Volume 6, Issue 2 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(2): 65-69 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.YUMS.REC.1398.125

History

Received: 2025/05/7 | Accepted: 2025/06/12 | Published: 2025/06/18

Received: 2025/05/7 | Accepted: 2025/06/12 | Published: 2025/06/18

How to cite this article

Zoladl M, Mousavi M, Rastian M, Tabatabaei F, Salari M. Effect of Patient Safety Culture on the Nurses' Professional Behavior. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (2) :65-69

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-404-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-404-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- Department of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Nursing, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

3- Student Research Committee, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- Department of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Nursing, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

3- Student Research Committee, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (801 Views)

Introduction

Across the globe, healthcare leaders continue to face a complex set of challenges in delivering high-quality care. Patient safety and the quality of care are two of the most pressing concerns in global health systems [1]. Today, medical errors frequently result in patient harm and, in many cases, even death. These errors—such as medication mistakes, delayed referrals, and inadequate follow-up—occur with concerning regularity and directly impact patient safety [2].

Nursing activities are closely tied to patient safety. For example, nurses play key roles in medication administration, infection control, and fall prevention. As such, their efforts to promote patient safety are vital [3]. To implement effective safety strategies, healthcare organizations must adopt a “safety culture” model [4]. One definition of patient safety culture is “an organization’s willingness and ability to understand safety (and its risks), as well as its willingness and ability to act toward safety” [5].

Patient safety culture reflects the level of commitment, leadership style, and competency within healthcare institutions. The development of this culture can be influenced by the professional behavior of healthcare staff—behavior that is itself shaped by organizational management [6]. Professional behavior is a fundamental concept in nursing, referring to adherence to specific behavioral standards that improve care performance. It is essential for the effective execution of nursing duties and is directly linked to both performance outcomes and patient results [7]. Education in patient safety culture plays an important role in medical sciences by promoting proactive engagement in identifying and addressing patient safety issues [8].

Agbar et al. state that patient safety programs can positively influence and improve the culture of safety among healthcare personnel [9]. Similarly, Rahimi et al. found that patient safety culture should be integrated into quality and safety improvement initiatives in patient care. They emphasize the need for non-punitive safety policies, staff support, and effective educational programs in hospitals [10].

Despite the recognized importance of patient safety culture, few studies have directly and purposefully investigated its impact on the professional behavior of nurses in clinical settings. Most existing research has been descriptive and has not employed randomized controlled designs. This highlights a clear need for further investigation into the effects of safety culture on the professional behavior of nurses. The lack of definitive and reliable evidence in this area has created a gap in the literature. The present study aimed to address this gap and provide scientific evidence on the subject. Therefore, this research was conducted to determine the effect of patient safety culture on nurses’ professional behavior.

Materials and Methods

This interventional, controlled field trial was conducted in 2021 on 84 nurses working in hospitals affiliated with Yasuj University of Medical Sciences. Participants were selected through convenience sampling and were randomly assigned using block randomization into two equal groups, including the intervention (n=42) and control (n=42) groups.

The sample size was calculated using G*Power software version 3.1.9.7, considering a type I error (alpha) of 0.01, a confidence level of 99%, a type II error (beta) of 0.10, and a test power of 90%. Based on these parameters, the required number of participants in each group was calculated to be 34.63. Accounting for a 20% potential dropout rate, the final sample size was determined to be 42 participants per group, totaling 84 participants.

Inclusion criteria included having a bachelor’s or master’s degree in nursing, the ability to communicate and respond to questions, willingness to participate in the study, and active employment in a teaching hospital. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to continue participation, prior involvement in similar studies within the last six months, and obtaining a score of 64 or higher on the Nursing Students Professional Behaviors Scale (NSPBS).

Data were collected using a demographic information form and the NSPBS.

The NSPBS was developed by Goz and Geckil in 2010 to assess the professional behaviors of nursing students. It contains 27 items covering three dimensions, namely health care practices (items 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 16-21, 23, 25-27), activity practices (items 2, 5, 7, 11, 13-15), and reporting (items 22, 24). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). The total score ranges from 27 to 135, with higher scores indicating higher levels of professional nursing behavior [11]. The scale’s validity was confirmed by Heshmati Nabavi et al. in 2014, reporting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 for the overall scale [12]. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.69 to 0.80 across the subscales and was 0.71 for the total scale.

