Volume 6, Issue 3 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(3): 155-160 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.YUMS.REC.1401.165

History

Received: 2025/06/1 | Accepted: 2025/07/5 | Published: 2025/07/9

Received: 2025/06/1 | Accepted: 2025/07/5 | Published: 2025/07/9

How to cite this article

Ghodsi N, Manzouri L, Mousavizade A, Moradi-Joo M. Health Literacy in Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening in the Southwest of Iran. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (3) :155-160

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-433-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-433-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Student Research Committee, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (170 Views)

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common known malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide [1]. It has long been a concern for health authorities due to its increasing prevalence, which affects women and undermines family foundations. The relatively long pre-clinical period, which allows for early detection, combined with a high survival rate when detected early, makes breast cancer a suitable candidate for screening. The American Cancer Society recommends breast self-examinations starting in the second decade of life, examinations by a doctor at least every three years during the second and third decades of life, and annual mammography for asymptomatic women aged 40 years and older to facilitate early detection of breast cancer in individuals at average risk for the disease [2].

Although most types of breast cancer have a relatively good prognosis, it remains one of the deadliest cancers in women, necessitating early diagnosis to prevent mortality. Mammography is one of the key methods for early detection, and it is essential to inform eligible women about the benefits and risks of screening methods, including mammography. Studies indicate that women in European countries often lack sufficient knowledge about the benefits and harms of screening methods, which is linked to the issue of health literacy. Health literacy encompasses the knowledge, motivation, and access necessary to understand, evaluate, and utilize health information to make informed decisions about health, prevent diseases, and enhance overall well-being, thereby improving quality of life [3].

Cervical cancer is the third most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. According to estimates from 2008, cervical cancer accounts for 9% of new cancer cases and 8% of cancer deaths in women. It is estimated that 95% of women in developing countries have never been screened for cervical cancer. In Iran, although this cancer is not among the 10 most common cancers, it is of considerable importance because it can be prevented by vaccination and identified through timely screening in the early stages [2]. Cervical cancer primarily affects individuals aged 35-44 years and is less common in those under 20 years of age. The overall 5-year survival rate is 66%, with rates of 71% in white women and 58% in black women [4].

Population-based screening programs are recognized as effective methods for detecting breast and cervical cancer. Studies show that screening every two years reduces the rate of breast cancer by 26%, while Pap smear screening decreases the rate of cervical cancer by 80%. The effectiveness of screening programs depends on various factors. Among these factors are the socio-economic, cultural, and psychological levels of the patients, which vary among individuals and can contribute to the higher mortality rates caused by these cancers in those lacking these factors. The level of health literacy can be considered a predictive factor for individuals’ health status and influences their ability to make informed health decisions, prevent diseases, and improve their health. A low level of health literacy is associated with increased hospitalization, and there is a relationship between higher medication consumption and decreased use of disease prevention methods, including cancer screening [5].

In the health system, to prevent and control diseases, the transmission of information presented in simple language and based on appropriate content plays a significant role alongside the provision of health services. These factors have led to the emergence of a new concept called health literacy [6]. Health literacy is defined as a person’s capacity to acquire, interpret, and understand basic information and health services necessary for making appropriate decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention, and health promotion to maintain or improve their quality of life [7].

According to studies by the Center for Health Care Strategies in the United States, people with low health literacy are less likely to understand the written and spoken information provided by health professionals and to follow the given instructions. They also incur higher medical costs, experience poorer health, and have higher rates of hospitalization and use of emergency services, while utilizing less preventive care, including cancer screening programs [7].

In a study in the United States, health literacy has the strongest association with adherence to mammography screening among sociodemographic factors, such as ethnicity, language, education, smoking status, insurance, income, employment, and family history of breast cancer. Additionally, low health literacy is found to have a negative association with up-to-date adherence to breast cancer screening programs. On the other hand, the World Health Organization advocates that the first step toward effective strategies for promoting early diagnosis in communities is improving health literacy [7].

The study by Elobaid et al. showed that 45% of women do not have sufficient information about clinical breast exams and mammography [8]. In a study conducted with women aged 14–84 years in the Northeast of Iran, 84% of women also lack sufficient information about breast cancer and screening methods [9]. Baccolini et al. reveal a significant association between an adequate level of health literacy and higher participation in screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers [5]. In the study by Danaei et al., the education level of a spouse is identified as a predictive factor for health literacy in women with breast cancer. The odds of having sufficient health literacy are 4.33 times higher for spouses with a high school diploma and 5.87 times higher for spouses with a university degree compared to participants whose spouses have an education level lower than a diploma [10].

The results of a study in Turkey involving women of reproductive age indicated that the majority has a low level of health literacy and also lacks sufficient information about breast cancer prevention [11]. In the study by Rajabi et al., improvements in health literacy following educational interventions lead to enhanced breast self-examination, increased use of clinical breast examinations, and higher rates of mammography [12]. Ramaswamy et al. reveal that improvements in cervical health literacy following an intervention are associated with increased self-efficacy for cervical cancer screening and follow-up [13]. Emerson et al. note that improvements in health literacy after an intervention lead to an increase in up-to-date Pap screenings compared to pre-intervention levels [14].

