits of skin-to-skin contact include a shorter third stage of labor with earlier placental separation and expulsion, reduced postpartum bleeding, and a decreased need for postpartum analgesia [15, 16]. Additionally, skin-to-skin contact lowers maternal anxiety by regulating cortisol production, enhances maternal bonding and caregiving behaviors, and reduces symptoms of postpartum depression [17].

According to the 2021 national guidelines, during skin-to-skin contact, the baby's health, breathing, and body temperature are monitored. Even if an episiotomy or perineal repair is performed, skin-to-skin contact is maintained throughout the procedure [18]. However, non-urgent care, such as vitamin K injections, footprinting, vaccinations, weighing, and other measurements or procedures, is postponed until after skin-to-skin contact has been completed [9].

The implementation and definition of skin-to-skin contact vary in both practice and research studies, leading to inconsistencies [19]. The duration of skin-to-skin contact differs worldwide. For example, a French study reported an average duration of approximately 90 minutes [20]. In contrast, a 2013 cross-sectional study in Iran found that 98% of midwives conducted skin-to-skin contact for a minimum of 2 minutes and a maximum of 4 minutes [9]. Another study from 2013 reported that the adherence rate to skin-to-skin contact guidelines was 53% [21].

Potential barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact include concerns about hypothermia in the baby, the need for immediate examination or weighing, maternal stitches, the baby’s need for bathing, crowded delivery rooms, insufficient staff to care for the mother and baby, the baby’s lack of alertness or fatigue, and the mother’s unwillingness to participate [9].

Other barriers include a shortage of personnel, time constraints, challenges in determining whether the mother and baby are eligible for skin-to-skin contact or maternal hugging, lack of adequate and continuous training, an inappropriate environment for conducting the contact process, and insufficient systematic supervision by department managers [22, 23]. Allen et al. identified additional barriers, including the baby's restlessness and fear of falling, mothers wearing inappropriate clothing that restricts access to the bare chest, and unnecessary interventions by birth attendants, such as weighing and washing the baby, as primary reasons for not implementing skin-to-skin contact within the first hour of birth [24].

Mukherjee et al. reported that the most common reason for not performing skin-to-skin contact is a lack of awareness about its importance in infant care [25]. A qualitative study by Ebrahimi et al., involving interviews with delivery room managers, specialists, and staff, highlighted that inadequate training, lack of motivation, and insufficient managerial support, such as effective supervision and rewards, are significant obstacles to implementing skin-to-skin contact in Iran [26].

Given the poor implementation of national guidelines for this care in many hospitals, including those targeted by our study, and the absence of a comprehensive study investigating the perspectives of midwives—who play a critical role in maternal and newborn care at birth—it is clear that further research is needed. This study aimed to identify and address the barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact guidelines between mothers and newborns at birth, from the perspective of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj, Iran.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in 2024 and involved 88 midwives working in two hospitals in Yasuj, including Shahid Beheshti and Imam Sajjad.

The inclusion criteria required midwives to be working in the maternity, postpartum, gynecological surgery, neonatal, or administrative wards of the hospitals. Participants were also required to have at least one year of experience working in the maternity ward or be faculty members responsible for training students in these wards. Sampling was conducted using total population sampling. One midwife was excluded from the study due to her unwillingness to participate.

The data collection tool consisted of a researcher-designed questionnaire with two parts. The first part focused on the demographic and occupational characteristics of the midwives (12 questions), while the second part included questions related to the implementation of skin-to-skin contact and its methods (two questions). Additionally, the second part included questions addressing seven areas of barriers to skin-to-skin contact from the midwives' perspective. These areas were: barriers related to midwives' awareness and knowledge (14 questions), structural and environmental barriers (six questions), human resource barriers (six questions), content barriers (five questions), barriers to maternal and newborn safety (five questions), cultural barriers and maternal adaptation (nine questions), and management and supervisory barriers (seven questions). These questions were developed based on the study's objectives. The validity of the questionnaire was assessed using the content validity index (CVI). To calculate the CVI, seven faculty members, and professors from the midwifery department evaluated the relevance of each item in the seven areas on a four-point scale: not relevant (one), needs major revision (two), relevant but needs revision (three), and completely relevant (four). The number of evaluators who selected options three and four for each item was divided by the total number of evaluators. Items with a CVI score of less than 0.7 were deleted, scores between 0.7 and 0.79 were revised, and scores greater than 0.79 were considered acceptable. As a result, one question with a score below 0.7 was removed.

To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, the test-retest method was employed. The questionnaire was completed by seven midwives and then re-administered one week later. The correlation coefficient of the scores obtained from the two instances was calculated, yielding a value of 0.95, indicating high reliability.

After receiving approval from the Student Research Committee of the university and the Research Council (ethics code: IR.YUMS.REC.1403.032) and obtaining permission from the officials of Imam Sajjad and Shohada Gomnam hospitals, we visited the respective hospitals. After explaining the objectives of the project to the midwives and obtaining their informed consent, we conducted interviews with each midwife to complete the relevant questionnaires.

After the questionnaires were completed by the participating midwives, a score ranging from zero to two was assigned to determine the midwives' overall view of the barriers in the seven areas of the questionnaire. Each question was scored based on the number of response options (e.g., yes, no, to some extent). For the knowledge and awareness dimension, questions that measured knowledge and awareness were assigned a score of two for the correct option and zero for the incorrect option. For the other dimensions, the negative form of the questions was used in the scoring. The option that confirmed the obstacle received a score of two, the intermediate option received a score of one, and the option that did not confirm the obstacle received a score of zero.

Thus, a maximum of 30 points was assigned to the knowledge and awareness dimension, a maximum of 12 points each for the human resource and environmental/structural barriers dimensions, a maximum of 10 points each for the content barriers and barriers to maternal and newborn safety dimensions, a maximum of 18 points for the cultural barriers and maternal adaptation dimension, and a maximum of 14 points for the management and supervision dimension. A total of 104 points were possible across all dimensions. A score of 50% or more of the total score in each domain was considered confirmation of the midwives' view of the barrier, while a score below 50% was considered non-confirmation.

Data analysis was carried out using descriptive statistical indices, including absolute and relative frequency tables, measures of central tendency, and measures of dispersion (mean, standard deviation, etc.), utilizing SPSS version 16 software.

Findings

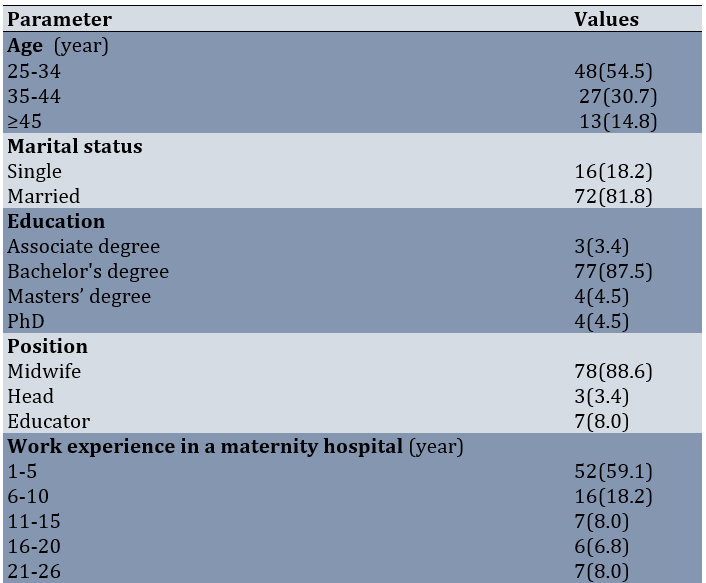

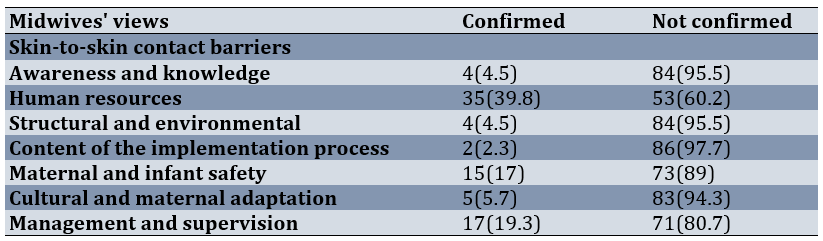

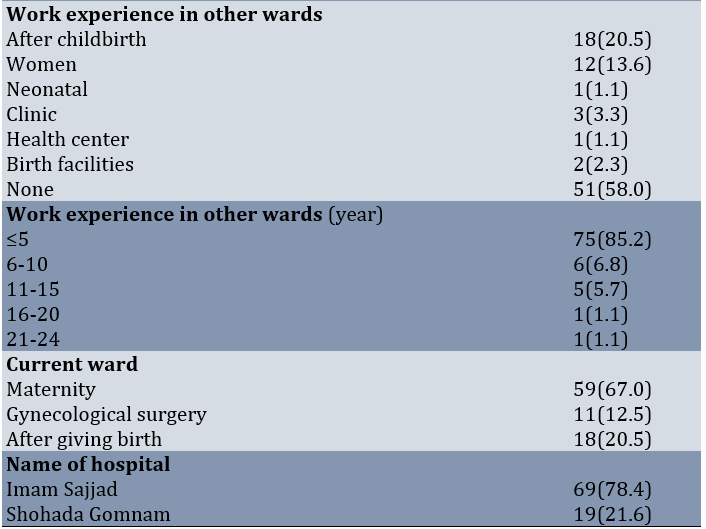

A total of 88 midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj participated in this study. Of these, 69 (78.4%) were employed at Imam Sajjad Hospital and 19 (21.6%) were employed at Shohada Gomnam Hospital. The minimum age was 25 years, and the maximum age was 59 years, with a mean age of 48.2 ± 35.91. The minimum length of work experience in the maternity ward was one year, and the maximum was 26 years, with a mean of 6.7 ± 6.86 years. The minimum length of work experience in other departments was zero, and the maximum was 24 years, with a mean of 4.2 ± 2.34 years. From the perspective of all midwives, skin-to-skin contact was routinely performed in their hospital; however, only 40 (45.5%) believed that this care was performed according to the guidelines, while 48 (54.5%) believed that skin-to-skin contact was not performed according to the guidelines in their hospital (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic and occupational characteristics of midwives working in Yasuj hospitals