Data collection involved in-person interviews, during which participants were screened according to the inclusion criteria and signed informed consent forms. They were then provided with the demographic form and the NSPBS. The intervention was conducted in a designated room within one of the hospital wards affiliated with Yasuj University of Medical Sciences. Prior to the intervention, participants in the intervention group were briefed about group rules and responsibilities. The intervention sessions, conducted by the researcher in a group format, consisted of four 120-minute sessions over the course of one month. The control group did not receive any educational intervention. One month after the completion of the intervention, the professional behavior of the nurses was reassessed using the NSPBS.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 21, applying Chi-square tests, independent t-tests, and paired t-tests. A significance level of 0.01 was considered for all tests.

Findings

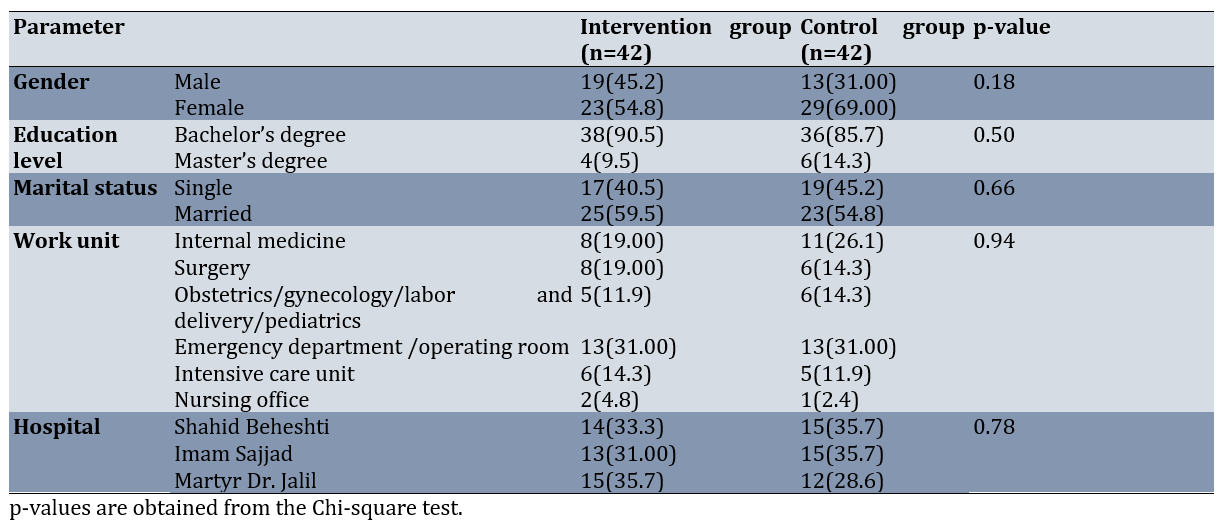

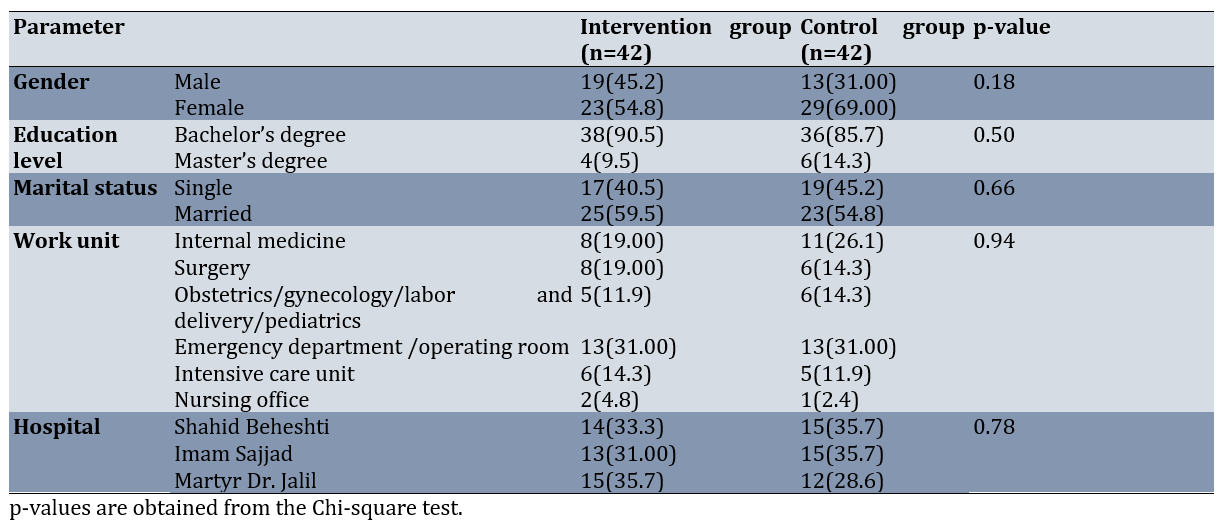

A total of 84 nurses participated in this study, and all remained until the end of the study. The mean age of the participants was 31.40±4.60 years. The mean age was 31.4±3.8 years in the intervention group and 31.4±5.4 years in the control group (p=0.89), while the mean work experience was 6.3±7.7 years in the intervention group and 6.3±6.5 years in the control group (p=0.93; Table 1)

