Volume 6, Issue 4 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(4): 185-202 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2025/08/12 | Accepted: 2025/09/28 | Published: 2025/10/3

Received: 2025/08/12 | Accepted: 2025/09/28 | Published: 2025/10/3

How to cite this article

Zarshenas L, Mehri Z, Rakhshan M, Khademian Z, Mehrabi M, Jamshidi Z. A Systematic Review and Nursing Organizations Guidelines on Professional Competence Standards for Nurses. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (4) :185-202

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-442-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-442-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

2- Student Research Committee, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

3- “Community Based Psychiatric Care Research Center” and “School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

4- Department of e-Learning in Medical Sciences, Virtual School, Center of Excellence for e-Learning in Medical Sciences, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

2- Student Research Committee, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

3- “Community Based Psychiatric Care Research Center” and “School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

4- Department of e-Learning in Medical Sciences, Virtual School, Center of Excellence for e-Learning in Medical Sciences, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (12 Views)

Introduction

Nurses make up a large proportion of the health workforce in many countries worldwide, and through the provision of services and basic care, they are a key component of healthcare systems [1]. The increasing role of nurses in healthcare has led to a growing need for them to fulfill a variety of roles [2]. This creates a high demand for nurses to work in various healthcare settings, including hospitals, public and private health centers, primary care centers, nursing homes, ambulatory surgery centers, schools, psychiatric centers, the military, industrial centers, healthcare research centers, universities, home care centers, and insurance companies [3]. As providers of comprehensive care to patients, nurses are expected to act in accordance with their professional responsibilities when caring for individuals [4]. In this regard, it should be noted that the improvement of healthcare quality is directly linked to the professional competence of nurses [5].

Professional competence has many dimensions and is influenced by a variety of factors [6]. It is one of the dimensions of competence and is an important and fundamental concept in the field of nursing [5]. The concept of professional competence is complex, multi-layered, and contextual [7]. To date, different dimensions of competence in nursing have been introduced; in this respect, the following can be mentioned: professional competence, interdisciplinary competence, clinical competence, individual competence, research competence, educational competence, and cultural competence [6]. Professional competence is considered a continuum that may increase or decrease over time, depending on various factors [8]. Improving the competencies of nurses across these dimensions will lead to various achievements, including the professional socialization and professionalization of nurses, as well as the provision of high-quality services to patients [4, 9, 10].

Different country-specific definitions of competence have been provided, depending on the context of each country [11]. This has resulted in ambiguity and complexity regarding the concept, as well as the absence of a uniform definition of competence [12, 13]. The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines competence as having sufficient knowledge, skills, judgment, and ability to carry out a particular task or function [13]. Gunawan and Aungsuroch refer to competence as a set of knowledge, attitudes, and skills that are manifested through behavior [14]. According to Fukada, competence is a behavioral trait and an acquisition of skills that results from experience and learning. It is achieved by the individual based on their attitudes and motivations, and by utilizing their individual interests and experiences [4]. DeGrande et al. define professional competence as the ability to make clinical decisions in accordance with clinical circumstances and based on prior experience [15].

Numerous studies show that there are significant differences and discrepancies in the implementation of standards and dimensions of nurse competencies, as well as the factors that influence them. Halcomb et al. listed clinical performance, professionalism, communication, and improving patient health as standards of competence for nurses [16]. According to the study by Valizadeh et al., the concept of competence is based on knowledge, attitude, skills, motivation, experience, creativity, responsibility, holistic care, ethical action, clinical judgment, communication with patients, cooperation and teamwork, management and leadership, perseverance and stability, and the ability to cope with difficult and complex situations [7]. In the study by DeGrande et al., the main dimensions of a nurse’s competence are described as situation management, teamwork, and decision-making [15]. In the study conducted by Smith, the integration of knowledge and practice, critical thinking, motivation, experience, skill, environment, communication, and professionalism are introduced :as char:acteristics of nurse competence [17].

In the existing literature, various factors have been identified as influencing the development of nurses’ professional competencies and the support they receive. The competence of nurses is affected by several factors, such as individual characteristics, educational level, work experience, professionalism, the type of environment in which they work, and critical thinking [18]. Tabari Khomeiran et al. report individual characteristics, motivation, theoretical knowledge, opportunities, experience, and environment as personal and non-personal factors that influence the development of nurses’ professional competencies [8]. In a study by Gunawan et al., age, marital status, educational level, specialized knowledge, clinical experience, job satisfaction, employment status, job position, income, burnout, and continuing education are identified as factors influencing clinical competence in nurses [11]. Nehrir et al. report other factors, such as knowledge, personal experiences, professional skills, motivation, decision-making power, self-confidence, professional independence, and positive social interactions as factors affecting nurses’ competence [6].

Nurses face a number of professional competency needs during their careers [19]. If these needs are not addressed and met, many nurses will leave the profession [19]; if these nurses are retained in the health system, the quality of care will deteriorate, and public health will be compromised [5]. Therefore, it appears necessary to focus on the standards of professional competence for nurses. Different standards have been implemented in various organizations; however, given the context-dependent nature of standards of professional competence, a systematic review is needed. This is because no comprehensive study has been found that reviews these standards based on existing literature, scientific articles, and the guidelines of national and international nursing organizations. Consequently, we decided to conduct a systematic review of the literature and nursing organizations’ guidelines to determine the competence standards for nurses. The results are expected to further develop the professional competencies of nurses, improve the quality of care, increase patient satisfaction, and promote the health of individuals in society.

Information and Methods

This systematic review of nursing professional competence standards was conducted based on the available scientific literature in Iran and worldwide, with the aim of reviewing the standards of nursing professional competence in 2023. Databases, such as the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and the Cochrane Library were consulted to determine the standards of competence for nurses and to confirm that the study was not duplicative [20].

Guidance, such as the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement is used in the preparation of the study protocol [20, 21]. Following the development of the protocol, the standards were reviewed based on the PRISMA 2020 statement to identify the standards of competence for nurses.

To ensure that the articles are fully covered, simultaneous searches of the databases PubMed, MEDLINE, and Embase are required [22, 23]. Researchers examined external databases, such as PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane, ProQuest, and the Web of Science. Google Scholar was also reviewed to ensure that the search is comprehensive. Additionally, internal databases, such as SID, IranMedex, IranDoc, and Magiran were searched.

A national nursing organization is a professional entity that coordinates, exchanges ideas, promotes, stimulates, educates, researches, and organizes scientific activities while providing human resources through policy development, legislation, and standardization. The International Council of Nurses is a large, global organization of nurses that influences nursing practice by setting standards and communicating procedures [24].

The keywords were selected from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), synonyms in various databases, and related free terms by two researchers. Studies on the competence of nurses were also examined to identify keywords relevant to this issue [20, 25].

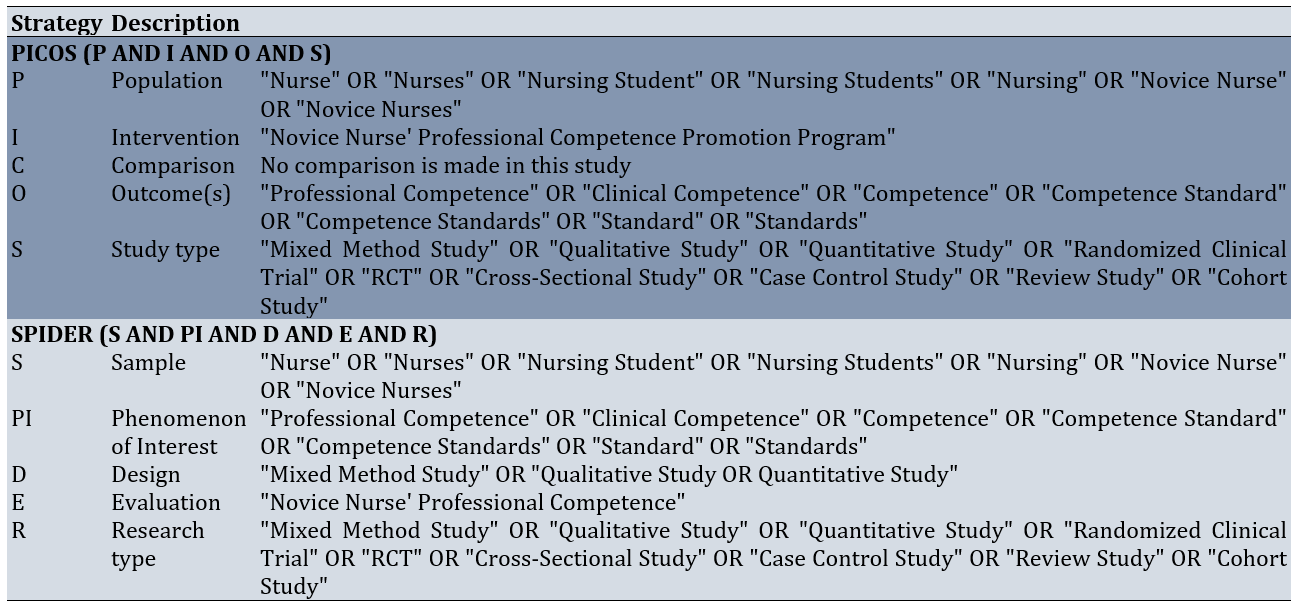

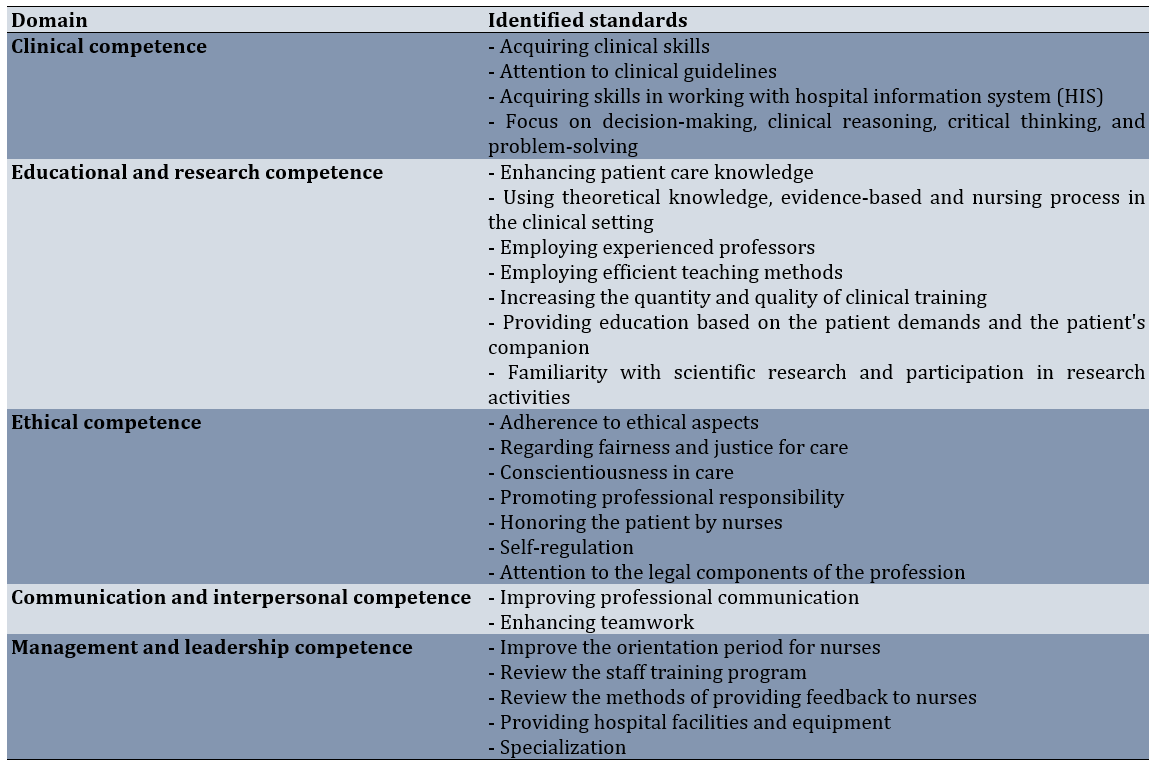

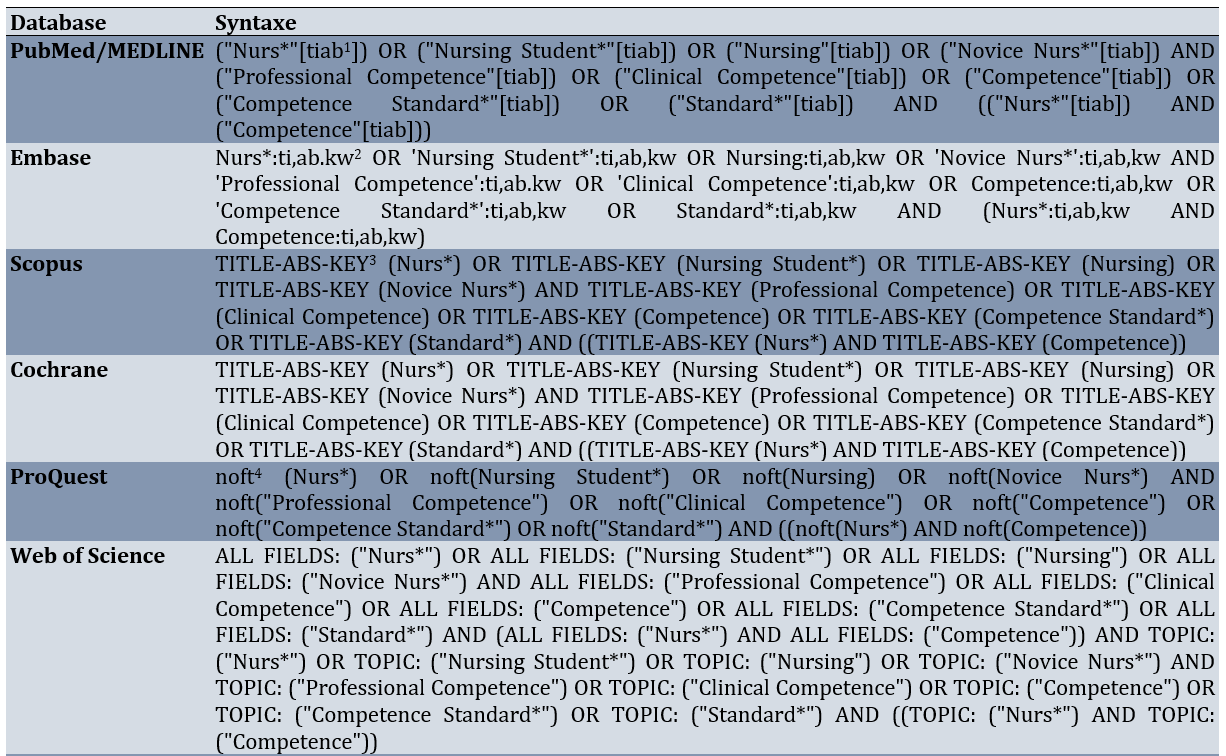

Searches were performed in the title, abstract, and keywords in foreign databases using Population or Problem, Intervention or Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design (PICOS) and Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research Type (SPIDER) [26]. Additionally, the search was also conducted in Persian databases using translations of the aforementioned keywords in Persian and the same search strategy (Table 1).

Table 1. Review of professional competence standards for nurses using PICOS and SPIDER search strategies

