Volume 6, Issue 3 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(3): 129-135 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.404

History

Received: 2025/05/7 | Accepted: 2025/06/20 | Published: 2025/07/1

Received: 2025/05/7 | Accepted: 2025/06/20 | Published: 2025/07/1

How to cite this article

Choheili H, Marashian F, Safarzadeh S, Asgari P. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and Schema Therapy on Emotion-Focused Coping Strategies and Craving in Individuals with Stimulant Substance Use Disorder. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (3) :129-135

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-436-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-436-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Campus (Ahv.C.), Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (202 Views)

Introduction

Stimulant use disorder, characterized by a pattern of compulsive use of substances such as methamphetamine, cocaine, and prescription stimulants, poses a significant global public health crisis [1]. The prevalence of this disorder is rising, leading to devastating consequences for individuals, families, and communities. From a clinical perspective, individuals with stimulant use disorder often present with a range of severe psychological and behavioral challenges, including a high risk of relapse, cognitive impairment, emotional dysregulation, and social and occupational dysfunction [2, 3]. The chronic nature of the disorder and its high comorbidity with other mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and personality disorders, further complicate treatment and recovery [4]. Effective interventions are therefore urgently needed to address the core mechanisms that perpetuate the cycle of addiction and relapse.

The ability to effectively manage stress and difficult emotional states is a critical determinant of successful recovery from addiction [5]. Coping strategies are the behavioral and psychological efforts individuals use to tolerate, reduce, or minimize stress. Research categorizes these strategies into two primary types, including problem-focused and emotion-focused coping [6]. Problem-focused coping involves actively addressing the source of stress, while emotion-focused coping focuses on regulating the emotional response to stress. In individuals with stimulant use disorder, maladaptive coping patterns, such as avoidance, denial, and wishful thinking, are prevalent and strongly associated with continued substance use and relapse [7, 8]. The over-reliance on emotion-focused coping (which can often be avoidant and passive) is particularly relevant in this population. Therapeutic interventions, therefore, must aim to modify these ineffective emotion-focused strategies.

Craving is an intense desire or urge to use a substance and is recognized as a central feature of stimulant use disorder [9]. It is a powerful predictor of relapse, often triggered by a complex interplay of internal and external cues, including stress, emotional states, and environmental stimuli [10]. Craving is a multifaceted phenomenon with neurobiological, psychological, and behavioral components. From a psychological perspective, craving can be understood as a conditioned response that becomes ingrained through repeated substance use, making it a formidable obstacle to sustained abstinence [11]. Given its direct link to relapse, effective treatment for stimulant use disorder must include strategies specifically designed to manage and reduce the intensity and frequency of craving.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), originally developed to prevent depressive relapse, integrates mindfulness meditation practices with principles from cognitive therapy [12]. MBCT teaches participants to become more aware of their thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations, observing them without judgment. By cultivating this non-judgmental awareness, individuals can learn to disengage from automatic, habitual thought patterns and emotional reactions, including the intense urges associated with craving [13]. In the context of addiction, MBCT helps individuals respond to triggers and cravings with mindful awareness rather than with an automatic, conditioned response of substance use [14]. This approach provides a practical framework for developing acceptance, self-compassion, and a non-reactive stance toward difficult internal experiences [15].

Schema therapy (ST), developed by Jeffrey Young, is an integrative therapeutic approach that combines elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, attachment theory, and gestalt therapy [16]. ST targets deeply ingrained, pervasive cognitive and emotional patterns, known as early maladaptive schemas, which are believed to originate in childhood due to unmet core needs [17]. These schemas often lead to maladaptive coping styles that manifest in adulthood, particularly in individuals with chronic mental health conditions and substance use disorders [18]. By identifying and modifying these schemas, ST aims to create fundamental and lasting changes in an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, thereby improving emotional regulation, coping skills, and reducing the psychological vulnerabilities that drive substance use [19, 20].

Despite the acknowledged effectiveness of various psychological interventions for stimulant use disorder, a gap remains in the literature regarding a direct comparison of MBCT and ST on key clinical outcomes, such as emotion-focused coping and craving. Both interventions offer unique but potentially complementary mechanisms for change. While ST focuses on addressing core psychological vulnerabilities, MBCT provides a powerful set of skills for present-moment awareness and non-reactivity. The current research is therefore necessary to systematically compare these two distinct but promising therapeutic modalities. The findings will provide valuable insights for clinicians, enabling them to make more informed decisions when selecting an evidence-based intervention. Thus, the primary objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of MBCT and ST on emotion-focused coping strategies and craving in individuals with stimulant use disorder.

Materials and Methods

Design and participants

This clinical trial employed an extensive pre-test, post-test, and follow-up structure to compare the effectiveness of two therapeutic interventions. The statistical population included all individuals with stimulant use disorder who were referred to residential treatment centers in Ahvaz in 2024. From this population, a convenience sample of 45 individuals was selected and randomly assigned to three groups of 15 each: two experimental groups (MBCT and ST) and one control group that received no treatment. Inclusion criteria for participation were a diagnosis of stimulant use disorder based on the DSM-5, an age range of 20 to 45 years, at least basic literacy, and the absence of severe psychiatric illnesses, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Exclusion criteria included missing more than two therapy sessions or experiencing a relapse into substance use during the study period. Before the study commenced, ethical considerations were meticulously followed, including obtaining informed consent from all participants and ensuring the complete confidentiality of their personal information.

