Volume 6, Issue 1 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(1): 3-9 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/12/12 | Accepted: 2025/01/19 | Published: 2025/01/29

Received: 2024/12/12 | Accepted: 2025/01/19 | Published: 2025/01/29

How to cite this article

Sadat Hosseini A, Alviri S, Pakzad P, Rostamian F, Rajabi M. Relationship between Burnout and Childbearing Attitudes Among Female Pediatric Nurses. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (1) :3-9

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-300-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-300-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Pediatric Nursing and Neonatal Intensive Care, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Student Research Committee, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

2- Student Research Committee, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (1056 Views)

Introduction

A young population is a critical driver of a nation’s economic growth and societal development. As the primary contributors to the labor force, young individuals bring innovation and energy to various sectors, thereby fostering economic advancement and technological progress [1, 2]. In contrast, an aging population presents significant challenges, including increased healthcare costs, strained pension systems, and reduced workforce availability, which can slow economic growth and innovation [3, 4].

In recent decades, fertility rates have declined worldwide, becoming a critical concern for governments, policymakers, and researchers [5]. Many countries, including Iran, are witnessing below-replacement fertility rates, which puts them at risk of an aging population. This demographic shift poses a serious hindrance to the country’s development [6]. A recent study revealed that the total fertility rate (TFR) in Tehran, Iran, has experienced a notable decline. The results indicated a steep downward trend over the next decade, with the TFR decreasing from 1.4 children per woman in 2019 to an estimated 1.06 children per woman by 2029 [7]. Social, cultural, and economic changes have altered the way people view marriage, parenthood, and family life [8, 9]. Shifts in gender roles, financial instability, delayed marriages, and the pursuit of higher education and careers (particularly among women) have contributed to reduced fertility rates [10-12]. In Iran, where the fertility rate has dropped dramatically over the past few decades, concerns about the population’s long-term sustainability have become a national priority [13].

Healthcare professionals, especially nurses, constitute a substantial part of the working population in every society, making their attitudes toward fertility a critical factor in shaping population dynamics [14, 15]. Nurses face unique challenges in balancing personal and professional life, which can significantly influence their family decisions [16]. In pediatric nursing, the situation is even more complex. These nurses spend much of their time caring for children and interacting with families, which profoundly shapes their perspectives on parenthood [17, 18]. On the one hand, close exposure to children may naturally inspire a strong desire for parenthood among pediatric nurses. On the other hand, the emotional and physical demands of their profession can lead to burnout, which may negatively affect their attitudes toward childbearing.

Burnout, a psychological condition resulting from prolonged occupational stress, is a prevalent issue among healthcare workers, particularly those in high-pressure environments like pediatric units [19-21]. A systematic review revealed that the prevalence of burnout syndrome among pediatric intensive care unit nurses ranges from 42% to 77% [22]. Also, 38.6% of pediatric Spanish nurses have high levels of burnout [23]. Pediatric nurses encounter burnout due to the emotional and physical demands of their role. Caring for critically ill children, supporting distressed families, and witnessing suffering or loss can lead to emotional exhaustion and ultimately burnout [24-26]. Long hours, high workloads, and staffing shortages further exacerbate the issue, making pediatric nurses particularly vulnerable to burnout [27, 28].

Studies have revealed that burnout can significantly affect the professional performance and attitudes of nurses. There is a significant inverse relationship between missed nursing care and job burnout in nurses in Iran, suggesting that higher levels of burnout are associated with an increased likelihood of missed nursing care [29]. According to a systematic review, burnout may negatively impact pediatric nurses’ attitudes toward patient safety in acute hospital settings [21]. Another study conducted in Iraq reported that higher levels of burnout are significantly associated with an increased intention to leave the nursing profession [30]. Given the significant impact of burnout on nurses’ professional decisions, it is reasonable to posit that burnout may also influence personal life decisions, including family-related choices such as childbearing.

Burnout can reduce the emotional and mental resources necessary for envisioning and managing parenthood. For many nurses, the thought of taking on additional caregiving responsibilities at home can seem overwhelming [31-33]. Consequently, they may develop negative or ambivalent attitudes toward childbearing, leading to delays in starting a family or choosing not to have children at all. Nurses experiencing burnout might view parenthood as an additional source of stress rather than a fulfilling life goal [32, 34].

The relationship between burnout and childbearing attitudes is an underexplored area of research, particularly among pediatric nurses. Developing strategies to support nurses’ family decisions is essential, not only for improving their quality of life but also for addressing broader concerns about population trends and fertility rates in Iran and beyond. Given the high levels of burnout in nurses’ work and the declining fertility trends globally and in Iran, it is crucial to understand how occupational burnout influences reproductive intentions. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between burnout and attitudes toward childbearing among female pediatric nurses.

Instrument and Methods

Study design, Subjects, and setting

This correlational study assessed female nurses employed at selected pediatric hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, including the Children’s Medical Center and Bahrami Hospitals, in 2024. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria included voluntary participation, being a married female nurse with at least a bachelor’s degree, and having a minimum of six months of clinical experience. Nurses who did not answer more than 10% of the questions were excluded from the study.

Sample size

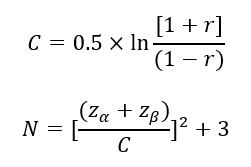

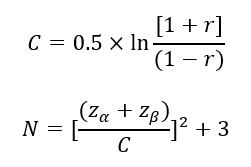

To calculate the sample size, a 95% confidence level and 80% statistical power were applied, with an assumed minimum correlation coefficient of 0.20 between the variables. The minimum required sample size was determined to be 194 participants using the following equation:

Research tools

Data were collected using a demographic information form, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, and the Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing Scale. The questionnaires were distributed to participants in person during their shifts. To ensure a high response rate and accurate data collection, the research team was available to address any questions or concerns during the completion of the questionnaire.