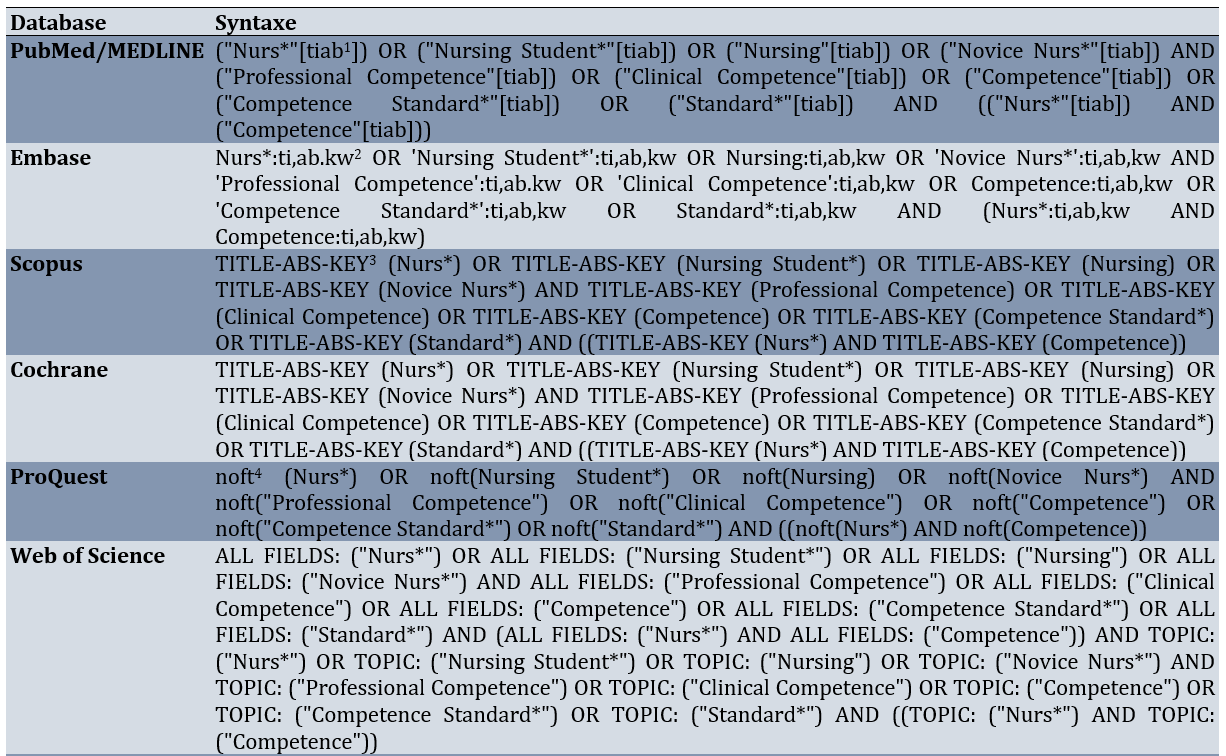

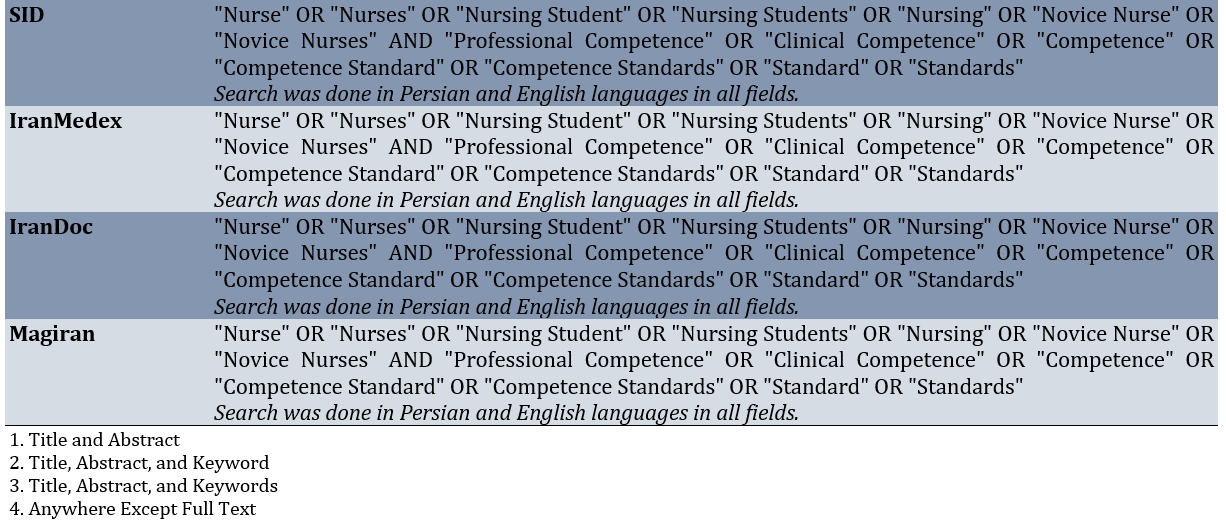

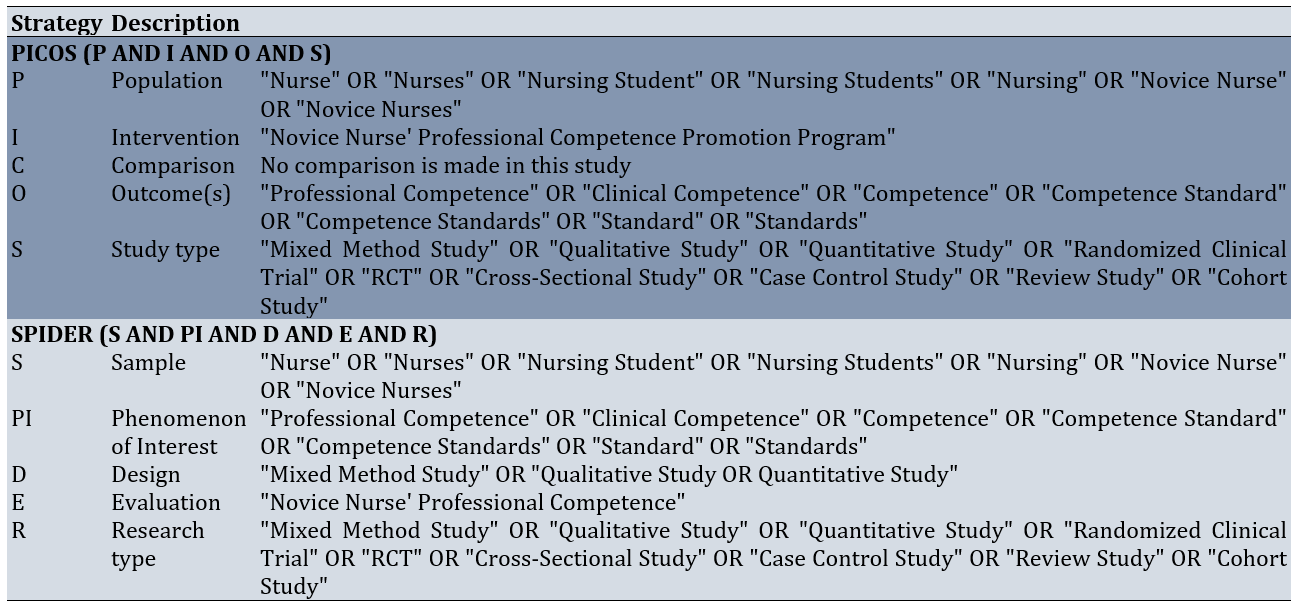

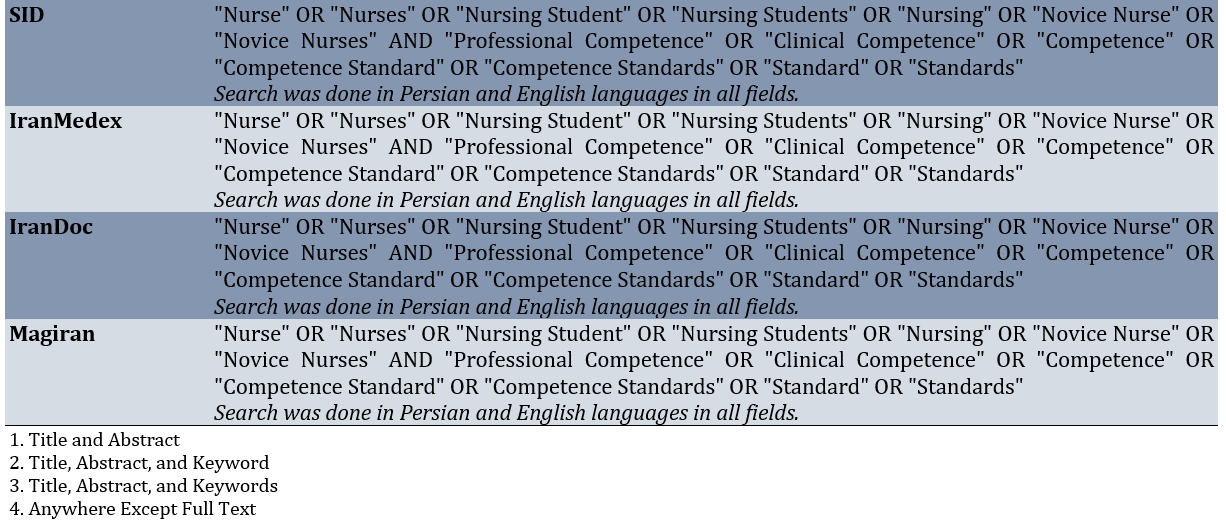

Syntaxes were

developed and utilized to search both Iranian and foreign databases comprehensively and accurately, based on search strategies specific to each database (Table 2).

Table 2. Internal and external database syntaxes

The inclusion criteria were Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method articles that contain at least one of the professional competence standards for nurses in the title, keywords, or abstract of the article, scientific articles that have been published in peer-reviewed journals, articles from Iranian and foreign conferences that include at least one of the professional competence standards for nurses in the title, keywords, or abstract, guidelines and reports from reputable Iranian and international nursing organizations that feature at least one of the professional competence standards for nurses, and scientific articles, conference papers, guidelines, and reports that are relevant to the research question. Since the oldest article mentioning the competence standards for nurses was Davey’s article in 1995 [27], studies published from 1995 onwards were included in the study. A study was excluded if there was a lack of access to the full article due to unresolved journal access constraints.

The search results were compiled into a comprehensive list of articles, guidelines, and reports related to the research question. For better management of the results, references were stored in Mendeley Reference Management Software (version 1.19.8, 2008-2020, Mendeley Ltd) to facilitate the identification and removal of duplicate articles, guidelines, and reports [20].

After managing the search results and removing duplicate sources, the results were screened to identify resources related to the research question that met the inclusion criteria for studies. Accordingly, the titles and abstracts were first reviewed by two researchers, and in cases of disagreement, a third researcher was consulted. The screening occurred in two stages. First, sources were screened and briefly reviewed to identify potentially relevant materials. The full text of these potentially relevant sources was downloaded and printed before the complete study of the sources was conducted and the selection of those meeting the inclusion criteria was finalized. Following the screening, sources were selected to help establish the standards of professional competence for nurses [20].

The quality of quantitative articles was assessed using the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) checklist, qualitative articles were assessed with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist, and mixed-method articles were evaluated using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) [28-30].

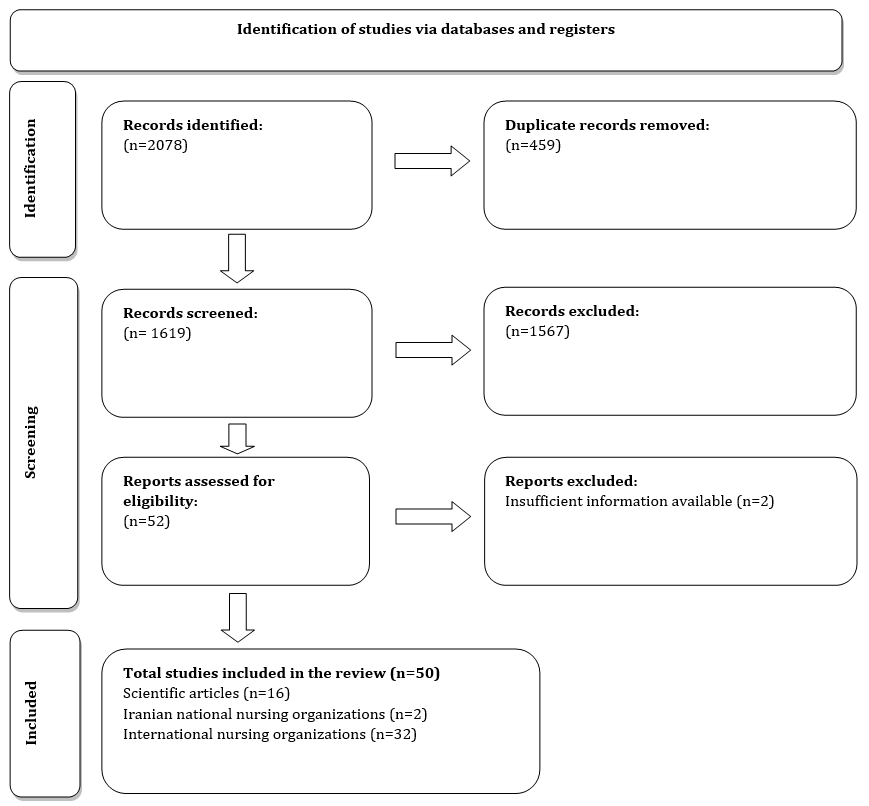

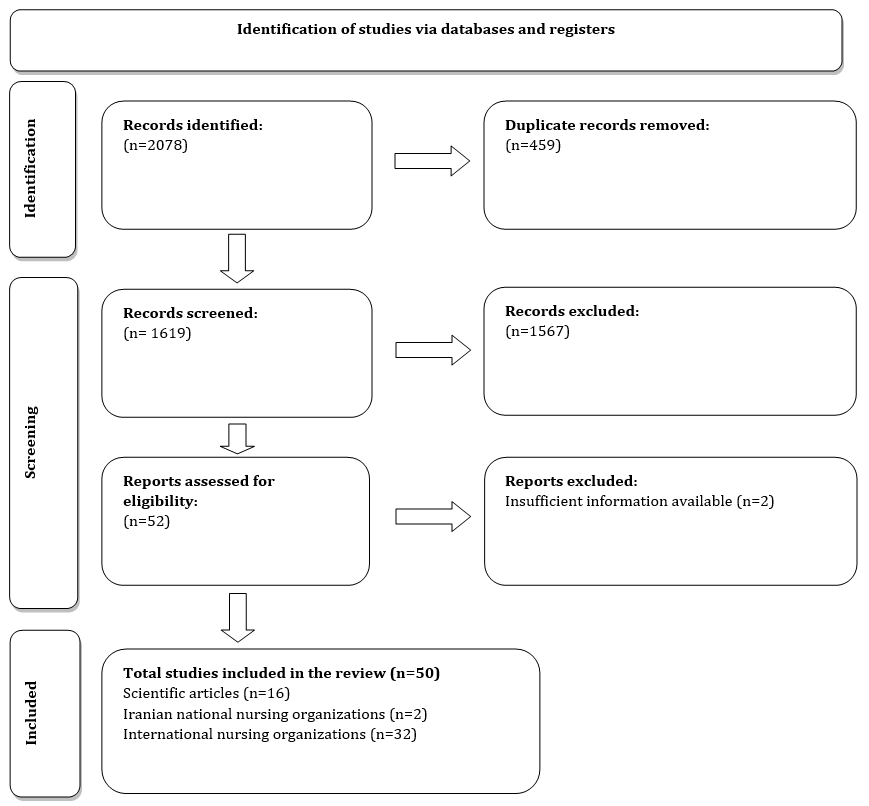

A list of characteristics of the sources and the number of imported and exported resources was prepared to facilitate future revisions [20]. In this regard, a flowchart was developed based on the PRISMA 2020 statement to illustrate the number of imported and exported resources [28].

After screening the search results, a data extraction process was carried out. The researcher accomplished this by creating a table for data extraction [20]. The data extraction table for the articles contained the title of the study, the purpose, the authors, the year of publication, the location of the study, the data collection methods and tools, the study sample, and the results related to the proficiency standards for nurses. Additionally, given the type of available data on Iranian and international nursing organizations, the proposed form included information, such as the name of the organization, the year of publication, and the results concerning the standards of nursing competence.

The obtained findings were pooled after data extraction [20]. In this regard, a data extraction table was completed for each resource. Then, the tables were set up in Microsoft Word Professional Plus 2016 (16.0.17126.20132). Each of the extracted resources, which had been entered in the aggregated forms, was then recorded in one form for scientific articles and another form for nursing organizations. After categorizing the extracted information, the standards of competence for nurses were determined.

Findings

A total of 2,078 documents were initially received from scientific articles and from Iranian and international nursing organizations. After removing duplicate documents using Mendeley software, 1,619 documents remained. The researchers selected 52 documents relevant to the study objectives by examining the remaining documents and abstracts. Due to the lack of full text for two articles, the systematic review of the standards of competence for nurses ultimately covered 50 eligible documents, including 16 articles, 2 national nursing organizations, and 32 international nursing organizations (Figure 1) [31].

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews, which included searches of databases and registers only.