Procedure

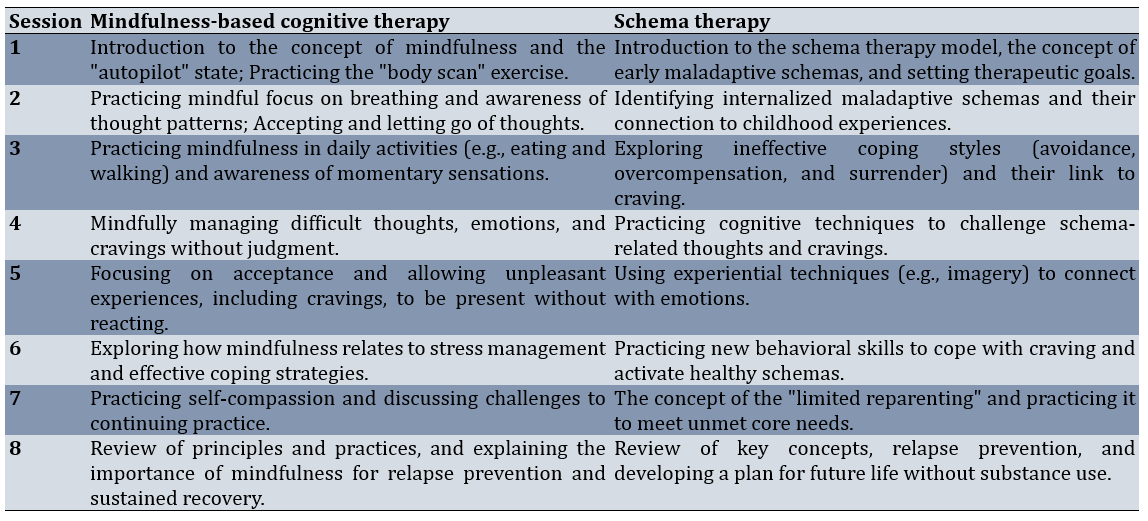

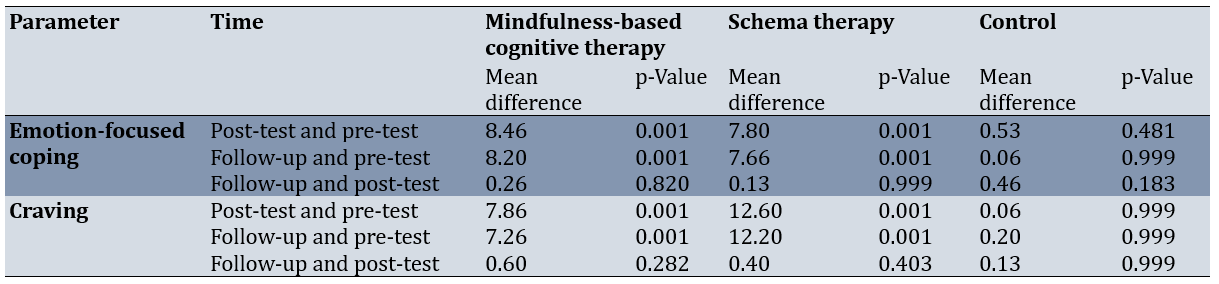

After participants were assigned to their respective groups, a pre-test was administered to all three groups to collect baseline data. The experimental groups (MBCT and ST) then received their respective interventions over eight weekly 90-minute sessions. The control group received no treatment during this period. Following the completion of the sessions, a post-test was administered to all three groups. Finally, follow-up data were collected one month after the intervention concluded (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of schema therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy session content

Research instrument

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ)

This is a widely used instrument for measuring coping strategies, consisting of 66 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0=not at all, 3=a great deal). It assesses two main coping strategies: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. In this study, only the emotion-focused subscale, which contains 40 items, was utilized to measure the dependent parameter. The score range for this subscale is from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating a greater use of emotion-focused strategies [21]. In Persian-language studies, the Cronbach’s alpha for this questionnaire is typically reported to be above 0.85 [22]. In the present study, the overall reliability of the questionnaire was found to be 0.89 using Cronbach’s alpha.

Instantaneous Substance Craving Questionnaire (ISCQ)

This 14-item questionnaire is designed to evaluate the intensity and frequency of craving over a specific time period. The items cover components, such as the intensity of desire, thinking about substance use, and planning to use. Responses are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree), with scores ranging from 14 to 56. Higher scores indicate more severe craving [23]. This tool is widely used in clinical settings due to its brevity and accuracy. In previous studies, the reliability of this questionnaire was reported with a Cronbach’s alpha of approximately 0.90 [24]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this instrument was 0.87, demonstrating its acceptable reliability.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS 26 software to compare the mean scores of the groups across three time points, including pre-test, post-test, and follow-up.

Findings

The study included 45 male participants diagnosed with stimulant use disorder. Their average age was 32.5±6.8 years, ranging from 20 to 45 years. Educational levels varied, with 40% having completed high school, 35% holding a diploma or equivalent qualification, and 25% having obtained higher education degrees. On average, participants had been using stimulants for 5.2±3.1 years and had undergone 1.8±1.2 previous treatment attempts.

