Volume 6, Issue 3 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(3): 169-175 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: (IR.YUMS.REC.1400.136

History

Received: 2025/05/28 | Accepted: 2025/07/6 | Published: 2025/07/18

Received: 2025/05/28 | Accepted: 2025/07/6 | Published: 2025/07/18

How to cite this article

Tamoradi E, Afrasiabifar A, Ghadimimoghadam A, Salari M. Effect of Lullaby Music on Infantile Colic. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (3) :169-175

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-435-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-435-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Student Research Committee, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- Department of Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

3- Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- Department of Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

3- Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (308 Views)

Introduction

Pain is an unpleasant internal sensation generated by an early warning neurophysiological defense system to identify and minimize exposure to damaging or noxious stimuli [1]. Infantile colic (IC) is a gastrointestinal dysfunction that affects 10-40% of infants in the first three months of life. The prevalence of this condition varies between populations, with approximately 1 in 5 Iranian infants meeting the criteria for infantile colic [2]. The overt signs and symptoms of colic in infants typically include intense crying, a flushed face, difficulty passing gas from the intestines, abdominal distension, difficulty defecating, leg dragging, and arching of the back [3]. Colic may have negative short- and long-term consequences [4]. There is evidence of long-term adverse effects on infant behavior, sleep, and allergies, and it has been linked to disrupted parent-infant interactions, child abuse, frequent abdominal pain, migraines, hyperactivity, and increased learning difficulties in children with a history of colic [5, 6].

Several treatments, including sucrose, probiotics, herbal teas, changes to infant formula, swaddling, pacifiers, vibration or massage with oils, and spinal manipulation in some cases, as well as the elimination of cow’s milk and its proteins from the diets of breastfeeding mothers with breastfed infants, or the use of hypoallergenic formulas, which may reduce colic, have been studied; however, no treatment has been proven to be consistently effective [3, 7-9]. Due to the lack of effective medical treatments, infant colic drives desperate mothers to seek complementary and alternative therapies [10]. Melatonin concentrations can provide relaxation to both mother and infant [11]. Other research also supports the positive effects of natural childbirth and play therapy in reducing colic crises [12]. Given the young age of infants with colic, non-pharmacological treatment strategies, including kangaroo care, have generally been effective in reducing infant colic pain and improving physiological symptoms [13]. Additionally, maternal lullabies can reduce infant stress and provide comfort and relaxation to mothers after delivery [14]. Music therapy has also been shown to improve well-being, communication, sociability, and effective emotional expression in patients with depression, autism spectrum disorder, or other forms of cognitive dysfunction [15]. Music is a powerful sensory stimulus that produces physiological, psychological, and social effects [16]. Listening to music has been reported to be effective in reducing pain, stress, and anxiety, and in lowering cortisol levels in clinical studies [17]. The positive effects of music on children’s development, performance, and various skills have also been demonstrated [18]. From an early age, children respond significantly to music and its basic components, such as melody, harmony, rhythm, and dynamics [19]. The shared experience of performing or listening to music can be beneficial for health and well-being and is used to facilitate the rehabilitation of patients with neurological conditions and mood disorders, as well as to serve as an adjunct therapy for postoperative recovery [20].

Human and animal studies have shown that auditory experience also influences early brain development and that musical learning begins before birth. Music perception can activate various limbic and paralimbic structures and improve network connectivity in both children and adults. Music modulates synaptic plasticity and enhances neural processes, neural learning, and brain rewiring in animals and humans [21]. Music provides an enriched environment for the brain by increasing the sprouting of numerous nerve cell branches, or dendrites, which are essential for synaptic plasticity [22]. This leads to widespread benefits in various non-musical skills, such as speech perception in noise, auditory attention, and auditory working memory [23]. Studies show that music affects the metabolism of nerve cells by secreting various types of neurotransmitters in the central and peripheral nervous systems, increasing the production of nerve cells [24]. This process leads to the creation of feelings in the subcortical areas of the brain, activating the hypothalamus and autonomic nervous system, and secreting the arousal hormones noradrenaline and cortisol [25]. Additionally, it creates an endorphinergic response that can be blocked by naloxone, a common drug antagonist [26].

Van Der Heijden et al. found that listening to recorded music provided a useful distraction for children in pain in the emergency room [27]. Kasuya-Ueba et al. also found that children’s cognitive abilities to control or shift attention were significantly improved after a music intervention [16]. Prenatal music and singing interventions can be easily implemented and can also improve maternal mood and support maternal-infant bonding [17, 28, 29].

Considering the therapeutic effects of music on pain reduction, the different types of colic pain, and the lack of studies examining the effect of lullaby music alone on colic in infants, as well as the affordable, easy, accessible, and uncomplicated use of music, this study aimed to determine the effect of lullaby music on pain control and crying intensity in infants with colic.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and sample

This quasi-experimental controlled study included two groups: an intervention group and a control group, and pre- and post-intervention data were compared between the groups. The study was conducted in 2021 at a specialized pediatric clinic in Yasuj, Iran.

The sample consisted of eligible infants referred to a pediatric clinic in Yasuj, southern Iran. Inclusion criteria included a gestational age greater than 36 weeks, an age of less than four months at the time of the study, a birth weight greater than 2500g, an age of 6-16 weeks, the absence of other disorders and diseases, and a final diagnosis of infantile colic. Exclusion criteria included a lack of informed consent to participate in the study, infant sensitivity to lactose, and failure to meet the inclusion criteria.

The sample size was estimated using G*Power software, considering an alpha level of 0.05 (95% confidence level) and a beta level of 0.2 (80% power), with an effect size (minimum clinically significant difference) of 0.6. This resulted in 45 individuals in each of the intervention and control groups, totaling 90 participants. Eligible samples were selected using non-probability convenience sampling and then randomly assigned to one of the two groups (45 participants in each group) based on block random assignment. Since there were two groups, the number of groups was multiplied by 2 (i.e., 2x2=4) to increase the number of blocks in the block random assignment. Consequently, the number of blocks was determined based on the factorial rule, resulting in 24 blocks, with each block containing four samples: two from each group. Initially, by multiplying the number 2 by the number of groups studied (due to having both an intervention group and a control group), blocks of size 4 participants were established. Then, using the factorial rule (4!=1×2×3×4=24), the total number of 24 blocks was obtained, and the arrangement of each participant was designated with the letters A, B, C, and D.