The highest frequency of midwives participating in the study was in the age group of 25 to 34 years, and the lowest frequency was in the age group of 45 years and above. The highest frequency was observed in married individuals, and in terms of education, the highest frequency was for those holding a bachelor's degree. The highest frequency of work experience was in the one to five years range, while the lowest frequency was in the 16 to 20 years range. Most of the midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city were currently working in the maternity ward, and the lowest frequency of their workplace was in the gynecological surgery ward. The highest frequency of midwives working in the maternity ward was observed at Imam Sajjad Hospital.

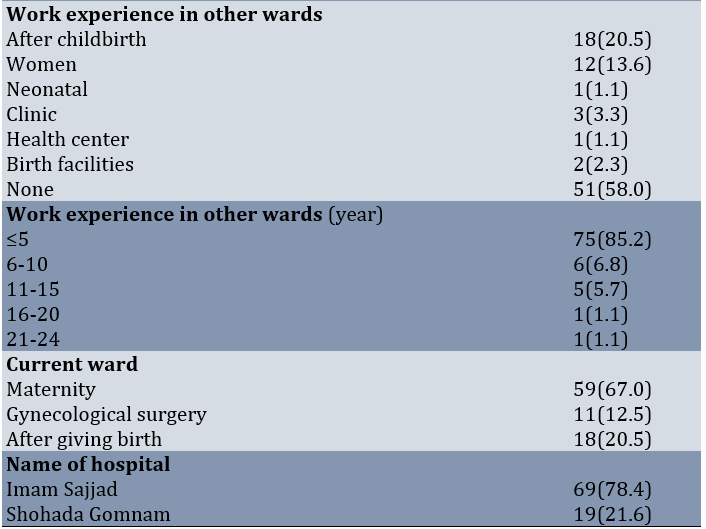

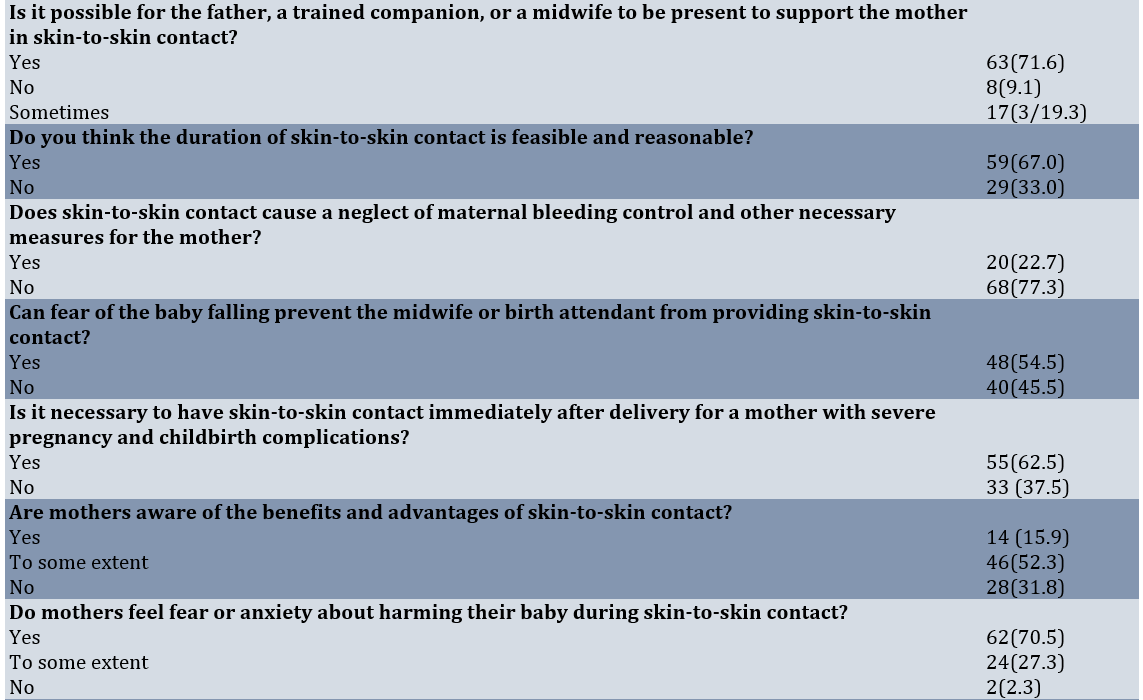

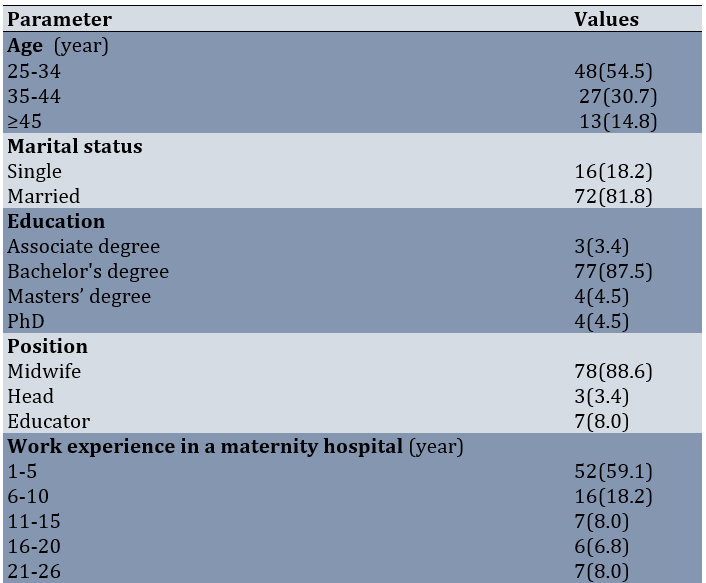

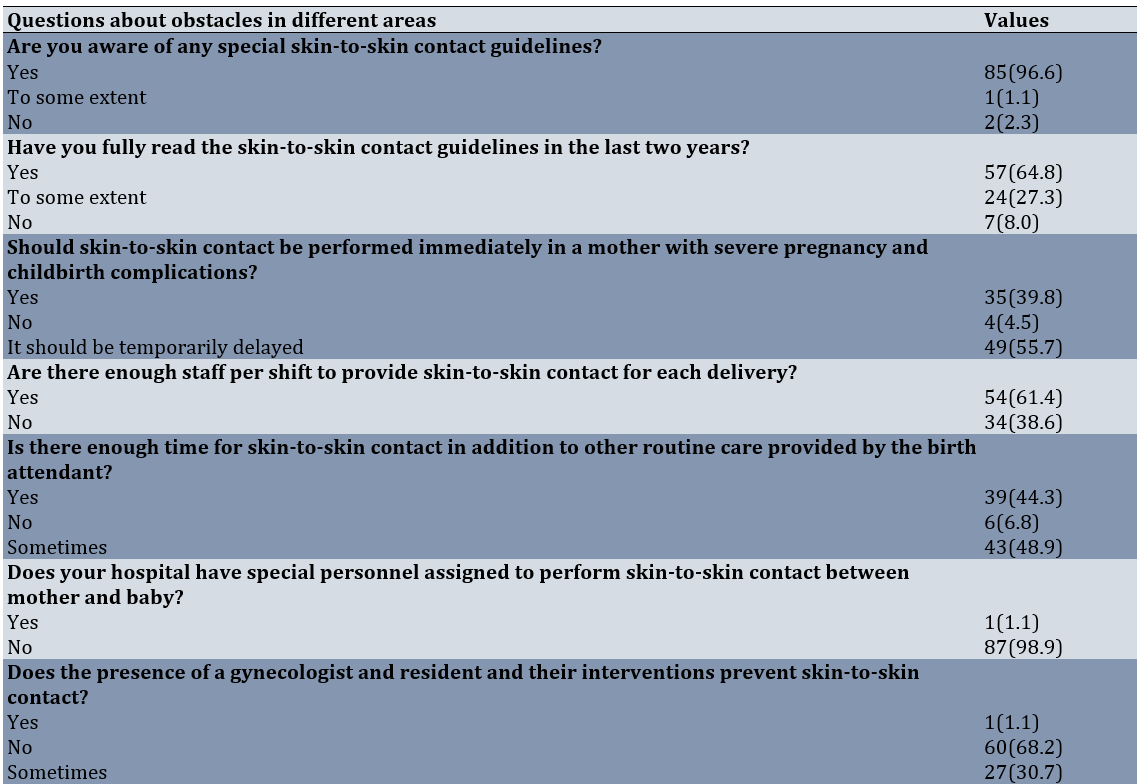

Questions 1-3 relate to knowledge barriers, 4-7 to human resource barriers, 8 to structural and environmental barriers, 9 to content barriers in the implementation process, 10-12 to maternal and newborn safety barriers, 13-15 to cultural barriers and maternal adaptation, and 16-19 to management and supervision barriers. The most common obstacles were related to management and supervision and human resources, while the least common obstacles were related to structural, environmental, and content barriers in the implementation process (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of views of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city regarding the most common obstacles in different areas of implementing skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn at birth