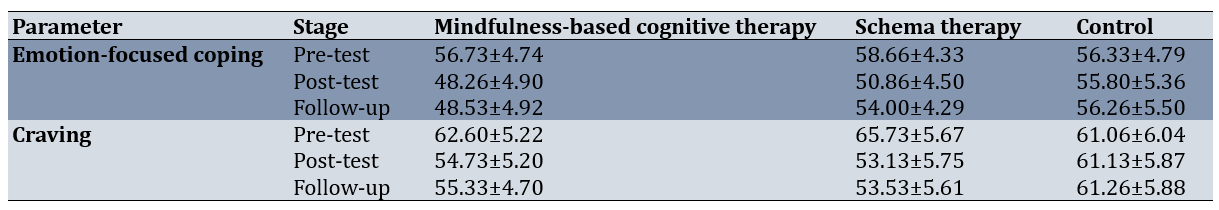

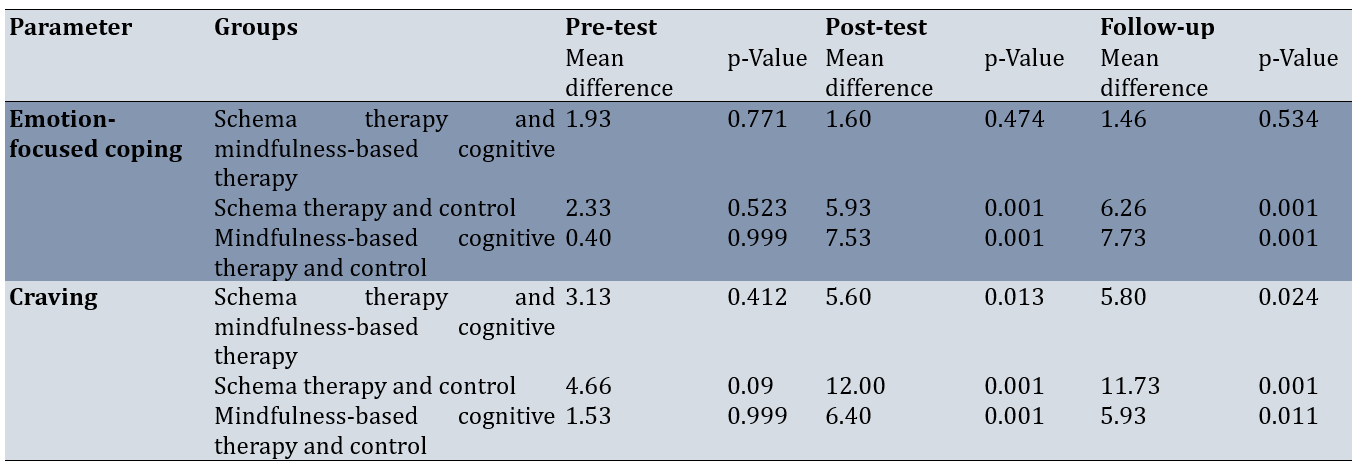

For emotion-focused coping, the MBCT group exhibited a decline from a pre-test to post-test. The ST group showed a reduction from the pre-test to post-test. The control group displayed minimal variation across the three phases. For craving, the MBCT group’s mean decreased from the pre-test to post-test, stabilizing at 55.33±4.70 at follow-up. The ST group demonstrated a more substantial reduction, from pre-test to post-test. The control group’s craving scores remained largely unchanged. These findings suggest that both MBCT and ST effectively reduced both outcomes, with effects sustained at follow-up, whereas the control group showed no notable improvements (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean scores of emotion-focused coping and craving across intervention groups and time points

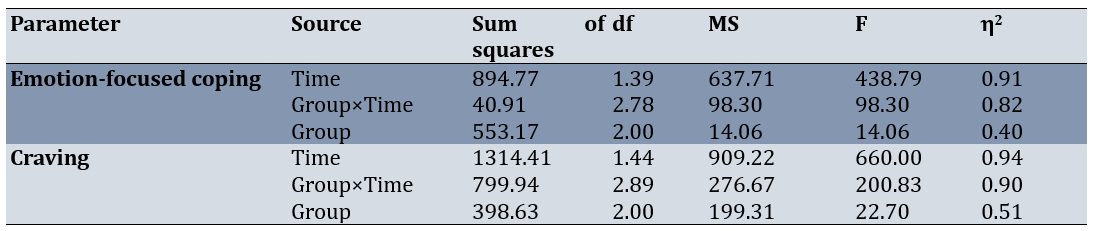

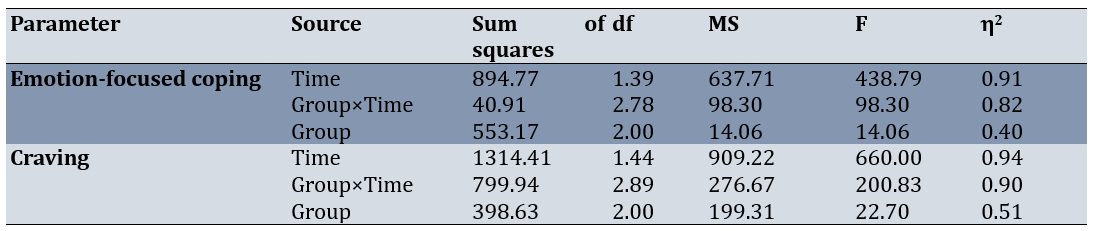

For emotion-focused coping, a significant main effect of time was observed (F=438.79, p<0.001, η²=0.91), indicating substantial changes across the assessment phases. The group-by-time interaction was also significant (F=98.30, p<0.001, η²=0.82), suggesting that the interventions had distinct effects over time. The main effect of group was significant (F=14.06, p<0.001, η²=0.40), highlighting differences across the groups. For craving, a significant main effect of time was found (F=660.00, p<0.001, η²=0.94), along with a significant group-by-time interaction (F=200.83, p<0.001, η²=0.90) and a significant group effect (F=22.70, p<0.001, η²=0.51; Table 3).

Table 3. Repeated measures ANOVA results for emotion-focused coping and craving outcomes (p-Vlaue=0.001)

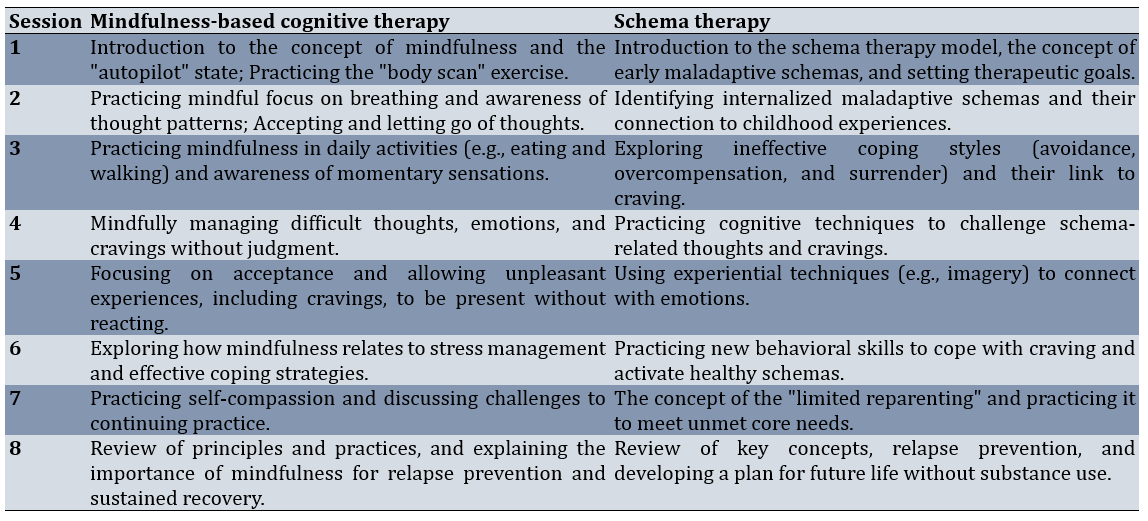

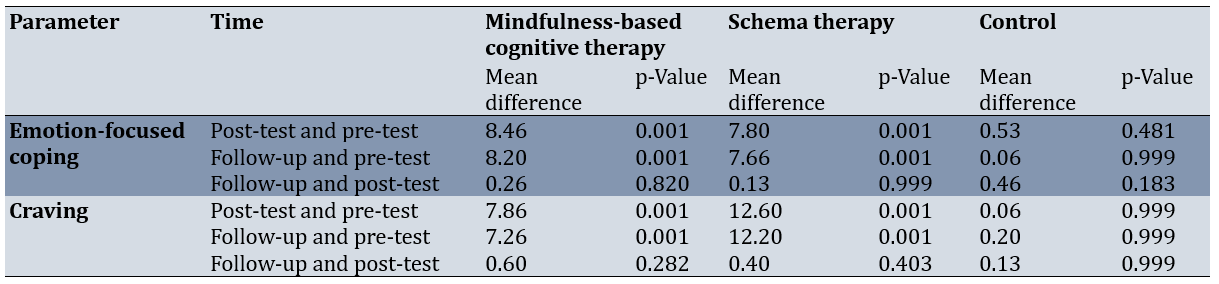

For emotion-focused coping, the MBCT group exhibited significant reductions from pre-test to post-test (p<0.001) and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001), with no significant change between post-test and follow-up (p=0.820). The ST group showed comparable reductions from pre-test to post-test (p<0.001) and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001), with no significant change from post-test to follow-up (p=0.999). The control group showed no significant changes across any phase (p>0.05).