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants

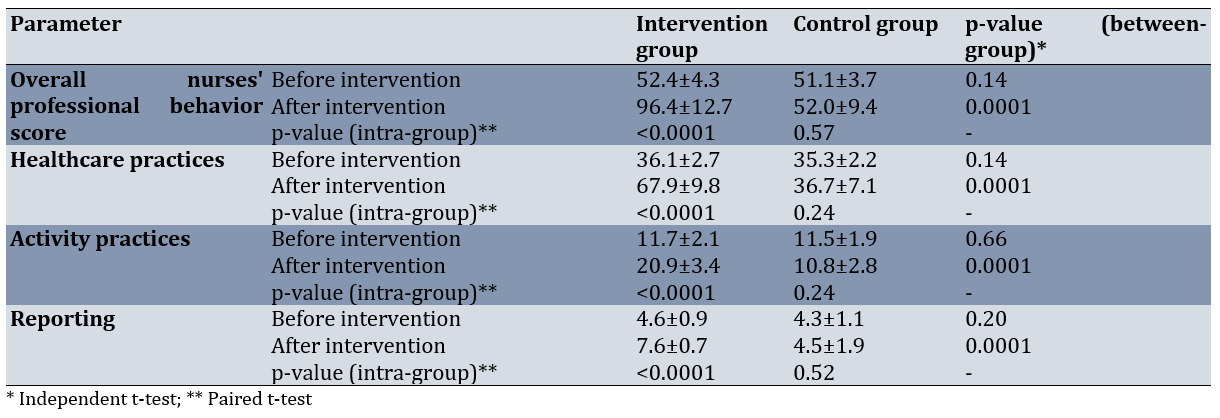

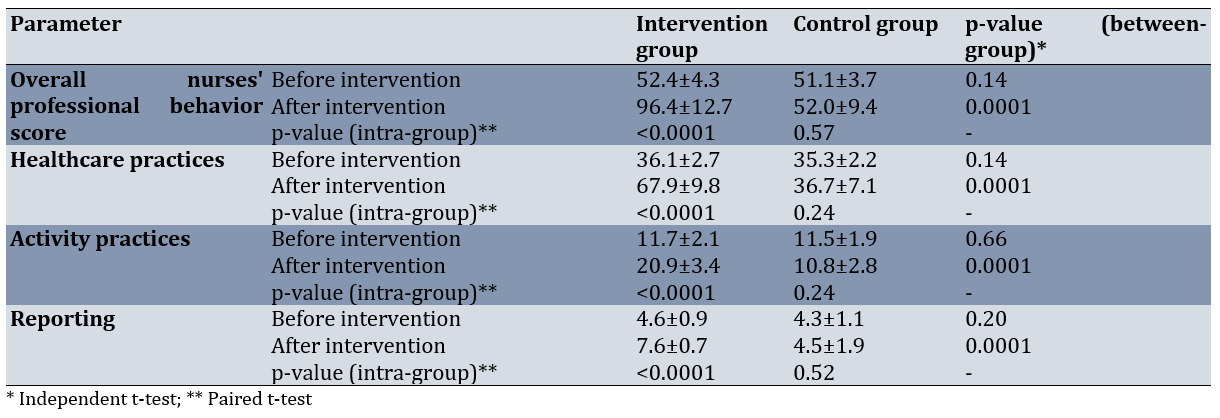

There was no statistically significant difference in mean overall professional behavior scores of the nurses and their subscales between the two groups before the intervention (p>0.05), indicating baseline similarity between the intervention and control groups. However, the between-group comparison after the intervention revealed a statistically significant difference in the mean scores of the overall professional behavior of the nurses and their subscales (p<0.0001).

Additionally, intra-group comparisons were conducted to examine changes within each group separately. There was a statistically significant improvement in the intervention group before and after the intervention (p<0.0001), while no significant change was observed in the control group (p>0.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the mean overall nurses' professional behavior scores and their subscales in both groups

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effect of patient safety culture on nurses’ professional behavior. One month after the intervention, the mean score of professional behavior of nurses in the intervention group increased significantly compared to the control group. Implementing a patient safety culture had a positive impact on enhancing the professional behavior of nurses, which aligns with the results of studies by Berry et al. [13], Sortedahl et al. [14], and Dyrbye et al. [15].

Similarly, Ayu Eka et al. emphasize the necessity for nurse educators to model professional behavior and actively promote a culture of professional nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure full presence and comprehensive care delivery [16], which is consistent with the present study. Furthermore, Lee and Kwon found that ensuring patient safety through the creation of safe work environments and fostering an organizational culture that prioritizes patient safety are essential steps to encourage nurses to raise concerns and openly discuss safety-related issues, including their own behaviors [17]. These findings also support the current study.

Measuring patient safety culture provides an opportunity to identify shared areas for quality improvement, reducing the likelihood of adverse events, and enhancing the overall quality of care. Moreover, quality improvement strategies are aligned with the promotion of patient safety culture within hospitals. Therefore, educational programs for healthcare professionals should incorporate more content related to patient safety, particularly emphasizing communication, leadership, non-punitive error reporting, quality improvement, and teamwork [18].