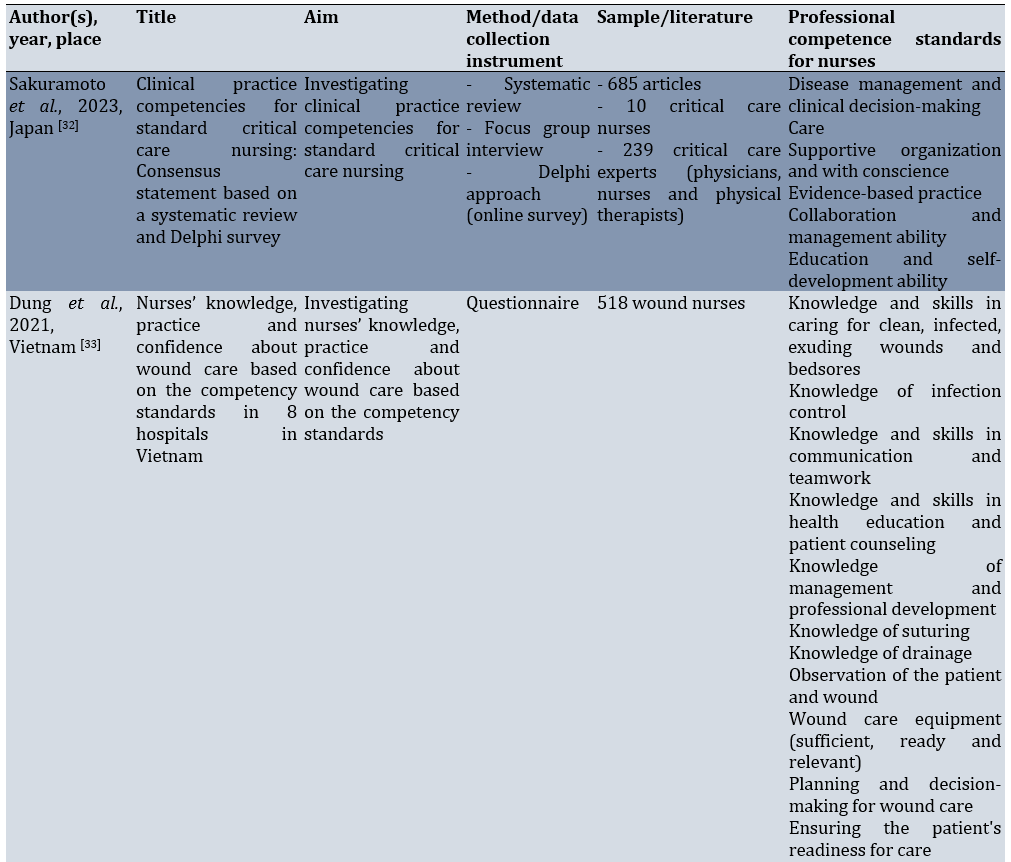

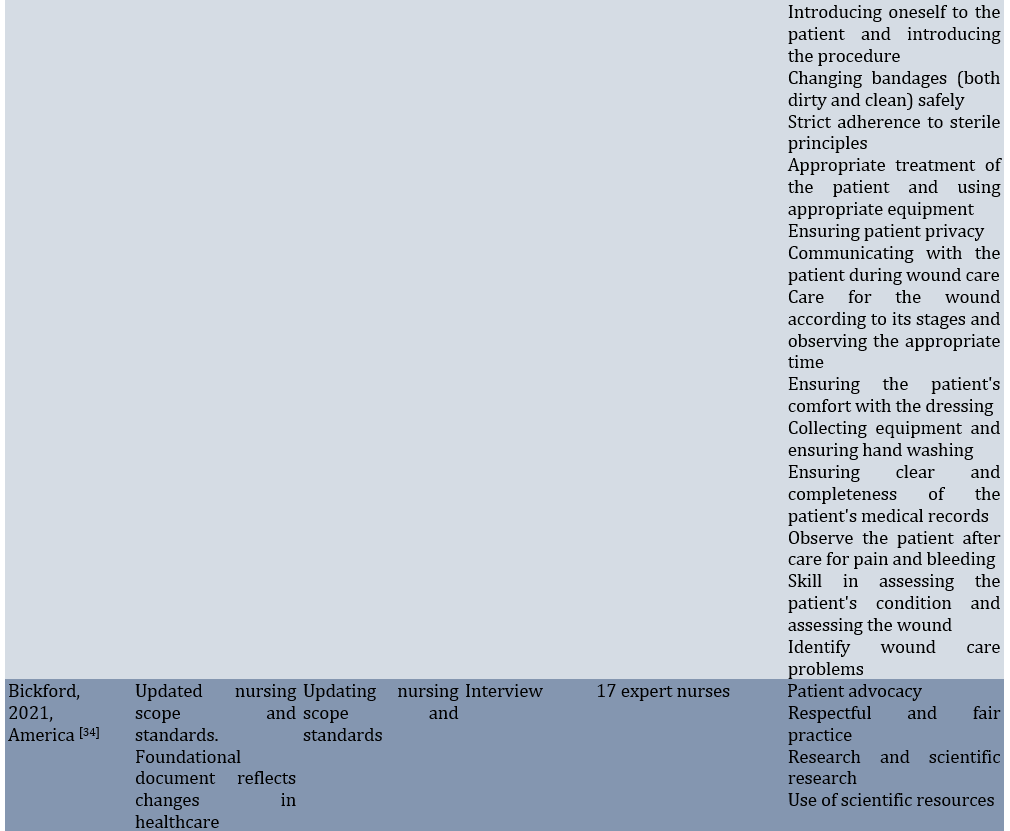

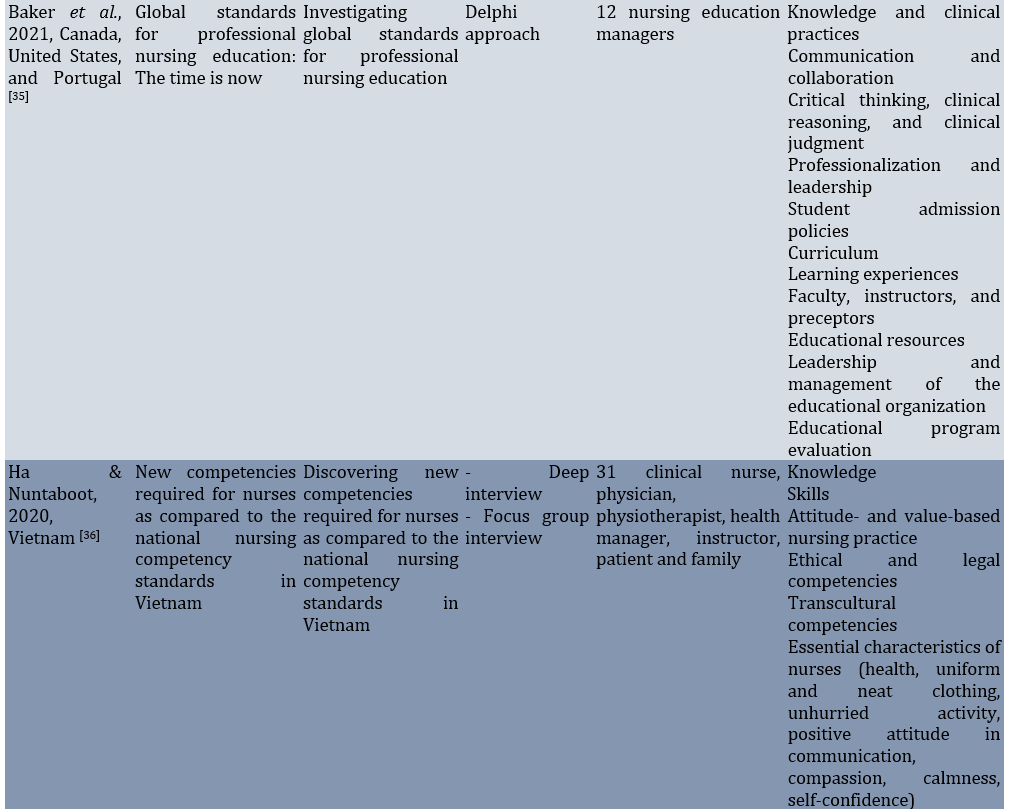

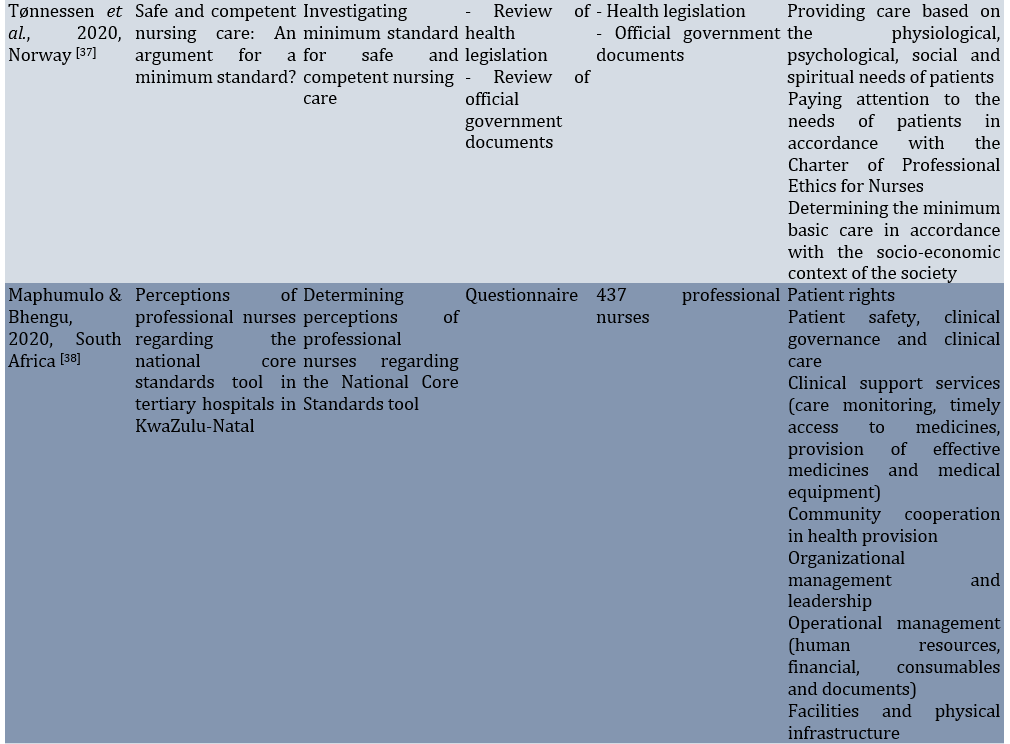

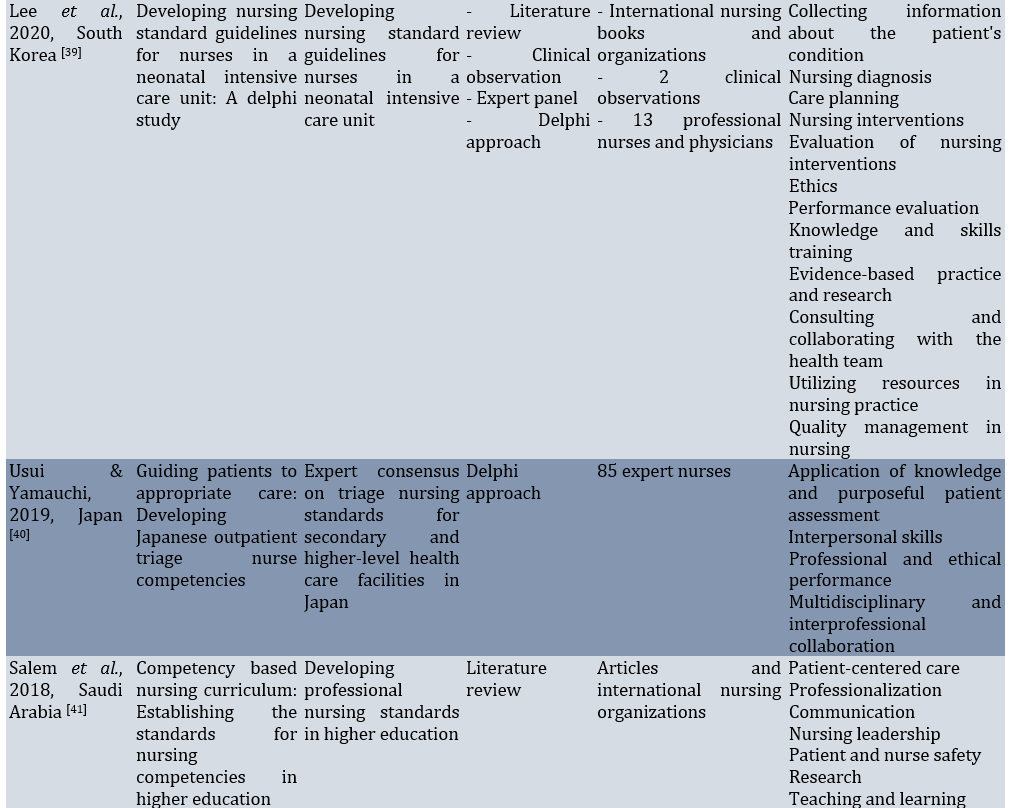

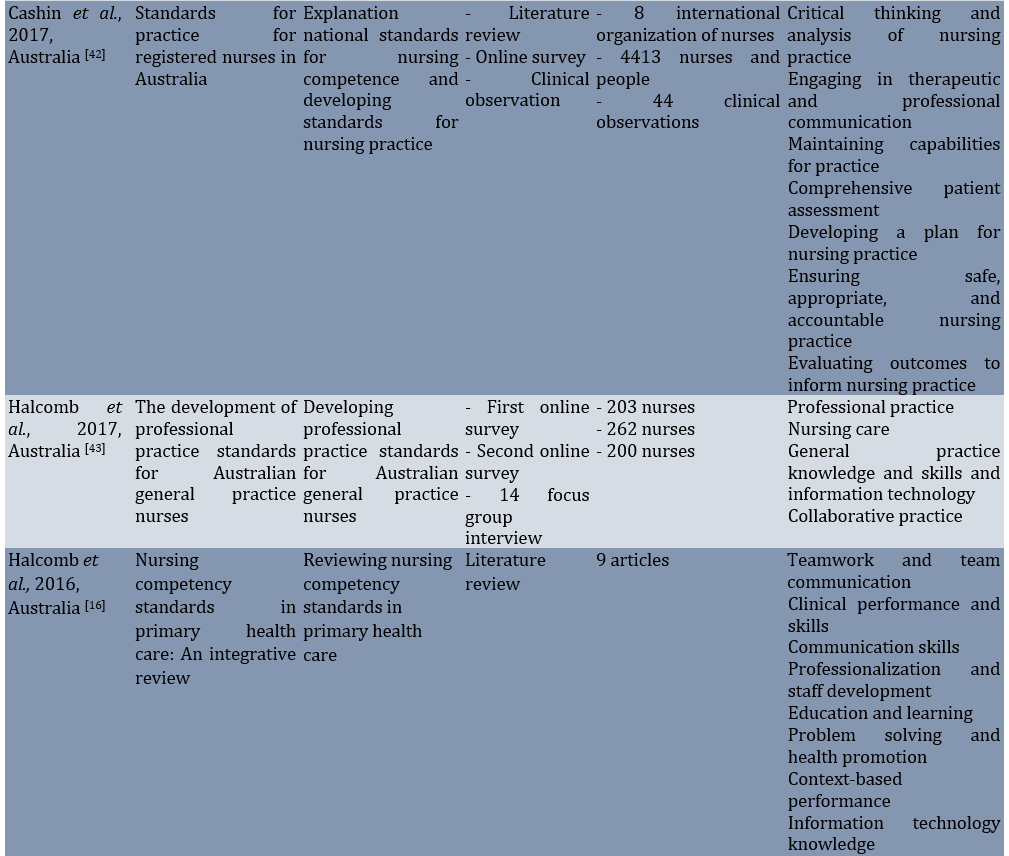

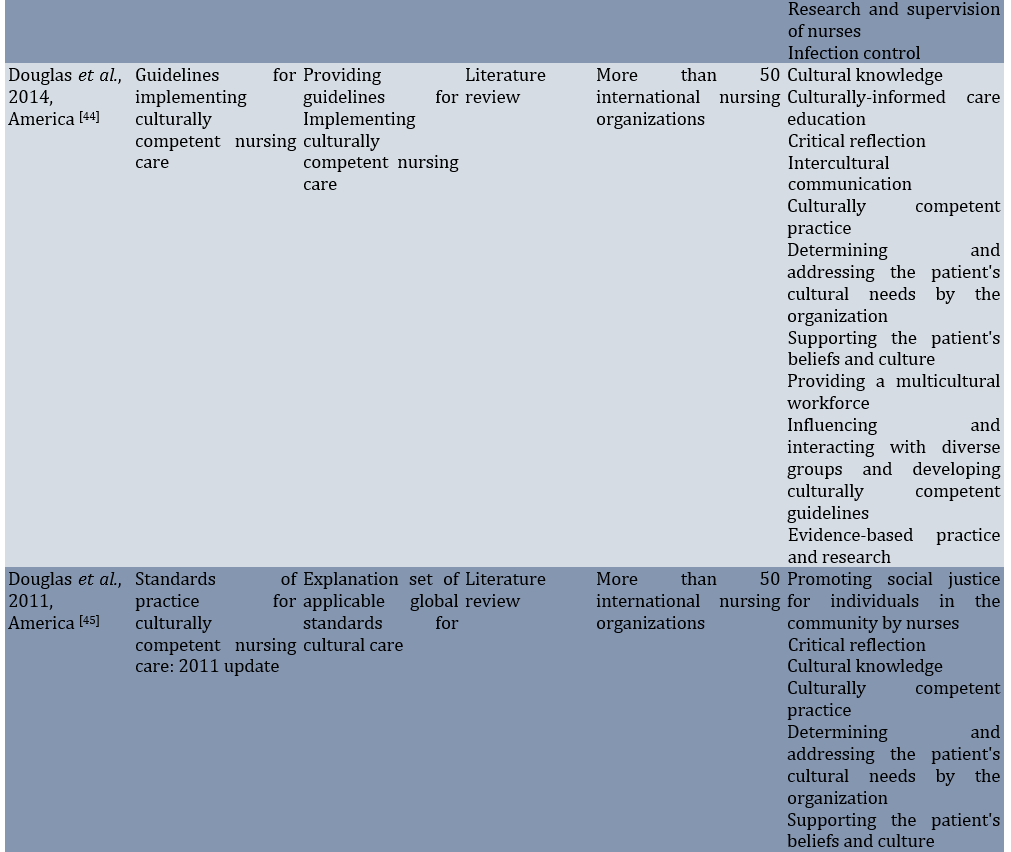

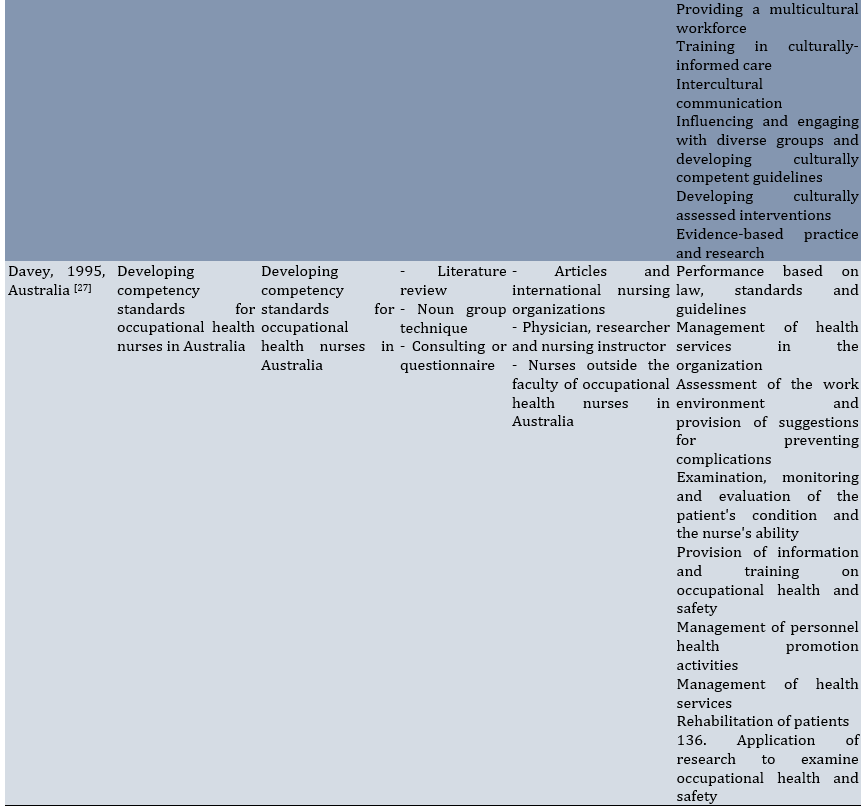

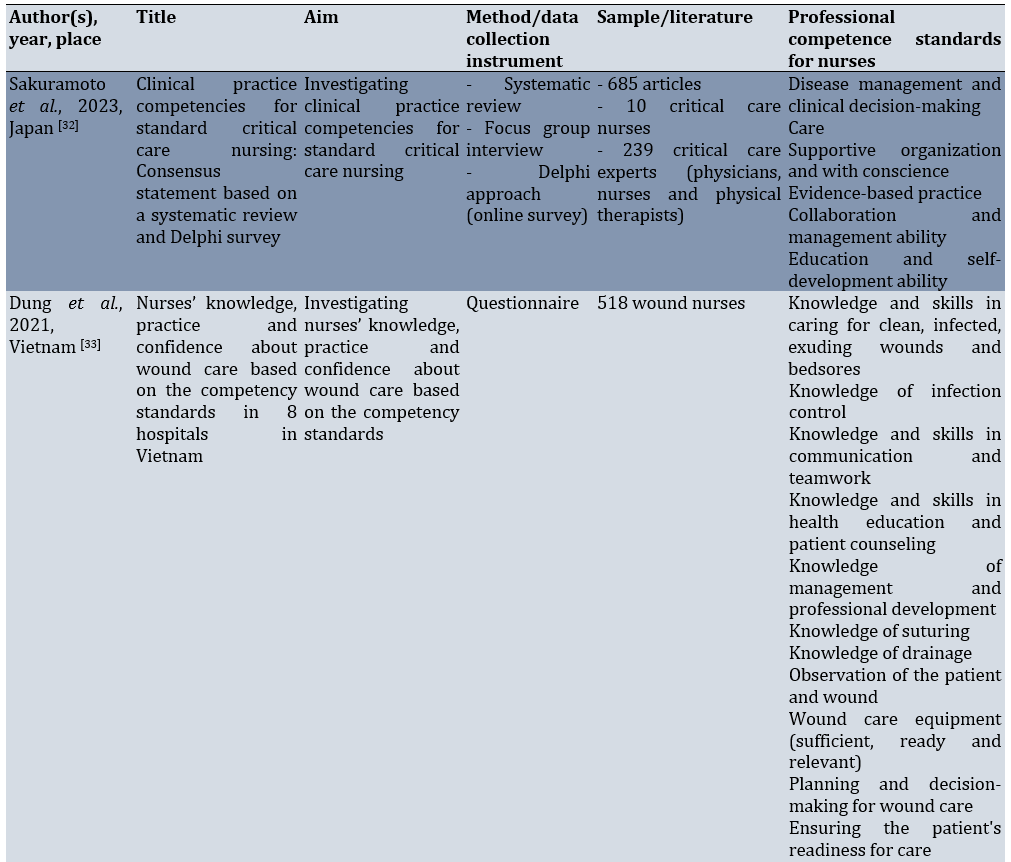

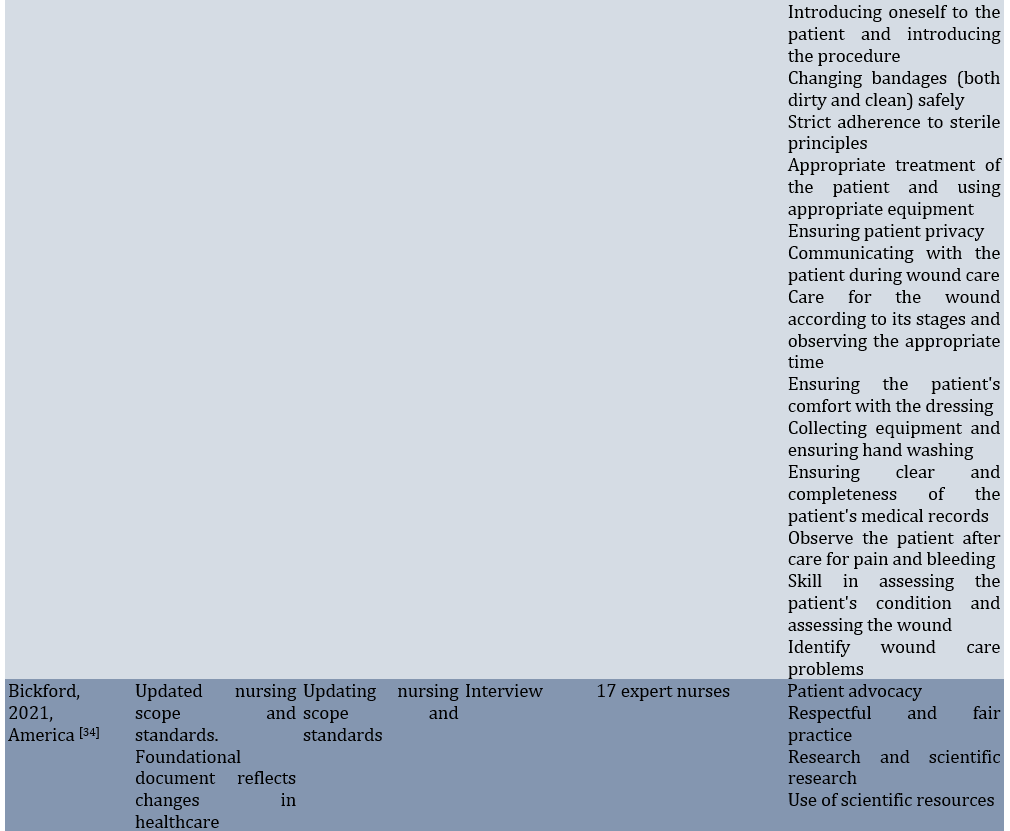

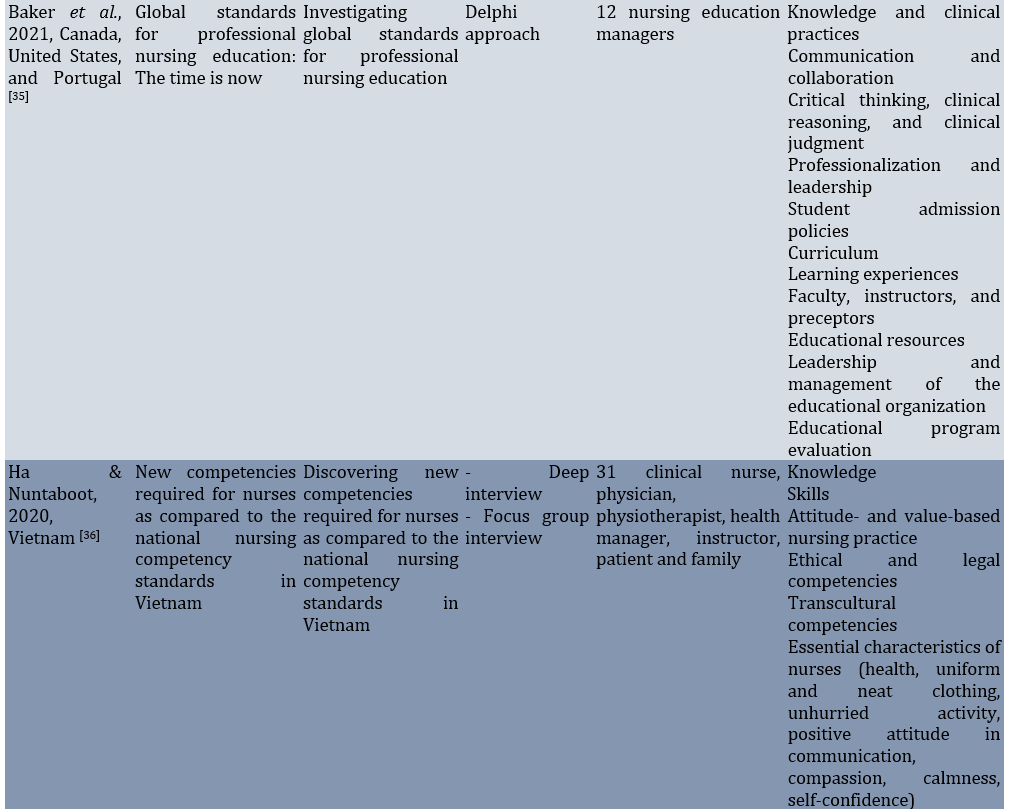

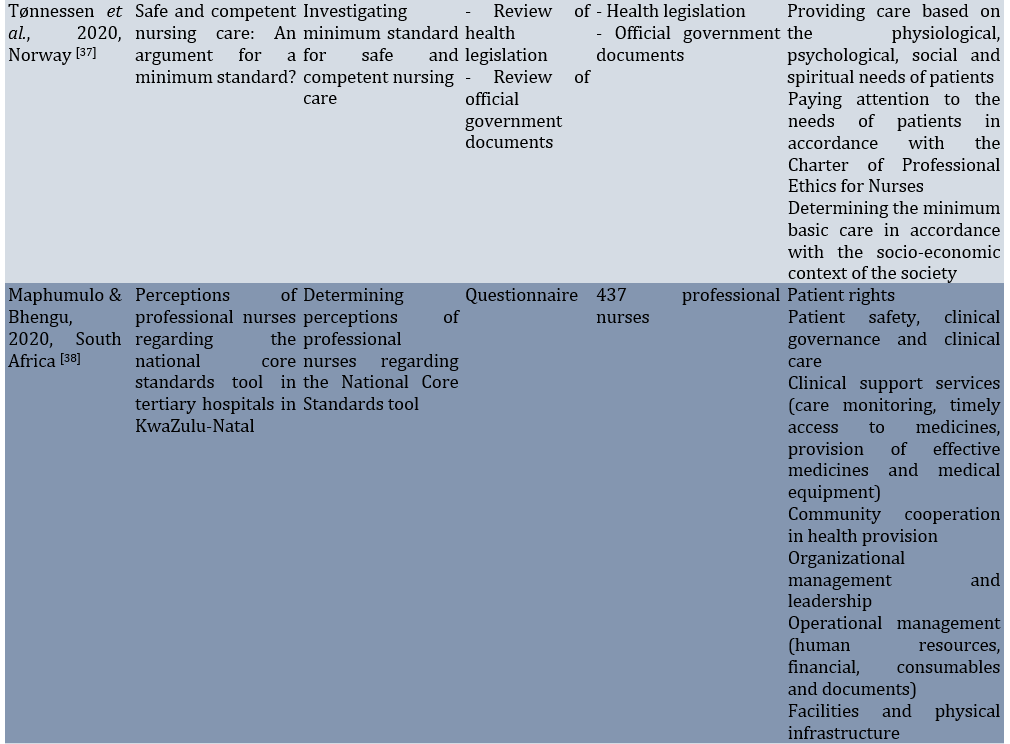

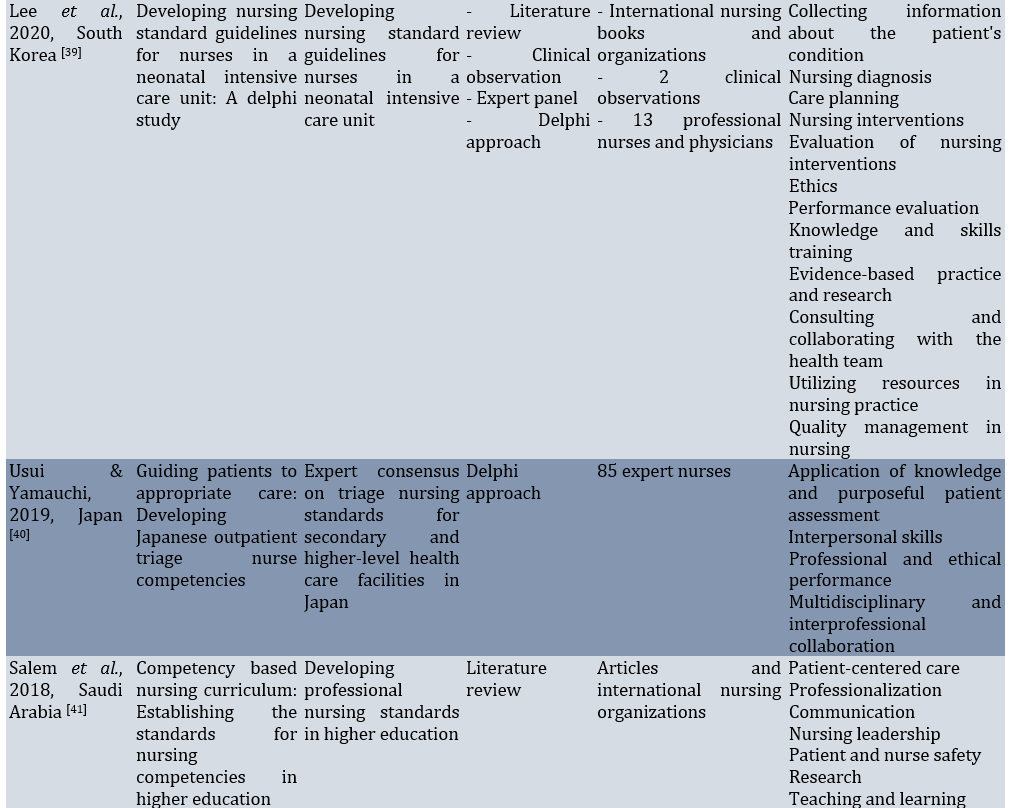

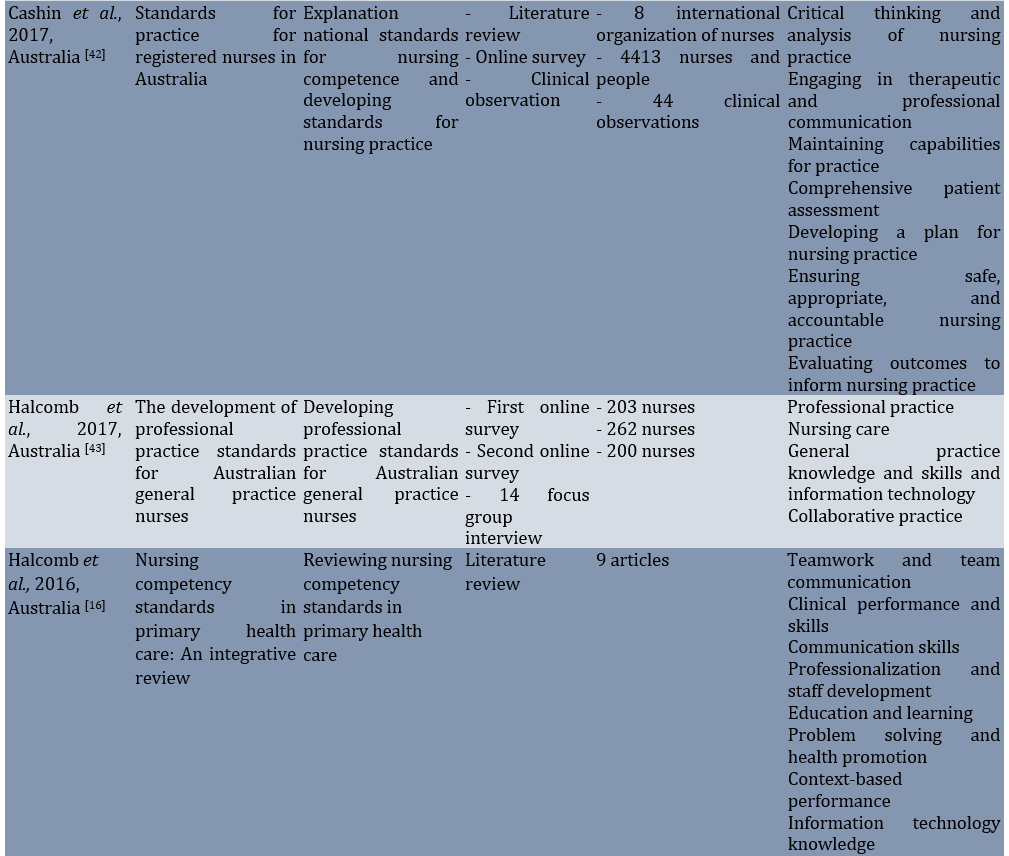

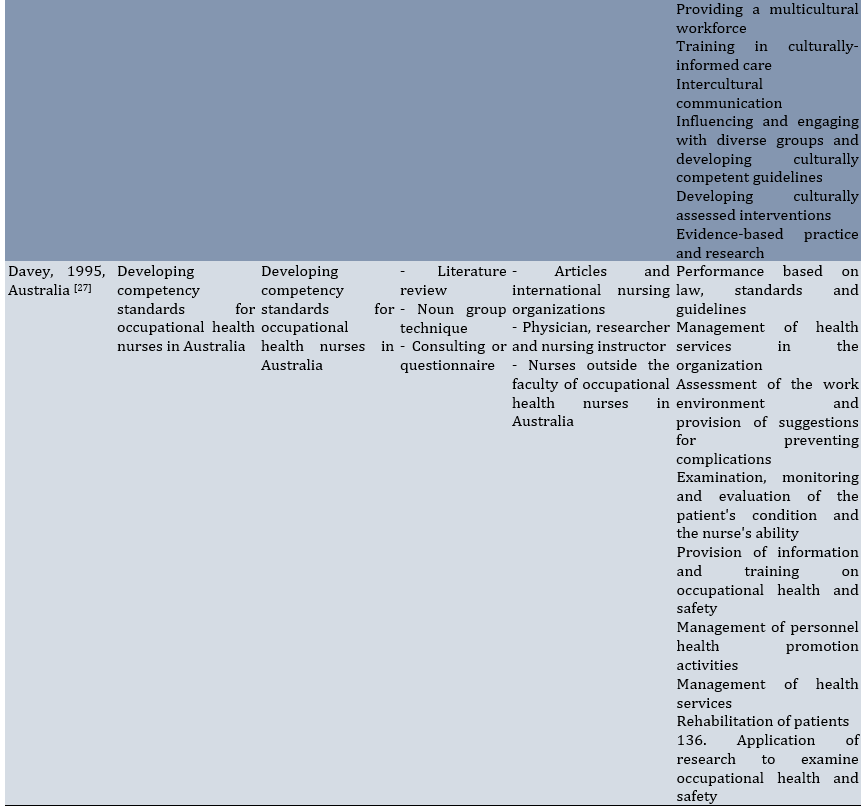