Demographic information form: This form collected information, such as age, number of children, average number of shifts per month, and level of education.

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: This tool was developed by Kristensen et al. in 2005 and consists of 19 items across three dimensions, including personal burnout (six items, total score ranging from 0 to 30), work-related burnout (seven items, total score ranging from 0 to 35), and client-related burnout (six items, total score ranging from 0 to 30). Each dimension is evaluated separately, with no overall score calculated. Responses are provided on a five-point Likert scale, where zero indicates “never” or “very low degree,” and five represents “always” or "very high degree” [35].

Mahmoudi et al. validated the Persian version of the inventory, maintaining the 19-item structure but dividing it into four dimensions, namely personal burnout (seven items, total score ranging from zero to 35), nature of work-related burnout (three items, total score ranging from zero to 15), work-aversion-related burnout (three items, total score ranging from zero to 15), and client-related burnout (six items, total score ranging from zero to 30). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the dimensions ranged between 0.84 and 0.89, confirming the reliability of the tool [36]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the dimensions of personal burnout, nature of work-related burnout, work-aversion-related burnout, and client-related burnout were 0.86, 0.83, 0.86, and 0.87, respectively, confirming the reliability of this tool.

Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing Scale: This scale was originally developed by Söderberg et al. in 2013. It comprises 27 items across three dimensions, namely the significance of fertility for the future (nine items, total score ranging from nine to 45), childbearing as a present barrier (12 items, total score ranging from 12 to 60), and childbearing as part of social identity (six items, total score ranging from six to 30). Each dimension is scored independently, without generating an overall score. Responses are rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating stronger agreement with the respective dimension [37]. Kordzanganeh and Mohammadian validated the Persian version of this scale, which includes 20 items divided into four dimensions, including postponing childbearing to a future time (five items, total score ranging from five to 25), childbearing as a hindrance (five items, total score ranging from five to 25), fertility as a future goal (six items, total score ranging from six to 30), and childbearing as social identity (four items, total score ranging from four to 20). They also reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 for the Persian version, confirming its reliability [38]. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the dimensions of postponing childbearing to a future time, childbearing as a hindrance, fertility as a future goal, and childbearing as a social identity were 0.85, 0.87, 0.84, and 0.86, respectively, confirming the reliability of the tool.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software 16. Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation, were used alongside inferential statistics, including Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed the normal distribution of the data. A significance level of p<0.05 was set to determine statistical significance.

Findings

Demographic characteristics

A total of 194 female pediatric nurses participated in the study. The participants had an average age of 33.26±7.00 years, and most held a bachelor’s degree (86.1%), while 13.9% held a master’s degree or higher. On average, the nurses had one child (1.00±0.56) and worked 26.99±1.83 shifts per month.

Descriptive statistics of burnout and childbearing attitudes

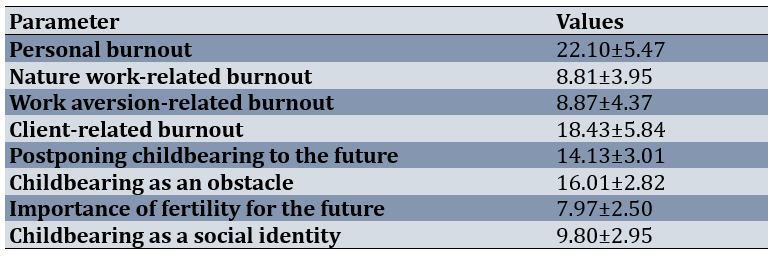

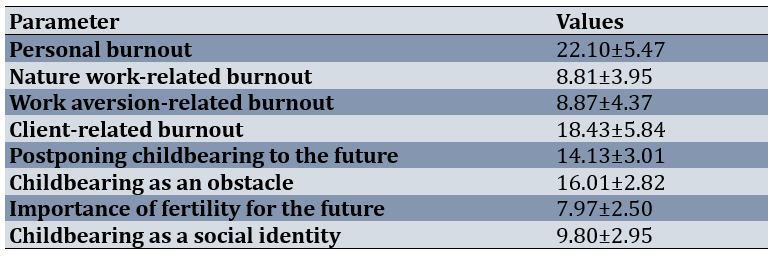

Among the burnout dimensions, personal burnout had the highest mean score (22.10±5.47), while nature work-related burnout exhibited the lowest mean score (8.81±3.95). In terms of attitudes toward childbearing, participants scored highest on the dimension of childbearing as an obstacle (16.01±2.82) and lowest on the importance of fertility for the future (7.97±2.50; Table 1).