Due to the importance of this issue and the limited evidence regarding health literacy related to cancer screening in the Southwest of Iran, this study investigated health literacy concerning breast and cervical cancer screening in that region.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 294 women aged 20–69 years selected using a computer-based simple random sampling from four urban health centers in Yasuj City during 2022–2023. There are four urban health centers in Yasuj City. After calculating the total sample size based on the frequency of women at each center, the sample was distributed proportionally. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The sample size was calculated based on the study by Ghanbari et al. [15], considering p = 57% (favorable health literacy), α = 0.05, and d = 0.1. The formula used was n=(Z1-α/2)2 P (1-P)/d2. Inclusion criteria included women aged 20–69 years, the ability to read and write, and consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criterion included incomplete completion of the checklist and questionnaire.

Data collection was conducted using a demographic checklist (which included age, education, marital status, and occupational status) and the Assessment of Health Literacy in Cancer Screening (AHL-C). The AHL-C, developed and validated by Hae-Ra Ham et al., consists of 52 questions across four domains: 1) print literacy (24 questions, score range 0–24), 2) numeracy (12 questions, score range 0–12), 3) comprehension (12 questions, score range 0–12), and 4) familiarity (12 questions, score range 0–12). Cross-cultural adaptation, as well as validity and reliability testing of the Persian version of the Health Literacy Questionnaire, was completed.

The reach procedure included four stage. In the first stage (forward translation), the original English version of the questionnaire was translated into Persian by two official translators. In the second stage (incorporation), a meeting was held with the researchers present to review the two translated versions of the questionnaire. Finally, through agreement, an initial joint translation was obtained. In the third stage (backward translation), the joint Persian translation prepared in the previous stage was translated back into English by two native speakers who are fluent in both Persian and English. Finally, in the fourth stage (comparison), the two English translations obtained in the previous stage were compared by the research team with the original version of the questionnaire in terms of meaning, resulting in the final Persian questionnaire. The content validity index was 0.97, the content validity ratio was 0.9, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87. In the confirmatory factor analysis, the minimum discrepancy function divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) was 2.24, incremental fit index (IFI) was 0.732, comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.728, the HOLTER index was 0.01, and Tucker–Lewis INDEX (TLI) was 0.7, confirming the standardization of the questionnaire. For the assessment of health literacy, the existing grading from the health literacy survey conducted in eight European countries in 2011 was utilized. Two-thirds and five-sixths of the total possible points were considered as separate thresholds for health literacy levels. Given that the maximum score is 52, a score of 0–35 was classified as unfavorable health literacy, a score of 36–43 as borderline health literacy, and a score of 44–52 as favorable health literacy [16].

The data were analyzed using SPSS 25 software. The normal distribution of quantitative data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis, and ordinal logistic regression were utilized for data analysis, with a significance level set at 0.05.