Instrument

A demographic information form was used to collect data, including age, sex, weight, type of feeding (formula or breast milk), employment status, and the mother’s education level. The Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) Scale was employed to assess pain severity, while the Infant Colic-Related Crying Scale (ABC) was used to evaluate colic pain.

The FLACC Scale includes five domains: facial reactions, leg position, activity or movement, crying, and comfortability. Each of these domains is assigned a score of 0 to 2, and the final score is the sum of the domain scores. A score of zero indicates no pain, while a score of 10 indicates severe pain. Additionally, the total score is classified into three categories: 0-3 (mild pain), 4-6 (moderate pain), and 7-10 (severe pain) [30]. The validity and reliability of this tool have been confirmed by researchers in Canada [31]. This tool has also been utilized in various studies in Iran [32, 33].

The ABC Scale consists of three items: tone or initial intensity of crying (A), with options of no (0) and yes (2) (more than 400 Hz); bursty and rhythmic crying (B), with options of no (0) and yes (2); and constancy and continuity of crying (C). These three items were selected because they are related to the level of pain, and the score range for each item is 0 to 2, resulting in an overall score range of 0 to 6. The sum of the scores from these three items represents the final score. The validity and reliability of this tool have been confirmed in Italy [34]. This tool has also been used in various studies in Iran [35, 36].

Procedure

The intervention used was lullaby music. After the definitive diagnosis of infantile colic by a pediatrician, written informed consent was obtained from parents after a full explanation of the study’s objectives, and unconditional withdrawal was emphasized at each stage of the study. Necessary permits were obtained from Yasuj University of Medical Sciences and the Vice-Chancellor for Research. The mothers of the infants were asked to record the crying and symptoms of the child daily, following the previous instructions provided by the physician and researcher, which were explained to them during the child’s first visit. For children in the intervention group, in addition to the doctor’s routine instructions, lullaby music was played to the child nightly for 4 weeks during the day as needed when the child was crying due to colic. The recorded music of the “Night Sparrow Lullaby,” suitable for infants (Good Night Little Music at 9 o’clock on the National Radio of Iran), could be played on devices such as a Walkman, CD player, computer, and mobile phone. As soon as the infant started crying, the mothers were instructed to place the music player within 30 cm of the child, ensuring the volume was set to a frequency equal to or less than 80 dB with medium or lower intensity [37], as determined by sound meter software or a sound meter, and to continue playing the music until the infant calmed down.

A data collection form was provided to the parents of the infants, and they were asked to record the number of times the infant cried due to colic in 24 hours, as well as the duration of crying in minutes during each colic attack. In the control group, routine infant colic treatments, including dimethicone drops or Colic EZ drops, were used and monitored for four weeks. This routine treatment was also administered to the intervention group.

After 28 days of intervention, parents of both groups were asked to complete the pain and crying intensity scales again and to attend the doctor’s office for a re-evaluation and examination of the child. The outcomes of behavioral reactions due to infant colic included crying intensity, duration of crying, and pain intensity.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25 software with both descriptive and inferential statistics, considering a 95% confidence interval and p<0.05. For comparisons between groups regarding outcomes, the results of independent t-tests were reported. To assess the normal distribution of scores, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed, and indicated the normal distribution of scores.

Findings

Ninety children participated in the two groups, intervention and control (45 each), and remained in the study until the end. The highest percentage of 48.9% (44 children) were in the age group of 42-65 days, and their overall mean age was reported to be 70.05±21.23 days. The highest frequency of 56.7% (46 children) were female. The overall mean weight of the children was 5275.55±906.32g (ranging from 3200 to 7200g).