Table 1. Mean scores of dimensions of burnout and attitudes toward childbearing

Correlation between burnout and childbearing attitudes

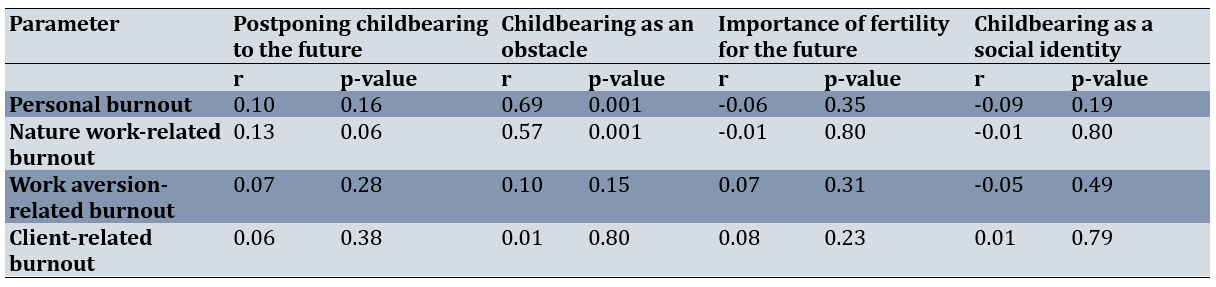

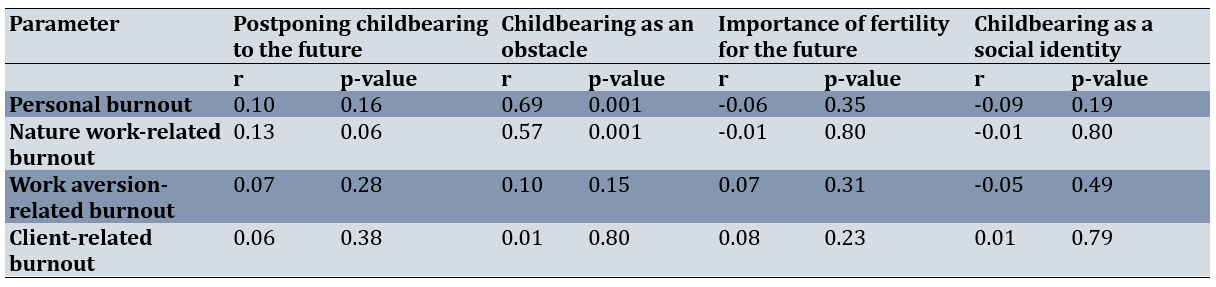

Personal burnout was strongly correlated with childbearing as an obstacle (r=0.69, p<0.001). A significant and positive correlation was also found between the nature of work-related burnout and childbearing as an obstacle (r=0.57, p<0.001). No significant relationships were observed between the burnout dimensions and the importance of fertility for the future or childbearing as a social identity. Similarly, the correlations between work-aversion-related burnout and client-related burnout with childbearing attitudes were weak and statistically insignificant (p>0.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Correlation between dimensions of burnout and attitudes toward childbearing

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between burnout and childbearing attitudes among female pediatric nurses. There was a strong correlation between personal burnout and the perception of childbearing as an obstacle. This finding highlights that burnout can alter perceptions of parenthood. Our findings support the notion that job burnout can influence family-related decisions and make long-term commitments, such as parenthood, seem overwhelming. Personal burnout reflects the accumulation of physical and psychological fatigue, leaving individuals feeling depleted and unable to manage additional responsibilities [35]. For nurses experiencing personal burnout, the thought of balancing professional duties with the demands of parenthood may seem unmanageable. As a result, childbearing is perceived as a hindrance rather than a meaningful or desirable life event.

Childbearing demands a substantial amount of time and energy, which can contribute to increased work-family conflict and, ultimately, burnout [39, 40]. Several studies have identified work-family conflict as a primary contributor to burnout among nurses [41, 42]. Furthermore, many individuals perceive childbearing as a hindrance to career advancement [32, 43]. Consistent with our results, a study conducted in Bushehr province, Iran, on employed married women reported that burnout is directly associated with work-family conflict, suggesting that burnout may exacerbate challenges in balancing professional responsibilities and family life [44]. Additionally, there is a direct and significant relationship between work-family conflict and burnout among nurses in Iran [41]. It is also important to note that the intention to have children requires mental resources, such as hope, optimism, and good mental health, all of which can be negatively affected by burnout. Supporting our results, a study conducted in Greece reported that burnout can significantly reduce hope among healthcare providers [45]. The negative effect of burnout on optimism among nurses has been reported [46]. Also, burnout can deteriorate the mental health of nurses [47].

The significant correlation between the nature of work-related burnout and childbearing as an obstacle underscores the challenges faced by pediatric nurses. Our results suggest that the nature of work-related burnout, which arises from the high demands and stressors specific to pediatric care, can make nurses feel overwhelmed, contributing to a sense of incapacity to take on additional responsibilities like parenting. According to a qualitative study, pediatric nurses experience burnout due to several challenges of pediatric care, including emotional exhaustion from caring for critically ill children and compassion fatigue [48]. Compassion fatigue, which can arise from caring for pediatric patients, is prevalent in pediatric nursing. Consistent with our results, findings from a systematic review indicated a significant link between compassion fatigue and burnout among pediatric nurses [49].

No significant correlations were found between burnout dimensions and other reproductive attitudes, such as the importance of fertility for the future or childbearing as a component of social identity. Thus, burnout may primarily influence immediate and practical concerns (such as the feasibility of parenthood) rather than long-term reproductive goals or symbolic views of parenthood.

The absence of a significant correlation between client-related burnout and negative childbearing attitudes is also noteworthy. Client-related burnout, which arises from interactions with patients and families, may not negatively influence personal decisions about childbearing. One possible explanation is that caring for pediatric patients may reinforce feelings of empathy and dedication to children. This could foster a sense of motherhood among pediatric nurses, allowing them to view their caregiving role as a source of personal fulfillment. This finding underscores the complexity of burnout, indicating that different sources of burnout may influence personal life choices in diverse ways.

Our findings carry important implications for healthcare institutions and policymakers, especially in contexts like Iran, where declining fertility rates are a growing concern. Based on our findings, addressing burnout among nurses is essential not only for improving their psychological well-being but also for supporting their family aspirations. High levels of burnout can lead nurses to perceive childbearing as an added burden, which may discourage them from having or expanding families. Healthcare institutions should develop strategies to reduce occupational stress. Potential measures include flexible work schedules and mental health support services. Such interventions can alleviate personal and work-related burnout, reducing the perceived conflict between professional and personal life responsibilities. By supporting nurses in balancing their roles, healthcare institutions can indirectly foster a more positive outlook toward childbearing and family formation.