Findings

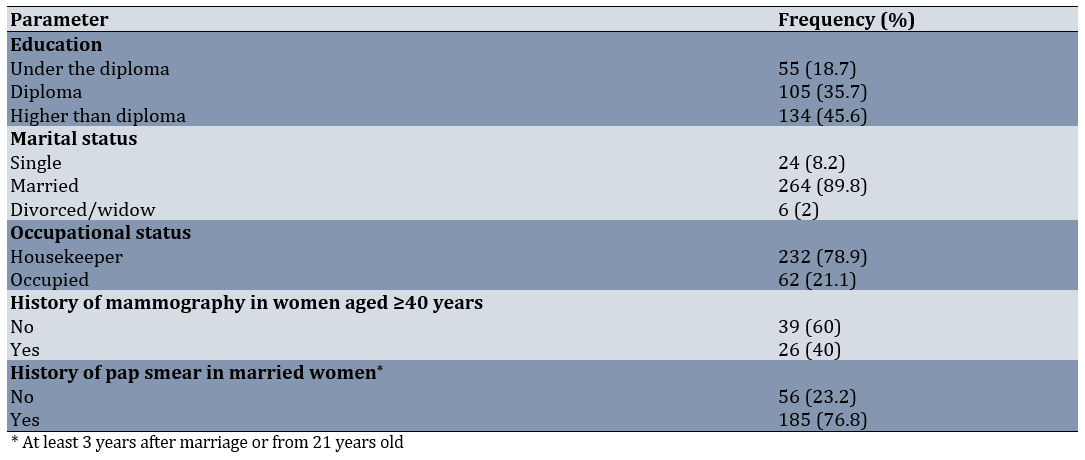

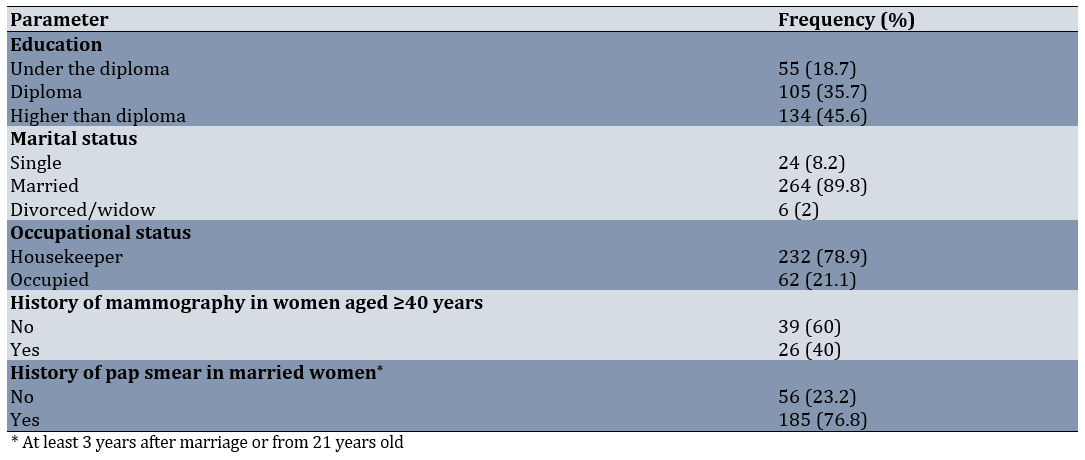

A total of 294 women aged 20-69 years enrolled in the study. The mean age of participants was 33.00±7.88 years (range: 20-56; Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

The mean age for the first mammography and Pap smear was 36.11±7.29 and 26.77±5.73, respectively. The mean score of health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening was 42.55±5.43. The distribution of health literacy levels was as follows: 33 participants (11.2%) were categorized as having unfavorable health literacy, 116 participants (39.5%) were classified as having intermediate health literacy, and 145 participants (49.3%) were identified as having favorable health literacy.

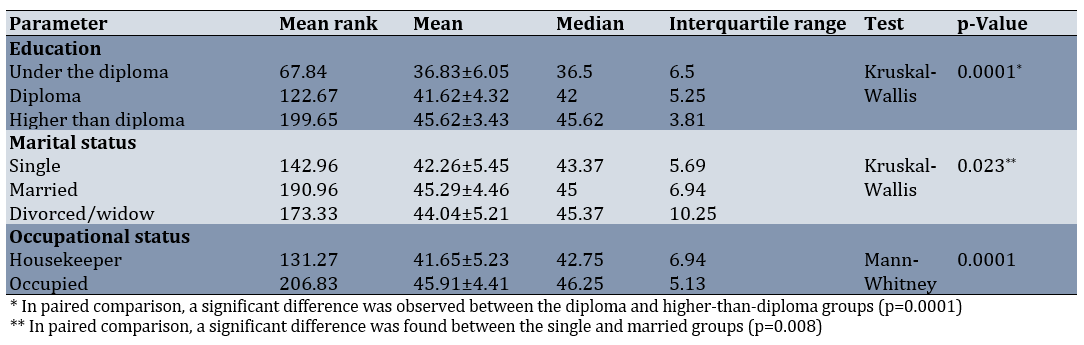

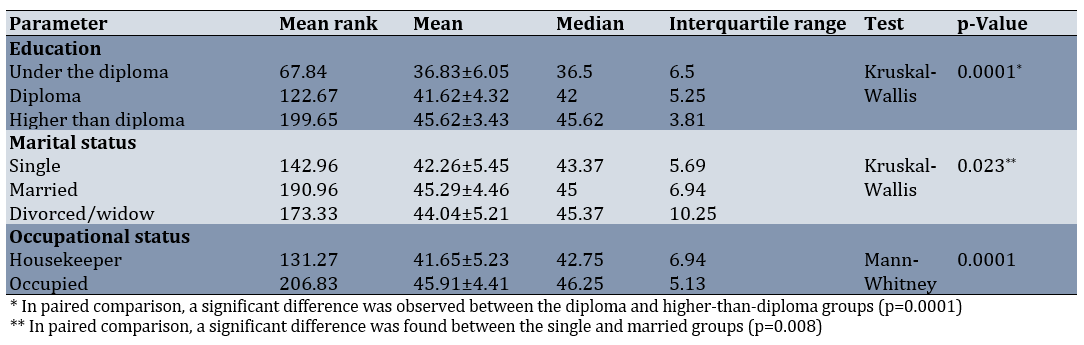

There was no significant correlation between age and health literacy score (p=0.78, r=0.016). According to the Chi-Square test, there was no significant relationship between the level of health literacy and the history of undergoing mammography (p=0.75, r=0.58, df=2) or Pap smear (p=0.5, r=1.23, df=2; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening based on the demographic characteristics