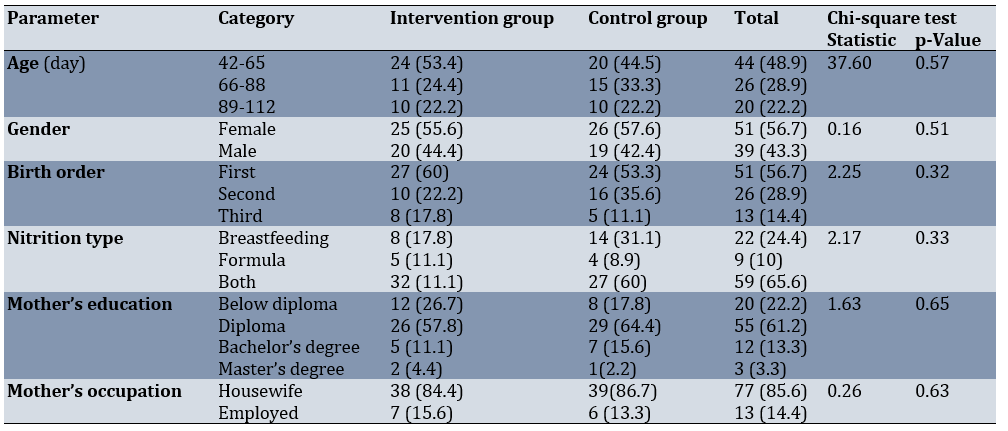

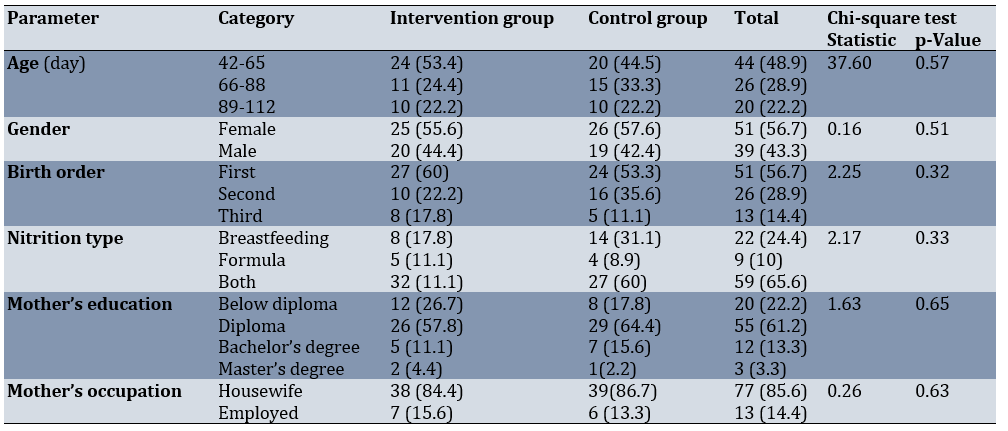

In terms of children’s nutrition, 65.6% (59 children) were mixed-fed (breast milk and formula), while 24.4% (22 children) were exclusively breastfed. A majority of 61.2% (55 parents) of the children studied had a diploma or higher education. Additionally, 85.6% (77 mothers) were housewives, while the remainder were employed. In terms of demographic characteristics, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups studied (p<0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups before the intervention

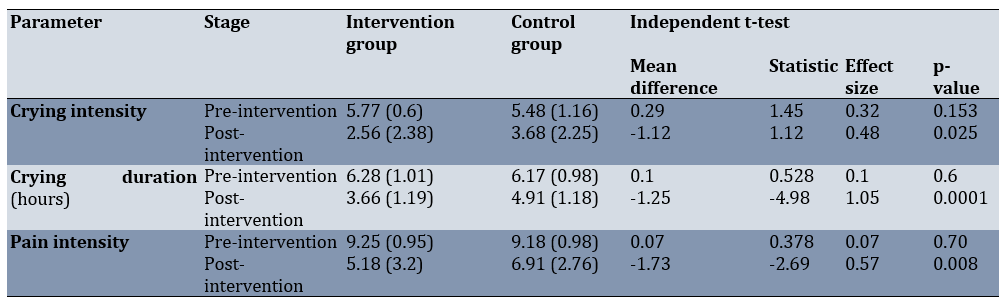

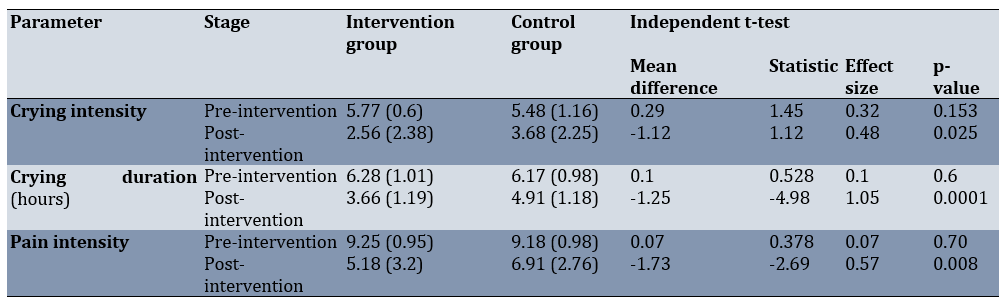

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated a normal distribution of the data. There was no statistically significant difference in the intensity and duration of crying, nor in pain intensity, between the intervention and control groups before the intervention. However, after the intervention, there were statistically significant differences in crying intensity (p=0.025), duration of crying (p=0.0001), and pain intensity (p=0.008) between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of behavioral reactions caused by infant colic between the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effect of music therapy on infant colic. The samples were homogeneous (intervention and control groups) at the beginning of the study concerning demographic factors, crying intensity and duration, and pain intensity. However, after the lullaby music intervention, the intensity and duration of crying, as well as the intensity of pain due to colic in infants, significantly decreased. Therefore, the observed changes in pain levels and crying intensity after the intervention could be attributed to the effect of lullaby music.

Similar to the present study, Ravikumar et al. investigated the effect of vestibular stimulation with an Indian hammock compared to musical intervention in preventing infant colic in infants. They demonstrated that both vestibular stimulation with an Indian hammock and musical intervention are effective in reducing the intensity of crying caused by colic in infants [38]. Other studies have also confirmed a reduction in infant colic crying during the use of music [39], as well as a decrease in crying intensity following mothers’ use of lullabies for their infants, which improved their interactive behaviors with their infants [28]. Although the type of music differs from lullabies, it appears that music programs can enhance mother-infant interaction, especially for mothers living in stressful or negative environments.

The crying time also decreased after the lullaby music intervention. In the study by Jalilolqadr et al. on the effect of music on monitoring the growth of low birth weight infants, the use of music is found to improve sleep time and the duration of relaxation, which aligns with the present study, as both studies had a duration of 28 days. However, other studies suggest that exposure to low-intensity sound (less than 70 dB) may be beneficial during sleep [37]. Keith et al. also demonstrate a significant reduction in the frequency and duration of inconsolable crying episodes as a result of the music intervention, along with improvements in physiological measures including heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and mean arterial pressure [40]. This finding is consistent with the present study regarding the reduction in the duration of inconsolable crying. Sezici and Yigit confirm a significant reduction in the duration of daily crying in colicky infants following exposure to white noise compared to rocking, as well as an increase in their sleep duration [41]. Bağli et al. also show that premature infants who listen to lullabies and classical music are more likely to have higher cerebral oxygen levels and greater comfort during procedures. Thus, healthcare professionals should encourage parents to have their premature infants listen to lullabies and classical music [42].

The intensity of colic pain in the intervention group decreased after the intervention. Huang et al. examined the effect of music therapy on pain in infants undergoing mechanical ventilation after cardiac surgery and showed that music therapy reduces the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) scores and shortens the length of stay in the intensive care unit [43]. The reason for this concordance may be attributed to the similar duration and frequency of daily music playback in both studies. In the study by Rossi et al., the reduction in pain perception with music is investigated in healthy infants by comparing different musical tones and monitoring heart rate. They found that exposure to music and heart rate recordings induces calmer behavioral parameters and short-term changes in physiological parameters in healthy infants undergoing potentially painful procedures [44].