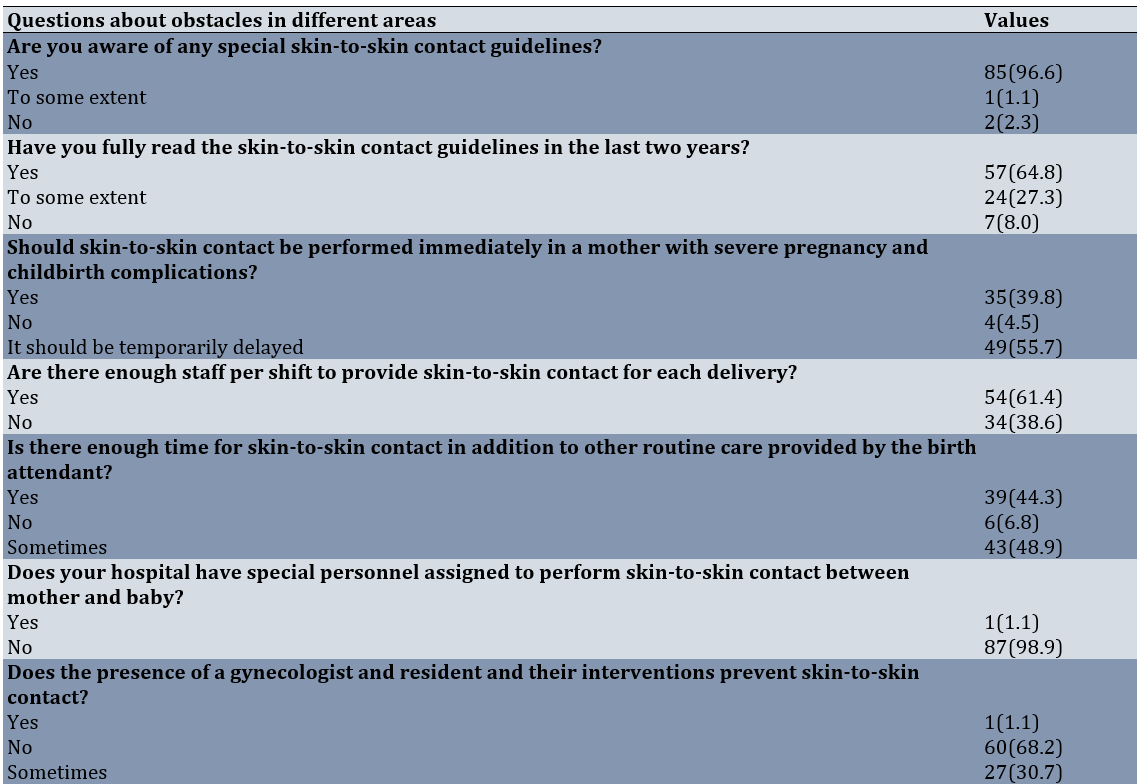

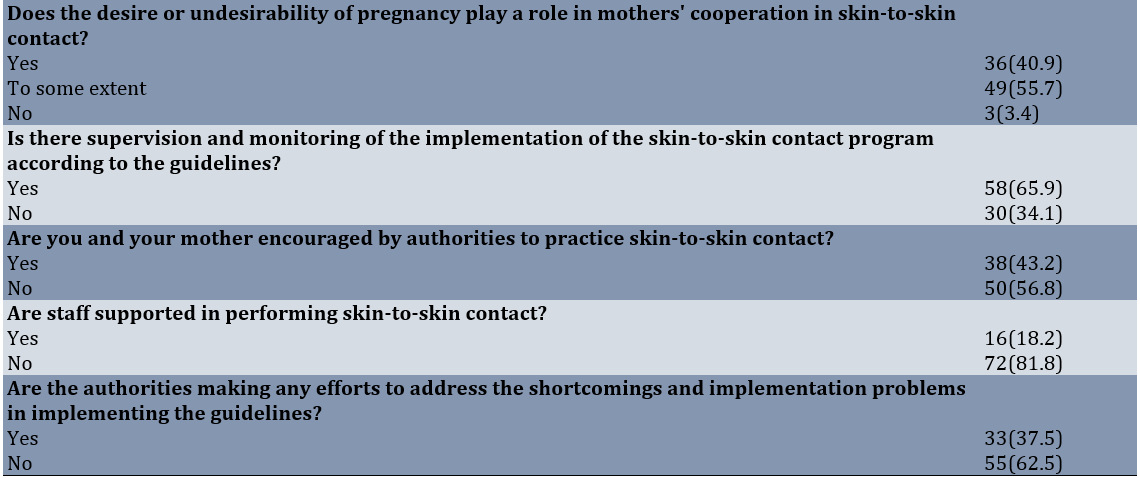

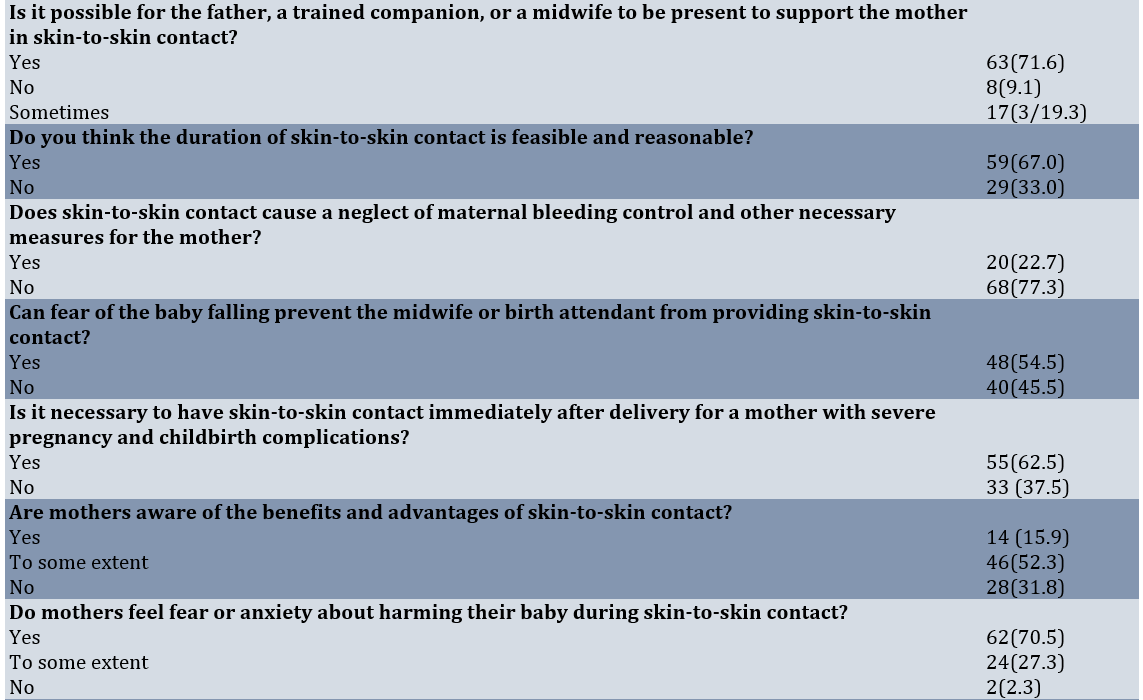

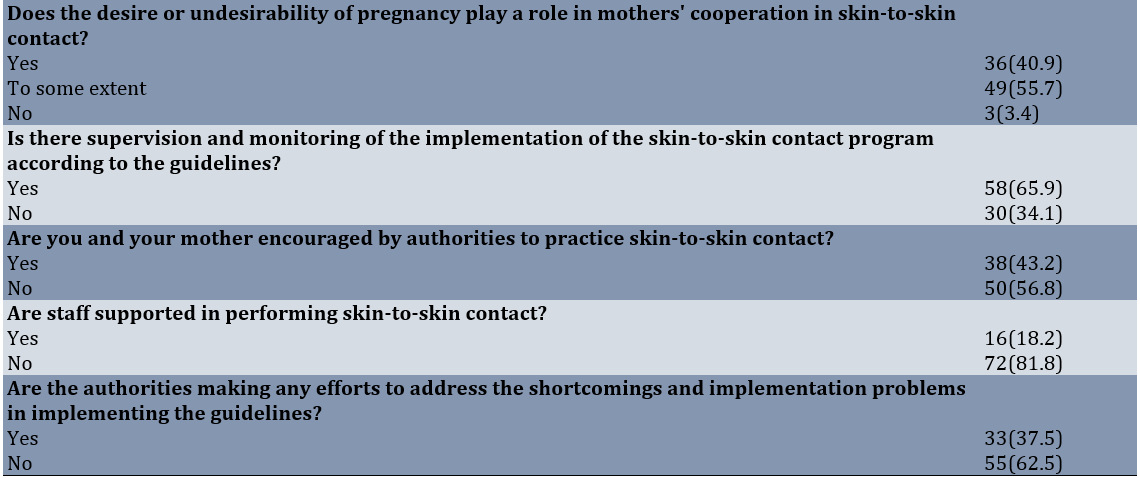

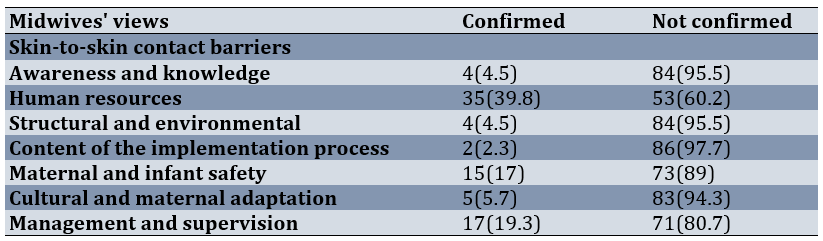

The most common obstacle confirmed by midwives was related to management and supervision, while the least common obstacle was related to the content of the implementation process (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency of views of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city regarding barriers to skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn at birth

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the barriers to implementing the guidelines for skin-to-skin contact between mothers and newborns at birth from the perspective of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj, Iran. Skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby immediately after birth is a standard, simple, inexpensive, and essential practice for the health of both mother and baby, and it is the fourth of ten measures promoted by baby-friendly hospitals to encourage breastfeeding [6]. However, in most Iranian hospitals, care is not provided according to these guidelines. This study is one of the first quantitative studies conducted in the country with the objective of identifying the barriers to implementing this care from the perspective of midwives working in Yasuj hospitals, who play a key role in ensuring the implementation of these guidelines. Regarding the demographic and occupational status of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city, most midwives were in the 25 to 34 age group, married, held a bachelor's degree, and had work experience in maternity wards of about one to five years, with less than five years of experience in other departments. Approximately half of them worked exclusively in maternity wards. In the study by Nahidi et al., the majority of midwives working in teaching and non-teaching hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences were also married (78%) and held the highest educational level (86%) [22]. Most midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city were currently working in the maternity ward, with a smaller percentage working in the postpartum ward and gynecological surgery ward. It is evident that midwives' views are influenced by their work in the maternity ward and their experience in this area, which is one of the strengths of this study. This finding is consistent with studies from other regions and countries aimed at identifying barriers to maternal-neonate skin-to-skin contact. These studies also surveyed medical staff, midwives, and personnel working in maternal and newborn care wards [22-24, 27, 29-33].

The frequency of working midwives in terms of barriers to awareness and knowledge in performing skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn at birth showed that most midwives were aware of the guidelines. For most questions, a significant number of midwives chose the correct answer; however, regarding issues such as reading the instructions and performing skin-to-skin contact in mothers with severe complications, the correct answers were not significantly frequent. A qualitative study by Alenchery et al. in Bangalore, India, found that all study participants, including consultants and residents/graduates from obstetrics, pediatrics, and nursing departments, were aware of and practiced skin-to-skin contact at birth, recognizing some of its benefits in the delivery room [23]. These findings were consistent with ours. However, contrary to our findings, a review by Fitriana in Indonesia identified two major barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact between mothers and infants, one of which was the lack of awareness and knowledge among healthcare personnel [34]. Similarly, Ebrahimi et al. conducted a qualitative study in Urmia and concluded that the barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact between mothers and infants included four dimensions, one of which was process barriers (knowledge, awareness, and skills of personnel) [26]. In Nahidi et al.'s study, 58.9% of working midwives in teaching hospitals and 57.4% in non-teaching hospitals reported being aware of skin-to-skin contact, and 44.6% in teaching hospitals and 33.3% in non-teaching hospitals performed it correctly [22].

Regarding the frequency of human resource barriers in implementing skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby, more than one-third of midwives did not consider the number of personnel per shift to be sufficient for performing skin-to-skin contact, and nearly half of them believed that there was not enough time for skin-to-skin contact in addition to the other routine care provided by the birth attendant. Almost all of them stated that there were no dedicated personnel for skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby, and nearly one-third considered the presence of specialists, residents, and medical interventions to sometimes be a barrier to skin-to-skin contact. A qualitative study by Balatero et al. found that providing immediate skin-to-skin contact during cesarean delivery is not a priority for all team members. Challenges related to safety, nursing staffing, logistics, and professional barriers were