The obtained findings were synthesized after screening and assessing the quality of the documentation. A thematic synthesis approach was used for the data synthesis. From the examination of the 50 included documents, a total of 428 standards of competence for nurses were identified. Of these, 136 professional competence standards for nurses were extracted from 16 scientific articles (Table 3).

Table 3. Professional competence standards for nurses via scientific articles

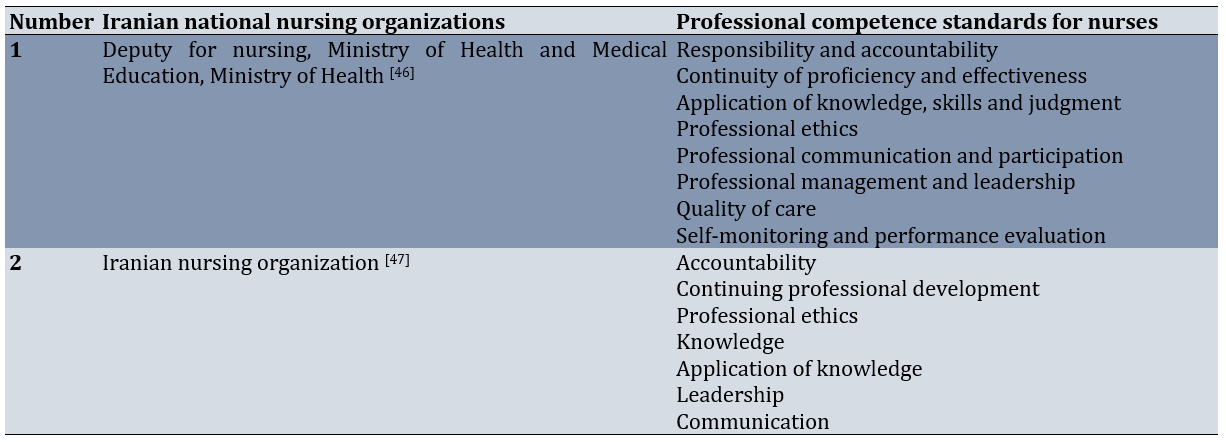

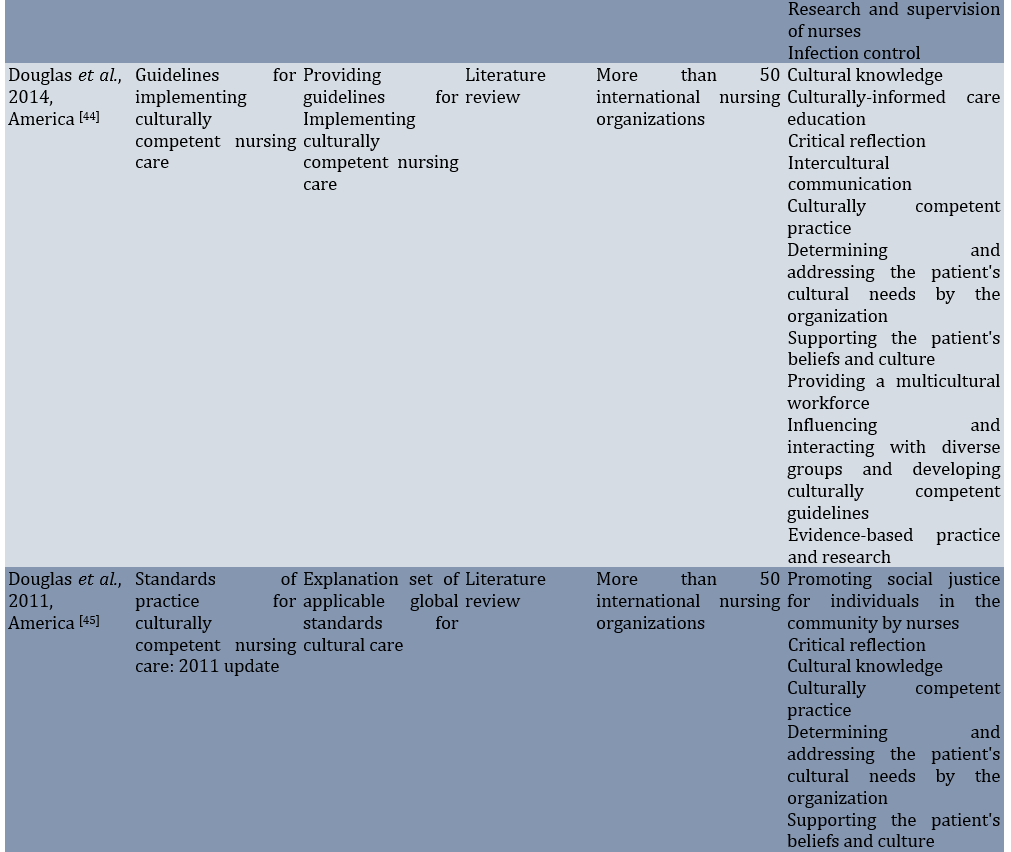

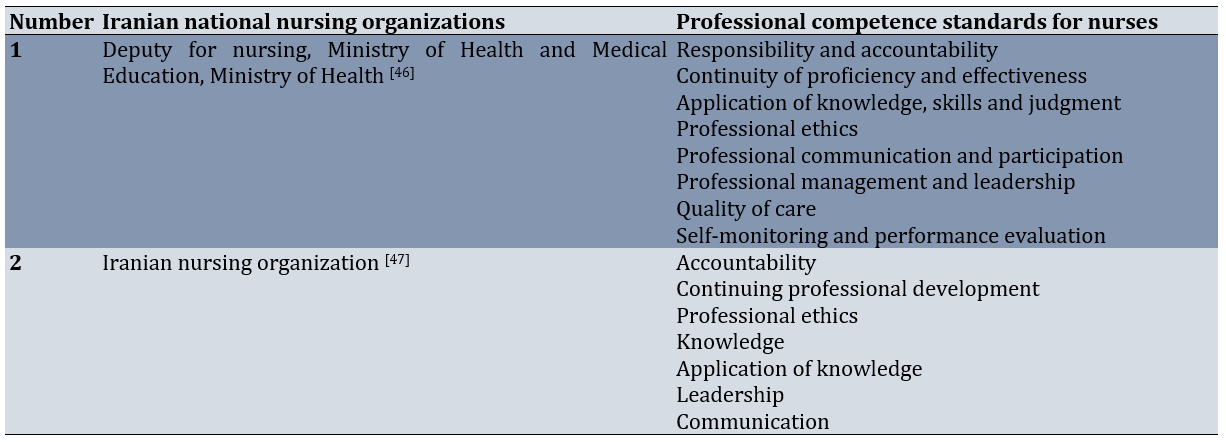

Fifteen standards were identified from two national nursing organizations (Table 4).

Table 4. Professional competence standards for nurses via the Iranian national nursing organizations