In line with the present study, Ravikumar et al. showed that vestibular stimulation with an Indian hammock and music intervention are effective in reducing colic pain in infants [38]. Sabzevari et al. studied the effect of music on pain and vital signs in children after endoscopy and demonstrated that playing music for children during the procedure can reduce their pain and anxiety, stabilize their vital signs, and lead to greater cooperation during endoscopy [45]. In this case, nightly lullaby music was used as an intervention. Overall, the effect of music in both studies was consistent and positive in reducing pain. In the study by Alidadian et al., the use of lullabies along with kangaroo care as non-pharmacological interventions can help control infant pain and assist nurses working in the intensive care unit in maintaining and improving physiological parameters [13]. Additionally, in the study by Sağkal Midilli & Ergin, the use of white noise and lullabies also reduces pain in infants [46].

Karaca and Guner showed that musical mobile toys reduce fear and anxiety in preschool children undergoing intravenous infusion in a pediatric emergency department, although there was no statistically significant difference between the control and intervention groups [47]. In the same context, Wulff et al. demonstrated that listening to music, especially singing, has promising effects on maternal health and the mother’s sense of closeness to the fetus during pregnancy, which in turn reduces maternal stress [17]. As a result, this has a positive effect on creating peace in the baby and reducing infant colic [48, 49]. Therefore, singing can be a useful strategy or tool for managing colic. Although the target population, study types, types of music, and protocols of the aforementioned interventions differ from the present study, the results indicate a positive effect of music in clinical research. Iranian doctors have also considered strategies such as massage with special oils, improving maternal and infant nutrition, and using sleeping pills to reduce gas production in the digestive tract and its side effects [7]. However, recent research, which takes into account the potential side effects of pharmacological interventions in the high-risk age group of infancy [8], recommends multisensory stimulation that integrates auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and tactile stimuli for non-pharmacological pain management due to its favorable safety profile and analgesic efficacy [50]. Applying these recommendations along with music may help to better treat infantile colic.

This study also had limitations. The use of self-reporting can be influenced by the mental state of the infant’s caregiver at the time of completing the questionnaire, as well as errors associated with the self-reporting method and the individual’s mental state during the completion of the questionnaire, which may introduce bias into the results. Blinding was not possible in this study. Additional limitations included an extended sampling period due to the coronavirus pandemic and the resulting social restrictions, which may have affected the study’s results.

Mother’s lullaby music can be recommended to mothers and neonatal wards due to its accessibility and low cost. The following suggestions are made for further research: 1) Using the mother’s favorite music during pregnancy for infants with colic after birth and examining the results in future studies; 2) Comparing mother’s lullaby music with classical music and folk music in the treatment of infant colic in further research; and 3) Implementing music therapy during the mother’s pregnancy and measuring its effects on infant colic after birth.

Conclusion

Lullaby music reduces pain intensity, decrease crying intensity, reduce crying duration, and increase the duration of calmness in infants with colic.

Acknowledgments: This paper is derived from a master’s thesis by Esmat Tamoradi in the MSc program of pediatric nursing. The authors would like to thank the Research Deputy of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences for financially supporting this project, as well as all the children and their mothers who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Ethical permissions: Data were collected following approval from the Ethics Committee for Biological Research of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences in Iran (IR.YUMS.REC.1400.136).

Authors' Contribution: Tamoradi M (First Author), Main Researcher (30%); Afrasiabifar A (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (22%); Ghadimi Moghadam A (Third Author), Assistant Researcher, methodologist (23%); Salari M (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (25%)

Funding/Support: The cost of this research project was funded by Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

Pain is an unpleasant internal sensation generated by an early warning neurophysiological defense system to identify and minimize exposure to damaging or noxious stimuli [1]. Infantile colic (IC) is a gastrointestinal dysfunction that affects 10-40% of infants in the first three months of life. The prevalence of this condition varies between populations, with approximately 1 in 5 Iranian infants meeting the criteria for infantile colic [2]. The overt signs and symptoms of colic in infants typically include intense crying, a flushed face, difficulty passing gas from the intestines, abdominal distension, difficulty defecating, leg dragging, and arching of the back [3]. Colic may have negative short- and long-term consequences [4]. There is evidence of long-term adverse effects on infant behavior, sleep, and allergies, and it has been linked to disrupted parent-infant interactions, child abuse, frequent abdominal pain, migraines, hyperactivity, and increased learning difficulties in children with a history of colic [5, 6].

Several treatments, including sucrose, probiotics, herbal teas, changes to infant formula, swaddling, pacifiers, vibration or massage with oils, and spinal manipulation in some cases, as well as the elimination of cow’s milk and its proteins from the diets of breastfeeding mothers with breastfed infants, or the use of hypoallergenic formulas, which may reduce colic, have been studied; however, no treatment has been proven to be consistently effective [3, 7-9]. Due to the lack of effective medical treatments, infant colic drives desperate mothers to seek complementary and alternative therapies [10]. Melatonin concentrations can provide relaxation to both mother and infant [11]. Other research also supports the positive effects of natural childbirth and play therapy in reducing colic crises [12]. Given the young age of infants with colic, non-pharmacological treatment strategies, including kangaroo care, have generally been effective in reducing infant colic pain and improving physiological symptoms [13]. Additionally, maternal lullabies can reduce infant stress and provide comfort and relaxation to mothers after delivery [14]. Music therapy has also been shown to improve well-being, communication, sociability, and effective emotional expression in patients with depression, autism spectrum disorder, or other forms of cognitive dysfunction [15]. Music is a powerful sensory stimulus that produces physiological, psychological, and social effects [16]. Listening to music has been reported to be effective in reducing pain, stress, and anxiety, and in lowering cortisol levels in clinical studies [17]. The positive effects of music on children’s development, performance, and various skills have also been demonstrated [18]. From an early age, children respond significantly to music and its basic components, such as melody, harmony, rhythm, and dynamics [19]. The shared experience of performing or listening to music can be beneficial for health and well-being and is used to facilitate the rehabilitation of patients with neurological conditions and mood disorders, as well as to serve as an adjunct therapy for postoperative recovery [20].