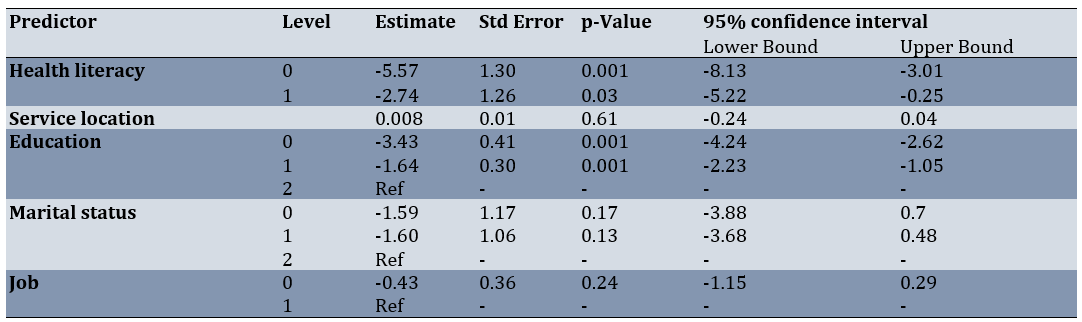

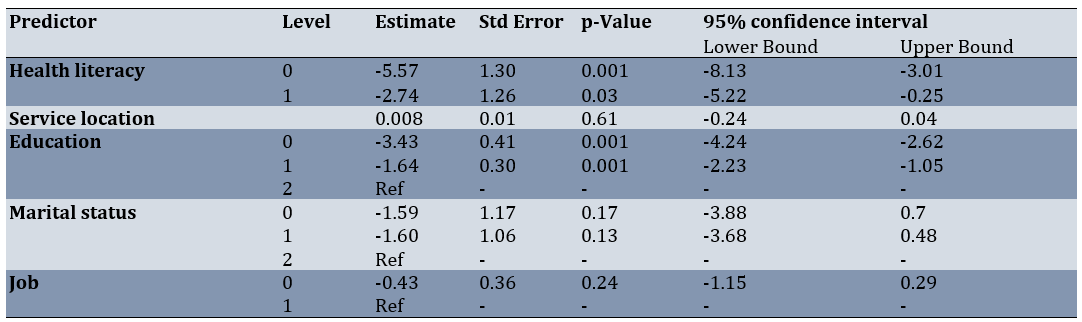

Predictive factors of health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening were found using ordinal logistic regression (Table 3).

Table 3. Predicting factors of health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening based on the ordinal logistic regression

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening and its associated factors. Nearly 50%, 39%, and 11% of participants had favorable, intermediate, and unfavorable health literacy, respectively. Rakhshani et al. indicated that 83%, 14%, and 3% of subjects have sufficient, borderline, and inadequate health literacy, respectively [17]. In the study by Rakhshkhorshid et al., 89.6% and 10.4% of participants have limited and marginal health literacy, respectively, and no participants has adequate health literacy [18]. In another study conducted by Batooli and Mohamadloo, health literacy is moderate in half of the participants [19]. Another study revealed that half of the women have a low level of health literacy [20]. Poon et al. found that over two-thirds of participants have problematic or inadequate health literacy [7]. Danaei et al. showed that 15.3% of women have inadequate health literacy [10]. Except for the study by Rakhshani et al. [17], our results are approximately in line with the others. The differences in the results of these studies could be multifactorial, including the use of different tools to measure health literacy, cultural differences, and variations in access to healthcare or socioeconomic status.

The related determinants of health literacy identified in the univariate analysis were marital status, education level, and employment status. Women with higher education, those who were married or ever married, and those who were employed exhibited higher health literacy. In the multivariate analysis, education level was the only predicting factor for health literacy. Previous studies have shown that a higher educational level is significantly associated with greater cancer screening health literacy [10, 13, 17–20]. In other studies, employment [10, 17, 18] and marital status [10, 21] are also significantly associated with higher health literacy scores, which supports our findings. Given that education level was the strongest predictor of health literacy, it is essential to consider the necessity of developing simplified written, audio, or video educational materials tailored to an appropriate reading level to improve women’s health literacy. This is important because low health literacy may also influence the source and accuracy of the information received.

Aslo, 60% of women had never undergone mammography. According to national breast cancer control and screening guidelines, women are recommended to begin screening mammography at age 40 [18]. Participation in regular breast cancer screening is advised as the best method to detect potential cancerous growths at the earliest stage, thereby reducing cancer progression and mortality [22]. The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) has set a goal to achieve at least 70% adherence to mammography screening. In the study by Loewen et al., 79.3% of participants report timely screening, and only 5.5% had never been screened [22]. Other researchers have reported that 70% [12] and 88% [17] of women had never undergone screening mammography. Rakhshkhorshid et al. note that none of their participants perform a mammographic screening [18]. Therefore, the causes of low participation in screening mammography are an important issue that should be addressed by healthcare providers and policymakers. Some probable causes for not undergoing screening mammography include a lack of knowledge about mammography, unawareness of service locations, fear of radiation, fear of pain, fear of positive results, inconvenient service times, and lack of time [7].

Nearly 70% of the women reported having undergone a Pap smear. Ramaswamy et al. [13] and Rakhshani et al. [17] report that 67% and 53% of their participants undergo a Pap smear, respectively. Although the percentage of women performing Pap smears is higher in our study, further investigation focusing on the barriers to attending Pap smear screenings is necessary.

No association was found between health literacy and undergoing mammography or Pap smears. The results of Goto et al. align with our findings [23]. In the study by Rakhshani et al. [17], there is a significant correlation between health literacy and performing Pap smears; however, no correlation is found between health literacy and undergoing mammography. Given that some studies [5, 7, 24] have reported a significant correlation between health literacy and performing both mammograms and Pap smears, further investigation is needed that focuses on the barriers and reasons for non-adherence to these screenings. Additionally, the impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, which has led to a reduction in participation rates across all types of cancer screening programs—even after its control—must be acknowledged.

There was no association between age and health literacy, which aligns with the findings of Rakhshani et al. [17]. In the studies by Haghighi et al. [25] and Cudjoe et al. [26], a significant reverse correlation is shown between age and health literacy. A possible explanation for this could be that poor literacy associated with increasing age may result from reduced cognitive function and sensory abilities [19]. In contrast, the studies by Barati et al. [27] and Sun et al. [20] found that older age is significantly associated with higher cancer screening health literacy. Given the discrepancies in the results of these studies, further research is warranted to systematically investigate how age influences cancer screening health literacy among women.