Based on our findings, it can be concluded that implementing a patient safety culture is both essential and impactful in promoting the professional behavior of nurses. Notably, this study also observed improvements in communication skills and teamwork capabilities among nurses following the intervention. In line with this, Yayeh et al. reported that caring behaviors among nurses are influenced by factors, such as professional satisfaction, job satisfaction, low workload, and good relationships with colleagues, all of which contribute to improved quality of nursing care [19]. Additionally, Masibo et al. found that professional performance in nursing is not gender-dependent and that nurses’ perceptions of their profession, institutional factors, and opportunities for professional development significantly impact their performance [20].

Among the strengths of this study are the selection of two critical factors (patient safety and professional behavior), both of which are vital to improving the quality of nursing services. Furthermore, the integration of safety and professional behavior concepts, which are often studied separately, adds value and novelty to this research.

However, the study also had limitations. One limitation was the use of self-report questionnaires to assess professional behaviors without incorporating complementary tools such as direct observation or performance evaluations. Another limitation was the possibility that the self-reported data might not fully reflect participants’ actual behaviors. Moreover, the study did not simultaneously assess other potential psychological or environmental factors that may influence professional behavior.

Given these findings, and considering that this study was conducted solely in teaching hospitals in Yasuj, it is recommended that similar research be carried out in other hospitals across the country. Since the participants in this study were exclusively nurses—and given that other healthcare professionals also play a role in patient safety and the development of their culture—it is also suggested that future studies explore the roles of other healthcare team members in fostering a patient safety culture. Additionally, future research could investigate the impact of patient safety culture on patient care outcomes at the hospital level.