Human and animal studies have shown that auditory experience also influences early brain development and that musical learning begins before birth. Music perception can activate various limbic and paralimbic structures and improve network connectivity in both children and adults. Music modulates synaptic plasticity and enhances neural processes, neural learning, and brain rewiring in animals and humans [21]. Music provides an enriched environment for the brain by increasing the sprouting of numerous nerve cell branches, or dendrites, which are essential for synaptic plasticity [22]. This leads to widespread benefits in various non-musical skills, such as speech perception in noise, auditory attention, and auditory working memory [23]. Studies show that music affects the metabolism of nerve cells by secreting various types of neurotransmitters in the central and peripheral nervous systems, increasing the production of nerve cells [24]. This process leads to the creation of feelings in the subcortical areas of the brain, activating the hypothalamus and autonomic nervous system, and secreting the arousal hormones noradrenaline and cortisol [25]. Additionally, it creates an endorphinergic response that can be blocked by naloxone, a common drug antagonist [26].

Van Der Heijden et al. found that listening to recorded music provided a useful distraction for children in pain in the emergency room [27]. Kasuya-Ueba et al. also found that children’s cognitive abilities to control or shift attention were significantly improved after a music intervention [16]. Prenatal music and singing interventions can be easily implemented and can also improve maternal mood and support maternal-infant bonding [17, 28, 29].

Considering the therapeutic effects of music on pain reduction, the different types of colic pain, and the lack of studies examining the effect of lullaby music alone on colic in infants, as well as the affordable, easy, accessible, and uncomplicated use of music, this study aimed to determine the effect of lullaby music on pain control and crying intensity in infants with colic.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and sample

This quasi-experimental controlled study included two groups: an intervention group and a control group, and pre- and post-intervention data were compared between the groups. The study was conducted in 2021 at a specialized pediatric clinic in Yasuj, Iran.

The sample consisted of eligible infants referred to a pediatric clinic in Yasuj, southern Iran. Inclusion criteria included a gestational age greater than 36 weeks, an age of less than four months at the time of the study, a birth weight greater than 2500g, an age of 6-16 weeks, the absence of other disorders and diseases, and a final diagnosis of infantile colic. Exclusion criteria included a lack of informed consent to participate in the study, infant sensitivity to lactose, and failure to meet the inclusion criteria.

The sample size was estimated using G*Power software, considering an alpha level of 0.05 (95% confidence level) and a beta level of 0.2 (80% power), with an effect size (minimum clinically significant difference) of 0.6. This resulted in 45 individuals in each of the intervention and control groups, totaling 90 participants. Eligible samples were selected using non-probability convenience sampling and then randomly assigned to one of the two groups (45 participants in each group) based on block random assignment. Since there were two groups, the number of groups was multiplied by 2 (i.e., 2x2=4) to increase the number of blocks in the block random assignment. Consequently, the number of blocks was determined based on the factorial rule, resulting in 24 blocks, with each block containing four samples: two from each group. Initially, by multiplying the number 2 by the number of groups studied (due to having both an intervention group and a control group), blocks of size 4 participants were established. Then, using the factorial rule (4!=1×2×3×4=24), the total number of 24 blocks was obtained, and the arrangement of each participant was designated with the letters A, B, C, and D.

Instrument

A demographic information form was used to collect data, including age, sex, weight, type of feeding (formula or breast milk), employment status, and the mother’s education level. The Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) Scale was employed to assess pain severity, while the Infant Colic-Related Crying Scale (ABC) was used to evaluate colic pain.

The FLACC Scale includes five domains: facial reactions, leg position, activity or movement, crying, and comfortability. Each of these domains is assigned a score of 0 to 2, and the final score is the sum of the domain scores. A score of zero indicates no pain, while a score of 10 indicates severe pain. Additionally, the total score is classified into three categories: 0-3 (mild pain), 4-6 (moderate pain), and 7-10 (severe pain) [30]. The validity and reliability of this tool have been confirmed by researchers in Canada [31]. This tool has also been utilized in various studies in Iran [32, 33].

The ABC Scale consists of three items: tone or initial intensity of crying (A), with options of no (0) and yes (2) (more than 400 Hz); bursty and rhythmic crying (B), with options of no (0) and yes (2); and constancy and continuity of crying (C). These three items were selected because they are related to the level of pain, and the score range for each item is 0 to 2, resulting in an overall score range of 0 to 6. The sum of the scores from these three items represents the final score. The validity and reliability of this tool have been confirmed in Italy [34]. This tool has also been used in various studies in Iran [35, 36].

Procedure

The intervention used was lullaby music. After the definitive diagnosis of infantile colic by a pediatrician, written informed consent was obtained from parents after a full explanation of the study’s objectives, and unconditional withdrawal was emphasized at each stage of the study. Necessary permits were obtained from Yasuj University of Medical Sciences and the Vice-Chancellor for Research. The mothers of the infants were asked to record the crying and symptoms of the child daily, following the previous instructions provided by the physician and researcher, which were explained to them during the child’s first visit. For children in the intervention group, in addition to the doctor’s routine instructions, lullaby music was played to the child nightly for 4 weeks during the day as needed when the child was crying due to colic. The recorded music of the “Night Sparrow Lullaby,” suitable for infants (Good Night Little Music at 9 o’clock on the National Radio of Iran), could be played on devices such as a Walkman, CD player, computer, and mobile phone. As soon as the infant started crying, the mothers were instructed to place the music player within 30 cm of the child, ensuring the volume was set to a frequency equal to or less than 80 dB with medium or lower intensity [37], as determined by sound meter software or a sound meter, and to continue playing the music until the infant calmed down.

A data collection form was provided to the parents of the infants, and they were asked to record the number of times the infant cried due to colic in 24 hours, as well as the duration of crying in minutes during each colic attack. In the control group, routine infant colic treatments, including dimethicone drops or Colic EZ drops, were used and monitored for four weeks. This routine treatment was also administered to the intervention group.

After 28 days of intervention, parents of both groups were asked to complete the pain and crying intensity scales again and to attend the doctor’s office for a re-evaluation and examination of the child. The outcomes of behavioral reactions due to infant colic included crying intensity, duration of crying, and pain intensity.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25 software with both descriptive and inferential statistics, considering a 95% confidence interval and p<0.05. For comparisons between groups regarding outcomes, the results of independent t-tests were reported. To assess the normal distribution of scores, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed, and indicated the normal distribution of scores.