The researcher found few studies that investigated the health literacy of breast and cervical cancer together. Therefore, we compared our results with existing similar studies related to health literacy in breast and cervical cancer screening. Additionally, since this study was cross-sectional, causality cannot be assumed when addressing the relationship between cancer screening health literacy and demographic characteristics.

Given that half of the participants did not have adequate health literacy and that education level was the strongest predictor of health literacy, health policymakers and healthcare providers should consider interventions based on demographic characteristics. This may include revising and simplifying teaching materials, as well as incorporating oral, pictorial, and written materials in the form of posters and pamphlets to enhance health literacy skills in the community. Additionally, promoting the communication skills of healthcare providers should also be taken into account.

Conclusion

Half of the participants do not have adequate health literacy and education level is the strongest predictor of health literacy.

Acknowledgments: We would like to sincerely thank the family health unit of the provincial health center, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran.

Ethical Permissions: The present study was ethically approved by the Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research (IR.YUMS.REC.1401.165).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution: Ghodsi N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Manzouri L (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (50%); Mousavizadeh A (Third Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Moradi-Joo M (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (10%)

Funding/Support: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Breast cancer is the most common known malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide [1]. It has long been a concern for health authorities due to its increasing prevalence, which affects women and undermines family foundations. The relatively long pre-clinical period, which allows for early detection, combined with a high survival rate when detected early, makes breast cancer a suitable candidate for screening. The American Cancer Society recommends breast self-examinations starting in the second decade of life, examinations by a doctor at least every three years during the second and third decades of life, and annual mammography for asymptomatic women aged 40 years and older to facilitate early detection of breast cancer in individuals at average risk for the disease [2].

Although most types of breast cancer have a relatively good prognosis, it remains one of the deadliest cancers in women, necessitating early diagnosis to prevent mortality. Mammography is one of the key methods for early detection, and it is essential to inform eligible women about the benefits and risks of screening methods, including mammography. Studies indicate that women in European countries often lack sufficient knowledge about the benefits and harms of screening methods, which is linked to the issue of health literacy. Health literacy encompasses the knowledge, motivation, and access necessary to understand, evaluate, and utilize health information to make informed decisions about health, prevent diseases, and enhance overall well-being, thereby improving quality of life [3].

Cervical cancer is the third most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. According to estimates from 2008, cervical cancer accounts for 9% of new cancer cases and 8% of cancer deaths in women. It is estimated that 95% of women in developing countries have never been screened for cervical cancer. In Iran, although this cancer is not among the 10 most common cancers, it is of considerable importance because it can be prevented by vaccination and identified through timely screening in the early stages [2]. Cervical cancer primarily affects individuals aged 35-44 years and is less common in those under 20 years of age. The overall 5-year survival rate is 66%, with rates of 71% in white women and 58% in black women [4].

Population-based screening programs are recognized as effective methods for detecting breast and cervical cancer. Studies show that screening every two years reduces the rate of breast cancer by 26%, while Pap smear screening decreases the rate of cervical cancer by 80%. The effectiveness of screening programs depends on various factors. Among these factors are the socio-economic, cultural, and psychological levels of the patients, which vary among individuals and can contribute to the higher mortality rates caused by these cancers in those lacking these factors. The level of health literacy can be considered a predictive factor for individuals’ health status and influences their ability to make informed health decisions, prevent diseases, and improve their health. A low level of health literacy is associated with increased hospitalization, and there is a relationship between higher medication consumption and decreased use of disease prevention methods, including cancer screening [5].

In the health system, to prevent and control diseases, the transmission of information presented in simple language and based on appropriate content plays a significant role alongside the provision of health services. These factors have led to the emergence of a new concept called health literacy [6]. Health literacy is defined as a person’s capacity to acquire, interpret, and understand basic information and health services necessary for making appropriate decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention, and health promotion to maintain or improve their quality of life [7].

According to studies by the Center for Health Care Strategies in the United States, people with low health literacy are less likely to understand the written and spoken information provided by health professionals and to follow the given instructions. They also incur higher medical costs, experience poorer health, and have higher rates of hospitalization and use of emergency services, while utilizing less preventive care, including cancer screening programs [7].

In a study in the United States, health literacy has the strongest association with adherence to mammography screening among sociodemographic factors, such as ethnicity, language, education, smoking status, insurance, income, employment, and family history of breast cancer. Additionally, low health literacy is found to have a negative association with up-to-date adherence to breast cancer screening programs. On the other hand, the World Health Organization advocates that the first step toward effective strategies for promoting early diagnosis in communities is improving health literacy [7].

The study by Elobaid et al. showed that 45% of women do not have sufficient information about clinical breast exams and mammography [8]. In a study conducted with women aged 14–84 years in the Northeast of Iran, 84% of women also lack sufficient information about breast cancer and screening methods [9]. Baccolini et al. reveal a significant association between an adequate level of health literacy and higher participation in screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers [5]. In the study by Danaei et al., the education level of a spouse is identified as a predictive factor for health literacy in women with breast cancer. The odds of having sufficient health literacy are 4.33 times higher for spouses with a high school diploma and 5.87 times higher for spouses with a university degree compared to participants whose spouses have an education level lower than a diploma [10].