The strengths of this study lie in its use of reliable and validated measurement tools, which enhance the accuracy and reliability of the data collected. Furthermore, the study’s sample size was determined based on a 95% confidence level and 80% statistical power, ensuring that the results are statistically significant and that the analysis has sufficient power to detect meaningful correlations. Additionally, the focus on female pediatric nurses addresses an important gap in the literature, as this demographic has been underrepresented in previous research. By investigating burnout and attitudes toward childbearing among this group, the study contributes valuable insights into the unique challenges faced by pediatric nurses.

However, there are several limitations to consider. The study used a convenience sampling method, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The sample was drawn from two hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and the results may not be applicable to nurses working in other regions or healthcare settings. A more randomized sampling technique could improve the external validity of the study and allow for broader generalizations. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of response bias, as participants may not fully disclose their experiences or may provide answers that align with social expectations.

Future research should also investigate the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce burnout and their impact on reproductive attitudes. For example, studies could examine whether nurses who participate in stress management programs are more likely to develop positive attitudes toward childbearing. Additionally, qualitative research could provide deeper insights into the personal experiences of nurses and how they navigate the challenges of balancing work and family life.

Our findings suggest that the emotional and psychological toll of caregiving roles in pediatric nursing can shape attitudes toward childbearing, often making it seem like an obstacle. The different dimensions of burnout appear to impact reproductive decisions in various ways, as evidenced by the lack of association between client-related burnout and childbearing attitudes. This complexity underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of how occupational stress and burnout influence personal life choices among healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

There is a significant relationship between burnout and childbearing attitudes among female pediatric nurses, with personal and nature of work-related burnout strongly associated with the perception of childbearing as an obstacle.

Acknowledgments: The research team extends its gratitude to all those who contributed to the writing and publication of this study. We would like to particularly acknowledge the participants for their valuable input. Special thanks go to the Tehran University of Medical Sciences for the support and facilitation of this research. We also express our sincere appreciation to Mrs. Mirzakhani and Dr. Begjani for their assistance throughout the study.

Ethical Permissions: This study adhered to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and the Helsinki Declaration of Ethics. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1402.227). Participants were fully informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, and written informed consent was obtained before participation. Individuals were informed that their participation was voluntary and that there would be no negative consequences for not participating in this study. The anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were maintained.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Sadat Hosseini AS (First Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer (25%); Alviri S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (15%); Pakzad P (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (15%); Rostamian F (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher (15%); Rajabi MM (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%)

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

A young population is a critical driver of a nation’s economic growth and societal development. As the primary contributors to the labor force, young individuals bring innovation and energy to various sectors, thereby fostering economic advancement and technological progress [1, 2]. In contrast, an aging population presents significant challenges, including increased healthcare costs, strained pension systems, and reduced workforce availability, which can slow economic growth and innovation [3, 4].

In recent decades, fertility rates have declined worldwide, becoming a critical concern for governments, policymakers, and researchers [5]. Many countries, including Iran, are witnessing below-replacement fertility rates, which puts them at risk of an aging population. This demographic shift poses a serious hindrance to the country’s development [6]. A recent study revealed that the total fertility rate (TFR) in Tehran, Iran, has experienced a notable decline. The results indicated a steep downward trend over the next decade, with the TFR decreasing from 1.4 children per woman in 2019 to an estimated 1.06 children per woman by 2029 [7]. Social, cultural, and economic changes have altered the way people view marriage, parenthood, and family life [8, 9]. Shifts in gender roles, financial instability, delayed marriages, and the pursuit of higher education and careers (particularly among women) have contributed to reduced fertility rates [10-12]. In Iran, where the fertility rate has dropped dramatically over the past few decades, concerns about the population’s long-term sustainability have become a national priority [13].

Healthcare professionals, especially nurses, constitute a substantial part of the working population in every society, making their attitudes toward fertility a critical factor in shaping population dynamics [14, 15]. Nurses face unique challenges in balancing personal and professional life, which can significantly influence their family decisions [16]. In pediatric nursing, the situation is even more complex. These nurses spend much of their time caring for children and interacting with families, which profoundly shapes their perspectives on parenthood [17, 18]. On the one hand, close exposure to children may naturally inspire a strong desire for parenthood among pediatric nurses. On the other hand, the emotional and physical demands of their profession can lead to burnout, which may negatively affect their attitudes toward childbearing.

Burnout, a psychological condition resulting from prolonged occupational stress, is a prevalent issue among healthcare workers, particularly those in high-pressure environments like pediatric units [19-21]. A systematic review revealed that the prevalence of burnout syndrome among pediatric intensive care unit nurses ranges from 42% to 77% [22]. Also, 38.6% of pediatric Spanish nurses have high levels of burnout [23]. Pediatric nurses encounter burnout due to the emotional and physical demands of their role. Caring for critically ill children, supporting distressed families, and witnessing suffering or loss can lead to emotional exhaustion and ultimately burnout [24-26]. Long hours, high workloads, and staffing shortages further exacerbate the issue, making pediatric nurses particularly vulnerable to burnout [27, 28].

Studies have revealed that burnout can significantly affect the professional performance and attitudes of nurses. There is a significant inverse relationship between missed nursing care and job burnout in nurses in Iran, suggesting that higher levels of burnout are associated with an increased likelihood of missed nursing care [29]. According to a systematic review, burnout may negatively impact pediatric nurses’ attitudes toward patient safety in acute hospital settings [21]. Another study conducted in Iraq reported that higher levels of burnout are significantly associated with an increased intention to leave the nursing profession [30]. Given the significant impact of burnout on nurses’ professional decisions, it is reasonable to posit that burnout may also influence personal life decisions, including family-related choices such as childbearing.