Findings

Ninety children participated in the two groups, intervention and control (45 each), and remained in the study until the end. The highest percentage of 48.9% (44 children) were in the age group of 42-65 days, and their overall mean age was reported to be 70.05±21.23 days. The highest frequency of 56.7% (46 children) were female. The overall mean weight of the children was 5275.55±906.32g (ranging from 3200 to 7200g).

In terms of children’s nutrition, 65.6% (59 children) were mixed-fed (breast milk and formula), while 24.4% (22 children) were exclusively breastfed. A majority of 61.2% (55 parents) of the children studied had a diploma or higher education. Additionally, 85.6% (77 mothers) were housewives, while the remainder were employed. In terms of demographic characteristics, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups studied (p<0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups before the intervention

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated a normal distribution of the data. There was no statistically significant difference in the intensity and duration of crying, nor in pain intensity, between the intervention and control groups before the intervention. However, after the intervention, there were statistically significant differences in crying intensity (p=0.025), duration of crying (p=0.0001), and pain intensity (p=0.008) between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of behavioral reactions caused by infant colic between the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effect of music therapy on infant colic. The samples were homogeneous (intervention and control groups) at the beginning of the study concerning demographic factors, crying intensity and duration, and pain intensity. However, after the lullaby music intervention, the intensity and duration of crying, as well as the intensity of pain due to colic in infants, significantly decreased. Therefore, the observed changes in pain levels and crying intensity after the intervention could be attributed to the effect of lullaby music.

Similar to the present study, Ravikumar et al. investigated the effect of vestibular stimulation with an Indian hammock compared to musical intervention in preventing infant colic in infants. They demonstrated that both vestibular stimulation with an Indian hammock and musical intervention are effective in reducing the intensity of crying caused by colic in infants [38]. Other studies have also confirmed a reduction in infant colic crying during the use of music [39], as well as a decrease in crying intensity following mothers’ use of lullabies for their infants, which improved their interactive behaviors with their infants [28]. Although the type of music differs from lullabies, it appears that music programs can enhance mother-infant interaction, especially for mothers living in stressful or negative environments.

The crying time also decreased after the lullaby music intervention. In the study by Jalilolqadr et al. on the effect of music on monitoring the growth of low birth weight infants, the use of music is found to improve sleep time and the duration of relaxation, which aligns with the present study, as both studies had a duration of 28 days. However, other studies suggest that exposure to low-intensity sound (less than 70 dB) may be beneficial during sleep [37]. Keith et al. also demonstrate a significant reduction in the frequency and duration of inconsolable crying episodes as a result of the music intervention, along with improvements in physiological measures including heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and mean arterial pressure [40]. This finding is consistent with the present study regarding the reduction in the duration of inconsolable crying. Sezici and Yigit confirm a significant reduction in the duration of daily crying in colicky infants following exposure to white noise compared to rocking, as well as an increase in their sleep duration [41]. Bağli et al. also show that premature infants who listen to lullabies and classical music are more likely to have higher cerebral oxygen levels and greater comfort during procedures. Thus, healthcare professionals should encourage parents to have their premature infants listen to lullabies and classical music [42].

The intensity of colic pain in the intervention group decreased after the intervention. Huang et al. examined the effect of music therapy on pain in infants undergoing mechanical ventilation after cardiac surgery and showed that music therapy reduces the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) scores and shortens the length of stay in the intensive care unit [43]. The reason for this concordance may be attributed to the similar duration and frequency of daily music playback in both studies. In the study by Rossi et al., the reduction in pain perception with music is investigated in healthy infants by comparing different musical tones and monitoring heart rate. They found that exposure to music and heart rate recordings induces calmer behavioral parameters and short-term changes in physiological parameters in healthy infants undergoing potentially painful procedures [44].

In line with the present study, Ravikumar et al. showed that vestibular stimulation with an Indian hammock and music intervention are effective in reducing colic pain in infants [38]. Sabzevari et al. studied the effect of music on pain and vital signs in children after endoscopy and demonstrated that playing music for children during the procedure can reduce their pain and anxiety, stabilize their vital signs, and lead to greater cooperation during endoscopy [45]. In this case, nightly lullaby music was used as an intervention. Overall, the effect of music in both studies was consistent and positive in reducing pain. In the study by Alidadian et al., the use of lullabies along with kangaroo care as non-pharmacological interventions can help control infant pain and assist nurses working in the intensive care unit in maintaining and improving physiological parameters [13]. Additionally, in the study by Sağkal Midilli & Ergin, the use of white noise and lullabies also reduces pain in infants [46].

Karaca and Guner showed that musical mobile toys reduce fear and anxiety in preschool children undergoing intravenous infusion in a pediatric emergency department, although there was no statistically significant difference between the control and intervention groups [47]. In the same context, Wulff et al. demonstrated that listening to music, especially singing, has promising effects on maternal health and the mother’s sense of closeness to the fetus during pregnancy, which in turn reduces maternal stress [17]. As a result, this has a positive effect on creating peace in the baby and reducing infant colic [48, 49]. Therefore, singing can be a useful strategy or tool for managing colic. Although the target population, study types, types of music, and protocols of the aforementioned interventions differ from the present study, the results indicate a positive effect of music in clinical research. Iranian doctors have also considered strategies such as massage with special oils, improving maternal and infant nutrition, and using sleeping pills to reduce gas production in the digestive tract and its side effects [7]. However, recent research, which takes into account the potential side effects of pharmacological interventions in the high-risk age group of infancy [8], recommends multisensory stimulation that integrates auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and tactile stimuli for non-pharmacological pain management due to its favorable safety profile and analgesic efficacy [50]. Applying these recommendations along with music may help to better treat infantile colic.

This study also had limitations. The use of self-reporting can be influenced by the mental state of the infant’s caregiver at the time of completing the questionnaire, as well as errors associated with the self-reporting method and the individual’s mental state during the completion of the questionnaire, which may introduce bias into the results. Blinding was not possible in this study. Additional limitations included an extended sampling period due to the coronavirus pandemic and the resulting social restrictions, which may have affected the study’s results.