The findings of this study indicate that the implementation of patient safety culture has a significant and positive impact on nurses’ professional behavior. Therefore, if the effectiveness of such interventions is confirmed in future studies, it can be recommended that healthcare personnel, particularly nurses, incorporate these training programs into their professional development initiatives.

One of the key factors related to nurses’ professional behavior is the underreporting of adverse events. This may occur for several reasons, such as the perception that the incident is insignificant, the belief that the event was unavoidable, a lack of awareness regarding unsafe care situations, or fear of leaving a record of an error attributed to the healthcare team. To establish an effective safety culture, it appears essential that incident reporting be based on the timing of patient harm and that preventable events be systematically analyzed and addressed through strategic planning to improve safety conditions.

Another important consideration is nurses’ beliefs about the positive or negative consequences of incident reporting for management and healthcare organizations. In this regard, designing and implementing educational programs on patient safety culture would be highly beneficial for controlling and improving safety-related behaviors and promoting appropriate professional engagement. Such training could ultimately lead to safer care environments and more responsible professional conduct within healthcare settings.

Conclusion

The implementation of patient safety culture has a significant and positive impact on nurses’ professional behavior.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank the Research Deputy of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences for financially supporting this project, as well as all the nurses who participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, with the ethical approval code IR.YUMS.REC.1398.125, issued by the Research Deputy of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology. Data were collected using a demographic information form and the Nursing Students Professional Behaviors Scale (NSPBS). Clinical Trial Code: IRCT20141106019833N3.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Zoladl M (First Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (25%); Mousavi MS (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (15%); Rastian ML (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (25%); Tabatabaei F (Fourth Author), Main Researcher (25%); Salari M (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher (10%)

Funding/Support: This study was financially supported by the Research Deputy of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

Across the globe, healthcare leaders continue to face a complex set of challenges in delivering high-quality care. Patient safety and the quality of care are two of the most pressing concerns in global health systems [1]. Today, medical errors frequently result in patient harm and, in many cases, even death. These errors—such as medication mistakes, delayed referrals, and inadequate follow-up—occur with concerning regularity and directly impact patient safety [2].

Nursing activities are closely tied to patient safety. For example, nurses play key roles in medication administration, infection control, and fall prevention. As such, their efforts to promote patient safety are vital [3]. To implement effective safety strategies, healthcare organizations must adopt a “safety culture” model [4]. One definition of patient safety culture is “an organization’s willingness and ability to understand safety (and its risks), as well as its willingness and ability to act toward safety” [5].

Patient safety culture reflects the level of commitment, leadership style, and competency within healthcare institutions. The development of this culture can be influenced by the professional behavior of healthcare staff—behavior that is itself shaped by organizational management [6]. Professional behavior is a fundamental concept in nursing, referring to adherence to specific behavioral standards that improve care performance. It is essential for the effective execution of nursing duties and is directly linked to both performance outcomes and patient results [7]. Education in patient safety culture plays an important role in medical sciences by promoting proactive engagement in identifying and addressing patient safety issues [8].

Agbar et al. state that patient safety programs can positively influence and improve the culture of safety among healthcare personnel [9]. Similarly, Rahimi et al. found that patient safety culture should be integrated into quality and safety improvement initiatives in patient care. They emphasize the need for non-punitive safety policies, staff support, and effective educational programs in hospitals [10].

Despite the recognized importance of patient safety culture, few studies have directly and purposefully investigated its impact on the professional behavior of nurses in clinical settings. Most existing research has been descriptive and has not employed randomized controlled designs. This highlights a clear need for further investigation into the effects of safety culture on the professional behavior of nurses. The lack of definitive and reliable evidence in this area has created a gap in the literature. The present study aimed to address this gap and provide scientific evidence on the subject. Therefore, this research was conducted to determine the effect of patient safety culture on nurses’ professional behavior.