For craving, the MBCT group demonstrated significant reductions from pre-test to post-test (p<0.001) and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001), with no significant change from post-test to follow-up (p=0.282). The ST group exhibited larger reductions from pre-test to post-test (<0.001) and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001), with no significant change between post-test and follow-up (p=0.403). The control group showed no significant changes (p>0.05). Therefore, both interventions produced significant and sustained improvements in emotion-focused coping and craving (Table 4).

Table 4. Within-group comparisons of emotion-focused coping and craving across assessment phases

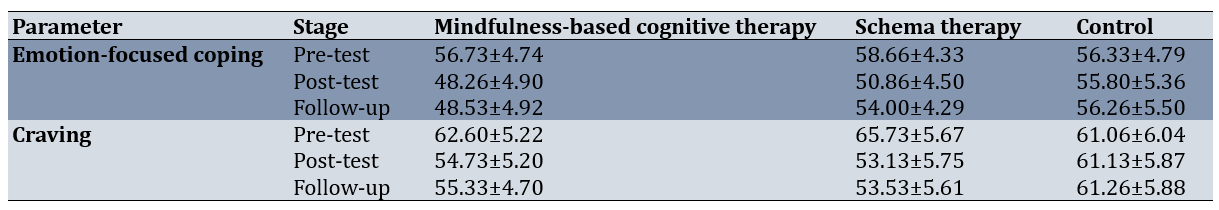

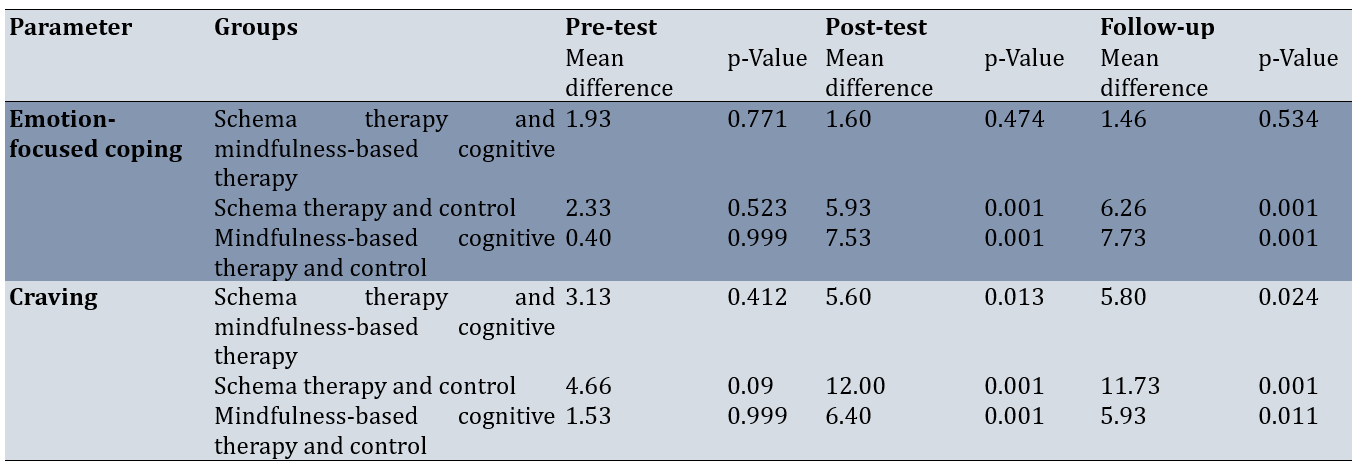

For emotion-focused coping, no significant differences were found between the MBCT and ST groups at pre-test (p=0.771), post-test (p=0.474), or follow-up (p=0.534), indicating similar efficacy. Both intervention groups significantly outperformed the control group at post-test and follow-up. For craving, no significant difference was observed between MBCT and ST at pre-test (p=0.412), but ST showed a statistically significant advantage at post-test (p=0.013) and follow-up (p=0.024). Both interventions significantly reduced craving compared to the control group at post-test and follow-up (Table 5).

Table 5. Between-group comparisons of emotion-focused coping and craving across assessment phases

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of MBCT and ST on emotion-focused coping strategies and craving in individuals with stimulant use disorder. The findings provide robust evidence for the efficacy of both MBCT and ST in addressing two critical dimensions of stimulant use disorder: emotion-focused coping strategies and craving. Both interventions significantly reduced these outcomes compared to the control group, with effects sustained at the one-month follow-up, underscoring their potential as durable, non-pharmacological treatment options. These results align with the hypothesis that targeting maladaptive emotional regulation and craving can disrupt the cycle of addiction, offering valuable insights for clinical practice and future research.

The reduction of emotion-focused coping strategies in the treatment groups aligns with the hypothesis that addiction often serves as a maladaptive strategy for managing difficult emotions. Emotion-focused coping strategies, such as avoidance and denial, typically lead to a temporary suppression of emotional distress rather than a fundamental resolution of the problem, which, in turn, reinforces craving and the risk of relapse [8]. Both interventions effectively helped individuals shift away from these ineffective patterns and confront their emotions in a more adaptive manner. This finding is consistent with prior research showing that mindfulness-based interventions can improve emotional regulation skills and reduce automatic reactions to negative emotions [25, 26]. Specifically, MBCT facilitates the development of non-judgmental awareness, enabling individuals to observe emotional triggers without resorting to maladaptive coping mechanisms. Similarly, ST addresses the underlying schemas that perpetuate these ineffective strategies, fostering healthier emotional processing through cognitive restructuring and experiential techniques. The comparable efficacy of both interventions in reducing emotion-focused coping (with no significant differences between MBCT and ST at post-test or follow-up) suggests that they target overlapping mechanisms of emotional regulation, albeit through distinct therapeutic pathways.