among the obstacles perceived by nurses. They considered the presence of adequate nursing staff in the operating room to be essential [31]. Abdulghani et al. reported that a lack of professional cooperation, staff, and time constraints, and an obstetric medical environment that prioritizes interventions over skin-to-skin contact were perceived barriers [32]. In a qualitative study by Alenchary et al. in Bangalore, India, the main barriers identified were staff shortages (nurses), time constraints, difficulty in deciding eligibility for skin-to-skin contact, safety concerns, interference with clinical routines, and interdepartmental issues [23]. Chan et al., in a systematic study, stated that in the health system, health workers and health facilities are two important factors in implementing skin-to-skin contact [30]. In our study, the frequency of midwives acknowledging human resource barriers was relatively high. Consistent with the present study, human resource barriers (lack of staff, personnel, etc.) have also been mentioned in the studies by Alenchary et al. in India [23], Balatero et al. [31], Abdulghani et al. in Saudi Arabia [32], Ebrahimi et al. [26], and Cho et al. in Gambia [27].

Regarding the frequency of structural and environmental barriers from the midwives' perspective, the environmental and structural conditions of the delivery room, including temperature, silence, light, equipment, etc., were considered appropriate by the majority of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj. Only the possibility of having a trained companion present to perform skin-to-skin contact was less frequently mentioned as a barrier in the midwives' perspective on structural and environmental barriers. Unlike our study, where structural and environmental barriers were not identified as significant obstacles from the perspective of midwives, Abdulghani et al. in Saudi Arabia found that the birth environment acted as a barrier, causing midwives to prioritize interventions over skin-to-skin contact [32]. Additionally, in a study by Ebrahimi et al., environmental factors were identified as barriers to skin-to-skin contact [26]. In a qualitative study from the perspective of health workers in Gambia [27], Cho et al. also reported the delivery environment, bed, space, and facilities as structural and environmental barriers. Therefore, based on the perspective of midwives, we do not face significant environmental and structural problems in hospitals in Yasuj city, except for the possibility of a trained companion being present with the mother, which is also considered an implementation and policy-making factor.

Regarding the frequency of content barriers to the process of implementing the guidelines, most midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj considered the timing of skin-to-skin contact, the steps involved, and the necessity of this care to be reasonable and feasible. Very few midwives confirmed the existence of content barriers to the process. Chan et al. identified time for skin-to-skin contact as a barrier to its implementation in a systematic study [30]. Alenchery et al. also recognize time constraints as a barrier in India, with most participants considering an hour as impractical and promoting skin-to-skin contact for 5-15 minutes [23]. In our study, about one-third of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj considered the one-hour duration (according to the procedure) to be impractical. Ebrahimi et al. also highlight the challenges of the procedure as a content barrier in their study [26]. However, in our study, the frequency of these barriers was insignificant, possibly because most of the midwives participating had sufficient knowledge and awareness, and only a small number of midwives identified structural and environmental problems as barriers. Therefore, the content of the guideline implementation process, which depends on these factors, was not perceived as a significant barrier from their perspective.

Regarding the frequency of barriers to maternal and infant safety from the midwives' perspective, more than half of the midwives considered fear of the baby falling to be a barrier to skin-to-skin contact. Nearly a quarter of them considered skin-to-skin contact to be a reason for neglecting maternal bleeding, and more than a third of the midwives considered this care unnecessary in cases of severe birth complications. However, a significant number of midwives considered the safety of delivery room facilities to be adequate. In line with the present study, a review by Chan et al. identified medical concerns about the health status of the mother or the newborn as one of the barriers to skin-to-skin contact from the perspective of health systems [30]. Compared to other barriers, safety-related concerns were also among the barriers approved by a relatively higher percentage of midwives. Our findings are consistent with those of Napoli in the United States [33], Chan et al. [30], Alenchery et al. in India [23], Balatero et al. [31], and Chou et al. in Gambia [27], all of whom identifiy safety concerns (such as maternal pain and fatigue, bed safety, etc.) as barriers to skin-to-skin contact. Additionally, Mukherjee et al. reported that postpartum pain and fatigue were barriers to skin-to-skin contact, with a frequency of 8% [25].