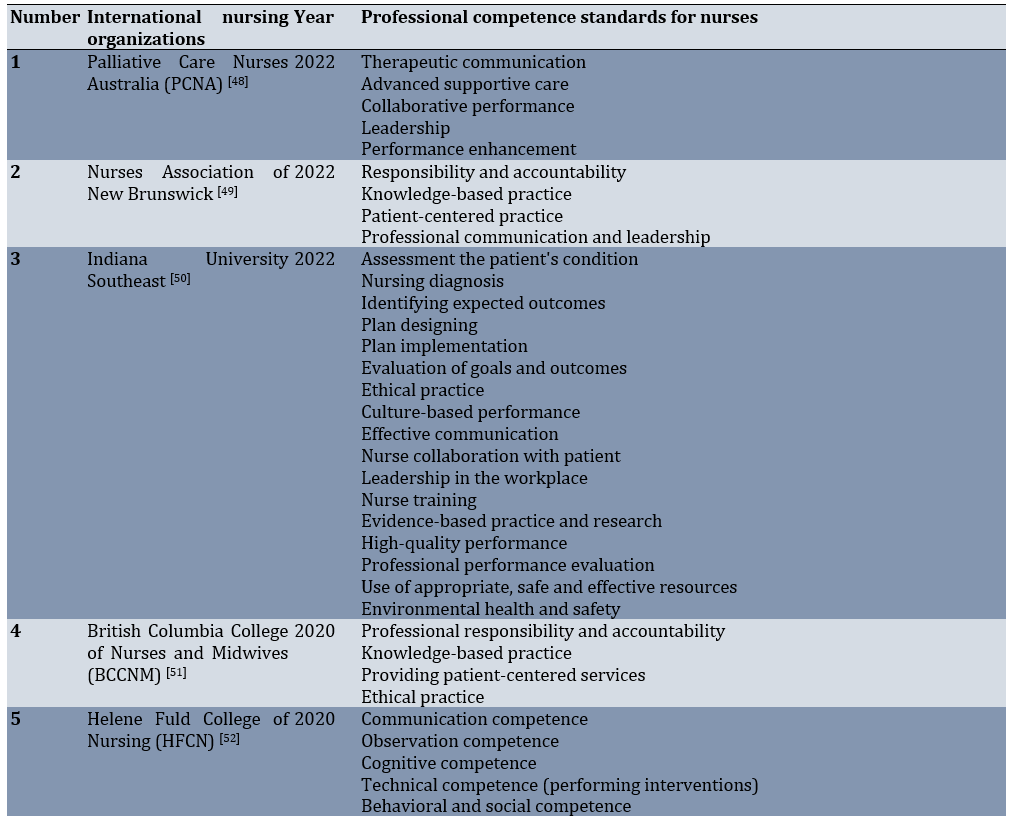

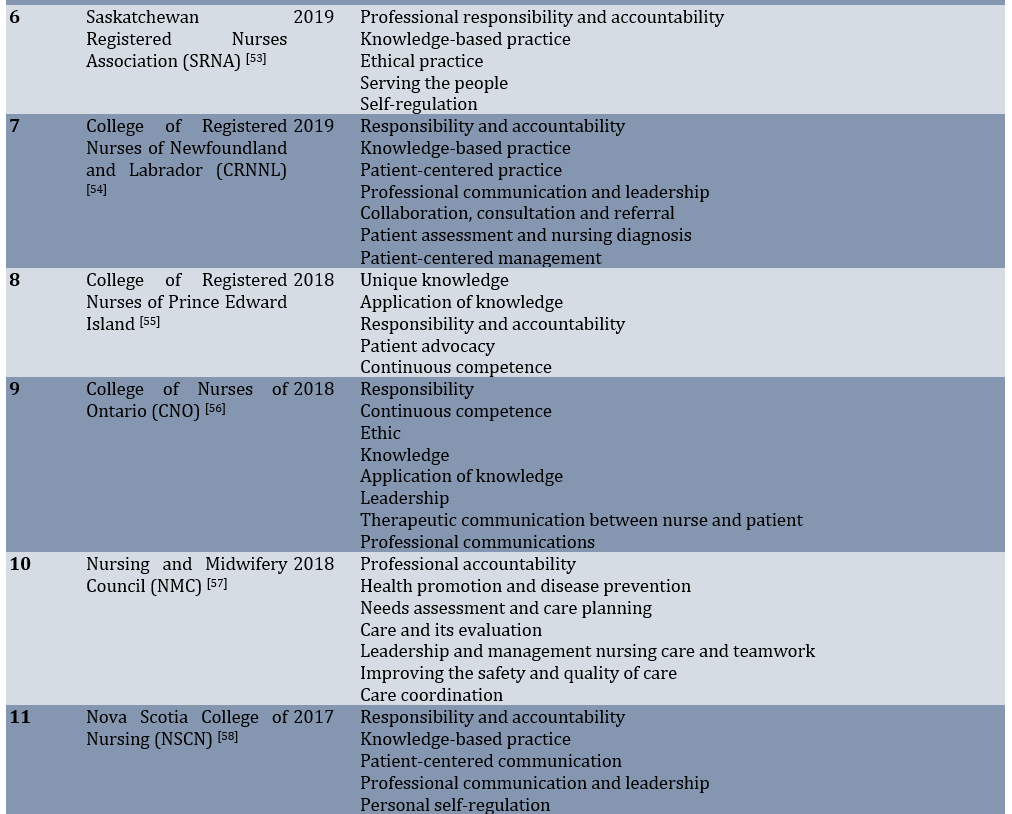

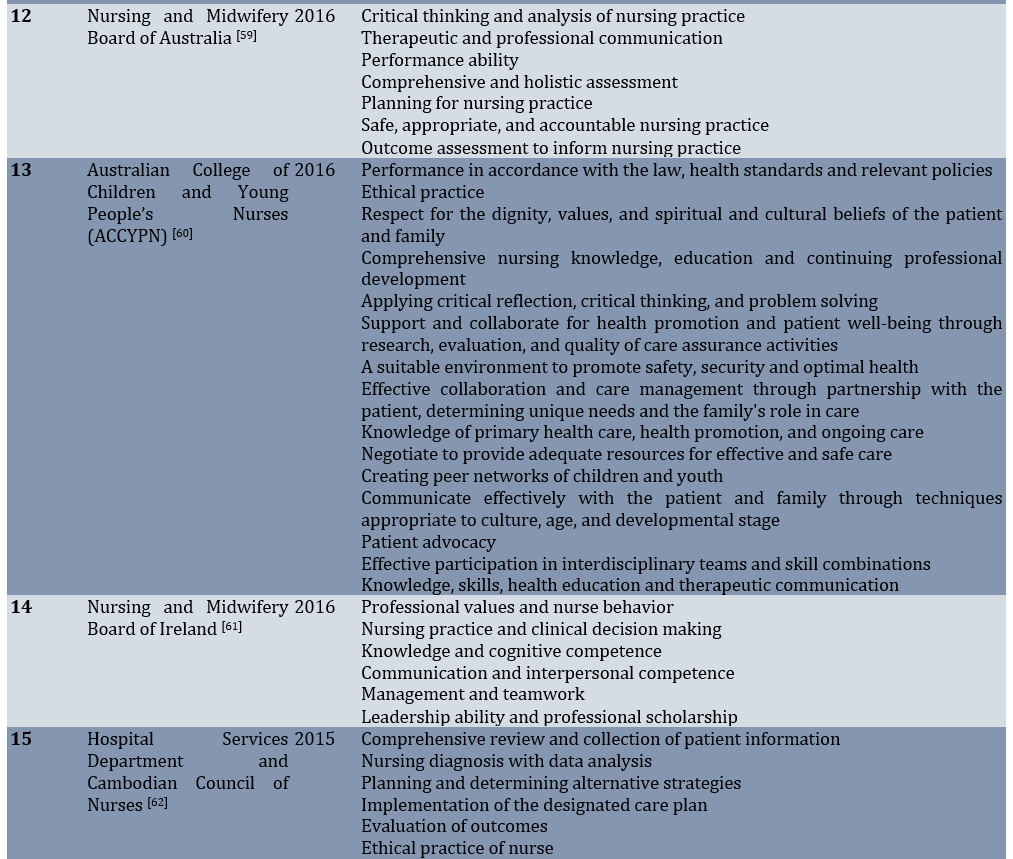

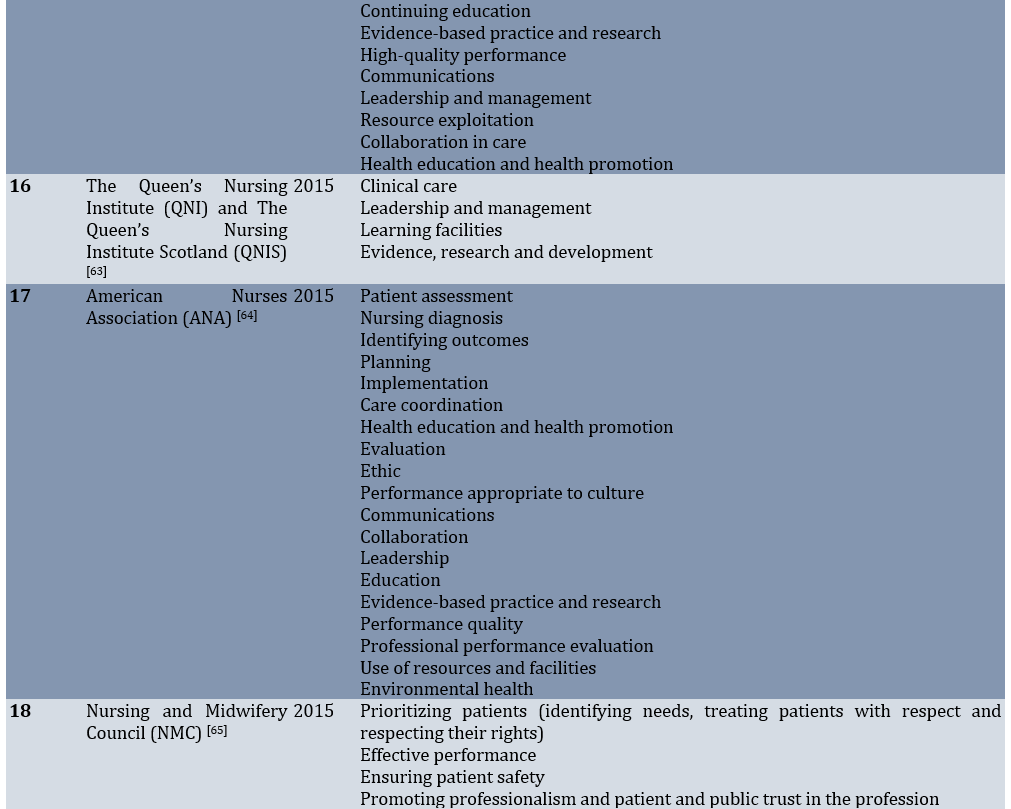

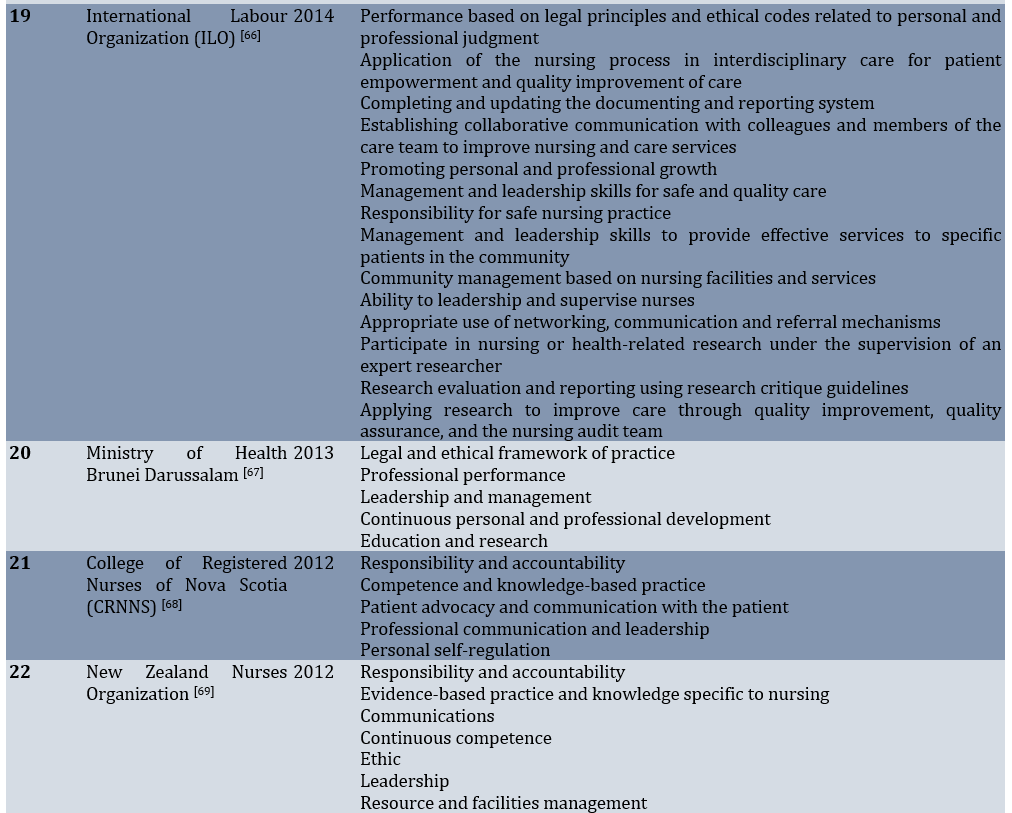

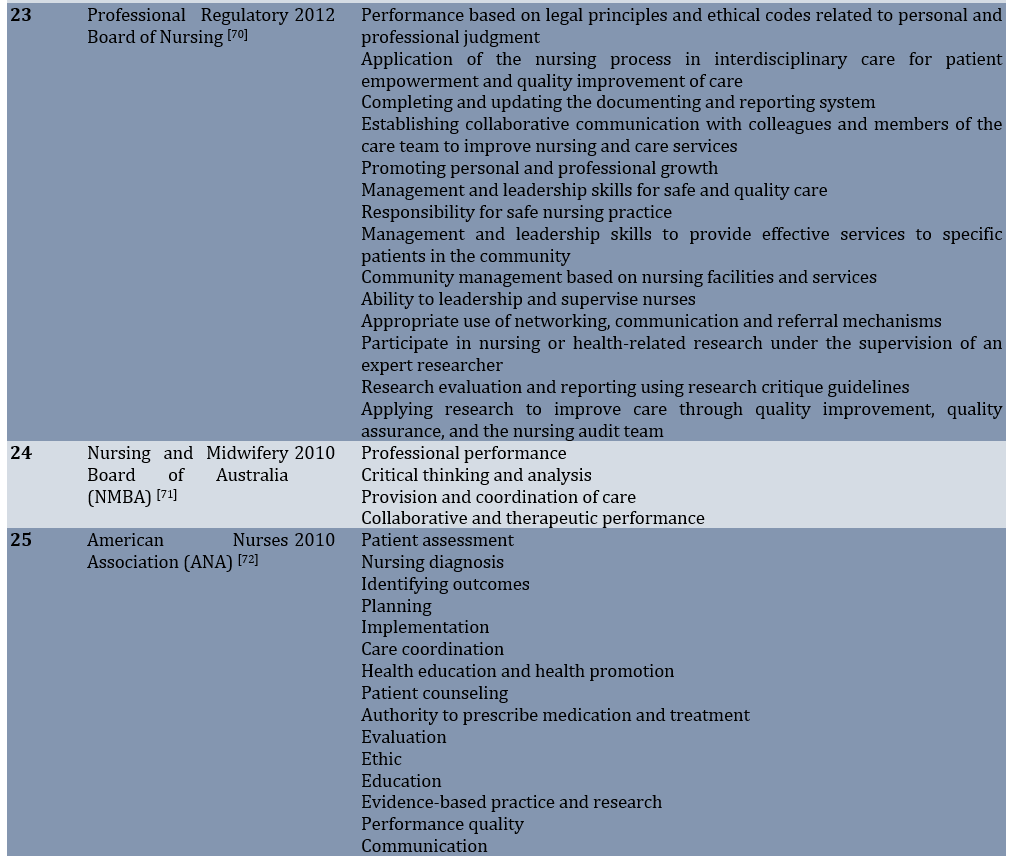

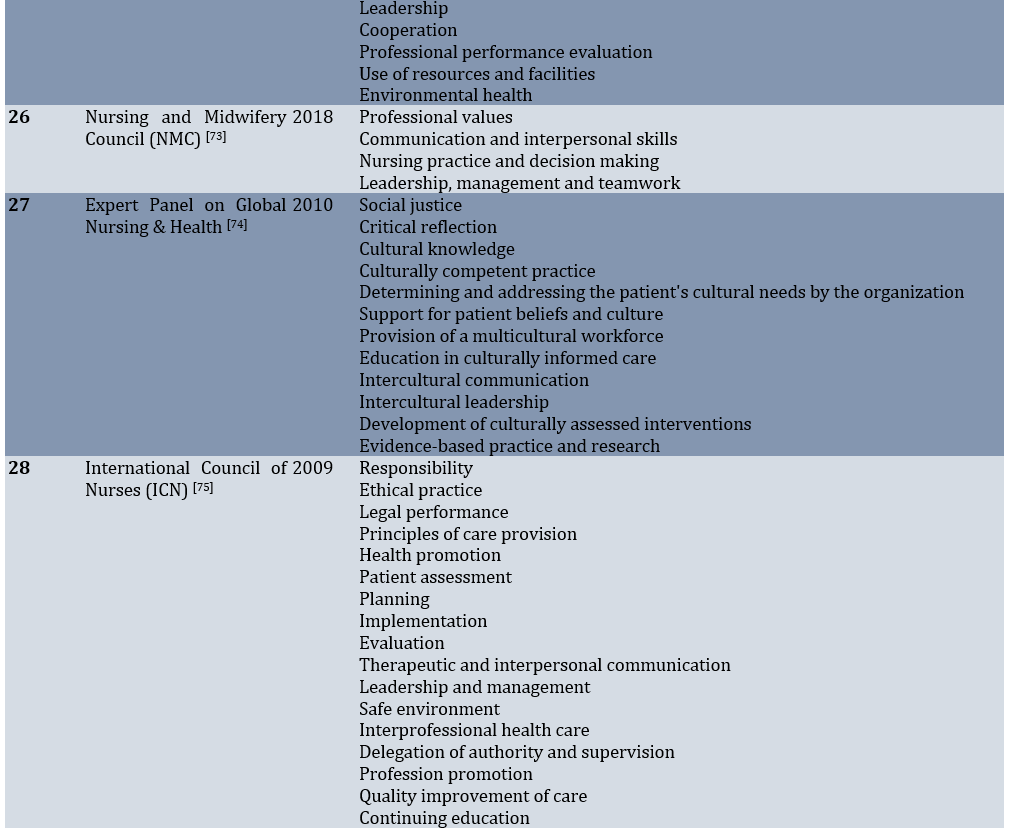

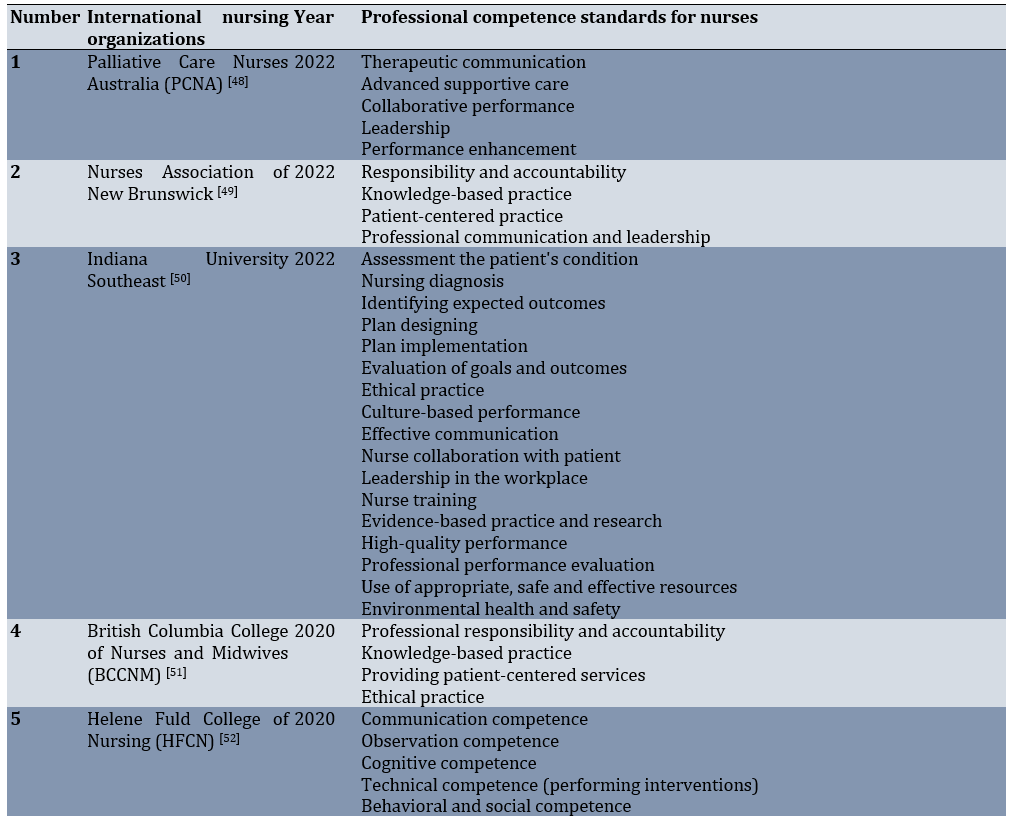

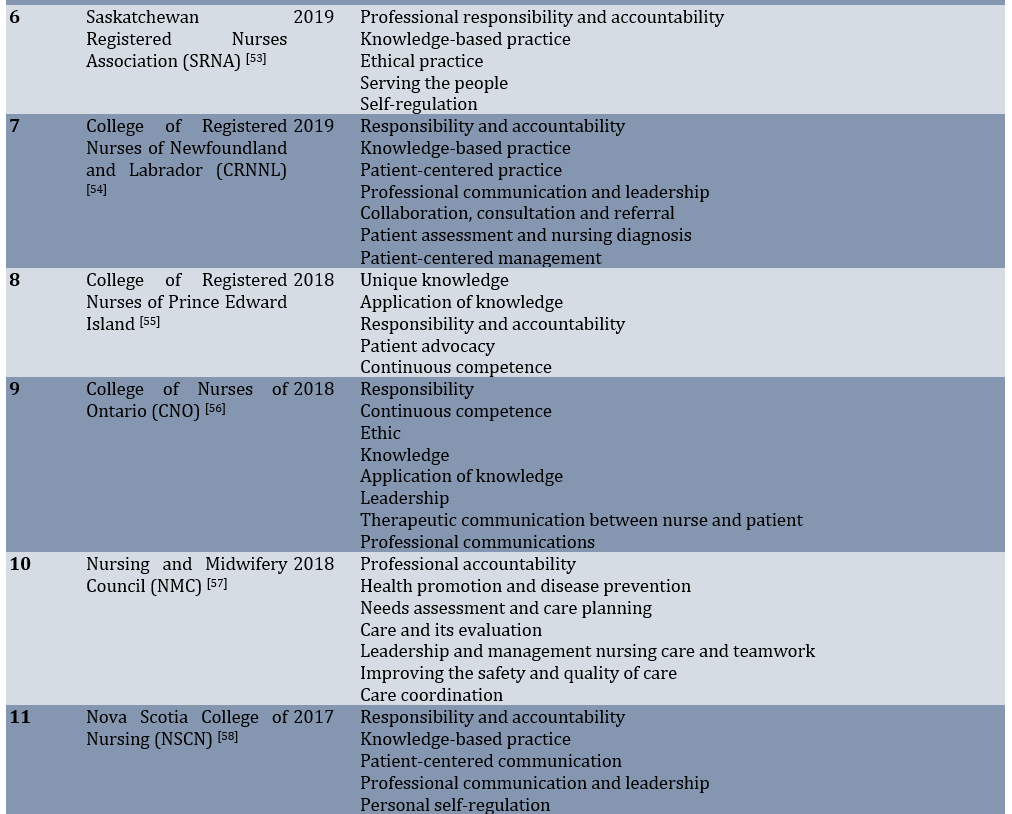

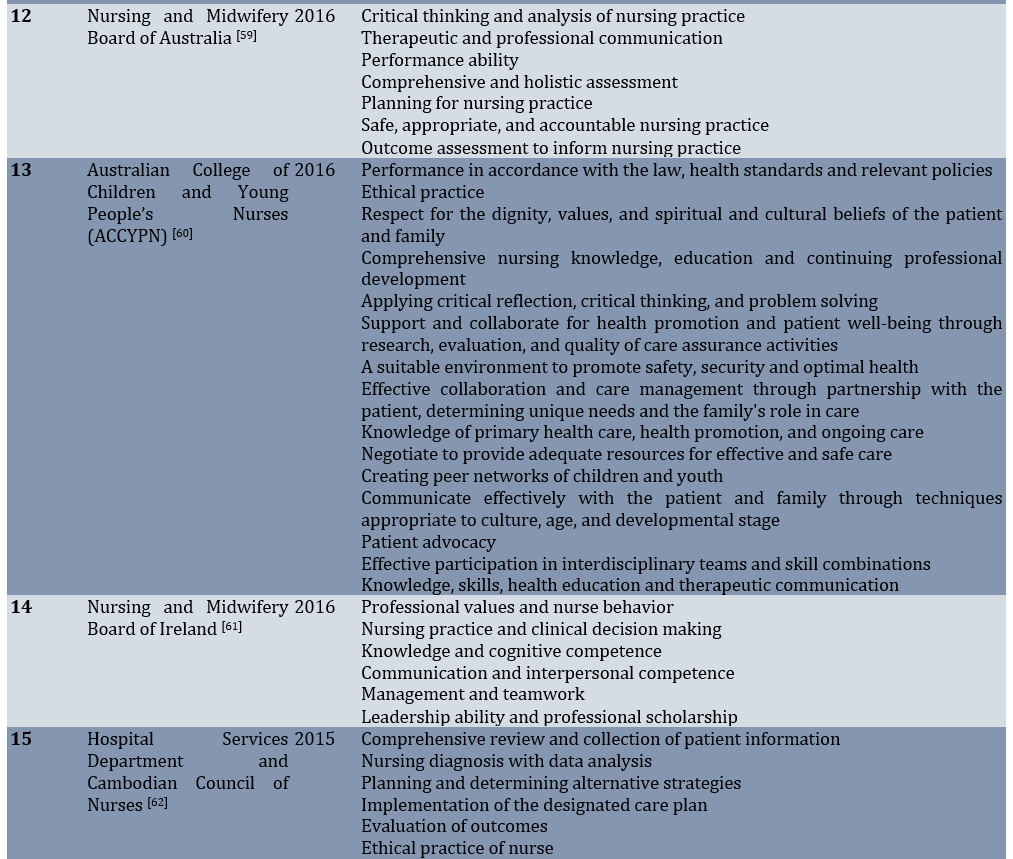

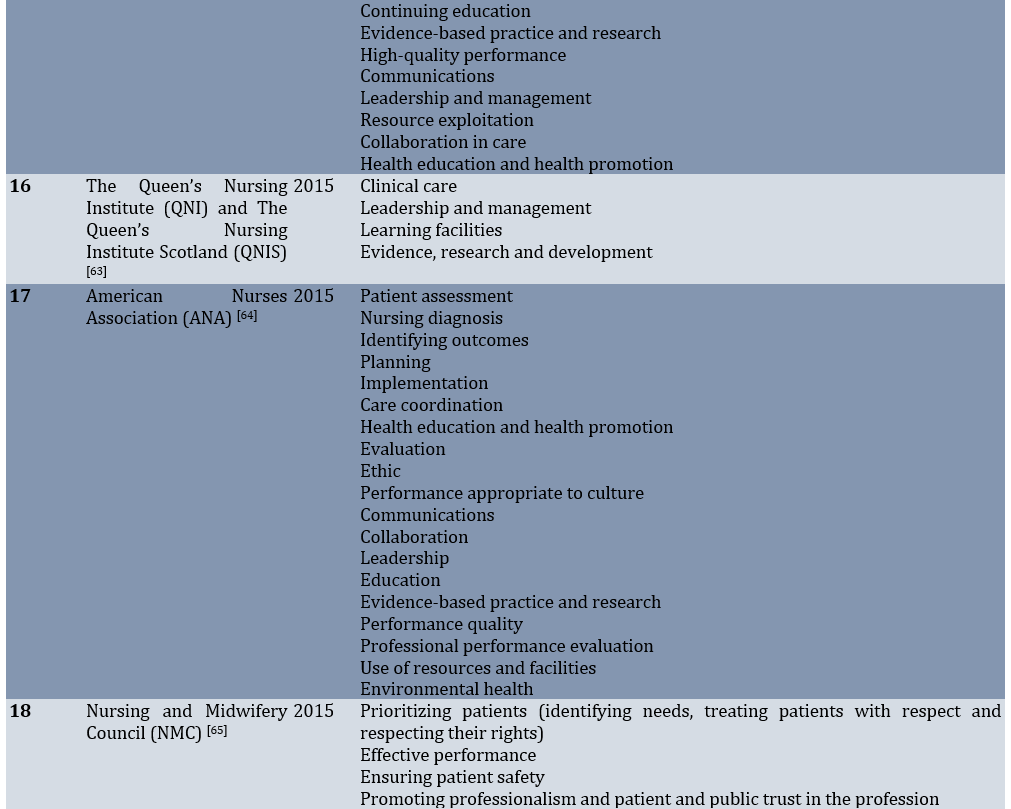

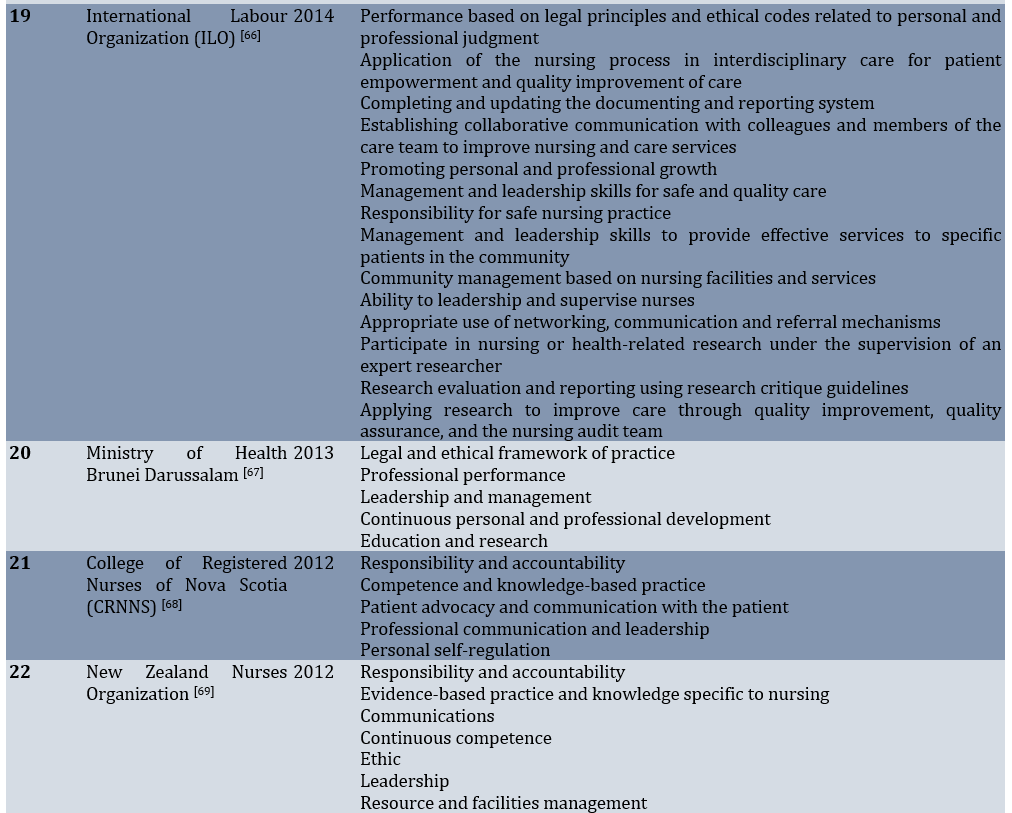

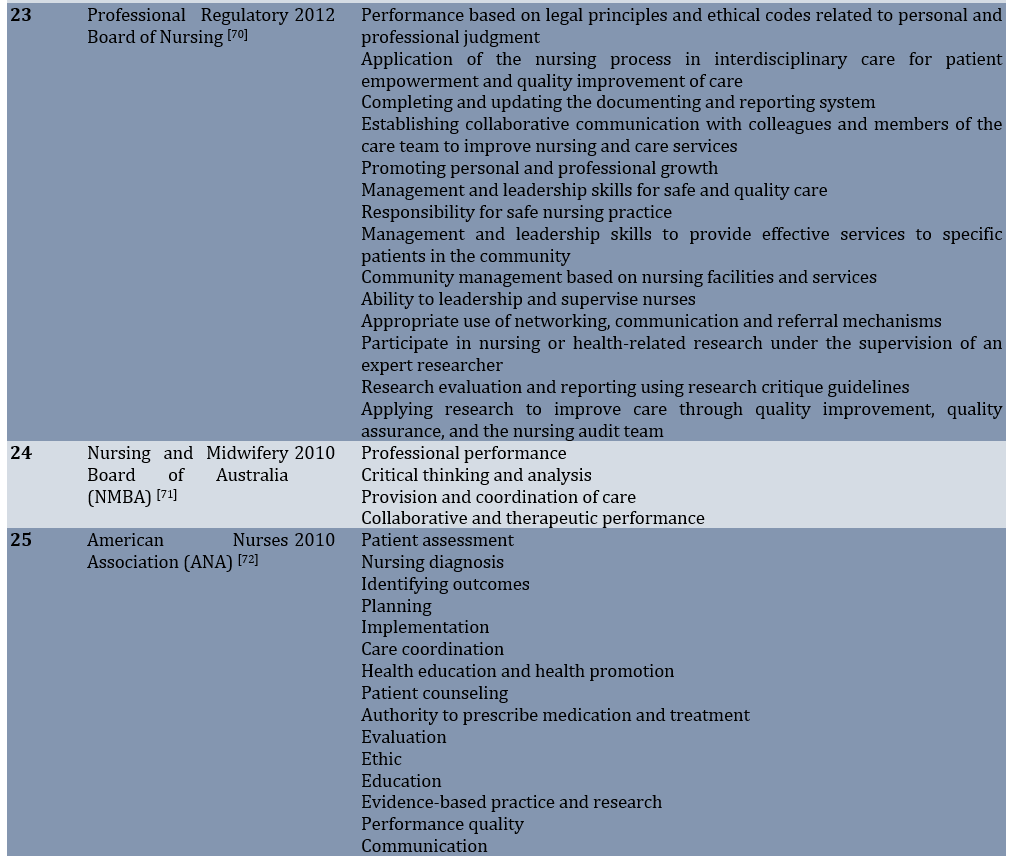

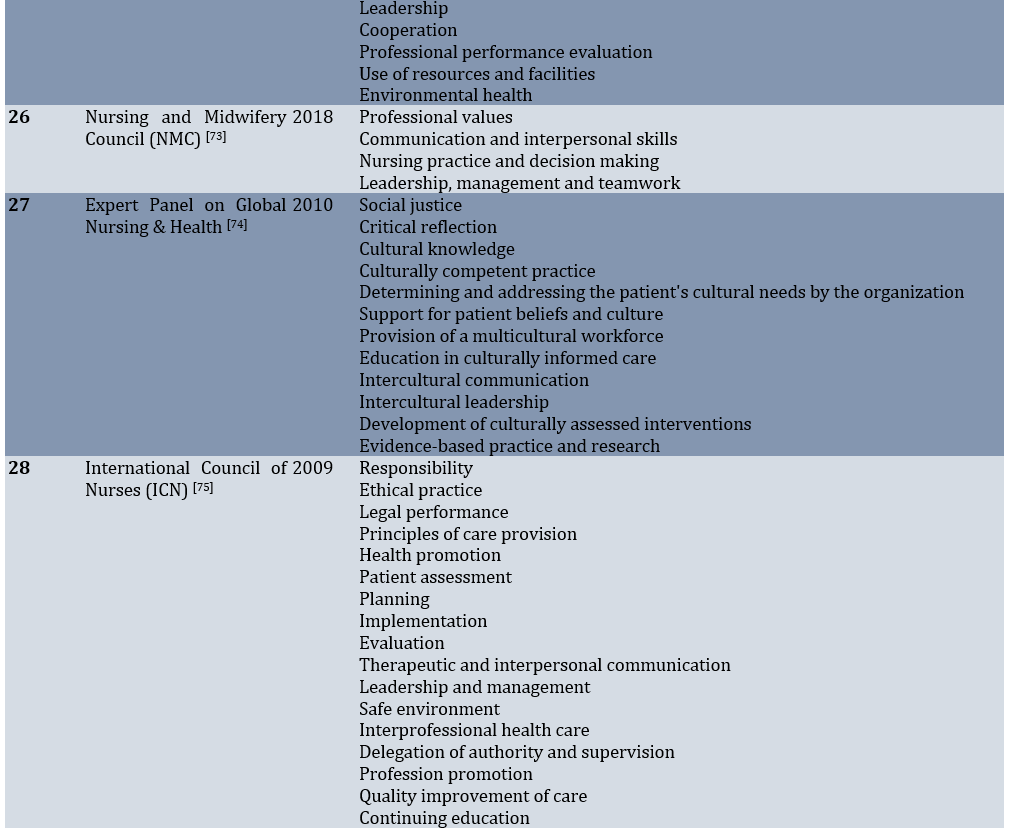

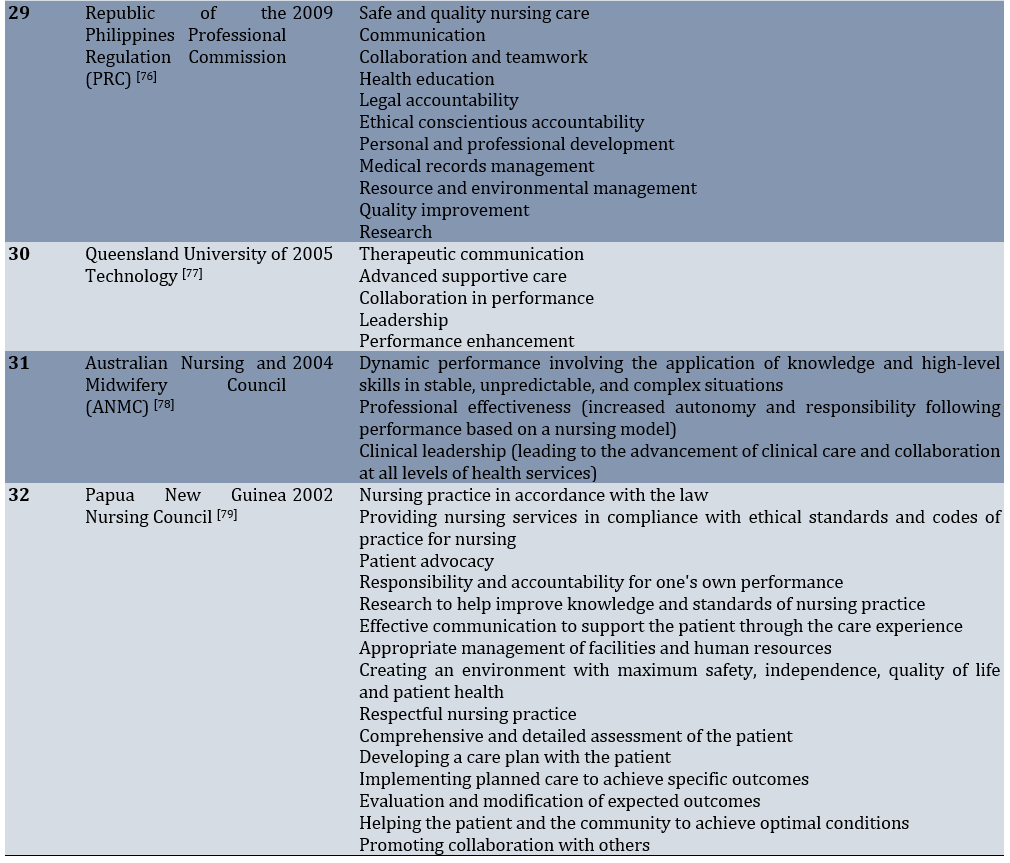

Also, 277 standards were identified from 32 international nursing organizations (Table 5).

Table 5. Professional competence standards for nurses via international nursing organizations

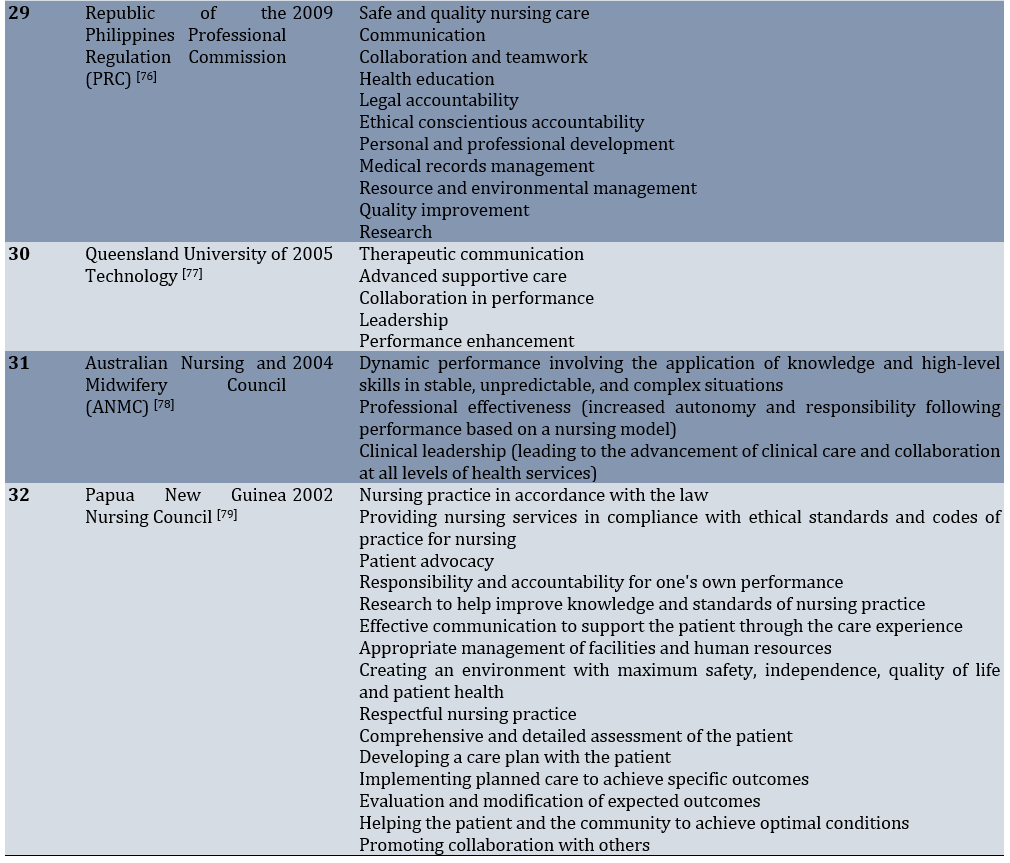

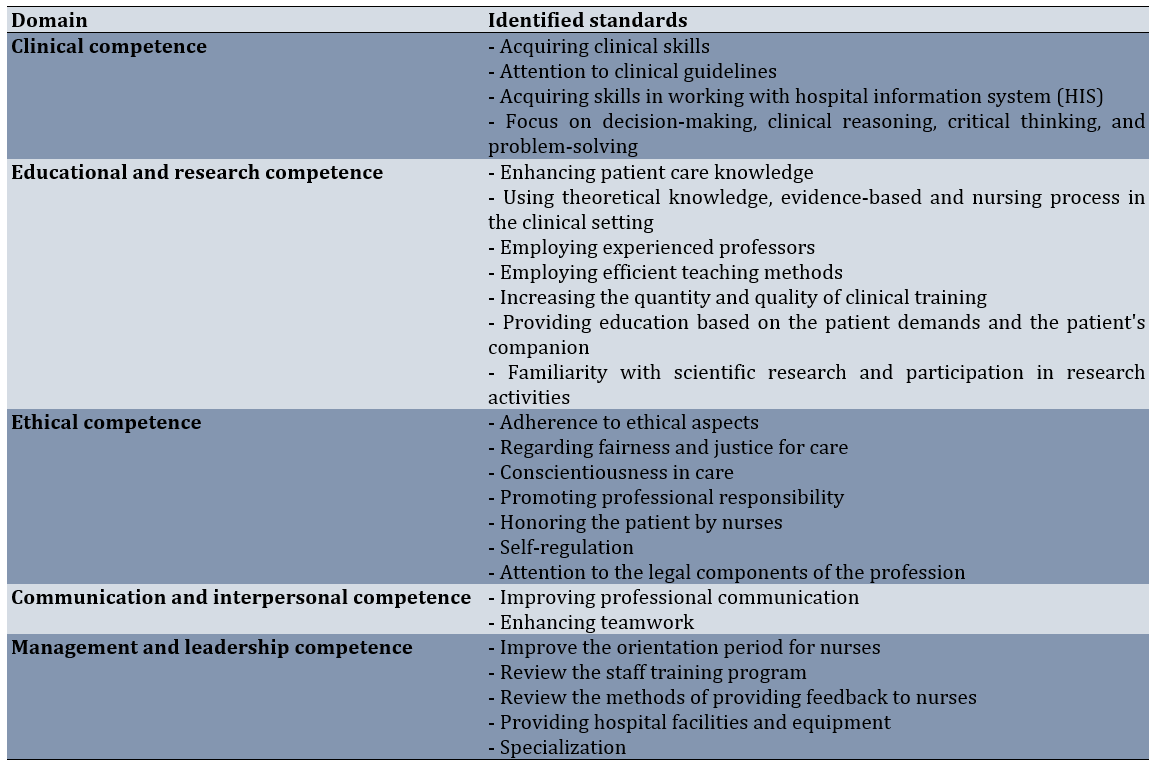

Following the synthesis of the findings from the systematic review, comparable standards were compared and consolidated, which were then grouped and organized into domains. The synthesis of the studies led to the identification of five domains of professional competence standards for nurses, which included clinical competence, educational and research competence, ethical competence, communication and interpersonal competence, and management and leadership competence (Table 6).

Table 6. Domains and identified standards of nursing professional competence

Clinical competence

Clinical competence is often regarded as one of the most basic and fundamental professional competencies for nurses. The ability of nurses to perform various technical skills has always been considered one of the elements essential for developing competent nurses, and the application of nursing knowledge has been an important factor in enhancing their clinical competence. Nurses should acquire clinical skills and pay attention to clinical guidelines to provide effective services. Moreover, proficiency in working with hospital information systems (HIS) is considered a prerequisite for nurses to achieve clinical competence. Standards, such as a focus on decision-making, clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and problem-solving have been introduced as key elements of clinical competence.