Materials and Methods

This interventional, controlled field trial was conducted in 2021 on 84 nurses working in hospitals affiliated with Yasuj University of Medical Sciences. Participants were selected through convenience sampling and were randomly assigned using block randomization into two equal groups, including the intervention (n=42) and control (n=42) groups.

The sample size was calculated using G*Power software version 3.1.9.7, considering a type I error (alpha) of 0.01, a confidence level of 99%, a type II error (beta) of 0.10, and a test power of 90%. Based on these parameters, the required number of participants in each group was calculated to be 34.63. Accounting for a 20% potential dropout rate, the final sample size was determined to be 42 participants per group, totaling 84 participants.

Inclusion criteria included having a bachelor’s or master’s degree in nursing, the ability to communicate and respond to questions, willingness to participate in the study, and active employment in a teaching hospital. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to continue participation, prior involvement in similar studies within the last six months, and obtaining a score of 64 or higher on the Nursing Students Professional Behaviors Scale (NSPBS).

Data were collected using a demographic information form and the NSPBS.

The NSPBS was developed by Goz and Geckil in 2010 to assess the professional behaviors of nursing students. It contains 27 items covering three dimensions, namely health care practices (items 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 16-21, 23, 25-27), activity practices (items 2, 5, 7, 11, 13-15), and reporting (items 22, 24). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). The total score ranges from 27 to 135, with higher scores indicating higher levels of professional nursing behavior [11]. The scale’s validity was confirmed by Heshmati Nabavi et al. in 2014, reporting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 for the overall scale [12]. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.69 to 0.80 across the subscales and was 0.71 for the total scale.

Data collection involved in-person interviews, during which participants were screened according to the inclusion criteria and signed informed consent forms. They were then provided with the demographic form and the NSPBS. The intervention was conducted in a designated room within one of the hospital wards affiliated with Yasuj University of Medical Sciences. Prior to the intervention, participants in the intervention group were briefed about group rules and responsibilities. The intervention sessions, conducted by the researcher in a group format, consisted of four 120-minute sessions over the course of one month. The control group did not receive any educational intervention. One month after the completion of the intervention, the professional behavior of the nurses was reassessed using the NSPBS.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 21, applying Chi-square tests, independent t-tests, and paired t-tests. A significance level of 0.01 was considered for all tests.

Findings

A total of 84 nurses participated in this study, and all remained until the end of the study. The mean age of the participants was 31.40±4.60 years. The mean age was 31.4±3.8 years in the intervention group and 31.4±5.4 years in the control group (p=0.89), while the mean work experience was 6.3±7.7 years in the intervention group and 6.3±6.5 years in the control group (p=0.93; Table 1)

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants

There was no statistically significant difference in mean overall professional behavior scores of the nurses and their subscales between the two groups before the intervention (p>0.05), indicating baseline similarity between the intervention and control groups. However, the between-group comparison after the intervention revealed a statistically significant difference in the mean scores of the overall professional behavior of the nurses and their subscales (p<0.0001).

Additionally, intra-group comparisons were conducted to examine changes within each group separately. There was a statistically significant improvement in the intervention group before and after the intervention (p<0.0001), while no significant change was observed in the control group (p>0.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the mean overall nurses' professional behavior scores and their subscales in both groups

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effect of patient safety culture on nurses’ professional behavior. One month after the intervention, the mean score of professional behavior of nurses in the intervention group increased significantly compared to the control group. Implementing a patient safety culture had a positive impact on enhancing the professional behavior of nurses, which aligns with the results of studies by Berry et al. [13], Sortedahl et al. [14], and Dyrbye et al. [15].

Similarly, Ayu Eka et al. emphasize the necessity for nurse educators to model professional behavior and actively promote a culture of professional nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure full presence and comprehensive care delivery [16], which is consistent with the present study. Furthermore, Lee and Kwon found that ensuring patient safety through the creation of safe work environments and fostering an organizational culture that prioritizes patient safety are essential steps to encourage nurses to raise concerns and openly discuss safety-related issues, including their own behaviors [17]. These findings also support the current study.