Regarding the frequency of cultural barriers and maternal adaptation in implementing skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby at birth from the perspective of midwives, half of the midwives reported that mothers were somewhat aware of the benefits of skin-to-skin contact, while nearly one-third of mothers lacked the necessary knowledge. A small percentage of midwives stated that mothers had sufficient knowledge. Almost all midwives believed that mothers were either completely or somewhat afraid of harming their babies during skin-to-skin contact. In the study by Napoli, 94% of nurses identified "lack of awareness among mothers" as the highest barrier [33]. Mukherjee et al., in a cross-sectional study, also found that 82.25% of mothers were unaware of the benefits of skin-to-skin contact, making it the most common barrier to its implementation [25]. According to Ekholuental et al. in Nigeria, there was a 65% reduction in skin-to-skin contact among women from low-media-using communities compared to those from high-media-using communities. They concluded that greater awareness needs to be created among Nigerian women to understand the importance of this care, especially for the health of newborns [28]. The level of mothers' lack of awareness, as observed from our midwives' perspectives in the areas of cultural barriers and maternal adaptation, aligns with these studies and is notably high. This highlights the need to incorporate a skin-to-skin contact education program for mothers and newborns in the prenatal care program. From the perspective of most midwives, maternal privacy during care was maintained, and the gender of the infant and birth order, unlike unintended pregnancies, were not considered barriers to skin-to-skin contact. In the study by Alenchery et al., gender bias regarding the infant and cultural practices are identified as secondary barriers, similar to our findings [23]. Only a few of our midwives acknowledged cultural barriers [29].

Regarding the frequency of managerial and supervisory barriers from the midwives' perspective, most midwives had completed in-service training courses on skin-to-skin care for both midwives and mothers and believed that the necessary training resources were available. Among the managerial issues, these two were considered appropriate from the midwives' perspective. However, during the process of providing this care, more than half of the midwives confirmed the lack of encouragement, nearly four-fifths confirmed the lack of support from staff, nearly two-thirds confirmed the lack of efforts to address deficiencies, and more than one-third confirmed the lack of supervision in implementing instructions by managers and officials.

In general, a relatively significant percentage of respondents acknowledged managerial and supervisory barriers to skin-to-skin contact (in-service training courses, supervision and monitoring, staff encouragement, etc.). Studies by Chan et al. [30], Alenchery et al. [23], Balatero et al. [31], Fitriana [34], and Ebrahimi et al. [26] identified managerial barriers, such as supervision, monitoring, logistics, and training, as obstacles to implementing skin-to-skin contact between mothers and infants—barriers that were also considered major in our study. Sjömar et al., in their examination of caregivers' experiences with maternal kangaroo care in Bangladesh, found that social support structures and positive attitudes toward the care method were supportive conditions for caregivers performing kangaroo care in Bangladesh [29]. Additionally, in a study by Chan et al., social support, empowerment, encouragement, and assistance in implementing kangaroo care were identified as policies that facilitate the implementation of skin-to-skin contact between mother and infant [30].

From the perspective of midwives in Yasuj, barriers related to midwives' awareness and knowledge, structural and environmental barriers, content barriers to the implementation of the guideline, and cultural barriers were secondary, as their overall frequency was insignificant. In contrast, human resource barriers, management and supervisory barriers, and maternal and newborn safety barriers were identified as the primary barriers to implementing the guideline for skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn, with higher overall frequency.

In this regard, suggestions can be made to officials and planners to remove the barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact in order to promote maternal and newborn health. These suggestions include: providing sufficient human resources and allocating special personnel for skin-to-skin contact to address human resource barriers; allowing trained companions to assist the delivery team in overcoming maternal and newborn safety barriers; holding regular in-service courses, encouraging personnel, offering more support to staff, and ensuring supervision and monitoring to address management and supervisory barriers; and including an education program for pregnant mothers about the benefits of skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn in prenatal care principles.

For ease of access, interviews were conducted with midwives during their shifts. Due to time constraints, there may not have been enough time to answer all questions accurately.

Investigating the barriers to implementing the skin-to-skin contact guidelines for mothers and newborns at birth from the perspectives of mothers, hospital managers, and officials, as well as examining the impact of full implementation and the duration of skin-to-skin contact on the mental and physical health of mothers and newborns, is also recommended for future research.

Conclusion

The main barriers to implementing the skin-to-skin contact guideline at birth are human resource, managerial and supervisory, and maternal and newborn safety barriers, respectively.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank the Student Research Committee of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, the Research Council of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, and all midwives who participated in this study, as well as those who helped us conduct the research.

Ethical considerations: All ethical principles, including obtaining informed consent and maintaining the confidentiality of participant information, were observed. This article is derived from a research project at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, with the ethical code IR.YUMS.REC.323/140.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: All authors of the article collaborated in various stages of the research and preparation of the article.

Authors' Contribution: Shabanikordsholi Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (35%); Safari M (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%); Parvizi S (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Shabanikordsholi P (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (5%)

Funding/Support: This research was conducted with the financial support of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

The first hour after birth is a unique period referred to as the “sensitive period,” during which the newborn exhibits elevated levels of catecholamines that keep it alert. Simultaneously, the maternal hormonal response, involving oxytocin and prolactin, fosters mother-infant bonding [1, 2]. Separating the infant from the mother during this time, even briefly, can adversely impact the infant's physical and mental health and survival [1, 3].

According to John Bowlby's attachment theory, mothers who are available to their children from the beginning and respond to their needs foster a sense of peace and security, encouraging the child to confidently explore their surroundings [4]. Adequate skin-to-skin contact within the first hour of life promotes this sense of security in the infant. Conversely, premature separation may disrupt the mother-infant bond, diminish emotional responsiveness between them, and negatively affect maternal behavior [5].

Skin-to-skin contact at birth is a recognized standard of care for healthy newborns. As a safe and cost-effective intervention, it reduces maternal and infant mortality, particularly in developing countries, yet its acceptance and implementation remain limited [6, 7]. When skin-to-skin contact is initiated immediately after birth, the infant is able to seek out the breast and begin breastfeeding—a natural instinctive behavior referred to as the "breast crawl" [8].

The infant typically exhibits this instinctive behavior within 30 to 60 minutes, although in some cases, breastfeeding may take up to an hour. Even in such instances, skin-to-skin contact remains highly beneficial and valuable [9]. Placing the naked infant on the mother's bare abdomen or chest immediately after birth helps prevent hypothermia and hypoglycemia, reduces the risk of neonatal sepsis, and stabilizes the infant's heart rate and breathing [10, 11]. It also improves heart and lung function, facilitates the transfer of beneficial bacteria, reduces infant crying, alleviates pain during medical procedures, strengthens the mother-infant bond, and aids the infant’s adaptation to the external environment [12].

One of the most critical benefits of skin-to-skin contact is preventing hypothermia in the newborn. However, in many hospitals, instead of prioritizing and promoting skin-to-skin contact as a means of preventing hypothermia, other measures are emphasized. These include the use of warmers, encouraging early breastfeeding, wrapping the baby in a warm towel, turning on room heaters, and delaying the baby’s first bath [13, 14].

For mothers, the benefits of skin-to-skin contact include a shorter third stage of labor with earlier placental separation and expulsion, reduced postpartum bleeding, and a decreased need for postpartum analgesia [15, 16]. Additionally, skin-to-skin contact lowers maternal anxiety by regulating cortisol production, enhances maternal bonding and caregiving behaviors, and reduces symptoms of postpartum depression [17].

According to the 2021 national guidelines, during skin-to-skin contact, the baby's health, breathing, and body temperature are monitored. Even if an episiotomy or perineal repair is performed, skin-to-skin contact is maintained throughout the procedure [18]. However, non-urgent care, such as vitamin K injections, footprinting, vaccinations, weighing, and other measurements or procedures, is postponed until after skin-to-skin contact has been completed [9].

The implementation and definition of skin-to-skin contact vary in both practice and research studies, leading to inconsistencies [19]. The duration of skin-to-skin contact differs worldwide. For example, a French study reported an average duration of approximately 90 minutes [20]. In contrast, a 2013 cross-sectional study in Iran found that 98% of midwives conducted skin-to-skin contact for a minimum of 2 minutes and a maximum of 4 minutes [9]. Another study from 2013 reported that the adherence rate to skin-to-skin contact guidelines was 53% [21].

Potential barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact include concerns about hypothermia in the baby, the need for immediate examination or weighing, maternal stitches, the baby’s need for bathing, crowded delivery rooms, insufficient staff to care for the mother and baby, the baby’s lack of alertness or fatigue, and the mother’s unwillingness to participate [9].