The results of a study in Turkey involving women of reproductive age indicated that the majority has a low level of health literacy and also lacks sufficient information about breast cancer prevention [11]. In the study by Rajabi et al., improvements in health literacy following educational interventions lead to enhanced breast self-examination, increased use of clinical breast examinations, and higher rates of mammography [12]. Ramaswamy et al. reveal that improvements in cervical health literacy following an intervention are associated with increased self-efficacy for cervical cancer screening and follow-up [13]. Emerson et al. note that improvements in health literacy after an intervention lead to an increase in up-to-date Pap screenings compared to pre-intervention levels [14].

Due to the importance of this issue and the limited evidence regarding health literacy related to cancer screening in the Southwest of Iran, this study investigated health literacy concerning breast and cervical cancer screening in that region.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 294 women aged 20–69 years selected using a computer-based simple random sampling from four urban health centers in Yasuj City during 2022–2023. There are four urban health centers in Yasuj City. After calculating the total sample size based on the frequency of women at each center, the sample was distributed proportionally. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The sample size was calculated based on the study by Ghanbari et al. [15], considering p = 57% (favorable health literacy), α = 0.05, and d = 0.1. The formula used was n=(Z1-α/2)2 P (1-P)/d2. Inclusion criteria included women aged 20–69 years, the ability to read and write, and consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criterion included incomplete completion of the checklist and questionnaire.

Data collection was conducted using a demographic checklist (which included age, education, marital status, and occupational status) and the Assessment of Health Literacy in Cancer Screening (AHL-C). The AHL-C, developed and validated by Hae-Ra Ham et al., consists of 52 questions across four domains: 1) print literacy (24 questions, score range 0–24), 2) numeracy (12 questions, score range 0–12), 3) comprehension (12 questions, score range 0–12), and 4) familiarity (12 questions, score range 0–12). Cross-cultural adaptation, as well as validity and reliability testing of the Persian version of the Health Literacy Questionnaire, was completed.

The reach procedure included four stage. In the first stage (forward translation), the original English version of the questionnaire was translated into Persian by two official translators. In the second stage (incorporation), a meeting was held with the researchers present to review the two translated versions of the questionnaire. Finally, through agreement, an initial joint translation was obtained. In the third stage (backward translation), the joint Persian translation prepared in the previous stage was translated back into English by two native speakers who are fluent in both Persian and English. Finally, in the fourth stage (comparison), the two English translations obtained in the previous stage were compared by the research team with the original version of the questionnaire in terms of meaning, resulting in the final Persian questionnaire. The content validity index was 0.97, the content validity ratio was 0.9, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87. In the confirmatory factor analysis, the minimum discrepancy function divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) was 2.24, incremental fit index (IFI) was 0.732, comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.728, the HOLTER index was 0.01, and Tucker–Lewis INDEX (TLI) was 0.7, confirming the standardization of the questionnaire. For the assessment of health literacy, the existing grading from the health literacy survey conducted in eight European countries in 2011 was utilized. Two-thirds and five-sixths of the total possible points were considered as separate thresholds for health literacy levels. Given that the maximum score is 52, a score of 0–35 was classified as unfavorable health literacy, a score of 36–43 as borderline health literacy, and a score of 44–52 as favorable health literacy [16].

The data were analyzed using SPSS 25 software. The normal distribution of quantitative data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis, and ordinal logistic regression were utilized for data analysis, with a significance level set at 0.05.

Findings

A total of 294 women aged 20-69 years enrolled in the study. The mean age of participants was 33.00±7.88 years (range: 20-56; Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

The mean age for the first mammography and Pap smear was 36.11±7.29 and 26.77±5.73, respectively. The mean score of health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening was 42.55±5.43. The distribution of health literacy levels was as follows: 33 participants (11.2%) were categorized as having unfavorable health literacy, 116 participants (39.5%) were classified as having intermediate health literacy, and 145 participants (49.3%) were identified as having favorable health literacy.

There was no significant correlation between age and health literacy score (p=0.78, r=0.016). According to the Chi-Square test, there was no significant relationship between the level of health literacy and the history of undergoing mammography (p=0.75, r=0.58, df=2) or Pap smear (p=0.5, r=1.23, df=2; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening based on the demographic characteristics

Predictive factors of health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening were found using ordinal logistic regression (Table 3).

Table 3. Predicting factors of health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening based on the ordinal logistic regression

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate health literacy related to breast and cervical cancer screening and its associated factors. Nearly 50%, 39%, and 11% of participants had favorable, intermediate, and unfavorable health literacy, respectively. Rakhshani et al. indicated that 83%, 14%, and 3% of subjects have sufficient, borderline, and inadequate health literacy, respectively [17]. In the study by Rakhshkhorshid et al., 89.6% and 10.4% of participants have limited and marginal health literacy, respectively, and no participants has adequate health literacy [18]. In another study conducted by Batooli and Mohamadloo, health literacy is moderate in half of the participants [19]. Another study revealed that half of the women have a low level of health literacy [20]. Poon et al. found that over two-thirds of participants have problematic or inadequate health literacy [7]. Danaei et al. showed that 15.3% of women have inadequate health literacy [10]. Except for the study by Rakhshani et al. [17], our results are approximately in line with the others. The differences in the results of these studies could be multifactorial, including the use of different tools to measure health literacy, cultural differences, and variations in access to healthcare or socioeconomic status.