Burnout can reduce the emotional and mental resources necessary for envisioning and managing parenthood. For many nurses, the thought of taking on additional caregiving responsibilities at home can seem overwhelming [31-33]. Consequently, they may develop negative or ambivalent attitudes toward childbearing, leading to delays in starting a family or choosing not to have children at all. Nurses experiencing burnout might view parenthood as an additional source of stress rather than a fulfilling life goal [32, 34].

The relationship between burnout and childbearing attitudes is an underexplored area of research, particularly among pediatric nurses. Developing strategies to support nurses’ family decisions is essential, not only for improving their quality of life but also for addressing broader concerns about population trends and fertility rates in Iran and beyond. Given the high levels of burnout in nurses’ work and the declining fertility trends globally and in Iran, it is crucial to understand how occupational burnout influences reproductive intentions. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between burnout and attitudes toward childbearing among female pediatric nurses.

Instrument and Methods

Study design, Subjects, and setting

This correlational study assessed female nurses employed at selected pediatric hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, including the Children’s Medical Center and Bahrami Hospitals, in 2024. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria included voluntary participation, being a married female nurse with at least a bachelor’s degree, and having a minimum of six months of clinical experience. Nurses who did not answer more than 10% of the questions were excluded from the study.

Sample size

To calculate the sample size, a 95% confidence level and 80% statistical power were applied, with an assumed minimum correlation coefficient of 0.20 between the variables. The minimum required sample size was determined to be 194 participants using the following equation:

Research tools

Data were collected using a demographic information form, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, and the Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing Scale. The questionnaires were distributed to participants in person during their shifts. To ensure a high response rate and accurate data collection, the research team was available to address any questions or concerns during the completion of the questionnaire.

Demographic information form: This form collected information, such as age, number of children, average number of shifts per month, and level of education.

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: This tool was developed by Kristensen et al. in 2005 and consists of 19 items across three dimensions, including personal burnout (six items, total score ranging from 0 to 30), work-related burnout (seven items, total score ranging from 0 to 35), and client-related burnout (six items, total score ranging from 0 to 30). Each dimension is evaluated separately, with no overall score calculated. Responses are provided on a five-point Likert scale, where zero indicates “never” or “very low degree,” and five represents “always” or "very high degree” [35].

Mahmoudi et al. validated the Persian version of the inventory, maintaining the 19-item structure but dividing it into four dimensions, namely personal burnout (seven items, total score ranging from zero to 35), nature of work-related burnout (three items, total score ranging from zero to 15), work-aversion-related burnout (three items, total score ranging from zero to 15), and client-related burnout (six items, total score ranging from zero to 30). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the dimensions ranged between 0.84 and 0.89, confirming the reliability of the tool [36]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the dimensions of personal burnout, nature of work-related burnout, work-aversion-related burnout, and client-related burnout were 0.86, 0.83, 0.86, and 0.87, respectively, confirming the reliability of this tool.

Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing Scale: This scale was originally developed by Söderberg et al. in 2013. It comprises 27 items across three dimensions, namely the significance of fertility for the future (nine items, total score ranging from nine to 45), childbearing as a present barrier (12 items, total score ranging from 12 to 60), and childbearing as part of social identity (six items, total score ranging from six to 30). Each dimension is scored independently, without generating an overall score. Responses are rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating stronger agreement with the respective dimension [37]. Kordzanganeh and Mohammadian validated the Persian version of this scale, which includes 20 items divided into four dimensions, including postponing childbearing to a future time (five items, total score ranging from five to 25), childbearing as a hindrance (five items, total score ranging from five to 25), fertility as a future goal (six items, total score ranging from six to 30), and childbearing as social identity (four items, total score ranging from four to 20). They also reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 for the Persian version, confirming its reliability [38]. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the dimensions of postponing childbearing to a future time, childbearing as a hindrance, fertility as a future goal, and childbearing as a social identity were 0.85, 0.87, 0.84, and 0.86, respectively, confirming the reliability of the tool.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software 16. Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation, were used alongside inferential statistics, including Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed the normal distribution of the data. A significance level of p<0.05 was set to determine statistical significance.

Findings

Demographic characteristics

A total of 194 female pediatric nurses participated in the study. The participants had an average age of 33.26±7.00 years, and most held a bachelor’s degree (86.1%), while 13.9% held a master’s degree or higher. On average, the nurses had one child (1.00±0.56) and worked 26.99±1.83 shifts per month.

Descriptive statistics of burnout and childbearing attitudes

Among the burnout dimensions, personal burnout had the highest mean score (22.10±5.47), while nature work-related burnout exhibited the lowest mean score (8.81±3.95). In terms of attitudes toward childbearing, participants scored highest on the dimension of childbearing as an obstacle (16.01±2.82) and lowest on the importance of fertility for the future (7.97±2.50; Table 1).