Other barriers include a shortage of personnel, time constraints, challenges in determining whether the mother and baby are eligible for skin-to-skin contact or maternal hugging, lack of adequate and continuous training, an inappropriate environment for conducting the contact process, and insufficient systematic supervision by department managers [22, 23]. Allen et al. identified additional barriers, including the baby's restlessness and fear of falling, mothers wearing inappropriate clothing that restricts access to the bare chest, and unnecessary interventions by birth attendants, such as weighing and washing the baby, as primary reasons for not implementing skin-to-skin contact within the first hour of birth [24].

Mukherjee et al. reported that the most common reason for not performing skin-to-skin contact is a lack of awareness about its importance in infant care [25]. A qualitative study by Ebrahimi et al., involving interviews with delivery room managers, specialists, and staff, highlighted that inadequate training, lack of motivation, and insufficient managerial support, such as effective supervision and rewards, are significant obstacles to implementing skin-to-skin contact in Iran [26].

Given the poor implementation of national guidelines for this care in many hospitals, including those targeted by our study, and the absence of a comprehensive study investigating the perspectives of midwives—who play a critical role in maternal and newborn care at birth—it is clear that further research is needed. This study aimed to identify and address the barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact guidelines between mothers and newborns at birth, from the perspective of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj, Iran.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in 2024 and involved 88 midwives working in two hospitals in Yasuj, including Shahid Beheshti and Imam Sajjad.

The inclusion criteria required midwives to be working in the maternity, postpartum, gynecological surgery, neonatal, or administrative wards of the hospitals. Participants were also required to have at least one year of experience working in the maternity ward or be faculty members responsible for training students in these wards. Sampling was conducted using total population sampling. One midwife was excluded from the study due to her unwillingness to participate.

The data collection tool consisted of a researcher-designed questionnaire with two parts. The first part focused on the demographic and occupational characteristics of the midwives (12 questions), while the second part included questions related to the implementation of skin-to-skin contact and its methods (two questions). Additionally, the second part included questions addressing seven areas of barriers to skin-to-skin contact from the midwives' perspective. These areas were: barriers related to midwives' awareness and knowledge (14 questions), structural and environmental barriers (six questions), human resource barriers (six questions), content barriers (five questions), barriers to maternal and newborn safety (five questions), cultural barriers and maternal adaptation (nine questions), and management and supervisory barriers (seven questions). These questions were developed based on the study's objectives. The validity of the questionnaire was assessed using the content validity index (CVI). To calculate the CVI, seven faculty members, and professors from the midwifery department evaluated the relevance of each item in the seven areas on a four-point scale: not relevant (one), needs major revision (two), relevant but needs revision (three), and completely relevant (four). The number of evaluators who selected options three and four for each item was divided by the total number of evaluators. Items with a CVI score of less than 0.7 were deleted, scores between 0.7 and 0.79 were revised, and scores greater than 0.79 were considered acceptable. As a result, one question with a score below 0.7 was removed.

To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, the test-retest method was employed. The questionnaire was completed by seven midwives and then re-administered one week later. The correlation coefficient of the scores obtained from the two instances was calculated, yielding a value of 0.95, indicating high reliability.

After receiving approval from the Student Research Committee of the university and the Research Council (ethics code: IR.YUMS.REC.1403.032) and obtaining permission from the officials of Imam Sajjad and Shohada Gomnam hospitals, we visited the respective hospitals. After explaining the objectives of the project to the midwives and obtaining their informed consent, we conducted interviews with each midwife to complete the relevant questionnaires.

After the questionnaires were completed by the participating midwives, a score ranging from zero to two was assigned to determine the midwives' overall view of the barriers in the seven areas of the questionnaire. Each question was scored based on the number of response options (e.g., yes, no, to some extent). For the knowledge and awareness dimension, questions that measured knowledge and awareness were assigned a score of two for the correct option and zero for the incorrect option. For the other dimensions, the negative form of the questions was used in the scoring. The option that confirmed the obstacle received a score of two, the intermediate option received a score of one, and the option that did not confirm the obstacle received a score of zero.

Thus, a maximum of 30 points was assigned to the knowledge and awareness dimension, a maximum of 12 points each for the human resource and environmental/structural barriers dimensions, a maximum of 10 points each for the content barriers and barriers to maternal and newborn safety dimensions, a maximum of 18 points for the cultural barriers and maternal adaptation dimension, and a maximum of 14 points for the management and supervision dimension. A total of 104 points were possible across all dimensions. A score of 50% or more of the total score in each domain was considered confirmation of the midwives' view of the barrier, while a score below 50% was considered non-confirmation.

Data analysis was carried out using descriptive statistical indices, including absolute and relative frequency tables, measures of central tendency, and measures of dispersion (mean, standard deviation, etc.), utilizing SPSS version 16 software.

Findings

A total of 88 midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj participated in this study. Of these, 69 (78.4%) were employed at Imam Sajjad Hospital and 19 (21.6%) were employed at Shohada Gomnam Hospital. The minimum age was 25 years, and the maximum age was 59 years, with a mean age of 48.2 ± 35.91. The minimum length of work experience in the maternity ward was one year, and the maximum was 26 years, with a mean of 6.7 ± 6.86 years. The minimum length of work experience in other departments was zero, and the maximum was 24 years, with a mean of 4.2 ± 2.34 years. From the perspective of all midwives, skin-to-skin contact was routinely performed in their hospital; however, only 40 (45.5%) believed that this care was performed according to the guidelines, while 48 (54.5%) believed that skin-to-skin contact was not performed according to the guidelines in their hospital (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic and occupational characteristics of midwives working in Yasuj hospitals

The highest frequency of midwives participating in the study was in the age group of 25 to 34 years, and the lowest frequency was in the age group of 45 years and above. The highest frequency was observed in married individuals, and in terms of education, the highest frequency was for those holding a bachelor's degree. The highest frequency of work experience was in the one to five years range, while the lowest frequency was in the 16 to 20 years range. Most of the midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city were currently working in the maternity ward, and the lowest frequency of their workplace was in the gynecological surgery ward. The highest frequency of midwives working in the maternity ward was observed at Imam Sajjad Hospital.

Questions 1-3 relate to knowledge barriers, 4-7 to human resource barriers, 8 to structural and environmental barriers, 9 to content barriers in the implementation process, 10-12 to maternal and newborn safety barriers, 13-15 to cultural barriers and maternal adaptation, and 16-19 to management and supervision barriers. The most common obstacles were related to management and supervision and human resources, while the least common obstacles were related to structural, environmental, and content barriers in the implementation process (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of views of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city regarding the most common obstacles in different areas of implementing skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn at birth

The most common obstacle confirmed by midwives was related to management and supervision, while the least common obstacle was related to the content of the implementation process (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency of views of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city regarding barriers to skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn at birth

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the barriers to implementing the guidelines for skin-to-skin contact between mothers and newborns at birth from the perspective of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj, Iran. Skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby immediately after birth is a standard, simple, inexpensive, and essential practice for the health of both mother and baby, and it is the fourth of ten measures promoted by baby-friendly hospitals to encourage breastfeeding [6]. However, in most Iranian hospitals, care is not provided according to these guidelines. This study is one of the first quantitative studies conducted in the country with the objective of identifying the barriers to implementing this care from the perspective of midwives working in Yasuj hospitals, who play a key role in ensuring the implementation of these guidelines. Regarding the demographic and occupational status of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city, most midwives were in the 25 to 34 age group, married, held a bachelor's degree, and had work experience in maternity wards of about one to five years, with less than five years of experience in other departments. Approximately half of them worked exclusively in maternity wards. In the study by Nahidi et al., the majority of midwives working in teaching and non-teaching hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences were also married (78%) and held the highest educational level (86%) [22]. Most midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj city were currently working in the maternity ward, with a smaller percentage working in the postpartum ward and gynecological surgery ward. It is evident that midwives' views are influenced by their work in the maternity ward and their experience in this area, which is one of the strengths of this study. This finding is consistent with studies from other regions and countries aimed at identifying barriers to maternal-neonate skin-to-skin contact. These studies also surveyed medical staff, midwives, and personnel working in maternal and newborn care wards [22-24, 27, 29-33].

The frequency of working midwives in terms of barriers to awareness and knowledge in performing skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn at birth showed that most midwives were aware of the guidelines. For most questions, a significant number of midwives chose the correct answer; however, regarding issues such as reading the instructions and performing skin-to-skin contact in mothers with severe complications, the correct answers were not significantly frequent. A qualitative study by Alenchery et al. in Bangalore, India, found that all study participants, including consultants and residents/graduates from obstetrics, pediatrics, and nursing departments, were aware of and practiced skin-to-skin contact at birth, recognizing some of its benefits in the delivery room [23]. These findings were consistent with ours. However, contrary to our findings, a review by Fitriana in Indonesia identified two major barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact between mothers and infants, one of which was the lack of awareness and knowledge among healthcare personnel [34]. Similarly, Ebrahimi et al. conducted a qualitative study in Urmia and concluded that the barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact between mothers and infants included four dimensions, one of which was process barriers (knowledge, awareness, and skills of personnel) [26]. In Nahidi et al.'s study, 58.9% of working midwives in teaching hospitals and 57.4% in non-teaching hospitals reported being aware of skin-to-skin contact, and 44.6% in teaching hospitals and 33.3% in non-teaching hospitals performed it correctly [22].