The significant reduction in craving across both experimental groups is a critical finding, given craving’s role as a primary driver of relapse in stimulant use disorder [11]. The observed superiority of ST over MBCT in reducing craving may be attributed to its focus on early maladaptive schemas, which are deeply rooted cognitive and emotional patterns often linked to chronic vulnerabilities in addiction [19, 27]. ST’s integrative approach, combining cognitive, behavioral, and experiential techniques, likely addresses the multifaceted nature of craving, including its emotional and developmental origins. For instance, techniques such as imagery rescripting and limited reparenting may help reframe the emotional triggers that exacerbate craving, offering a more profound restructuring of maladaptive patterns compared to MBCT’s emphasis on present-moment awareness [18, 28]. While MBCT is effective, it primarily targets the immediate experience of craving through mindfulness practices, which may be less intensive in addressing longstanding psychological vulnerabilities [14, 15]. This difference is supported by prior studies, such as Seyedasiaban et al. [28], reporting greater efficacy of ST over mindfulness-based approaches in reducing psychosomatic symptoms in stimulant users.

The sustained effects of both interventions at the one-month follow-up highlight their potential for long-term impact. The lack of significant changes between post-test and follow-up suggests that the skills and insights gained during the eight-week programs were retained, potentially reducing the likelihood of relapse. For MBCT, this durability may stem from the cultivation of mindfulness skills that participants can continue to apply in daily life, fostering resilience against craving and emotional distress [13]. For ST, the focus on modifying core schemas and developing adaptive coping strategies may create lasting changes in how individuals perceive and respond to stressors [20]. These findings are consistent with meta-analyses indicating that both MBCT and ST yield sustained benefits in addiction treatment [14, 19].

From a clinical perspective, these results suggest that both MBCT and ST are viable options for treating stimulant use disorder, with ST potentially offering an advantage for individuals with intense craving driven by deep-seated emotional patterns. Clinicians may consider tailoring treatment based on patient characteristics, such as the presence of personality disorders or trauma, which may align more closely with ST’s schema-focused approach [18]. Conversely, MBCT may be more suitable for individuals seeking practical, skill-based interventions to manage acute craving and stress [15]. The complementary nature of these therapies also raises the possibility of integrating elements of both approaches, such as combining mindfulness practices with schema-focused techniques, to maximize therapeutic outcomes.

Our study underscores the efficacy of MBCT and ST as evidence-based interventions for reducing emotion-focused coping strategies and craving in individuals with stimulant use disorder. The findings contribute to the growing literature on non-pharmacological treatments for addiction, highlighting the potential of both therapies to address core psychological mechanisms of relapse. By offering clinicians evidence to guide treatment selection, this research supports the development of personalized, effective interventions for stimulant use disorder.

This study has some limitations that should be considered when generalizing the results. The relatively small sample size and the use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Additionally, the study focused solely on male participants, and it is recommended that future research include diverse age and gender groups. Further limitations include the short follow-up period of one month, which restricts insights into the long-term efficacy of these interventions, and the lack of assessment of co-occurring mental health conditions, which could influence treatment outcomes [4]. Future studies should employ larger, more diverse samples, extend follow-up durations, and explore the moderating effects of comorbidities. Additionally, investigating the specific mechanisms of change (e.g., schema modification in ST or mindfulness skill acquisition in MBCT) could clarify why ST showed a slight advantage in reducing craving.

While both approaches were equally effective in improving emotion-focused coping strategies, ST showed relative superiority in reducing craving. These results underscore the importance of both therapies as viable non-pharmacological options for managing key symptoms of stimulant use disorder and can inform clinical decision-making.

Conclusion

Both ST and MBCT are effective interventions for reducing emotion-focused coping strategies and craving in individuals with stimulant use disorder.

Acknowledgments: The researchers are grateful to all the individuals who participated in the study.

Ethical Permissions: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch (Reference Number: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.404). Additionally, the research was registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) under the identifier IRCT20250215064733N1.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Choheili H (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Marashian FS (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Safarzadeh S (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Asgari P (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This study did not receive any funding.

Stimulant use disorder, characterized by a pattern of compulsive use of substances such as methamphetamine, cocaine, and prescription stimulants, poses a significant global public health crisis [1]. The prevalence of this disorder is rising, leading to devastating consequences for individuals, families, and communities. From a clinical perspective, individuals with stimulant use disorder often present with a range of severe psychological and behavioral challenges, including a high risk of relapse, cognitive impairment, emotional dysregulation, and social and occupational dysfunction [2, 3]. The chronic nature of the disorder and its high comorbidity with other mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and personality disorders, further complicate treatment and recovery [4]. Effective interventions are therefore urgently needed to address the core mechanisms that perpetuate the cycle of addiction and relapse.

The ability to effectively manage stress and difficult emotional states is a critical determinant of successful recovery from addiction [5]. Coping strategies are the behavioral and psychological efforts individuals use to tolerate, reduce, or minimize stress. Research categorizes these strategies into two primary types, including problem-focused and emotion-focused coping [6]. Problem-focused coping involves actively addressing the source of stress, while emotion-focused coping focuses on regulating the emotional response to stress. In individuals with stimulant use disorder, maladaptive coping patterns, such as avoidance, denial, and wishful thinking, are prevalent and strongly associated with continued substance use and relapse [7, 8]. The over-reliance on emotion-focused coping (which can often be avoidant and passive) is particularly relevant in this population. Therapeutic interventions, therefore, must aim to modify these ineffective emotion-focused strategies.

Craving is an intense desire or urge to use a substance and is recognized as a central feature of stimulant use disorder [9]. It is a powerful predictor of relapse, often triggered by a complex interplay of internal and external cues, including stress, emotional states, and environmental stimuli [10]. Craving is a multifaceted phenomenon with neurobiological, psychological, and behavioral components. From a psychological perspective, craving can be understood as a conditioned response that becomes ingrained through repeated substance use, making it a formidable obstacle to sustained abstinence [11]. Given its direct link to relapse, effective treatment for stimulant use disorder must include strategies specifically designed to manage and reduce the intensity and frequency of craving.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), originally developed to prevent depressive relapse, integrates mindfulness meditation practices with principles from cognitive therapy [12]. MBCT teaches participants to become more aware of their thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations, observing them without judgment. By cultivating this non-judgmental awareness, individuals can learn to disengage from automatic, habitual thought patterns and emotional reactions, including the intense urges associated with craving [13]. In the context of addiction, MBCT helps individuals respond to triggers and cravings with mindful awareness rather than with an automatic, conditioned response of substance use [14]. This approach provides a practical framework for developing acceptance, self-compassion, and a non-reactive stance toward difficult internal experiences [15].