Table 1. Mean scores of dimensions of burnout and attitudes toward childbearing

Correlation between burnout and childbearing attitudes

Personal burnout was strongly correlated with childbearing as an obstacle (r=0.69, p<0.001). A significant and positive correlation was also found between the nature of work-related burnout and childbearing as an obstacle (r=0.57, p<0.001). No significant relationships were observed between the burnout dimensions and the importance of fertility for the future or childbearing as a social identity. Similarly, the correlations between work-aversion-related burnout and client-related burnout with childbearing attitudes were weak and statistically insignificant (p>0.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Correlation between dimensions of burnout and attitudes toward childbearing

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between burnout and childbearing attitudes among female pediatric nurses. There was a strong correlation between personal burnout and the perception of childbearing as an obstacle. This finding highlights that burnout can alter perceptions of parenthood. Our findings support the notion that job burnout can influence family-related decisions and make long-term commitments, such as parenthood, seem overwhelming. Personal burnout reflects the accumulation of physical and psychological fatigue, leaving individuals feeling depleted and unable to manage additional responsibilities [35]. For nurses experiencing personal burnout, the thought of balancing professional duties with the demands of parenthood may seem unmanageable. As a result, childbearing is perceived as a hindrance rather than a meaningful or desirable life event.

Childbearing demands a substantial amount of time and energy, which can contribute to increased work-family conflict and, ultimately, burnout [39, 40]. Several studies have identified work-family conflict as a primary contributor to burnout among nurses [41, 42]. Furthermore, many individuals perceive childbearing as a hindrance to career advancement [32, 43]. Consistent with our results, a study conducted in Bushehr province, Iran, on employed married women reported that burnout is directly associated with work-family conflict, suggesting that burnout may exacerbate challenges in balancing professional responsibilities and family life [44]. Additionally, there is a direct and significant relationship between work-family conflict and burnout among nurses in Iran [41]. It is also important to note that the intention to have children requires mental resources, such as hope, optimism, and good mental health, all of which can be negatively affected by burnout. Supporting our results, a study conducted in Greece reported that burnout can significantly reduce hope among healthcare providers [45]. The negative effect of burnout on optimism among nurses has been reported [46]. Also, burnout can deteriorate the mental health of nurses [47].

The significant correlation between the nature of work-related burnout and childbearing as an obstacle underscores the challenges faced by pediatric nurses. Our results suggest that the nature of work-related burnout, which arises from the high demands and stressors specific to pediatric care, can make nurses feel overwhelmed, contributing to a sense of incapacity to take on additional responsibilities like parenting. According to a qualitative study, pediatric nurses experience burnout due to several challenges of pediatric care, including emotional exhaustion from caring for critically ill children and compassion fatigue [48]. Compassion fatigue, which can arise from caring for pediatric patients, is prevalent in pediatric nursing. Consistent with our results, findings from a systematic review indicated a significant link between compassion fatigue and burnout among pediatric nurses [49].

No significant correlations were found between burnout dimensions and other reproductive attitudes, such as the importance of fertility for the future or childbearing as a component of social identity. Thus, burnout may primarily influence immediate and practical concerns (such as the feasibility of parenthood) rather than long-term reproductive goals or symbolic views of parenthood.

The absence of a significant correlation between client-related burnout and negative childbearing attitudes is also noteworthy. Client-related burnout, which arises from interactions with patients and families, may not negatively influence personal decisions about childbearing. One possible explanation is that caring for pediatric patients may reinforce feelings of empathy and dedication to children. This could foster a sense of motherhood among pediatric nurses, allowing them to view their caregiving role as a source of personal fulfillment. This finding underscores the complexity of burnout, indicating that different sources of burnout may influence personal life choices in diverse ways.

Our findings carry important implications for healthcare institutions and policymakers, especially in contexts like Iran, where declining fertility rates are a growing concern. Based on our findings, addressing burnout among nurses is essential not only for improving their psychological well-being but also for supporting their family aspirations. High levels of burnout can lead nurses to perceive childbearing as an added burden, which may discourage them from having or expanding families. Healthcare institutions should develop strategies to reduce occupational stress. Potential measures include flexible work schedules and mental health support services. Such interventions can alleviate personal and work-related burnout, reducing the perceived conflict between professional and personal life responsibilities. By supporting nurses in balancing their roles, healthcare institutions can indirectly foster a more positive outlook toward childbearing and family formation.

The strengths of this study lie in its use of reliable and validated measurement tools, which enhance the accuracy and reliability of the data collected. Furthermore, the study’s sample size was determined based on a 95% confidence level and 80% statistical power, ensuring that the results are statistically significant and that the analysis has sufficient power to detect meaningful correlations. Additionally, the focus on female pediatric nurses addresses an important gap in the literature, as this demographic has been underrepresented in previous research. By investigating burnout and attitudes toward childbearing among this group, the study contributes valuable insights into the unique challenges faced by pediatric nurses.

However, there are several limitations to consider. The study used a convenience sampling method, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The sample was drawn from two hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and the results may not be applicable to nurses working in other regions or healthcare settings. A more randomized sampling technique could improve the external validity of the study and allow for broader generalizations. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of response bias, as participants may not fully disclose their experiences or may provide answers that align with social expectations.

Future research should also investigate the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce burnout and their impact on reproductive attitudes. For example, studies could examine whether nurses who participate in stress management programs are more likely to develop positive attitudes toward childbearing. Additionally, qualitative research could provide deeper insights into the personal experiences of nurses and how they navigate the challenges of balancing work and family life.

Our findings suggest that the emotional and psychological toll of caregiving roles in pediatric nursing can shape attitudes toward childbearing, often making it seem like an obstacle. The different dimensions of burnout appear to impact reproductive decisions in various ways, as evidenced by the lack of association between client-related burnout and childbearing attitudes. This complexity underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of how occupational stress and burnout influence personal life choices among healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

There is a significant relationship between burnout and childbearing attitudes among female pediatric nurses, with personal and nature of work-related burnout strongly associated with the perception of childbearing as an obstacle.

Acknowledgments: The research team extends its gratitude to all those who contributed to the writing and publication of this study. We would like to particularly acknowledge the participants for their valuable input. Special thanks go to the Tehran University of Medical Sciences for the support and facilitation of this research. We also express our sincere appreciation to Mrs. Mirzakhani and Dr. Begjani for their assistance throughout the study.