Regarding the frequency of human resource barriers in implementing skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby, more than one-third of midwives did not consider the number of personnel per shift to be sufficient for performing skin-to-skin contact, and nearly half of them believed that there was not enough time for skin-to-skin contact in addition to the other routine care provided by the birth attendant. Almost all of them stated that there were no dedicated personnel for skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby, and nearly one-third considered the presence of specialists, residents, and medical interventions to sometimes be a barrier to skin-to-skin contact. A qualitative study by Balatero et al. found that providing immediate skin-to-skin contact during cesarean delivery is not a priority for all team members. Challenges related to safety, nursing staffing, logistics, and professional barriers were among the obstacles perceived by nurses. They considered the presence of adequate nursing staff in the operating room to be essential [31]. Abdulghani et al. reported that a lack of professional cooperation, staff, and time constraints, and an obstetric medical environment that prioritizes interventions over skin-to-skin contact were perceived barriers [32]. In a qualitative study by Alenchary et al. in Bangalore, India, the main barriers identified were staff shortages (nurses), time constraints, difficulty in deciding eligibility for skin-to-skin contact, safety concerns, interference with clinical routines, and interdepartmental issues [23]. Chan et al., in a systematic study, stated that in the health system, health workers and health facilities are two important factors in implementing skin-to-skin contact [30]. In our study, the frequency of midwives acknowledging human resource barriers was relatively high. Consistent with the present study, human resource barriers (lack of staff, personnel, etc.) have also been mentioned in the studies by Alenchary et al. in India [23], Balatero et al. [31], Abdulghani et al. in Saudi Arabia [32], Ebrahimi et al. [26], and Cho et al. in Gambia [27].

Regarding the frequency of structural and environmental barriers from the midwives' perspective, the environmental and structural conditions of the delivery room, including temperature, silence, light, equipment, etc., were considered appropriate by the majority of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj. Only the possibility of having a trained companion present to perform skin-to-skin contact was less frequently mentioned as a barrier in the midwives' perspective on structural and environmental barriers. Unlike our study, where structural and environmental barriers were not identified as significant obstacles from the perspective of midwives, Abdulghani et al. in Saudi Arabia found that the birth environment acted as a barrier, causing midwives to prioritize interventions over skin-to-skin contact [32]. Additionally, in a study by Ebrahimi et al., environmental factors were identified as barriers to skin-to-skin contact [26]. In a qualitative study from the perspective of health workers in Gambia [27], Cho et al. also reported the delivery environment, bed, space, and facilities as structural and environmental barriers. Therefore, based on the perspective of midwives, we do not face significant environmental and structural problems in hospitals in Yasuj city, except for the possibility of a trained companion being present with the mother, which is also considered an implementation and policy-making factor.

Regarding the frequency of content barriers to the process of implementing the guidelines, most midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj considered the timing of skin-to-skin contact, the steps involved, and the necessity of this care to be reasonable and feasible. Very few midwives confirmed the existence of content barriers to the process. Chan et al. identified time for skin-to-skin contact as a barrier to its implementation in a systematic study [30]. Alenchery et al. also recognize time constraints as a barrier in India, with most participants considering an hour as impractical and promoting skin-to-skin contact for 5-15 minutes [23]. In our study, about one-third of midwives working in hospitals in Yasuj considered the one-hour duration (according to the procedure) to be impractical. Ebrahimi et al. also highlight the challenges of the procedure as a content barrier in their study [26]. However, in our study, the frequency of these barriers was insignificant, possibly because most of the midwives participating had sufficient knowledge and awareness, and only a small number of midwives identified structural and environmental problems as barriers. Therefore, the content of the guideline implementation process, which depends on these factors, was not perceived as a significant barrier from their perspective.

Regarding the frequency of barriers to maternal and infant safety from the midwives' perspective, more than half of the midwives considered fear of the baby falling to be a barrier to skin-to-skin contact. Nearly a quarter of them considered skin-to-skin contact to be a reason for neglecting maternal bleeding, and more than a third of the midwives considered this care unnecessary in cases of severe birth complications. However, a significant number of midwives considered the safety of delivery room facilities to be adequate. In line with the present study, a review by Chan et al. identified medical concerns about the health status of the mother or the newborn as one of the barriers to skin-to-skin contact from the perspective of health systems [30]. Compared to other barriers, safety-related concerns were also among the barriers approved by a relatively higher percentage of midwives. Our findings are consistent with those of Napoli in the United States [33], Chan et al. [30], Alenchery et al. in India [23], Balatero et al. [31], and Chou et al. in Gambia [27], all of whom identifiy safety concerns (such as maternal pain and fatigue, bed safety, etc.) as barriers to skin-to-skin contact. Additionally, Mukherjee et al. reported that postpartum pain and fatigue were barriers to skin-to-skin contact, with a frequency of 8% [25].

Regarding the frequency of cultural barriers and maternal adaptation in implementing skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby at birth from the perspective of midwives, half of the midwives reported that mothers were somewhat aware of the benefits of skin-to-skin contact, while nearly one-third of mothers lacked the necessary knowledge. A small percentage of midwives stated that mothers had sufficient knowledge. Almost all midwives believed that mothers were either completely or somewhat afraid of harming their babies during skin-to-skin contact. In the study by Napoli, 94% of nurses identified "lack of awareness among mothers" as the highest barrier [33]. Mukherjee et al., in a cross-sectional study, also found that 82.25% of mothers were unaware of the benefits of skin-to-skin contact, making it the most common barrier to its implementation [25]. According to Ekholuental et al. in Nigeria, there was a 65% reduction in skin-to-skin contact among women from low-media-using communities compared to those from high-media-using communities. They concluded that greater awareness needs to be created among Nigerian women to understand the importance of this care, especially for the health of newborns [28]. The level of mothers' lack of awareness, as observed from our midwives' perspectives in the areas of cultural barriers and maternal adaptation, aligns with these studies and is notably high. This highlights the need to incorporate a skin-to-skin contact education program for mothers and newborns in the prenatal care program. From the perspective of most midwives, maternal privacy during care was maintained, and the gender of the infant and birth order, unlike unintended pregnancies, were not considered barriers to skin-to-skin contact. In the study by Alenchery et al., gender bias regarding the infant and cultural practices are identified as secondary barriers, similar to our findings [23]. Only a few of our midwives acknowledged cultural barriers [29].

Regarding the frequency of managerial and supervisory barriers from the midwives' perspective, most midwives had completed in-service training courses on skin-to-skin care for both midwives and mothers and believed that the necessary training resources were available. Among the managerial issues, these two were considered appropriate from the midwives' perspective. However, during the process of providing this care, more than half of the midwives confirmed the lack of encouragement, nearly four-fifths confirmed the lack of support from staff, nearly two-thirds confirmed the lack of efforts to address deficiencies, and more than one-third confirmed the lack of supervision in implementing instructions by managers and officials.

In general, a relatively significant percentage of respondents acknowledged managerial and supervisory barriers to skin-to-skin contact (in-service training courses, supervision and monitoring, staff encouragement, etc.). Studies by Chan et al. [30], Alenchery et al. [23], Balatero et al. [31], Fitriana [34], and Ebrahimi et al. [26] identified managerial barriers, such as supervision, monitoring, logistics, and training, as obstacles to implementing skin-to-skin contact between mothers and infants—barriers that were also considered major in our study. Sjömar et al., in their examination of caregivers' experiences with maternal kangaroo care in Bangladesh, found that social support structures and positive attitudes toward the care method were supportive conditions for caregivers performing kangaroo care in Bangladesh [29]. Additionally, in a study by Chan et al., social support, empowerment, encouragement, and assistance in implementing kangaroo care were identified as policies that facilitate the implementation of skin-to-skin contact between mother and infant [30].

From the perspective of midwives in Yasuj, barriers related to midwives' awareness and knowledge, structural and environmental barriers, content barriers to the implementation of the guideline, and cultural barriers were secondary, as their overall frequency was insignificant. In contrast, human resource barriers, management and supervisory barriers, and maternal and newborn safety barriers were identified as the primary barriers to implementing the guideline for skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn, with higher overall frequency.

In this regard, suggestions can be made to officials and planners to remove the barriers to implementing skin-to-skin contact in order to promote maternal and newborn health. These suggestions include: providing sufficient human resources and allocating special personnel for skin-to-skin contact to address human resource barriers; allowing trained companions to assist the delivery team in overcoming maternal and newborn safety barriers; holding regular in-service courses, encouraging personnel, offering more support to staff, and ensuring supervision and monitoring to address management and supervisory barriers; and including an education program for pregnant mothers about the benefits of skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn in prenatal care principles.