The related determinants of health literacy identified in the univariate analysis were marital status, education level, and employment status. Women with higher education, those who were married or ever married, and those who were employed exhibited higher health literacy. In the multivariate analysis, education level was the only predicting factor for health literacy. Previous studies have shown that a higher educational level is significantly associated with greater cancer screening health literacy [10, 13, 17–20]. In other studies, employment [10, 17, 18] and marital status [10, 21] are also significantly associated with higher health literacy scores, which supports our findings. Given that education level was the strongest predictor of health literacy, it is essential to consider the necessity of developing simplified written, audio, or video educational materials tailored to an appropriate reading level to improve women’s health literacy. This is important because low health literacy may also influence the source and accuracy of the information received.

Aslo, 60% of women had never undergone mammography. According to national breast cancer control and screening guidelines, women are recommended to begin screening mammography at age 40 [18]. Participation in regular breast cancer screening is advised as the best method to detect potential cancerous growths at the earliest stage, thereby reducing cancer progression and mortality [22]. The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) has set a goal to achieve at least 70% adherence to mammography screening. In the study by Loewen et al., 79.3% of participants report timely screening, and only 5.5% had never been screened [22]. Other researchers have reported that 70% [12] and 88% [17] of women had never undergone screening mammography. Rakhshkhorshid et al. note that none of their participants perform a mammographic screening [18]. Therefore, the causes of low participation in screening mammography are an important issue that should be addressed by healthcare providers and policymakers. Some probable causes for not undergoing screening mammography include a lack of knowledge about mammography, unawareness of service locations, fear of radiation, fear of pain, fear of positive results, inconvenient service times, and lack of time [7].

Nearly 70% of the women reported having undergone a Pap smear. Ramaswamy et al. [13] and Rakhshani et al. [17] report that 67% and 53% of their participants undergo a Pap smear, respectively. Although the percentage of women performing Pap smears is higher in our study, further investigation focusing on the barriers to attending Pap smear screenings is necessary.

No association was found between health literacy and undergoing mammography or Pap smears. The results of Goto et al. align with our findings [23]. In the study by Rakhshani et al. [17], there is a significant correlation between health literacy and performing Pap smears; however, no correlation is found between health literacy and undergoing mammography. Given that some studies [5, 7, 24] have reported a significant correlation between health literacy and performing both mammograms and Pap smears, further investigation is needed that focuses on the barriers and reasons for non-adherence to these screenings. Additionally, the impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, which has led to a reduction in participation rates across all types of cancer screening programs—even after its control—must be acknowledged.

There was no association between age and health literacy, which aligns with the findings of Rakhshani et al. [17]. In the studies by Haghighi et al. [25] and Cudjoe et al. [26], a significant reverse correlation is shown between age and health literacy. A possible explanation for this could be that poor literacy associated with increasing age may result from reduced cognitive function and sensory abilities [19]. In contrast, the studies by Barati et al. [27] and Sun et al. [20] found that older age is significantly associated with higher cancer screening health literacy. Given the discrepancies in the results of these studies, further research is warranted to systematically investigate how age influences cancer screening health literacy among women.

The researcher found few studies that investigated the health literacy of breast and cervical cancer together. Therefore, we compared our results with existing similar studies related to health literacy in breast and cervical cancer screening. Additionally, since this study was cross-sectional, causality cannot be assumed when addressing the relationship between cancer screening health literacy and demographic characteristics.

Given that half of the participants did not have adequate health literacy and that education level was the strongest predictor of health literacy, health policymakers and healthcare providers should consider interventions based on demographic characteristics. This may include revising and simplifying teaching materials, as well as incorporating oral, pictorial, and written materials in the form of posters and pamphlets to enhance health literacy skills in the community. Additionally, promoting the communication skills of healthcare providers should also be taken into account.

Conclusion

Half of the participants do not have adequate health literacy and education level is the strongest predictor of health literacy.

Acknowledgments: We would like to sincerely thank the family health unit of the provincial health center, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran.

Ethical Permissions: The present study was ethically approved by the Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research (IR.YUMS.REC.1401.165).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution: Ghodsi N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Manzouri L (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (50%); Mousavizadeh A (Third Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Moradi-Joo M (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (10%)

Funding/Support: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Keywords:

References

1. Ministry of Health and Medical Education. National report of the national cancer registration program in 2018. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2018. [Persian] [Link]

2. Council of Writers headed by Yari P. Epidemiology reference of common diseases of Iran (Volume 3). Tehran: Gap; 2021. p. 39-52. [Persian] [Link]

3. Ritchie D, Van Hal G, Van Den Broucke S. Factors affecting intention to screen after being informed of benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: A study in 5 European countries in 2021. Arch Public Health. 2022;80(1):143. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13690-022-00902-6]

4. Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2019; 393(10167):169-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32470-X]

5. Baccolini V, Isonne C, Salerno C, Giffi M, Migliara G, Mazzalai E, et al. The association between adherence to cancer screening programs and health literacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2022;155:106927. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106927]

6. Javadzade SH, Sharifirad G, Radjati F, Mostafavi F, Reisi M, Hasanzade A. Relationship between health literacy, health status, and healthy behaviors among older adults in Isfahan, Iran. J Educ Health Promot. 2012;1:31. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.100160]