Educational and research competence

In addition to strengthening the clinical competencies of nurses, the central elements of this competence area include enhancing patient care knowledge and utilizing theoretical knowledge, evidence-based practices, and the nursing process in the clinical setting. By regularly reviewing theoretical knowledge and applying evidence-based practices along with the nursing process, nurses can help consolidate their knowledge and prevent forgetting. The completion of this competence involves considering teaching and learning in universities, including employing experienced professors, utilizing effective teaching methods, and increasing the quantity and quality of clinical training. In addition to providing care, nurses play an important role in delivering education based on patient demands and those of the patient’s companions. Familiarity with scientific research and participation in research activities are essential for nurses to acquire research competencies.

Ethical competence

In addition to the need for nurses to possess clinical knowledge and skills, it is also important to pay attention to ethical values when caring for patients. Focusing on the patient as the center of care will help achieve competence. In this regard, adherence to ethical principles, such as fairness and justice in care, conscientiousness in caregiving, and the promotion of professional responsibility, are considered key factors in the ethical competence of nurses. Moreover, honoring the patient, self-regulation, and attention to the legal components of the profession are effective in achieving this competence.

Communication and interpersonal competence

Improving professional communication is a crucial aspect of nurses’ competence and encompasses various dimensions, including relationships between nurses and their colleagues, doctors, patients, and patients’ families. We identified communication and interpersonal relationships within the care team as one of the key factors in achieving competence and providing quality care. In this regard, enhancing professional communication and teamwork is essential for ensuring this competence. Nurses will be able to develop their teamwork skills by acquiring professional communication skills. In addition to developing communication and teamwork abilities, it is essential for organizations to promote teamwork and cultivate a supportive culture. In this context, members of the health team must be fully aware of their job descriptions and act accordingly.

Management and leadership competence

The competencies introduced are not sufficient on their own and that a focus on management and leadership competencies is important. Factors such as improving the orientation period for nurses, reviewing the staff training program, evaluating the methods of providing feedback to nurses, ensuring access to hospital facilities and equipment, and promoting specialization are some of the areas that health managers and leaders can focus on to ensure that nurses are adequately supported and trained.

Discussion

This study was conducted to establish professional competence standards for nurses. The findings were obtained through a systematic review of the literature and guidelines from nursing organizations. Five domains of competence were identified, comprising 25 standards. For nurses, four, seven, seven, two, and five standards of professional competence were identified in the five domains, including clinical, educational and research, ethical, communication and interpersonal, and management and leadership.

Clinical competence was one of the identified domains in the systematic review. The four standards identified within the clinical competence domain included acquiring clinical skills, adhering to clinical guidelines, developing skills in working with HISs, and focusing on decision-making, clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and problem-solving.

Nurses can provide high-quality and safe care to patients by relying on their clinical knowledge [80]. Our study demonstrated that attention to clinical skills and guidelines is recognized as one of the professional competencies of nurses. Several studies included in the review confirmed the results of this study, such as the research conducted by Ha & Nuntaboot, identifying nursing skills and practice as new competencies required for nurses compared to the national nursing competence standards in Vietnam [36].

Halcomb et al. report professional practice and nursing care as the professional standards of practice for nurses in Australia [43]. In other studies and nursing organizations, clinical practice and skills have been reported as one of the competencies for nurses [16, 67]. The acquisition of skills for working with HISs was identified as an additional clinical competence standard, in line with the findings of the study recognizing information technology knowledge and skills as a competence standard [16, 43].

This is important for accessing patient clinical records, providing diagnostic and therapeutic services, and monitoring patient treatment. The computer literacy of nurses is a prerequisite for gaining competence and delivering quality, cost-effective care [81]. Other clinical competence standards included the reinforcement of decision-making, clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and problem-solving. Some studies have shown that clinical decision-making is one of the competencies essential for clinical performance in nursing care [32]. Clinical reasoning and critical thinking [35, 42] are also vital for the training and competence of nurses. According to Halcomb et al., problem-solving is recognized as one of the nursing competence standards in primary care [16]. This finding aligns with international guidelines, such as those from the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, which emphasize critical thinking and analysis of nursing performance as essential nursing competence standards [59].

One of the domains most frequently addressed in our systematic review was educational and research competence. This domain consisted of seven identified standards: enhancing patient care knowledge, using theoretical knowledge, applying evidence-based practices and the nursing process in the clinical setting, employing experienced professors, utilizing effective teaching methods, increasing the quantity and quality of clinical training, providing education based on patient demands and those of the patient’s companions, and fostering familiarity with scientific research and participation in research activities.

Some studies included indicated that improving the competencies of nurses requires knowledge acquisition [35, 36]. Once knowledge is acquired, the application of theoretical knowledge, scientific evidence, and the nursing process in clinical practice may enhance educational and research competence. Several studies have shown that the use of evidence-based practice is effective in improving nursing competence, corroborating the results of our study [32, 39, 44, 45]. This finding aligns with the emphasis placed by the American Nurses Association on the importance of evidence-based practice in nursing [72]. In accordance with the findings of this study, the nursing process is established as an important standard of competence for nurses by Lee et al. [39]. University professors play a crucial role in qualifying nurses through their training. Professors are responsible for teaching nursing students and preparing them for future careers in healthcare. To acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for providing quality care, it is essential that teaching institutions, especially professors, recognize the significance of their work in training professionals and develop the attitudes and skills needed for success.

Clinical educators must possess characteristics, such as effective communication with students, professional skills, evaluation skills, teaching abilities, and personal attributes for teaching. Therefore, it is essential for professors to evaluate their teaching and improve their practice by identifying aspects of their instruction that are incomplete [82]. Baker et al. report the curriculum, learning experiences, faculty, instructors, mentors, and educational resources as standards for the competence of nurses [35]. Supporting these findings, teaching and learning have been shown to be effective in the development of competence [16, 41]. Need-based education for patients and their families is another standard introduced in the study by Dung et al. as a component of nurse competence [33], and this is consistent with our results. In addition to educational competence, research competence is also a requirement for nurses’ professional competence. In this respect, the studies reviewed indicate that scientific inquiry and research are among the standards of competence for nurses [34, 41], which is confirmed by the results of this study.

Ethical competence is considered an important domain of professional competence for nurses. In the ethical competence domain, seven identified standards include adherence to ethical principles, fairness and justice in care, conscientiousness in care, promoting professional responsibility, honoring patients, self-regulation, and attention to the legal components of the profession.

It is necessary for nurses to acquire professional competencies through ethical and legal competence [36] and ethical practice [39, 40]. The College of Nurses of Ontario also considers ethics to be a standard of competence [56]. Bickford identifies fair practice as one of the competence standards for nurses in the field of nursing [34]. In another study, the promotion of equity by nurses was based on standards derived from a systematic review of several international organizations [45]. Ethical conscientious accountability was another standard that the Republic of the Philippines Professional Regulation Commission deemed important [76], and our study’s results reinforce this.

Another frequently cited standard is responsibility. The International Labour Organization and the Professional Regulatory Board of Nursing are among the nursing organizations that consider this standard essential [66, 70], supporting our results. It was found that honoring patients was effective in ensuring the ethical competence of nurses. Consistent with our findings, patient advocacy has been identified as a standard competence for nurses [34]. The Nursing and Midwifery Council also considers that prioritizing patients through identifying their demands, demonstrating respectful behavior, and upholding patients’ rights is an effective way to develop competent nurses [65]. Self-regulation of nurses is another factor in promoting professional competence, a result confirmed by several studies included in the review [53, 58, 68].

Improving professional communication and enhancing teamwork were two standards in the domain of communication and interpersonal competence. A study by Parnikh et al. has shown a positive and significant relationship between professional communication and professional engagement, as well as interest in one’s job, leading to quality care and patient safety [83]. Improving professional communication aligns with the guidelines for nurses, which consider this standard an integral part of nursing competencies [46, 47]. Regarding teamwork enhancement, studies highlight the importance of focusing on teamwork as one of the key standards for improving nurses’ competencies [40, 43]. Therefore, strengthening communication and teamwork skills should be prioritized in the training of nurses.

Finally, in the domain of management and leadership competence, five standards were identified: improving the orientation period for nurses, reviewing the staff training program, assessing the methods of providing feedback to nurses, ensuring the availability of hospital facilities and equipment, and promoting specialization.

Improving in-service training was another standard identified as a prerequisite for enhancing professional aptitude. Supporting the findings of this study, Sato & Ishimaru argue that in-service training is necessary to improve nurses’ competencies [84]. The training provided should be tailored to the educational needs of nurses. These needs can be assessed through an analysis of educational requirements [85]. Indiana University Southeast also considers that the training of nurses is a factor in improving their competence [50], which aligns with our results.

Another standard identified was the review of the methods used to provide feedback to nurses. Feedback is a crucial component of nursing. If nurses do not receive feedback about their performance, they may assume they do not need to improve in any area. Therefore, nursing specialists should consider feedback as part of their learning process and monitor how they receive it. Feedback is most effective when provided in a supportive environment and on a regular basis. Nursing managers should ensure that they offer feedback in a timely manner and focus on specific aspects of an individual’s performance. This type of feedback is considered very valuable and useful, enabling individuals to assess their own skills and enhancing motivation, self-confidence, self-esteem, and abilities [86].

Providing hospital facilities and equipment is considered a standard of nursing competence. Maphumulo & Bhengu also emphasize the importance of facilities and physical infrastructure, in accordance with this study [38]. The physical environment, including the design and performance of hospital buildings, had a significant influence on nurses’ recruitment and retention. Available facilities can have a substantial impact on nurses’ performance and the quality of care provided to patients [87].

Our findings serve as a reliable source of information for nurses and the nursing management system regarding the standards of nursing competence. Attention has been given to some of the standards of professional competence for nurses. By considering these domains, managers can effectively address the needs for nurses’ professional competencies, train competent nurses, and improve the quality of healthcare.

Conclusion

Clinical competence, educational and research competence, ethical competence, communication and interpersonal competence, and management and leadership competence are five domains of competence based on articles and guidelines from nursing organizations.

Acknowledgments: We express our gratitude to the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The current study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.SUMS.NUMIMG.REC.1400.033, approval date: 2021.15.09).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors' Contribution: Zarshenas L (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Mehri Z (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Rakhshan M (Third Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Khademian Z (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Mehrabi M (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%); Jamshidi Z (Sixth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (10%)

Funding/Support: This study was financially supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Nurses make up a large proportion of the health workforce in many countries worldwide, and through the provision of services and basic care, they are a key component of healthcare systems [1]. The increasing role of nurses in healthcare has led to a growing need for them to fulfill a variety of roles [2]. This creates a high demand for nurses to work in various healthcare settings, including hospitals, public and private health centers, primary care centers, nursing homes, ambulatory surgery centers, schools, psychiatric centers, the military, industrial centers, healthcare research centers, universities, home care centers, and insurance companies [3]. As providers of comprehensive care to patients, nurses are expected to act in accordance with their professional responsibilities when caring for individuals [4]. In this regard, it should be noted that the improvement of healthcare quality is directly linked to the professional competence of nurses [5].

Professional competence has many dimensions and is influenced by a variety of factors [6]. It is one of the dimensions of competence and is an important and fundamental concept in the field of nursing [5]. The concept of professional competence is complex, multi-layered, and contextual [7]. To date, different dimensions of competence in nursing have been introduced; in this respect, the following can be mentioned: professional competence, interdisciplinary competence, clinical competence, individual competence, research competence, educational competence, and cultural competence [6]. Professional competence is considered a continuum that may increase or decrease over time, depending on various factors [8]. Improving the competencies of nurses across these dimensions will lead to various achievements, including the professional socialization and professionalization of nurses, as well as the provision of high-quality services to patients [4, 9, 10].

Different country-specific definitions of competence have been provided, depending on the context of each country [11]. This has resulted in ambiguity and complexity regarding the concept, as well as the absence of a uniform definition of competence [12, 13]. The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines competence as having sufficient knowledge, skills, judgment, and ability to carry out a particular task or function [13]. Gunawan and Aungsuroch refer to competence as a set of knowledge, attitudes, and skills that are manifested through behavior [14]. According to Fukada, competence is a behavioral trait and an acquisition of skills that results from experience and learning. It is achieved by the individual based on their attitudes and motivations, and by utilizing their individual interests and experiences [4]. DeGrande et al. define professional competence as the ability to make clinical decisions in accordance with clinical circumstances and based on prior experience [15].

Numerous studies show that there are significant differences and discrepancies in the implementation of standards and dimensions of nurse competencies, as well as the factors that influence them. Halcomb et al. listed clinical performance, professionalism, communication, and improving patient health as standards of competence for nurses [16]. According to the study by Valizadeh et al., the concept of competence is based on knowledge, attitude, skills, motivation, experience, creativity, responsibility, holistic care, ethical action, clinical judgment, communication with patients, cooperation and teamwork, management and leadership, perseverance and stability, and the ability to cope with difficult and complex situations [7]. In the study by DeGrande et al., the main dimensions of a nurse’s competence are described as situation management, teamwork, and decision-making [15]. In the study conducted by Smith, the integration of knowledge and practice, critical thinking, motivation, experience, skill, environment, communication, and professionalism are introduced :as char:acteristics of nurse competence [17].

In the existing literature, various factors have been identified as influencing the development of nurses’ professional competencies and the support they receive. The competence of nurses is affected by several factors, such as individual characteristics, educational level, work experience, professionalism, the type of environment in which they work, and critical thinking [18]. Tabari Khomeiran et al. report individual characteristics, motivation, theoretical knowledge, opportunities, experience, and environment as personal and non-personal factors that influence the development of nurses’ professional competencies [8]. In a study by Gunawan et al., age, marital status, educational level, specialized knowledge, clinical experience, job satisfaction, employment status, job position, income, burnout, and continuing education are identified as factors influencing clinical competence in nurses [11]. Nehrir et al. report other factors, such as knowledge, personal experiences, professional skills, motivation, decision-making power, self-confidence, professional independence, and positive social interactions as factors affecting nurses’ competence [6].

Nurses face a number of professional competency needs during their careers [19]. If these needs are not addressed and met, many nurses will leave the profession [19]; if these nurses are retained in the health system, the quality of care will deteriorate, and public health will be compromised [5]. Therefore, it appears necessary to focus on the standards of professional competence for nurses. Different standards have been implemented in various organizations; however, given the context-dependent nature of standards of professional competence, a systematic review is needed. This is because no comprehensive study has been found that reviews these standards based on existing literature, scientific articles, and the guidelines of national and international nursing organizations. Consequently, we decided to conduct a systematic review of the literature and nursing organizations’ guidelines to determine the competence standards for nurses. The results are expected to further develop the professional competencies of nurses, improve the quality of care, increase patient satisfaction, and promote the health of individuals in society.

Information and Methods

This systematic review of nursing professional competence standards was conducted based on the available scientific literature in Iran and worldwide, with the aim of reviewing the standards of nursing professional competence in 2023. Databases, such as the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and the Cochrane Library were consulted to determine the standards of competence for nurses and to confirm that the study was not duplicative [20].

Guidance, such as the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement is used in the preparation of the study protocol [20, 21]. Following the development of the protocol, the standards were reviewed based on the PRISMA 2020 statement to identify the standards of competence for nurses.

To ensure that the articles are fully covered, simultaneous searches of the databases PubMed, MEDLINE, and Embase are required [22, 23]. Researchers examined external databases, such as PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane, ProQuest, and the Web of Science. Google Scholar was also reviewed to ensure that the search is comprehensive. Additionally, internal databases, such as SID, IranMedex, IranDoc, and Magiran were searched.

A national nursing organization is a professional entity that coordinates, exchanges ideas, promotes, stimulates, educates, researches, and organizes scientific activities while providing human resources through policy development, legislation, and standardization. The International Council of Nurses is a large, global organization of nurses that influences nursing practice by setting standards and communicating procedures [24].

The keywords were selected from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), synonyms in various databases, and related free terms by two researchers. Studies on the competence of nurses were also examined to identify keywords relevant to this issue [20, 25].

Searches were performed in the title, abstract, and keywords in foreign databases using Population or Problem, Intervention or Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design (PICOS) and Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research Type (SPIDER) [26]. Additionally, the search was also conducted in Persian databases using translations of the aforementioned keywords in Persian and the same search strategy (Table 1).

Table 1. Review of professional competence standards for nurses using PICOS and SPIDER search strategies

Syntaxes were

developed and utilized to search both Iranian and foreign databases comprehensively and accurately, based on search strategies specific to each database (Table 2).

Table 2. Internal and external database syntaxes

The inclusion criteria were Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method articles that contain at least one of the professional competence standards for nurses in the title, keywords, or abstract of the article, scientific articles that have been published in peer-reviewed journals, articles from Iranian and foreign conferences that include at least one of the professional competence standards for nurses in the title, keywords, or abstract, guidelines and reports from reputable Iranian and international nursing organizations that feature at least one of the professional competence standards for nurses, and scientific articles, conference papers, guidelines, and reports that are relevant to the research question. Since the oldest article mentioning the competence standards for nurses was Davey’s article in 1995 [27], studies published from 1995 onwards were included in the study. A study was excluded if there was a lack of access to the full article due to unresolved journal access constraints.

The search results were compiled into a comprehensive list of articles, guidelines, and reports related to the research question. For better management of the results, references were stored in Mendeley Reference Management Software (version 1.19.8, 2008-2020, Mendeley Ltd) to facilitate the identification and removal of duplicate articles, guidelines, and reports [20].

After managing the search results and removing duplicate sources, the results were screened to identify resources related to the research question that met the inclusion criteria for studies. Accordingly, the titles and abstracts were first reviewed by two researchers, and in cases of disagreement, a third researcher was consulted. The screening occurred in two stages. First, sources were screened and briefly reviewed to identify potentially relevant materials. The full text of these potentially relevant sources was downloaded and printed before the complete study of the sources was conducted and the selection of those meeting the inclusion criteria was finalized. Following the screening, sources were selected to help establish the standards of professional competence for nurses [20].

The quality of quantitative articles was assessed using the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) checklist, qualitative articles were assessed with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist, and mixed-method articles were evaluated using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) [28-30].

A list of characteristics of the sources and the number of imported and exported resources was prepared to facilitate future revisions [20]. In this regard, a flowchart was developed based on the PRISMA 2020 statement to illustrate the number of imported and exported resources [28].

After screening the search results, a data extraction process was carried out. The researcher accomplished this by creating a table for data extraction [20]. The data extraction table for the articles contained the title of the study, the purpose, the authors, the year of publication, the location of the study, the data collection methods and tools, the study sample, and the results related to the proficiency standards for nurses. Additionally, given the type of available data on Iranian and international nursing organizations, the proposed form included information, such as the name of the organization, the year of publication, and the results concerning the standards of nursing competence.

The obtained findings were pooled after data extraction [20]. In this regard, a data extraction table was completed for each resource. Then, the tables were set up in Microsoft Word Professional Plus 2016 (16.0.17126.20132). Each of the extracted resources, which had been entered in the aggregated forms, was then recorded in one form for scientific articles and another form for nursing organizations. After categorizing the extracted information, the standards of competence for nurses were determined.

Findings

A total of 2,078 documents were initially received from scientific articles and from Iranian and international nursing organizations. After removing duplicate documents using Mendeley software, 1,619 documents remained. The researchers selected 52 documents relevant to the study objectives by examining the remaining documents and abstracts. Due to the lack of full text for two articles, the systematic review of the standards of competence for nurses ultimately covered 50 eligible documents, including 16 articles, 2 national nursing organizations, and 32 international nursing organizations (Figure 1) [31].

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews, which included searches of databases and registers only.

The obtained findings were synthesized after screening and assessing the quality of the documentation. A thematic synthesis approach was used for the data synthesis. From the examination of the 50 included documents, a total of 428 standards of competence for nurses were identified. Of these, 136 professional competence standards for nurses were extracted from 16 scientific articles (Table 3).

Table 3. Professional competence standards for nurses via scientific articles

Fifteen standards were identified from two national nursing organizations (Table 4).

Table 4. Professional competence standards for nurses via the Iranian national nursing organizations

Also, 277 standards were identified from 32 international nursing organizations (Table 5).

Table 5. Professional competence standards for nurses via international nursing organizations

Following the synthesis of the findings from the systematic review, comparable standards were compared and consolidated, which were then grouped and organized into domains. The synthesis of the studies led to the identification of five domains of professional competence standards for nurses, which included clinical competence, educational and research competence, ethical competence, communication and interpersonal competence, and management and leadership competence (Table 6).

Table 6. Domains and identified standards of nursing professional competence

Clinical competence

Clinical competence is often regarded as one of the most basic and fundamental professional competencies for nurses. The ability of nurses to perform various technical skills has always been considered one of the elements essential for developing competent nurses, and the application of nursing knowledge has been an important factor in enhancing their clinical competence. Nurses should acquire clinical skills and pay attention to clinical guidelines to provide effective services. Moreover, proficiency in working with hospital information systems (HIS) is considered a prerequisite for nurses to achieve clinical competence. Standards, such as a focus on decision-making, clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and problem-solving have been introduced as key elements of clinical competence.