Schema therapy (ST), developed by Jeffrey Young, is an integrative therapeutic approach that combines elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, attachment theory, and gestalt therapy [16]. ST targets deeply ingrained, pervasive cognitive and emotional patterns, known as early maladaptive schemas, which are believed to originate in childhood due to unmet core needs [17]. These schemas often lead to maladaptive coping styles that manifest in adulthood, particularly in individuals with chronic mental health conditions and substance use disorders [18]. By identifying and modifying these schemas, ST aims to create fundamental and lasting changes in an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, thereby improving emotional regulation, coping skills, and reducing the psychological vulnerabilities that drive substance use [19, 20].

Despite the acknowledged effectiveness of various psychological interventions for stimulant use disorder, a gap remains in the literature regarding a direct comparison of MBCT and ST on key clinical outcomes, such as emotion-focused coping and craving. Both interventions offer unique but potentially complementary mechanisms for change. While ST focuses on addressing core psychological vulnerabilities, MBCT provides a powerful set of skills for present-moment awareness and non-reactivity. The current research is therefore necessary to systematically compare these two distinct but promising therapeutic modalities. The findings will provide valuable insights for clinicians, enabling them to make more informed decisions when selecting an evidence-based intervention. Thus, the primary objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of MBCT and ST on emotion-focused coping strategies and craving in individuals with stimulant use disorder.

Materials and Methods

Design and participants

This clinical trial employed an extensive pre-test, post-test, and follow-up structure to compare the effectiveness of two therapeutic interventions. The statistical population included all individuals with stimulant use disorder who were referred to residential treatment centers in Ahvaz in 2024. From this population, a convenience sample of 45 individuals was selected and randomly assigned to three groups of 15 each: two experimental groups (MBCT and ST) and one control group that received no treatment. Inclusion criteria for participation were a diagnosis of stimulant use disorder based on the DSM-5, an age range of 20 to 45 years, at least basic literacy, and the absence of severe psychiatric illnesses, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Exclusion criteria included missing more than two therapy sessions or experiencing a relapse into substance use during the study period. Before the study commenced, ethical considerations were meticulously followed, including obtaining informed consent from all participants and ensuring the complete confidentiality of their personal information.

Procedure

After participants were assigned to their respective groups, a pre-test was administered to all three groups to collect baseline data. The experimental groups (MBCT and ST) then received their respective interventions over eight weekly 90-minute sessions. The control group received no treatment during this period. Following the completion of the sessions, a post-test was administered to all three groups. Finally, follow-up data were collected one month after the intervention concluded (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of schema therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy session content

Research instrument

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ)

This is a widely used instrument for measuring coping strategies, consisting of 66 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0=not at all, 3=a great deal). It assesses two main coping strategies: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. In this study, only the emotion-focused subscale, which contains 40 items, was utilized to measure the dependent parameter. The score range for this subscale is from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating a greater use of emotion-focused strategies [21]. In Persian-language studies, the Cronbach’s alpha for this questionnaire is typically reported to be above 0.85 [22]. In the present study, the overall reliability of the questionnaire was found to be 0.89 using Cronbach’s alpha.

Instantaneous Substance Craving Questionnaire (ISCQ)

This 14-item questionnaire is designed to evaluate the intensity and frequency of craving over a specific time period. The items cover components, such as the intensity of desire, thinking about substance use, and planning to use. Responses are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree), with scores ranging from 14 to 56. Higher scores indicate more severe craving [23]. This tool is widely used in clinical settings due to its brevity and accuracy. In previous studies, the reliability of this questionnaire was reported with a Cronbach’s alpha of approximately 0.90 [24]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this instrument was 0.87, demonstrating its acceptable reliability.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS 26 software to compare the mean scores of the groups across three time points, including pre-test, post-test, and follow-up.

Findings

The study included 45 male participants diagnosed with stimulant use disorder. Their average age was 32.5±6.8 years, ranging from 20 to 45 years. Educational levels varied, with 40% having completed high school, 35% holding a diploma or equivalent qualification, and 25% having obtained higher education degrees. On average, participants had been using stimulants for 5.2±3.1 years and had undergone 1.8±1.2 previous treatment attempts.

For emotion-focused coping, the MBCT group exhibited a decline from a pre-test to post-test. The ST group showed a reduction from the pre-test to post-test. The control group displayed minimal variation across the three phases. For craving, the MBCT group’s mean decreased from the pre-test to post-test, stabilizing at 55.33±4.70 at follow-up. The ST group demonstrated a more substantial reduction, from pre-test to post-test. The control group’s craving scores remained largely unchanged. These findings suggest that both MBCT and ST effectively reduced both outcomes, with effects sustained at follow-up, whereas the control group showed no notable improvements (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean scores of emotion-focused coping and craving across intervention groups and time points

For emotion-focused coping, a significant main effect of time was observed (F=438.79, p<0.001, η²=0.91), indicating substantial changes across the assessment phases. The group-by-time interaction was also significant (F=98.30, p<0.001, η²=0.82), suggesting that the interventions had distinct effects over time. The main effect of group was significant (F=14.06, p<0.001, η²=0.40), highlighting differences across the groups. For craving, a significant main effect of time was found (F=660.00, p<0.001, η²=0.94), along with a significant group-by-time interaction (F=200.83, p<0.001, η²=0.90) and a significant group effect (F=22.70, p<0.001, η²=0.51; Table 3).

Table 3. Repeated measures ANOVA results for emotion-focused coping and craving outcomes (p-Vlaue=0.001)

For emotion-focused coping, the MBCT group exhibited significant reductions from pre-test to post-test (p<0.001) and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001), with no significant change between post-test and follow-up (p=0.820). The ST group showed comparable reductions from pre-test to post-test (p<0.001) and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001), with no significant change from post-test to follow-up (p=0.999). The control group showed no significant changes across any phase (p>0.05).