Mother’s lullaby music can be recommended to mothers and neonatal wards due to its accessibility and low cost. The following suggestions are made for further research: 1) Using the mother’s favorite music during pregnancy for infants with colic after birth and examining the results in future studies; 2) Comparing mother’s lullaby music with classical music and folk music in the treatment of infant colic in further research; and 3) Implementing music therapy during the mother’s pregnancy and measuring its effects on infant colic after birth.

Conclusion

Lullaby music reduces pain intensity, decrease crying intensity, reduce crying duration, and increase the duration of calmness in infants with colic.

Acknowledgments: This paper is derived from a master’s thesis by Esmat Tamoradi in the MSc program of pediatric nursing. The authors would like to thank the Research Deputy of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences for financially supporting this project, as well as all the children and their mothers who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Ethical permissions: Data were collected following approval from the Ethics Committee for Biological Research of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences in Iran (IR.YUMS.REC.1400.136).

Authors' Contribution: Tamoradi M (First Author), Main Researcher (30%); Afrasiabifar A (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (22%); Ghadimi Moghadam A (Third Author), Assistant Researcher, methodologist (23%); Salari M (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (25%)

Funding/Support: The cost of this research project was funded by Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

References

1. Woolf CJ. What is this thing called pain?. J Clin Investig. 2010;120(11):3742-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1172/JCI45178]

2. Pourmirzaiee MA, Famouri F, Moazeni W, Hassanzadeh A, Hajihashemi M. The efficacy of the prenatal administration of Lactobacillus reuteri LR92 DSM 26866 on the prevention of infantile colic: A randomized control trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179(10):1619-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00431-020-03641-4]

3. Karkhaneh M, Fraser L, Jou H, Vohra S. Effectiveness of probiotics in infantile colic: A rapid review. Paediatr Child Health. 2020;25(3):149-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/pch/pxz007]

4. Steutel NF, Benninga MA, Langendam MW, Korterink JJ, Indrio F, Szajewska H, et al. Developing a core outcome set for infant colic for primary, secondary and tertiary care settings: A prospective study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015418. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015418]

5. Sung V, D'Amico F, Cabana MD, Chau K, Koren G, Savino F, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri to treat infant colic: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20171811. [Link] [DOI:10.1542/peds.2017-1811]

6. Steutel NF, Benninga MA, Langendam MW, De Kruijff I, Tabbers MM. Reporting outcome measures in trials of infant colic. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(3):341-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/MPG.0000000000000412]

7. Asadi MH, Ashtiyani SC, Hossein Latifi SA. Evaluation of the infantile colic causes in Persian medicine. Iran J Neonatol. 2021;12(1):33-9. [Link]

8. Mohanty N, Shrivastava R. Infant colic revisited. Ann Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol ISPGHAN. 2024;6(4):58-62. [Link] [DOI:10.5005/jp-journals-11009-0170]

9. Long B, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M, Zehtabchi S. Lactobacillus reuteri for treatment of infant colic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(10):1059-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/acem.13977]

10. Oflu A, Bukulmez A, Gorel O, Acar B, Can Y, Ilgaz NC, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine experiences of mothers in the treatment of infantile colic. Sudan J Paediatr. 2020;20(1):49-57. [Link] [DOI:10.24911/SJP.106-1568897690]

11. Oliveira FS, Dieckman K, Mota D, Zenner AJ, Schleusner MA, Cecilio JO, et al. Melatonin in human milk: A scoping review. Biol Res Nurs. 2025;27(1):142-67. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/10998004241263100]

12. Devecigil N, Wade J. Colic as trauma release? A comparative exploration of play therapy in children with and without a history of colic. Int J Transpers Stud. 2024;43(1):9. [Link] [DOI:10.24972/ijts.2024.43.1-2.94]

13. Alidadian S, Naderifar M, Abbasi A, Navidian A, Mahmoodi N. Comparison of the effect of lullaby and kangaroo care on physiological criteria during heel lance in preterm neonates at the neonatal intensive care unit. Iran J Neonatol. 2021;12(4):40-7. [Link]

14. Selçuk AK, Karaarslan D, Ergin E, Salğin E. The effect of white noise and recorded lullaby during breastfeeding on newborn stress, mother's breastfeeding success, and comfort: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Nurs. 2025;81:e16-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2025.01.008]

15. Boasen J, Takeshita Y, Kuriki S, Yokosawa K. Spectral-spatial differentiation of brain activity during mental imagery of improvisational music performance using MEG. Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;12:156. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00156]

16. Kasuya-Ueba Y, Zhao S, Toichi M. The effect of music intervention on attention in children: Experimental evidence. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:757. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fnins.2020.00757]

17. Wulff V, Hepp P, Wolf OT, Balan P, Hagenbeck C, Fehm T, et al. The effects of a music and singing intervention during pregnancy on maternal well-being and mother-infant bonding: A randomised, controlled study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;303(1):69-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00404-020-05727-8]

18. Schaal NK, Politimou N, Franco F, Stewart L, Müllensiefen D. The German music@ home: Validation of a questionnaire measuring at home musical exposure and interaction of young children. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0235923. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0235923]

19. Cheever T, Taylor A, Finkelstein R, Edwards E, Thomas L, Bradt J, et al. NIH/Kennedy center workshop on music and the brain: Finding harmony. Neuron. 2018;97(6):1214-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.02.004]

20. Cox J. Music and the brain: A heartland of psychiatry?. BJPsych Int. 2017;14(2):27-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1192/S2056474000001719]

21. Haslbeck FB, Jakab A, Held U, Bassler D, Bucher HU, Hagmann C. Creative music therapy to promote brain function and brain structure in preterm infants: A randomized controlled pilot study. NeuroImage Clin. 2020;25:102171. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102171]

22. Vik BMD, Skeie GO, Specht K. Neuroplastic effects in patients with traumatic brain injury after music-supported therapy. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:177. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00177]

23. Steel MM, Polonenko MJ, Giannantonio S, Hopyan T, Papsin BC, Gordon KA. Music perception testing reveals advantages and continued challenges for children using bilateral cochlear implants. Front Psychol. 2020;10:3015. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03015]