7. Poon PKM, Tam KW, Lam T, Luk AKC, Chu WCW, Cheung P, et al. Poor health literacy associated with stronger perceived barriers to breast cancer screening and overestimated breast cancer risk. Front Oncol. 2023;12:1053698. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fonc.2022.1053698]

8. Elobaid YE, Aw TC, Grivna M, Nagelkerke N. Breast cancer screening awareness, knowledge, and practice among arab women in the United Arab Emirates: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105783. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0105783]

9. Izanloo A, Ghaffarzadehgan K, Khoshroo F, Erfani Haghiri M, Izanloo S, Samiee M, et al. Knowledge and attitude of women regarding breast cancer screening tests in Eastern Iran. Ecancermedicalscience. 2018;12:806. [Link] [DOI:10.3332/ecancer.2018.806]

10. Danaei M, Asadsangabi Motlagh K, Momeni M. Investigating the status of health literacy and its predictive factors in women with breast cancer referring to teaching hospitals of Javad Al-Aemeh University and Clinic in Kerman 2021. J TOLOO-E-BEHDASHT. 2023;21(5):21-33. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.18502/tbj.v21i5.11747]

11. Kendir C, Kartal M. Health literacy levels affect breast cancer knowledge and screening attitudes of women in Turkey: A descriptive study. Turk J Public Health. 2019;17(2):183-94. [Turkish] [Link]

12. Rajabi R, Abedi P, Arban M, Maraghi E. Effects of education via WhatsApp vs compact disk on health literacy and behavior of middle-aged women about screening methods of breast cancer. Iran Q J Breast Dis. 2021;14(3):12-22. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.30699/ijbd.14.3.12]

13. Ramaswamy M, Lee J, Wickliffe J, Allison M, Emerson A, Kelly PJ. Impact of a brief intervention on cervical health literacy: A waitlist control study with jailed women. Prev Med Rep. 2017;6:314-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.04.003]

14. Emerson AM, Smith S, Lee J, Kelly PJ, Ramaswamy M. Effectiveness of a Kansas City, jail-based intervention to improve cervical health literacy and screening, one-year post-intervention. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34(1):87-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0890117119863714]

15. Ghanbari A, Rahmatpour P, Khalili M, Mokhtari N. Health literacy and its relationship with cancer screening behaviors among the employees of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. J Health Care. 2017;18(4):306-15. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.5812/semj.58665]

16. Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Williams AE, Greene SM, Gaglio B, Field TS, et al. Health literacy and cancer prevention: Two new instruments to assess comprehension. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(1):54-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2011.12.009]

17. Rakhshani T, Khiyali Z, Mirzaei M, Kamyab A, Jeihooni AK. Health literacy and breast and cervical cancer screening behaviors in women. J Educ Community Health. 2023;10(2):87-92. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/jech.2023.A-10-110-16]

18. Rakhshkhorshid M, Navaee M, Nouri N, Safarzaii F. The association of health literacy with breast cancer knowledge, perception and screening behavior. Eur J Breast Health. 2018;14(3):144-7. [Link] [DOI:10.5152/ejbh.2018.3757]

19. Batooli Z, Mohamadloo A. Health literacy of breast cancer and its related factors in Kashanian women: Breast cancer health literacy. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2022;31(3):16-23. [Link]

20. Sun CA, Chepkorir J, Jennifer Waligora Mendez K, Cudjoe J, Han HR. A descriptive analysis of cancer screening health literacy among black women living with HIV in Baltimore, Maryland. Health Lit Res Pract. 2022;6(3):e175-81. [Link] [DOI:10.3928/24748307-20220616-01]

21. McCormack L, Bann C, Squiers L, Berkman ND, Squire C, Schillinger D, et al. Measuring health literacy: A pilot study of a new skills-based instrument. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 2):51-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2010.499987]

22. Loewen OK, Sandila N, Shen-Tu G, Vena JE, Yang H, Patterson K, et al. Patterns and predictors of adherence to breast cancer screening recommendations in Alberta's Tomorrow Project. Prev Med Rep. 2022;30:102056. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.102056]

23. Goto E, Ishikawa H, Okuhara T, Kiuchi T. Relationship between health literacy and adherence to recommendations to undergo cancer screening and health-related behaviors among insured women in Japan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(12):3409-13. [Link] [DOI:10.31557/APJCP.2018.19.12.3409]

24. Rutherford EJ, Kelly J, Lehane EA, Livingstone V, Cotter B, Butt A, et al. Health literacy and the perception of risk in a breast cancer family history clinic. Surgeon. 2018;16(2):82-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.surge.2016.06.003]

25. Haghighi ST, Lamyian M, Granpaye L. Assessment of the level of health literacy among fertile Iranian women with breast cancer. Electron Physician. 2015;7(6):1359-64. [Link]

26. Cudjoe J, Delva S, Cajita M, Han HR. Empirically tested health literacy frameworks. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020;4(1):e22-44. [Link] [DOI:10.3928/24748307-20191025-01]

27. Barati M, Amirzargar MA, Bashirian S, Kafami V, Mousali AA, Moeini B. Psychological predictors of prostate cancer screening behaviors among men over 50 years of age in Hamadan: Perceived threat and efficacy. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2016;9(4):e4144. [Link] [DOI:10.17795/ijcp-4144]