For craving, the MBCT group demonstrated significant reductions from pre-test to post-test (p<0.001) and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001), with no significant change from post-test to follow-up (p=0.282). The ST group exhibited larger reductions from pre-test to post-test (<0.001) and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001), with no significant change between post-test and follow-up (p=0.403). The control group showed no significant changes (p>0.05). Therefore, both interventions produced significant and sustained improvements in emotion-focused coping and craving (Table 4).

Table 4. Within-group comparisons of emotion-focused coping and craving across assessment phases

For emotion-focused coping, no significant differences were found between the MBCT and ST groups at pre-test (p=0.771), post-test (p=0.474), or follow-up (p=0.534), indicating similar efficacy. Both intervention groups significantly outperformed the control group at post-test and follow-up. For craving, no significant difference was observed between MBCT and ST at pre-test (p=0.412), but ST showed a statistically significant advantage at post-test (p=0.013) and follow-up (p=0.024). Both interventions significantly reduced craving compared to the control group at post-test and follow-up (Table 5).

Table 5. Between-group comparisons of emotion-focused coping and craving across assessment phases

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of MBCT and ST on emotion-focused coping strategies and craving in individuals with stimulant use disorder. The findings provide robust evidence for the efficacy of both MBCT and ST in addressing two critical dimensions of stimulant use disorder: emotion-focused coping strategies and craving. Both interventions significantly reduced these outcomes compared to the control group, with effects sustained at the one-month follow-up, underscoring their potential as durable, non-pharmacological treatment options. These results align with the hypothesis that targeting maladaptive emotional regulation and craving can disrupt the cycle of addiction, offering valuable insights for clinical practice and future research.

The reduction of emotion-focused coping strategies in the treatment groups aligns with the hypothesis that addiction often serves as a maladaptive strategy for managing difficult emotions. Emotion-focused coping strategies, such as avoidance and denial, typically lead to a temporary suppression of emotional distress rather than a fundamental resolution of the problem, which, in turn, reinforces craving and the risk of relapse [8]. Both interventions effectively helped individuals shift away from these ineffective patterns and confront their emotions in a more adaptive manner. This finding is consistent with prior research showing that mindfulness-based interventions can improve emotional regulation skills and reduce automatic reactions to negative emotions [25, 26]. Specifically, MBCT facilitates the development of non-judgmental awareness, enabling individuals to observe emotional triggers without resorting to maladaptive coping mechanisms. Similarly, ST addresses the underlying schemas that perpetuate these ineffective strategies, fostering healthier emotional processing through cognitive restructuring and experiential techniques. The comparable efficacy of both interventions in reducing emotion-focused coping (with no significant differences between MBCT and ST at post-test or follow-up) suggests that they target overlapping mechanisms of emotional regulation, albeit through distinct therapeutic pathways.

The significant reduction in craving across both experimental groups is a critical finding, given craving’s role as a primary driver of relapse in stimulant use disorder [11]. The observed superiority of ST over MBCT in reducing craving may be attributed to its focus on early maladaptive schemas, which are deeply rooted cognitive and emotional patterns often linked to chronic vulnerabilities in addiction [19, 27]. ST’s integrative approach, combining cognitive, behavioral, and experiential techniques, likely addresses the multifaceted nature of craving, including its emotional and developmental origins. For instance, techniques such as imagery rescripting and limited reparenting may help reframe the emotional triggers that exacerbate craving, offering a more profound restructuring of maladaptive patterns compared to MBCT’s emphasis on present-moment awareness [18, 28]. While MBCT is effective, it primarily targets the immediate experience of craving through mindfulness practices, which may be less intensive in addressing longstanding psychological vulnerabilities [14, 15]. This difference is supported by prior studies, such as Seyedasiaban et al. [28], reporting greater efficacy of ST over mindfulness-based approaches in reducing psychosomatic symptoms in stimulant users.

The sustained effects of both interventions at the one-month follow-up highlight their potential for long-term impact. The lack of significant changes between post-test and follow-up suggests that the skills and insights gained during the eight-week programs were retained, potentially reducing the likelihood of relapse. For MBCT, this durability may stem from the cultivation of mindfulness skills that participants can continue to apply in daily life, fostering resilience against craving and emotional distress [13]. For ST, the focus on modifying core schemas and developing adaptive coping strategies may create lasting changes in how individuals perceive and respond to stressors [20]. These findings are consistent with meta-analyses indicating that both MBCT and ST yield sustained benefits in addiction treatment [14, 19].

From a clinical perspective, these results suggest that both MBCT and ST are viable options for treating stimulant use disorder, with ST potentially offering an advantage for individuals with intense craving driven by deep-seated emotional patterns. Clinicians may consider tailoring treatment based on patient characteristics, such as the presence of personality disorders or trauma, which may align more closely with ST’s schema-focused approach [18]. Conversely, MBCT may be more suitable for individuals seeking practical, skill-based interventions to manage acute craving and stress [15]. The complementary nature of these therapies also raises the possibility of integrating elements of both approaches, such as combining mindfulness practices with schema-focused techniques, to maximize therapeutic outcomes.

Our study underscores the efficacy of MBCT and ST as evidence-based interventions for reducing emotion-focused coping strategies and craving in individuals with stimulant use disorder. The findings contribute to the growing literature on non-pharmacological treatments for addiction, highlighting the potential of both therapies to address core psychological mechanisms of relapse. By offering clinicians evidence to guide treatment selection, this research supports the development of personalized, effective interventions for stimulant use disorder.

This study has some limitations that should be considered when generalizing the results. The relatively small sample size and the use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Additionally, the study focused solely on male participants, and it is recommended that future research include diverse age and gender groups. Further limitations include the short follow-up period of one month, which restricts insights into the long-term efficacy of these interventions, and the lack of assessment of co-occurring mental health conditions, which could influence treatment outcomes [4]. Future studies should employ larger, more diverse samples, extend follow-up durations, and explore the moderating effects of comorbidities. Additionally, investigating the specific mechanisms of change (e.g., schema modification in ST or mindfulness skill acquisition in MBCT) could clarify why ST showed a slight advantage in reducing craving.

While both approaches were equally effective in improving emotion-focused coping strategies, ST showed relative superiority in reducing craving. These results underscore the importance of both therapies as viable non-pharmacological options for managing key symptoms of stimulant use disorder and can inform clinical decision-making.