Measuring patient safety culture provides an opportunity to identify shared areas for quality improvement, reducing the likelihood of adverse events, and enhancing the overall quality of care. Moreover, quality improvement strategies are aligned with the promotion of patient safety culture within hospitals. Therefore, educational programs for healthcare professionals should incorporate more content related to patient safety, particularly emphasizing communication, leadership, non-punitive error reporting, quality improvement, and teamwork [18].

Based on our findings, it can be concluded that implementing a patient safety culture is both essential and impactful in promoting the professional behavior of nurses. Notably, this study also observed improvements in communication skills and teamwork capabilities among nurses following the intervention. In line with this, Yayeh et al. reported that caring behaviors among nurses are influenced by factors, such as professional satisfaction, job satisfaction, low workload, and good relationships with colleagues, all of which contribute to improved quality of nursing care [19]. Additionally, Masibo et al. found that professional performance in nursing is not gender-dependent and that nurses’ perceptions of their profession, institutional factors, and opportunities for professional development significantly impact their performance [20].

Among the strengths of this study are the selection of two critical factors (patient safety and professional behavior), both of which are vital to improving the quality of nursing services. Furthermore, the integration of safety and professional behavior concepts, which are often studied separately, adds value and novelty to this research.

However, the study also had limitations. One limitation was the use of self-report questionnaires to assess professional behaviors without incorporating complementary tools such as direct observation or performance evaluations. Another limitation was the possibility that the self-reported data might not fully reflect participants’ actual behaviors. Moreover, the study did not simultaneously assess other potential psychological or environmental factors that may influence professional behavior.

Given these findings, and considering that this study was conducted solely in teaching hospitals in Yasuj, it is recommended that similar research be carried out in other hospitals across the country. Since the participants in this study were exclusively nurses—and given that other healthcare professionals also play a role in patient safety and the development of their culture—it is also suggested that future studies explore the roles of other healthcare team members in fostering a patient safety culture. Additionally, future research could investigate the impact of patient safety culture on patient care outcomes at the hospital level.

The findings of this study indicate that the implementation of patient safety culture has a significant and positive impact on nurses’ professional behavior. Therefore, if the effectiveness of such interventions is confirmed in future studies, it can be recommended that healthcare personnel, particularly nurses, incorporate these training programs into their professional development initiatives.

One of the key factors related to nurses’ professional behavior is the underreporting of adverse events. This may occur for several reasons, such as the perception that the incident is insignificant, the belief that the event was unavoidable, a lack of awareness regarding unsafe care situations, or fear of leaving a record of an error attributed to the healthcare team. To establish an effective safety culture, it appears essential that incident reporting be based on the timing of patient harm and that preventable events be systematically analyzed and addressed through strategic planning to improve safety conditions.

Another important consideration is nurses’ beliefs about the positive or negative consequences of incident reporting for management and healthcare organizations. In this regard, designing and implementing educational programs on patient safety culture would be highly beneficial for controlling and improving safety-related behaviors and promoting appropriate professional engagement. Such training could ultimately lead to safer care environments and more responsible professional conduct within healthcare settings.

Conclusion

The implementation of patient safety culture has a significant and positive impact on nurses’ professional behavior.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank the Research Deputy of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences for financially supporting this project, as well as all the nurses who participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, with the ethical approval code IR.YUMS.REC.1398.125, issued by the Research Deputy of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology. Data were collected using a demographic information form and the Nursing Students Professional Behaviors Scale (NSPBS). Clinical Trial Code: IRCT20141106019833N3.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Zoladl M (First Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (25%); Mousavi MS (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (15%); Rastian ML (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (25%); Tabatabaei F (Fourth Author), Main Researcher (25%); Salari M (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher (10%)

Funding/Support: This study was financially supported by the Research Deputy of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

References

1. Ahmed Z, Ellahham S, Soomro M, Shams S, Latif K. Exploring the impact of compassion and leadership on patient safety and quality in healthcare systems: A narrative review. BMJ Open Qual. 2024;13(Suppl 2):e002651. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjoq-2023-002651]

2. Kalantari H, Raeissi P, Aryankhesal A, Hashemi SM, Reisi N. Patient safety domains in primary healthcare: A systematic review. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2024;34(1):73-84. [Link] [DOI:10.4314/ejhs.v34i1.9]