24. Riyasi M, Dastgheib SS. Utilization of basic musical concepts to accelerate language acquisition in children after cochlear implantation. SHEFAYE KHATAM. 2013;1(3):49-53. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.shefa.1.3.49]

25. Arjmand HA, Hohagen J, Paton B, Rickard NS. Emotional responses to music: Shifts in frontal brain asymmetry mark periods of musical change. Front Psychol. 2017;8:241589. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02044]

26. Blum K, Simpatico T, Febo M, Rodriquez C, Dushaj K, Li M, et al. Hypothesizing music intervention enhances brain functional connectivity involving dopaminergic recruitment: Common neuro-correlates to abusable drugs. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(5):3753-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12035-016-9934-y]

27. Van Der Heijden MJE, Mevius H, Van Der Heijde N, Van Rosmalen J, Van As S, Van Dijk M. Children listening to music or watching cartoons during ER procedures: A RCT. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019;44(10):1151-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsz066]

28. Robertson AM, Detmer MR. The effects of contingent lullaby music on parent-infant interaction and amount of infant crying in the first six weeks of life. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;46:33-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2019.02.025]

29. Hugoson P, Haslbeck FB, Ådén U, Eulau L. Parental singing during kangaroo care: Parents' experiences of singing to their preterm infant in the NICU. Front Psychol. 2025;16:1440905. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1440905]

30. Sadeghi T, Mohammadi N, Shamshiri M, Bagherzadeh R, Hossinkhani N. Effect of distraction on children's pain during intravenous catheter insertion. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2013;18(2):109-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jspn.12018]

31. Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Burke C, Merkel S, Tait AR. The revised FLACC observational pain tool: Improved reliability and validity for pain assessment in children with cognitive impairment. Pediatr Anesth. 2006;16(3):258-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01773.x]

32. Unesi Z, Afshari G, Salari Dastgerd H, Gandomi M. The effect of ShotBlocker on vaccination pain in infants. J HAYAT. 2021;27(3):278-89. [Persian] [Link]

33. Farhadi A. The effect of topical tetracaine Gel%4 on pain reduction of DPT vaccine in 18 months infants. Nurs Midwifery J. 2012;10(4). [Persian] [Link]

34. Bellieni CV, Bagnoli F, Sisto R, Neri L, Cordelli D, Buonocore G. Development and validation of the ABC pain scale for healthy full-term babies. ACTA PAEDIATRICA. 2005;94(10):1432-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08035250510039919]

35. Sheidaei A, Abadi A, Nahidi F, Amini F, Zayeri F, Gazrani N. The effect of massage and shaking on infants with colicin a clinical trial concerning the misspecification. Tehran Univ Med J. 2021;79(1):33-41. [Persian] [Link]

36. Sheidaei A, Abadi A, Nahidi F, Zayeri F, Gazerani N. Effect of massage on severity of cries and sleep duration among infants who suffer infantile colic: A randomized clinical trial. PAJOOHANDE. 2015;20(3):141-8. [Persian] [Link]

37. Jalilolqadr Sh., Ashrafi M., Mahram M., Oveisi S. Effect of music on the growth monitoring of low birth weight newborns. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2021;14:100312. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijans.2021.100312]

38. Ravikumar S, Srinivasaraghavan R, Gunasekaran D, Sundar S, Soundararajan P. Vestibular stimulation with Indian hammock versus music intervention in the prevention of infantile colic in term infants: An open-labelled, randomized controlled trial. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2020;7(4):191-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijpam.2019.12.004]

39. Larson K, Ayllon T. The effects of contingent music and differential reinforcement on infantile colic. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28(2):119-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0005-7967(90)90024-D]

40. Keith DR, Russell K, Weaver BS. The effects of music listening on inconsolable crying in premature infants. J Music Ther. 2009;46(3):191-203. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jmt/46.3.191]

41. Sezici E, Yigit D. Comparison between swinging and playing of white noise among colicky babies: A paired randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(3-4):593-600. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jocn.13928]

42. Bağli E, Küçükoğlu S, Soylu H. The effect of lullabies and classical music on preterm neonates' cerebral oxygenation, vital signs, and comfort during orogastric tube feeding: A randomized controlled trial. Biol Res Nurs. 2024;26(2):181-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/10998004231202404]

43. Huang YL, Lei YQ, Xie WP, Cao H, Yu XR, Chen Q. Effect of music therapy on infants who underwent mechanical ventilation after cardiac surgery. J Card Surg. 2021;36(12):4460-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jocs.15976]

44. Rossi A, Molinaro A, Savi E, Micheletti S, Galli J, Chirico G, et al. Music reduces pain perception in healthy newborns: A comparison between different music tracks and recoded heartbeat. Early Hum Dev. 2018;124:7-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.07.006]

45. Sabzevari A, Kianifar H, Jafari SA, Saeidi M, Ahanchian H, Kiani MA, et al. The effect of music on pain and vital signs of children before and after endoscopy. Electron Physician. 2017;9(7):4801-5. [Link] [DOI:10.19082/4801]

46. Sağkal Midilli T, Ergin E. The effect of white noise and Brahms' lullaby on pain in infants during intravenous blood draw: A randomized controlled study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2023;29(2):148-54. [Link]

47. Karaca TN, Guner UC. The effect of music-moving toys to reduce fear and anxiety in preschool children undergoing intravenous insertion in a pediatric emergency department: A randomized clinical trial. J Emerg Nurs. 2022;48(1):32-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jen.2021.10.004]

48. Persico G, Antolini L, Vergani P, Costantini W, Nardi MT, Bellotti L. Maternal singing of lullabies during pregnancy and after birth: Effects on mother-infant bonding and on newborns' behaviour. Concurrent cohort study. Women Birth. 2017;30(4):e214-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.wombi.2017.01.007]

49. Savino F. Focus on infantile colic. ACTA PAEDIATRICA. 2007;96(9):1259-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00428.x]

50. Tao C, He C, Tang J, Li Y, Chen Y. Research progress on multisensory stimulation therapy for pain during retinopathy of prematurity screening. Front Pediatr. 2025;13:2025. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fped.2025.1623188]