Conclusion

Both ST and MBCT are effective interventions for reducing emotion-focused coping strategies and craving in individuals with stimulant use disorder.

Acknowledgments: The researchers are grateful to all the individuals who participated in the study.

Ethical Permissions: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch (Reference Number: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.404). Additionally, the research was registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) under the identifier IRCT20250215064733N1.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Choheili H (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Marashian FS (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Safarzadeh S (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Asgari P (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This study did not receive any funding.

Keywords:

References

1. Hankins D. Stimulant use disorders. In: Avery J, Makovkina E, editors. Substance use disorders and behavioral addictions: A comprehensive guide. Cham: Springer; 2025. p. 1-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-57159-6_63-1]

2. Ramey T, Regier PS. Cognitive impairment in substance use disorders. CNS Spectr. 2019;24(1):102-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1092852918001426]

3. London ED, Groman SM, Leyton M, De Wit H. The mesocorticolimbic system in stimulant use disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2025;1. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41380-025-03148-0]

4. Iqbal MN, Levin CJ, Levin FR. Treatment for substance use disorder with co-occurring mental illness. Focus. 2019;17(2):88-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1176/appi.focus.20180042]

5. Volkow ND, Blanco C. Substance use disorders: A comprehensive update of classification, epidemiology, neurobiology, clinical aspects, treatment and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2023;22(2):203-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/wps.21073]

6. Guadalupe C, DeShong HL. Personality and coping: A systematic review of recent literature. Personal Individ Differ. 2025;239:113119. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2025.113119]

7. Carlon HA, Peters G, Villarosa-Hurlocker MC. When stimulant use becomes problematic: Examining the role of coping styles. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(3):442-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10826084.2021.2019774]

8. Van Der Heijden HS, Schirmbeck F, Berry L, Simons CJP, Bartels-Velthuis AA, Bruggeman R, et al. Impact of coping styles on substance use in persons with psychosis, siblings, and controls. Schizophr Res. 2022;241:102-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2022.01.030]

9. Salem BA, Gonzales-Castaneda R, Ang A, Rawson RA, Dickerson D, Chudzynski J, et al. Craving among individuals with stimulant use disorder in residential social model-based treatment-Can exercise help?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109247. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109247]

10. Cless MM, Courchesne-Krak NS, Bhatt KV, Mittal ML, Marienfeld CB. Craving among patients seeking treatment for substance use disorder. Discov Ment Health. 2023;3(1):23. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s44192-023-00049-y]

11. Baillet E, Auriacombe M, Romao C, Garnier H, Gauld C, Vacher C, et al. Craving changes in first 14 days of addiction treatment: An outcome predictor of 5 years substance use status?. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14(1):497. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41398-024-03193-3]

12. Musa ZA, Kim Lam S, Binti Mamat Mukhtar F, Kwong Yan S, Tajudeen Olalekan O, Kim Geok S. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on the management of depressive disorder: Systematic review. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2020;12:100200. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100200]

13. Biniyaz H, Shahabizadeh F. Effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and intellectual-motor exercises in craving beliefs among industrial substance abusers. J Res Health. 2019;9(2):169-80. [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jrh.9.2.169]

14. Demina A, Petit B, Meille V, Trojak B. Mindfulness interventions for craving reduction in substance use disorders and behavioral addictions: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Neurosci. 2023;24(1):55. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12868-023-00821-4]

15. Melero Ventola AR, Yela JR, Crego A, Cortés-Rodríguez M. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy group intervention in reducing gambling-related craving. J Evid Based Psychother. 2020;20(1):107-34. [Link] [DOI:10.24193/jebp.2020.1.7]

16. Pilkington PD, Younan R, Karantzas GC. Identifying the research priorities for schema therapy: A Delphi consensus study. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2023;30(2):344-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2800]

17. Uvelli A, Floridi M, Agrusti G, Franquillo AC, Fiumalbi L, Micheloni T, et al. When adverse experiences influence the interpretation of ourselves, others and the world: A systematic review and meta-analysis of maladaptive schemas in victims of violence. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2025;32(4):e70114. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cpp.70114]

18. Talbot D, Harvey L, Cohn V, Truscott M. Combatting comorbidity: The promise of schema therapy in substance use disorder treatment. Discov Psychol. 2024;4(1):64. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s44202-024-00179-6]

19. Lacy E. STAT: Schema therapy for addiction treatment, a proposal for the integrative treatment of addictive disorders. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1366617. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1366617]

20. Pourpashang M, Mousavi S. The effects of group schema therapy on psychological wellbeing and resilience in the clients under substance dependence treatment. J Client Cent Nurs Care. 2021;7(2):159-66. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.7.2.366.1]

21. Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Ways of coping questionnaire (WAYS). Database record. Washington, DC: APA PsycTests; 1988. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/t06501-000]

22. Taherkhani S. The factor structure of the ways of coping questionnaire among abused Iranian women. J Adult Prot. 2023;25(1):33-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/JAP-07-2022-0015]

23. Franken IH, Hendriksa VM, Van Den Brink W. Initial validation of two opiate craving questionnaires the obsessive compulsive drug use scale and the desires for drug questionnaire. Addict Behav. 2002;27(5):675-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00201-5]

24. Amiri H, Makvandi B, Askari P, Naderi F, Ehteshamzadeh P. The effectiveness of matrix interventions in reducing the difficulty in cognitive emotion regulation and craving in methamphetamine-dependent patients. Shahroud J Med Sci. 2019;5(4). [Link]

25. Najafi Chaleshtori M, Asgari P, Heidari A, Dasht Bozorgi Z, Hafezi F. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention in distress tolerance and sensation-seeking in adolescents with a drug-addicted parent. J Res Health. 2022;12(5):355-62. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JRH.12.5.1889.2]

26. Kebriti H, Zanjani Z, Omidi A, Sayyah M. Effect of mindfulness-based stress management therapy on emotion regulation, anxiety, depression, and food addiction in obese people: A randomized clinical trial. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2023;33(224):28-38. [Persian] [Link]

27. Naseri E. Efficacy of dual focus schema therapy in the treatment of people with substance use disorders comorbid with personality disorders. Clin Psychol Stud. 2020;11(41):43-65. [Persian] [Link]

28. SeyedAsiaban S, Manshaee GR, Askari P. Compare the effectiveness of schema therapy and mindfulness on psychosomatic symptoms in people with substance abuse stimulants. Res Addctn. 2017;10(40):181-99. [Persian] [Link]