Ethical Permissions: This study adhered to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and the Helsinki Declaration of Ethics. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1402.227). Participants were fully informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, and written informed consent was obtained before participation. Individuals were informed that their participation was voluntary and that there would be no negative consequences for not participating in this study. The anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were maintained.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Sadat Hosseini AS (First Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer (25%); Alviri S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (15%); Pakzad P (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (15%); Rostamian F (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher (15%); Rajabi MM (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%)

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Mahtta R, Fragkias M, Güneralp B, Mahendra A, Reba M, Wentz EA, et al. Urban land expansion: The role of population and economic growth for 300+ cities. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2022;2(1):5. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s42949-022-00048-y]

2. Peterson EWF. The role of population in economic growth. Sage Open. 2017;7(4):2158244017736094. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2158244017736094]

3. Sander M, Oxlund B, Jespersen A, Krasnik A, Mortensen EL, Westendorp RG, et al. The challenges of human population ageing. Age Ageing. 2014;44(2):185-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afu189]

4. Khan HTA, Addo KM, Findlay H. Public health challenges and responses to the growing ageing populations. Public Health Chall. 2024;3(3):e213. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/puh2.213]

5. Skakkebæk NE, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Levine H, Andersson AM, Jørgensen N, Main KM, et al. Environmental factors in declining human fertility. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(3):139-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41574-021-00598-8]

6. Asadisarvestani K, Sobotka T. A pronatalist turn in population policies in Iran and its likely adverse impacts on reproductive rights, health and inequality: A critical narrative review. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2023;31(1):2257075. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/26410397.2023.2257075]

7. Esmaeili N, Abbasi Shavazi MJ. Impact of family policies and economic situation on low fertility in Tehran, Iran: A multi-agent-based modeling. Demogr Res. 2024;51(5):107-54. [Link] [DOI:10.4054/DemRes.2024.51.5]

8. Smith DJ. Masculinity, money, and the postponement of parenthood in Nigeria. Popul Dev Rev. 2020;46(1):101-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/padr.12310]

9. Nomaguchi K, Milkie MA. Parenthood and well-being: A decade in review. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82(1):198-223. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jomf.12646]

10. Paksi V, Nagy B, Tardos K. Perceptions of barriers to motherhood: Female STEM PhD students' changing family plans. Soc Incl. 2022;10(3):149-59. [Link] [DOI:10.17645/si.v10i3.5250]

11. Yu X, Liang J. Social norms and fertility intentions: Evidence from China. Front Psychol. 2022;13:947134. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.947134]

12. Bellés-Obrero C, Cabrales A, Jiménez-Martín S, Vall-Castelló J. Women's education, fertility and children' health during a gender equalization process: Evidence from a child labor reform in Spain. Eur Econ Rev. 2023;154:104411. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2023.104411]

13. Doshmangir L, Khabiri R, Gordeev VS. Policies to address the impact of an ageing population in Iran. Lancet. 2023;401(10382):1078. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00179-4]

14. Galanis P, Moisoglou I, Katsiroumpa A, Vraka I, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, et al. Increased job burnout and reduced job satisfaction for nurses compared to other healthcare workers after the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Rep. 2023;13(3):1090-100. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nursrep13030095]

15. Salmani N, Talebnayyeri F, Kamal Nooshabadi l, Shafihosseini Z. Investigate the attitudes of nurses about fertility and childbearing in 2023: A descriptive survey in Meybod and Ardakan cities. Sci J Nurs Midwifery Paramed Fac. 2024;10(1):14-28. [Persian] [Link]

16. Ahmadzadeh-Zeidi MJ, Rooddehghan Z, Haghani S. The relationship between work-family conflict and missed nursing care; A cross-sectional study in Iran. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):869. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12912-024-02556-x]

17. Done RDG, Oh J, Im M, Park J. Pediatric nurses' perspectives on family-centered care in Sri Lanka: A mixed-methods study. Child Health Nurs Res. 2020;26(1):72-81. [Link] [DOI:10.4094/chnr.2020.26.1.72]

18. Razeq NMA, Arabiat DH, Shields L. Nurses' perceptions and attitudes toward family-centered care in acute pediatric care settings in Jordan. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;61:207-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2021.05.018]

19. De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: Prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Local Reg Anesth. 2020;13:171-83. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/LRA.S240564]

20. Nolan G, Dockrell L, Crowe S. Burnout in the paediatric intensive care unit. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2020;8(4):184-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40124-020-00228-3]

21. Flynn C, Watson C, Patton D, O'Connor T. The impact of burnout on paediatric nurses' attitudes about patient safety in the acute hospital setting: A systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;78:e82-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2024.06.023]

22. Matsuishi Y, Mathis BJ, Masuzawa Y, Okubo N, Shimojo N, Hoshino H, et al. Severity and prevalence of burnout syndrome in paediatric intensive care nurses: A systematic review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;67:103082. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103082]

23. De La Fuente-Solana EI, Pradas-Hernández L, González-Fernández CT, Velando-Soriano A, Martos-Cabrera MB, Gómez-Urquiza JL, et al. Burnout syndrome in paediatric nurses: A multi-centre study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1324. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18031324]

24. Rico-Mena P, Güeita-Rodríguez J, Martino-Alba R, Castel-Sánchez M, Palacios-Ceña D. The emotional experience of caring for children in pediatric palliative care: A qualitative study among a home-based interdisciplinary care team. Children. 2023;10(4):700. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/children10040700]