3. Huh A, Shin JH. Person-centered care practice, patient safety competence, and patient safety nursing activities of nurses working in geriatric hospitals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5169. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18105169]

4. Rocha RC, Abreu IMd, Carvalho REFLd, Rocha SSd, Madeira MZdA, Avelino FVSD, et al. Patient safety culture in surgical centers: Nursing perspectives. REVISTA DA ESCOLA DE ENFERMAGEM DA USP. 2021;55:e03774. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/s1980-220x2020034003774]

5. Venesoja A, Lindström V, Castrén M, Tella S. Prehospital nursing students' experiences of patient safety culture in emergency medical services-A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(5-6):847-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jocn.16396]

6. Campelo CL, Nunes FDO, Silva LDC, Guimarães LF, Sousa SMA, Paiva SS. Patient safety culture among nursing professionals in the intensive care environment. REVISTA DA ESCOLA DE ENFERMAGEM DA USP. 2021;55:e03754. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/s1980-220x2020016403754]

7. Zahedpasha B, Sahebalzamani M, Fattah Moghaddam L. The relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and professional behavior mediated by nurses' physical health. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2021;23(1):405-11. [Persian] [Link]

8. Ezzi O, Mahjoub M, Omri N, Ammar A, Loghmari D, Chelly S, et al. Patient safety in medical education: Tunisian students' attitudes. Libyan J Med. 2022;17(1):2122159. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/19932820.2022.2122159]

9. Agbar F, Zhang S, Wu Y, Mustafa M. Effect of patient safety education interventions on patient safety culture of health care professionals: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;67:103565. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103565]

10. Rahimi E, Alizadeh S, Safaeian A, Abbasgholizadeh N. An investigation of patient safety culture: The beginning for quality and safety improvement plans in patient care services. J Health. 2020;11(2):235-47. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/j.health.11.2.235]

11. Goz F, Geckil E. Nursing students professional behaviors scale (NSPBS) validity and reliability. Pak J Med Sci. 2010;26(4):938-41. [Link]

12. Heshmati Nabavi F, Rajabpour M, Hoseinpour Z, Hemmati Maslakpak M, Hajiabadi F, Mazlom R, et al. Comparison of nursing students' professional behavior to nurses employed in Mashhad university of medical sciences. Iran J Med Educ. 2014;13(10):809-19. [Persian] [Link]

13. Berry JC, Davis JT, Bartman T, Hafer CC, Lieb LM, Khan N, et al. Improved safety culture and teamwork climate are associated with decreases in patient harm and hospital mortality across a hospital system. J Patient Saf. 2020;16(2):130-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000251]

14. Sortedahl C, Ellefson S, Fotsch D, Daley K. The professional behaviors new nurses need: Findings from a national survey of hospital nurse leaders. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2020;41(4):207-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000622]

15. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Leep Hunderfund A, Johnson P, Cipriano P, Peterson C, et al. Relationship between burnout and professional behaviors and beliefs among US nurses. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(11):959-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002014]

16. Ayu Eka NG, Rumerung CL, Tahulending PS. Role modeling of professional behavior in nursing education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed method study. J Holist Nurs. 2024;42(2 Suppl):S47-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/08980101231179300]

17. Lee E, Kwon H. Cluster of speaking-up behavior in clinical nurses and its association with nursing organizational culture, teamwork, and working condition: A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag. 2024;2024:9109428. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/jonm/9109428]

18. Camacho-Rodríguez DE, Carrasquilla-Baza DA, Dominguez-Cancino KA, Palmieri PA. Patient safety culture in Latin American hospitals: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):14380. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph192114380]

19. Yayeh MB, Dinkayehu TE, Endrias EE, Assegie MT. Prevalence and associated factors of caring behavior among nurses in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2025;25(1):756. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-025-12916-1]

20. Masibo RM, Kibusi SM, Masika GM. Gender dynamics in nursing profession: Impact on professional practice and development in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):1179. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-024-11641-5]