For ease of access, interviews were conducted with midwives during their shifts. Due to time constraints, there may not have been enough time to answer all questions accurately.

Investigating the barriers to implementing the skin-to-skin contact guidelines for mothers and newborns at birth from the perspectives of mothers, hospital managers, and officials, as well as examining the impact of full implementation and the duration of skin-to-skin contact on the mental and physical health of mothers and newborns, is also recommended for future research.

Conclusion

The main barriers to implementing the skin-to-skin contact guideline at birth are human resource, managerial and supervisory, and maternal and newborn safety barriers, respectively.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank the Student Research Committee of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, the Research Council of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, and all midwives who participated in this study, as well as those who helped us conduct the research.

Ethical considerations: All ethical principles, including obtaining informed consent and maintaining the confidentiality of participant information, were observed. This article is derived from a research project at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, with the ethical code IR.YUMS.REC.323/140.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: All authors of the article collaborated in various stages of the research and preparation of the article.

Authors' Contribution: Shabanikordsholi Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (35%); Safari M (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%); Parvizi S (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Shabanikordsholi P (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (5%)

Funding/Support: This research was conducted with the financial support of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

References

1. Widström AM, Brimdyr K, Svensson K, Cadwell K, Nissen E. Skin-to-skin contact the first hour after birth, underlying implications and clinical practice. Acta Paediatr. 2019;108(7):1192-204. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/apa.14754]

2. Safari K, Saeed AA, Hasan SS, Moghaddam-Banaem L. The effect of mother and newborn early skin-to-skin contact on initiation of breastfeeding, newborn temperature and duration of third stage of labor. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13(1):32. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13006-018-0174-9]

3. Moore JW. Moore's federal practice. 10th ed. Newtonville: Matthew Bender & Company; 2016. [Link]

4. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Fredrickson BL, Wagenaar WA, Loftus G. Atkinson & Hilgard's introduction to psychology. 15th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2009. [Link]

5. Girish M, Subramaniam G. The golden minute after birth-beyond resuscitation. Int J Adv Med Health Res. 2019;6(2):41-5. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/IJAMR.IJAMR_89_19]

6. Brimdyr K, Cadwell K, Stevens J, Takahashi Y. An implementation algorithm to improve skin‐to‐skin practice in the first hour after birth. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(2):e12571. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/mcn.12571]

7. Conde-Agudelo A, Belizán JM, Diaz-Rossello J. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;16:(3):CD002771. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002771.pub2]

8. Heydarzadeh M, Goodarzi F, Jafari Pardasty H. Breast crawl. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2010. [Persian] [Link]

9. Afrakhte M, Afshariani R, Ehdaeivand F, Barakati H, Ravari M, Sadvandian S, et al. Training guide for healthcare workers, implementation of skin-to-skin contact. Qom: ANDISHE MANDEGAR; 2021. [Persian] [Link]

10. Guala A, Boscardini L, Visentin R, Angellotti P, Grugni L, Barbaglia M, et al. Skin-to-skin contact in cesarean birth and duration of breastfeeding: A cohort study. Sci World J. 2017;2017:1940756. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2017/1940756]

11. Boundy EO, Dastjerdi R, Spiegelman D, Fawzi WW, Missmer SA, Lieberman E, et al. Kangaroo mother care and neonatal outcomes: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):e20152238. [Link] [DOI:10.1542/peds.2015-2238]

12. Farouk Abolwafa N, Boshra Shehata H, Mohammed Ali H. Effect of skin-to-skin contact between mothers and newborns at birth on temperature, oxygen saturation, and initiation of breast feeding. Egypt J Health Care. 2022;13(2):1831-42. [Link] [DOI:10.21608/ejhc.2022.264766]

13. Varma DS, Khan ME, Hazra A. Increasing postnatal care of Mothers and newborns including follow-up cord care and thermal care in rural Uttar Pradesh. J Fam Welf. 2010;56:31. [Link]

14. Sarin J, Jeeva S, Geetanjli PS. Practices of auxiliary nurse midwives regarding care of baby at birth. Nurs Midwifery Res J. 2011;7(3):110. [Link] [DOI:10.33698/NRF0124]

15. Marín Gabriel MA, Llana Martín I, López Escobar A, Fernández Villalba E, Romero Blanco I, Touza Pol P. Randomized controlled trial of early skin-to-skin contact: Effects on the mother and her newborn. Acta Pediatr. 2010;99(11):1630-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01597.x]

16. Wagner DL, Lawrence S, Xu J, Melsom J. Retrospective chart review of skin-to-skin contact in the operating room and administration of analgesic and anxiolytic medication to women after cesarean birth. Nurs Womens Health. 2018;22(2):116-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nwh.2018.02.005]

17. Cooijmans KHM, Beijers R, Rovers AC, De Weerth C. Effectiveness of skin-to-skin contact versus care-as-usual in mothers and their full-term infants: Study protocol for a parallel-group randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):154. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12887-017-0906-9]

18. National guidelines "establishing skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby immediately after birth and initiating breastfeeding within the first hour of birth". Tehran: Department of Children's Health and Promotion of Breastfeeding; Neonatal Health Department; Department of Maternal Health; Population, Family and School Health Office; Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education; 2021. [Persian] [Link]

19. Brimdyr K, Stevens J, Svensson K, Blair A, Turner-Maffei C, Grady J, et al. Skin-to-skin contact after birth: Developing a research and practice guideline. Acta Paediatr. 2023;112(8):1633-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/apa.16842]

20. Robiquet P, Zamiara PE, Rakza T, Deruelle P, Mestdagh B, Blondel G, et al. Observation of skin-to-skin contact and analysis of factors linked to failure to breastfeed within 2 hours after birth. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11(3):126-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/bfm.2015.0160]

21. Jafari N, Maleki A, Zinali A, Bayat R, Ghaffari A, Gholami H. Examining the frequency of skin-to-skin contact and the initiation of breastfeeding in the first hour of birth in full-term infants born in Ayatollah Mousavi Hospital, Zanjan, 2023. Sci J Nurs Midwifery Paramed Fac. 2024;9(4):366-82. [Persian] [Link]

22. Nahidi F, Tavafian SS, Haidarzade M, Hajizadeh E. A survey on midwives' opinions about skin to skin contact between mother and newborn, immediately After birth. J Med Counc Iran. 2013;31(2):124-32. [Persian] [Link]

23. Alenchery AJ, Thoppil J, Britto CD, De Onis JV, Fernandez L, Suman Rao PN. Barriers and enablers to skin-to-skin contact at birth in healthy neonates-a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):48. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12887-018-1033-y]

24. Allen J, Parratt JA, Rolfe MI, Hastie CR, Saxton A, Fahy KM. Immediate, uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding after birth: A cross-sectional electronic survey. Midwifery. 2019;79:102535. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2019.102535]

25. Mukherjee D, Chandra Shaw S, Venkatnarayan K, Dudeja P. Skin-to-skin contact at birth for vaginally delivered neonates in a tertiary care hospital: A cross-sectional study. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76(2):180-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.mjafi.2018.11.008]

26. Ebrahimi M, Jahanfar S, Takian A, Khakbazan Z, Vazifekhah S, vatandoust D, et al. Barriers of skin-to-skin contact in the first hour of life in healthy term infants: A qualitative study. Nurs Midwifery J. 2022;20(3):178-200. [Persian] [Link]

27. Cho YC, Gai A, Diallo BA, Samateh AL, Lawn JE, Martinez-Alvarez M, et al. Barriers and enablers to kangaroo mother care prior to stability from perspectives of Gambian health workers: A qualitative study. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:966904. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fped.2022.966904]

28. Ekholuenetale M, Barrow A, Benebo FO, Idebolo AF. Coverage and factors associated with mother and newborn skin-to-skin contact in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):603. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-021-04079-8]

29. Sjömar J, Ottesen H, Banik G, Rahman AE, Thernström Blomqvist Y, Rahman SM, et al. Exploring caregivers' experiences of Kangaroo Mother Care in Bangladesh: A descriptive qualitative study. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280254. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0280254]

30. Chan G, Bergelson I, Smith ER, Skotnes T, Wall S. Barriers and enablers of kangaroo mother care implementation from a health systems perspective: A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(10):1466-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapol/czx098]

31. Balatero JS, Spilker AF, McNiesh SG. Barriers to skin-to-skin contact after cesarean birth. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2019;44(3):137-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NMC.0000000000000521]

32. Abdulghani N, Edvardsson K, Amir LH. Health care providers' perception of facilitators and barriers for the practice of skin-to-skin contact in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study. Midwifery. 2020;81:102577. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2019.102577]

33. Napoli RA. Perceived barriers to skin to skin care from maternal and nurse perspectives [dissertation]. Los Angeles: California State University; 2015. [Link]

34. Fitriana F. Barriers and facilitators in implementing skin-to-skin contact after birth: A systematic review. Syntax Fusion J Nas Indones. 2021;1(9). [Link]