25. Mu PF, Tseng YM, Wang CC, Chen YJ, Huang SH, Hsu TF, et al. Nurses' experiences in end-of-life care in the PICU: A qualitative systematic review. Nurs Sci Q. 2019;32(1):12-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0894318418807936]

26. Anguis Carreño M, Marín Yago A, Jurado Bellón J, Baeza-Mirete M, Muñoz-Rubio GM, Rojo Rojo A. An exploratory study of ICU pediatric nurses' feelings and coping strategies after experiencing children death. Healthcare. 2023;11(10):1460. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare11101460]

27. Liao H, Liang R, He H, Huang Y, Liu M. Work stress, burnout, occupational commitment, and social support among Chinese pediatric nurses: A moderated mediation model. J Pediatr Nur. 2022;67:e16-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2022.10.009]

28. Buckley L, Berta W, Cleverley K, Medeiros C, Widger K. What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: A scoping review. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):9. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12960-020-0451-8]

29. Begjani J, Jafari M, Khajezadeh A, Rajabi MM. The relationship between job burnout and missed nursing care in nurses from the selected hospitals in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Nurs. 2024;37(147):78-89. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/ijn.37.147.3348.9]

30. Karimi Rozveh A, Sayadi L, Hajibabaee F, Alzubaidi SSI. Relationship between intention to leave with job satisfaction and burnout of nurses in Iraq: A cross-sectional correlational study. J Multidiscip Care. 2023;12(1):39-45. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/jmdc.1222]

31. Ren X, Cai Y, Wang J, Chen O. A systematic review of parental burnout and related factors among parents. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):376. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-024-17829-y]

32. Torres AJC, Barbosa-Silva L, Oliveira-Silva LC, Miziara OPP, Guahy UCR, Fisher AN, et al. The impact of motherhood on women's career progression: A scoping review of evidence-based interventions. Behav Sci. 2024;14(4):275. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/bs14040275]

33. Ong P, Cong X, Yeo Y, Shorey S. Experiences of nurses managing parenthood and career: A systematic review and meta‐synthesis. Int Nurs Rev. 2024;71(3):610-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/inr.12885]

34. Mohammadi F, Bijani M, Borzou SR, Oshvandi K, Khazaei S, Bashirian S. Resilience, occupational burnout, and parenting stress in nurses caring for COVID-19 patients. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol. 2021;16(3):116-23. [Link] [DOI:10.5114/nan.2021.113311]

35. Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The copenhagen burnout inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. 2005;19(3):192-207. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/02678370500297720]

36. Mahmoudi S, Atashzadeh-Shoorideh F, Rassouli M, Moslemi A, Pishgooie AH, Azimi H. Translation and psychometric properties of the Copenhagen burnout inventory in Iranian nurses. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2017;22(2):117-22. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1735-9066.205958]

37. Söderberg M, Lundgren I, Christensson K, Hildingsson I. Attitudes toward fertility and childbearing scale: An assessment of a new instrument for women who are not yet mothers in Sweden. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):197. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-13-197]

38. Kordzanganeh J, Mohamadian H. Psychometric assessment of the validity of the Iranian version of attitude toward fertility and childbearing inventory in women without a history of pregnancy in the south of Iran. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2019;17(1):83-94. [Persian] [Link]

39. Nomaguchi K, Fettro MN. Childrearing stages and work-family conflict: The role of job demands and resources. J Marriage Fam. 2018;81(2):289-307. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jomf.12521]

40. Richter A, Schraml K, Leineweber C. Work-family conflict, emotional exhaustion and performance-based self-esteem: Reciprocal relationships. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(1):103-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00420-014-0941-x]

41. Yarifard K, Abravesh A, Sokhanvar M, Mehrtak M, Mousazadeh Y. Work-family conflict, burnout, and related factors among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Northwest of Iran. Work. 2023;76(1):47-59. [Link] [DOI:10.3233/WOR-220210]

42. Fang YX. Burnout and work-family conflict among nurses during the preparation for reevaluation of a grade A tertiary hospital. Chin Nurs Res. 2017;4(1):51-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cnre.2017.03.010]

43. Gallardo M. Does maternity affect women's careers? Perceptions of working mothers in academia. EDUCACIÓN XX1. 2021;24(1):405-28. [Link] [DOI:10.5944/educxx1.26714]

44. Bagherzadeh R, Taghizadeh Z, Mohammadi E, Kazemnejad A, Pourreza A, Ebadi A. Relationship of work-family conflict with burnout and marital satisfaction: Cross-domain or source attribution relations?. Health Promot Perspect. 2016;6(1):31-6. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/hpp.2016.05]

45. Theofilou P, Platis C, Madia K, Kotsiopoulos I. Burnout and optimism among health workers during the period of COVID-19. South East Eur J Public Health. 2023;1. [Link] [DOI:10.56801/seejph.vi.250]

46. Malagón-Aguilera MC, Suñer-Soler R, Bonmatí-Tomas A, Bosch-Farré C, Gelabert-Viella S, Fontova-Almató A, et al. Dispositional optimism, burnout and their relationship with self-reported health status among nurses working in long-term healthcare centers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4918. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17144918]

47. Asheghi H, Asheghi M, Hesari M. Mediation role of psychological capital between job stress, burnout, and mental health among nurses. Pract Clin Psychol. 2020;8(2):99-108. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.8.2.716.1]

48. Bian W, Cheng J, Dong Y, Xue Y, Zhang Q, Zheng Q, et al. Experience of pediatric nurses in nursing dying children-a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):126. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12912-023-01274-0]

49. Forsyth LA, Lopez S, Lewis KA. Caring for sick kids: An integrative review of the evidence about the prevalence of compassion fatigue and effects on pediatric nurse retention. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;63:9-19. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2021.12.010]