Educational and research competence

In addition to strengthening the clinical competencies of nurses, the central elements of this competence area include enhancing patient care knowledge and utilizing theoretical knowledge, evidence-based practices, and the nursing process in the clinical setting. By regularly reviewing theoretical knowledge and applying evidence-based practices along with the nursing process, nurses can help consolidate their knowledge and prevent forgetting. The completion of this competence involves considering teaching and learning in universities, including employing experienced professors, utilizing effective teaching methods, and increasing the quantity and quality of clinical training. In addition to providing care, nurses play an important role in delivering education based on patient demands and those of the patient’s companions. Familiarity with scientific research and participation in research activities are essential for nurses to acquire research competencies.

Ethical competence

In addition to the need for nurses to possess clinical knowledge and skills, it is also important to pay attention to ethical values when caring for patients. Focusing on the patient as the center of care will help achieve competence. In this regard, adherence to ethical principles, such as fairness and justice in care, conscientiousness in caregiving, and the promotion of professional responsibility, are considered key factors in the ethical competence of nurses. Moreover, honoring the patient, self-regulation, and attention to the legal components of the profession are effective in achieving this competence.

Communication and interpersonal competence

Improving professional communication is a crucial aspect of nurses’ competence and encompasses various dimensions, including relationships between nurses and their colleagues, doctors, patients, and patients’ families. We identified communication and interpersonal relationships within the care team as one of the key factors in achieving competence and providing quality care. In this regard, enhancing professional communication and teamwork is essential for ensuring this competence. Nurses will be able to develop their teamwork skills by acquiring professional communication skills. In addition to developing communication and teamwork abilities, it is essential for organizations to promote teamwork and cultivate a supportive culture. In this context, members of the health team must be fully aware of their job descriptions and act accordingly.

Management and leadership competence

The competencies introduced are not sufficient on their own and that a focus on management and leadership competencies is important. Factors such as improving the orientation period for nurses, reviewing the staff training program, evaluating the methods of providing feedback to nurses, ensuring access to hospital facilities and equipment, and promoting specialization are some of the areas that health managers and leaders can focus on to ensure that nurses are adequately supported and trained.

Discussion

This study was conducted to establish professional competence standards for nurses. The findings were obtained through a systematic review of the literature and guidelines from nursing organizations. Five domains of competence were identified, comprising 25 standards. For nurses, four, seven, seven, two, and five standards of professional competence were identified in the five domains, including clinical, educational and research, ethical, communication and interpersonal, and management and leadership.

Clinical competence was one of the identified domains in the systematic review. The four standards identified within the clinical competence domain included acquiring clinical skills, adhering to clinical guidelines, developing skills in working with HISs, and focusing on decision-making, clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and problem-solving.

Nurses can provide high-quality and safe care to patients by relying on their clinical knowledge [80]. Our study demonstrated that attention to clinical skills and guidelines is recognized as one of the professional competencies of nurses. Several studies included in the review confirmed the results of this study, such as the research conducted by Ha & Nuntaboot, identifying nursing skills and practice as new competencies required for nurses compared to the national nursing competence standards in Vietnam [36].

Halcomb et al. report professional practice and nursing care as the professional standards of practice for nurses in Australia [43]. In other studies and nursing organizations, clinical practice and skills have been reported as one of the competencies for nurses [16, 67]. The acquisition of skills for working with HISs was identified as an additional clinical competence standard, in line with the findings of the study recognizing information technology knowledge and skills as a competence standard [16, 43].

This is important for accessing patient clinical records, providing diagnostic and therapeutic services, and monitoring patient treatment. The computer literacy of nurses is a prerequisite for gaining competence and delivering quality, cost-effective care [81]. Other clinical competence standards included the reinforcement of decision-making, clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and problem-solving. Some studies have shown that clinical decision-making is one of the competencies essential for clinical performance in nursing care [32]. Clinical reasoning and critical thinking [35, 42] are also vital for the training and competence of nurses. According to Halcomb et al., problem-solving is recognized as one of the nursing competence standards in primary care [16]. This finding aligns with international guidelines, such as those from the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, which emphasize critical thinking and analysis of nursing performance as essential nursing competence standards [59].

One of the domains most frequently addressed in our systematic review was educational and research competence. This domain consisted of seven identified standards: enhancing patient care knowledge, using theoretical knowledge, applying evidence-based practices and the nursing process in the clinical setting, employing experienced professors, utilizing effective teaching methods, increasing the quantity and quality of clinical training, providing education based on patient demands and those of the patient’s companions, and fostering familiarity with scientific research and participation in research activities.

Some studies included indicated that improving the competencies of nurses requires knowledge acquisition [35, 36]. Once knowledge is acquired, the application of theoretical knowledge, scientific evidence, and the nursing process in clinical practice may enhance educational and research competence. Several studies have shown that the use of evidence-based practice is effective in improving nursing competence, corroborating the results of our study [32, 39, 44, 45]. This finding aligns with the emphasis placed by the American Nurses Association on the importance of evidence-based practice in nursing [72]. In accordance with the findings of this study, the nursing process is established as an important standard of competence for nurses by Lee et al. [39]. University professors play a crucial role in qualifying nurses through their training. Professors are responsible for teaching nursing students and preparing them for future careers in healthcare. To acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for providing quality care, it is essential that teaching institutions, especially professors, recognize the significance of their work in training professionals and develop the attitudes and skills needed for success.

Clinical educators must possess characteristics, such as effective communication with students, professional skills, evaluation skills, teaching abilities, and personal attributes for teaching. Therefore, it is essential for professors to evaluate their teaching and improve their practice by identifying aspects of their instruction that are incomplete [82]. Baker et al. report the curriculum, learning experiences, faculty, instructors, mentors, and educational resources as standards for the competence of nurses [35]. Supporting these findings, teaching and learning have been shown to be effective in the development of competence [16, 41]. Need-based education for patients and their families is another standard introduced in the study by Dung et al. as a component of nurse competence [33], and this is consistent with our results. In addition to educational competence, research competence is also a requirement for nurses’ professional competence. In this respect, the studies reviewed indicate that scientific inquiry and research are among the standards of competence for nurses [34, 41], which is confirmed by the results of this study.

Ethical competence is considered an important domain of professional competence for nurses. In the ethical competence domain, seven identified standards include adherence to ethical principles, fairness and justice in care, conscientiousness in care, promoting professional responsibility, honoring patients, self-regulation, and attention to the legal components of the profession.

It is necessary for nurses to acquire professional competencies through ethical and legal competence [36] and ethical practice [39, 40]. The College of Nurses of Ontario also considers ethics to be a standard of competence [56]. Bickford identifies fair practice as one of the competence standards for nurses in the field of nursing [34]. In another study, the promotion of equity by nurses was based on standards derived from a systematic review of several international organizations [45]. Ethical conscientious accountability was another standard that the Republic of the Philippines Professional Regulation Commission deemed important [76], and our study’s results reinforce this.

Another frequently cited standard is responsibility. The International Labour Organization and the Professional Regulatory Board of Nursing are among the nursing organizations that consider this standard essential [66, 70], supporting our results. It was found that honoring patients was effective in ensuring the ethical competence of nurses. Consistent with our findings, patient advocacy has been identified as a standard competence for nurses [34]. The Nursing and Midwifery Council also considers that prioritizing patients through identifying their demands, demonstrating respectful behavior, and upholding patients’ rights is an effective way to develop competent nurses [65]. Self-regulation of nurses is another factor in promoting professional competence, a result confirmed by several studies included in the review [53, 58, 68].

Improving professional communication and enhancing teamwork were two standards in the domain of communication and interpersonal competence. A study by Parnikh et al. has shown a positive and significant relationship between professional communication and professional engagement, as well as interest in one’s job, leading to quality care and patient safety [83]. Improving professional communication aligns with the guidelines for nurses, which consider this standard an integral part of nursing competencies [46, 47]. Regarding teamwork enhancement, studies highlight the importance of focusing on teamwork as one of the key standards for improving nurses’ competencies [40, 43]. Therefore, strengthening communication and teamwork skills should be prioritized in the training of nurses.

Finally, in the domain of management and leadership competence, five standards were identified: improving the orientation period for nurses, reviewing the staff training program, assessing the methods of providing feedback to nurses, ensuring the availability of hospital facilities and equipment, and promoting specialization.

Improving in-service training was another standard identified as a prerequisite for enhancing professional aptitude. Supporting the findings of this study, Sato & Ishimaru argue that in-service training is necessary to improve nurses’ competencies [84]. The training provided should be tailored to the educational needs of nurses. These needs can be assessed through an analysis of educational requirements [85]. Indiana University Southeast also considers that the training of nurses is a factor in improving their competence [50], which aligns with our results.

Another standard identified was the review of the methods used to provide feedback to nurses. Feedback is a crucial component of nursing. If nurses do not receive feedback about their performance, they may assume they do not need to improve in any area. Therefore, nursing specialists should consider feedback as part of their learning process and monitor how they receive it. Feedback is most effective when provided in a supportive environment and on a regular basis. Nursing managers should ensure that they offer feedback in a timely manner and focus on specific aspects of an individual’s performance. This type of feedback is considered very valuable and useful, enabling individuals to assess their own skills and enhancing motivation, self-confidence, self-esteem, and abilities [86].

Providing hospital facilities and equipment is considered a standard of nursing competence. Maphumulo & Bhengu also emphasize the importance of facilities and physical infrastructure, in accordance with this study [38]. The physical environment, including the design and performance of hospital buildings, had a significant influence on nurses’ recruitment and retention. Available facilities can have a substantial impact on nurses’ performance and the quality of care provided to patients [87].

Our findings serve as a reliable source of information for nurses and the nursing management system regarding the standards of nursing competence. Attention has been given to some of the standards of professional competence for nurses. By considering these domains, managers can effectively address the needs for nurses’ professional competencies, train competent nurses, and improve the quality of healthcare.

Conclusion

Clinical competence, educational and research competence, ethical competence, communication and interpersonal competence, and management and leadership competence are five domains of competence based on articles and guidelines from nursing organizations.

Acknowledgments: We express our gratitude to the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The current study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.SUMS.NUMIMG.REC.1400.033, approval date: 2021.15.09).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors' Contribution: Zarshenas L (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Mehri Z (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Rakhshan M (Third Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Khademian Z (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Mehrabi M (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%); Jamshidi Z (Sixth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (10%)

Funding/Support: This study was financially supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Keywords:

References

1. WHO. Nursing and midwifery in the history of the World Health Organization (1948-2017). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Link]

2. Health Resources and Services Administration. The future of the nursing workforce: National- and state-level projections, 2012-2025. Rockville. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Link]

3. AACN. Nursing fact sheet [Internet]. Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges of Nursing; 2019 [cited 2024 May 20]. Available from: https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-data/fact-sheets/nursing-shortage. [Link]

4. Fukada M. Nursing competency: Definition, structure and development. Yonago Acta Med. 2018;61(1):1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.33160/yam.2018.03.001]

5. Karami A, Farokhzadian J, Foroughameri G. Nurses' professional competency and organizational commitment: Is it important for human resource management?. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e187863. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0187863]

6. Nehrir B, Vanaki Z, Mokhtari Nouri J, Khademolhosseini SM, Ebadi A. Competency in nursing students: A systematic review. Int J Travel Med Glob Health. 2016;4(1):3-11. [Link] [DOI:10.20286/ijtmgh-04013]

7. Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Eskandari M, Alizadeh S. Professional competence in nursing: A hybrid concept analysis. Med Surg Nurs J. 2019;8(2):e90580. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/msnj.90580]

8. Tabari Khomeiran R, Yekta ZP, Kiger AM, Ahmadi F. Professional competence: Factors described by nurses as influencing their development. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53(1):66-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2006.00432.x]

9. Pai HC, Huang YL, Cheng HH, Yen WJ, Lu YC. Modeling the relationship between nursing competence and professional socialization of novice nursing students using a latent growth curve analysis. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020;49:102916. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102916]

10. Mehri Z, Zarshenas L, Rakhshan M, Khademian Z, Mehrabi M, Jamshidi Z. Novice nurses' professional competence: A qualitative content analysis. J Educ Health Promot. 2025;14(1):17. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1819_23]

11. Gunawan J, Aungsuroch Y, Fisher ML, Marzill C, Liu Y. Factors related to the clinical competence of registered nurses: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(6):623-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jnu.12594]

12. Garside JR, Nhemachen JZZ. A concept analysis of competence and its transition in nursing. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(5):541-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2011.12.007]

13. Merriam-Webster. Competence. Springfield: Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online; 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/competence?src=search-dict-box. [Link]

14. Gunawan J, Aungsuroch Y. Managerial competence of first‐line nurse managers: A concept analysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2017;23(1):e12502. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/ijn.12502]

15. DeGrande H, Liu F, Greene P, Stankus JA. Developing professional competence among critical care nurses: An integrative review of literature. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;49:65-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2018.07.008]

16. Halcomb E, Stephens M, Bryce J, Foley E, Ashley C. Nursing competency standards in primary health care: An integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(9-10):1193-205. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jocn.13224]

17. Smith SA. Nurse competence: A concept analysis. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2012;23(3):172-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.2047-3095.2012.01225.x]

18. Rizany I, Hariyati R, Handayani H. Factors that affect the development of nurses' competencies: A systematic review. ENFERMERÍA CLÍNICA. 2018;28(Suppl 1):154-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1130-8621(18)30057-3]

19. Almada P, Carafoli K, Flattery JB, French DA, McNamara M. Improving the retention rate of newly graduated nurses. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2004;20(6):268-273. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00124645-200411000-00006]

20. Denison HJ, Dodds RM, Ntani G, Cooper R, Cooper C, Sayer AA, et al. How to get started with a systematic review in epidemiology: An introductory guide for early career researchers. Arch Public Health. 2013;71(1):21. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/0778-7367-71-21]

21. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097]

22. Woods D, Trewheellar K. Medline and embase complement each other in literature searches. BMJ. 1998;316(7138):1166. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.316.7138.1166]

23. Lawrence DW. What is lost when searching only one literature database for articles relevant to injury prevention and safety promotion?. Inj Prev. 2008;14(6):401-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/ip.2008.019430]

24. Nehrir B, Vanaki Z, Mokhtari Nouri J, Khademolhosseini SM, Ebadi A. Competency in nursing students: a systematic review. Int J Travel Med Glob Health. 2016;4(1):3-11.. [Link] [DOI:10.20286/ijtmgh-04013]

25. Haghdoust A, Sadeghirad B. Systematic review and meta-analysis. 4th ed. Tehran: Gap; 2017. [Persian] [Link]

26. Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):579. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0]

27. Davey GD. Developing competency standards for occupational health nurses in Australia. AAOHN J. 1995;43(3):138-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/216507999504300304]

28. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.b2700]

29. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042]

30. Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285-91. [Link] [DOI:10.3233/EFI-180221]

31. PRISMA flow diagram [Internet]. Greenville: PRISMA Executive; 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram. [Link]

32. Sakuramoto H, Kuribara T, Ouchi A, Haruna J, Unoki T, et al. Clinical practice competencies for standard critical care nursing: Consensus statement based on a systematic review and Delphi survey. BMJ Open. 2023;13(1):e068734. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068734]

33. Dung PT, Hung DK, Cuong BM, Trang LTT. Nurses' knowledge, practice and confidence about wound care based on the competency standards in 8 hospitals in Vietnam. J Clin Images Med Case Rep. 2021;2(5):1364. [Link] [DOI:10.52768/2766-7820/1364]

34. Bickford CJ. Updated nursing scope and standards. Foundational document reflects changes in healthcare. Maryland: American Nurses Association; 2021. [Link]

35. Baker C, Cary AH, Da Conceicao Bento M. Global standards for professional nursing education: The time is now. J Prof Nurs. 2021;37(1):86-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.10.001]

36. Ha DT, Nuntaboot K. New competencies required for nurses as compared to the national nursing competency standards in Vietnam. KONTAKT. 2020;22(2):92-5. [Link] [DOI:10.32725/kont.2020.016]

37. Tønnessen S, Scott A, Nortvedt P. Safe and competent nursing care: An argument for a minimum standard?. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(6):1396-407. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0969733020919137]

38. Maphumulo WT, Bhengu BR. Perceptions of professional nurses regarding the national core standards tool in tertiary hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal. Curationis. 2020;43(1):1971. [Link] [DOI:10.4102/curationis.v43i1.1971]

39. Lee H, Kim DJ, Han JW. Developing nursing standard guidelines for nurses in a neonatal intensive care unit: A delphi study. Healthcare. 2020;8(3):320. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare8030320]

40. Usui M, Yamauchi T. Guiding patients to appropriate care: Developing Japanese outpatient triage nurse competencies. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2019;81(4):597-612. [Link]

41. Salem OA, Aboshaiqah AE, Mubaraki MA, Pandaan IN. Competency based nursing curriculum: Establishing the standards for nursing competencies in higher education. Open Access Libr J. 2018;5(11):1-8. [Link] [DOI:10.4236/oalib.1104952]

42. Cashin A, Heartfield M, Bryce J, Devey L, Buckley T, Cox D, et al. Standards for practice for registered nurses in Australia. Collegian. 2017;24(3):255-66. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.colegn.2016.03.002]

43. Halcomb E, Stephens M, Bryce J, Foley E, Ashley C. The development of professional practice standards for Australian general practice nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(8):1958-69. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jan.13274]

44. Douglas MK, Rosenkoetter M, Pacquiao DF, Callister LC, Hattar-Pollara M, Lauderdale J, et al. Guidelines for implementing culturally competent nursing care. J Transcult Nurs. 2014;25(2):109-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1043659614520998]

45. Douglas MK, Pierce JU, Rosenkoetter M, Pacquiao D, Callister LC, Hattar-Pollara M, et al. Standards of practice for culturally competent nursing care: 2011 update. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22(4):317-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1043659611412965]

46. Deputy for nursing, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Ministry of Health. Professional Nursing Care Standards. 2020. [Link]

47. Iranian Nursing Organization. Nursing service standards. Tehran: Iranian Nursing Organization; 2010. [Link]

48. Palliative Care Nurses Australia. The competency standards for specialist palliative care nursing practice comprise five domains. Brisbane: Palliative Care Nurses Australia; 2022. [Link]

49. Nurses Association of New Brunswick. Standards of practice for registered nurses. Fredericton: Nurses Association of New Brunswick; 2022. [Link]

50. Indiana University Southeast. Standards of professional performance. New Albany: Indiana University Southeast; 2022. [Link] [DOI:10.2979/13126.0]

51. BCCNM. Professional standards for registered nurses and nurse practitioners. Vancouver: British Columbia College of Nurses and Midwives; 2020. [Link]

52. Helene Fuld College of Nursing (HFCN). Helene Fuld College of Nursing technical standards for core professional nursing competency performance. New York: Helene Fuld College of Nursing; 2020. [Link]

53. Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association (SRNA). Registered nurse practice standards. Canada: Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association; 2019. [Link]

54. College of Registered Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador (CRNNL). Standards of practice for registered nurses and nurse practitioners. Mount Pearl: College of Registered Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador; 2019. [Link]

55. College of Registered Nurses of Prince Edward Island. Standards for nursing practice. Charlottetown: College of Registered Nurses of Prince Edward Island; 2018. [Link]

56. CNO. Professional standards, revised 2002. Toronto: College of Nurses of Ontario; 2018. [Link]

57. Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). Future nurse: Standards of proficiency for registered nurses. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council; 2018. [Link]

58. Nova Scotia College of Nursing (NSCN). Standards of practice for registered nurses. Canada: Nova Scotia College of Nursing; 2017. [Link]

59. NMBA. Registered nurse standards for practice. Melbourne: Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia; 2016. [Link]

60. Australian College of Children and Young People's Nurses (ACCYPN). The development of standards of practice for children and young people's nurses. Brisbane City: Australian College of Children and Young People's Nurses; 2016. [Link]

61. Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland. Nurse registration programmes standards and requirements. Dublin: Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland; 2016. [Link]

62. Hospital Services Department and Cambodian Council of Nurses. Guideline for the standard of nursing care, Cambodia. Cambodia: Cambodian Council of Nurses; 2015. [Link]

63. The Queen's Nursing Institute (QNI) and The Queen's Nursing Institute Scotland (QNIS). The QNI/QNIS voluntary standards for district nurse education and practice. London: The Queen's Nursing Institute; 2015. [Link]

64. American Nurses Association. Nursing: Scope and standards of practice. 3rd ed. Maryland: American Nurses Association; 2015. [Link]

65. Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). The code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council; 2015. [Link]

66. International Labour Organization (ILO). National nursing core competency standards-training modules for the Philippines. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2014. [Link]

67. Ministry of Health Brunei Darussalam. Core competency standards for registered nurses and midwives in Brunei Darussalam. Bandar Seri Begawan: Ministry of Health Brunei Darussalam; 2013. [Link]

68. College of Registered Nurses of Nova Scotia (CRNNS). Standards of practice for registered nurses. Canada: College of Registered Nurses of Nova Scotia; 2012. [Link]

69. New Zealand Nurses Organization. Standards of professional nursing practice. Wellington: New Zealand Nurses Organization; 2012. [Link]