Volume 6, Issue 4 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(4): 211-218 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2025/08/5 | Accepted: 2025/09/30 | Published: 2025/10/16

Received: 2025/08/5 | Accepted: 2025/09/30 | Published: 2025/10/16

How to cite this article

Sadat S, Shirazi F, Zoladl M, Koohpeyma M. Effect of Early and Gradual Ambulation on Postoperative Complications After Sleeve Gastrectomy. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (4) :211-218

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-445-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-445-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Student Research Committee, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- “Community Based Psychiatric Care Research Center” and “Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

3- “Social Determinants of Health Research Center” and “Department of Psychiatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- “Community Based Psychiatric Care Research Center” and “Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

3- “Social Determinants of Health Research Center” and “Department of Psychiatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (19 Views)

Introduction

Nowadays, the incidence of morbid obesity has increased worldwide and has become a global problem [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization, it is predicted that by 2030, almost 60% of the world’s population, or 3.3 billion individuals, may suffer from the effects of excessive weight gain [3]. In addition to life restrictions, obesity can lead to disorders such as cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, gastrointestinal issues, musculoskeletal problems, renal complications, neurological conditions, and various types of cancer [4, 5]. Obesity can be treated using a variety of techniques, including pharmacological methods, low-calorie diets, behavior modification, exercise, and surgery [6]. Evidence has indicated that non-surgical methods have not been effective in achieving weight reduction among individuals suffering from morbid obesity [7, 8]. Thus, there has been an increasing tendency to utilize surgical methods for weight reduction. Therefore, it is essential to select an appropriate surgical technique and take proper measures to minimize postoperative complications [9]. To date, there is a rising trend towards bariatric surgeries due to their long-term impacts on weight reduction. Studies have revealed the effectiveness of this surgical method in the treatment of obesity-related disorders [9, 10].

In recent years, bariatric surgeries have ranked second among abdominal surgeries [11]. One of the restrictive procedures in bariatric surgery is sleeve gastrectomy, in which the stomach volume is reduced to 100-150 cc by removing the greater curvature, causing the stomach to take on the shape of a tube. This method also results in a decline in the number of cells producing ghrelin (an appetite regulator), thereby reducing its serum level and helping to decrease obesity [12, 13]. Since 2014, sleeve gastrectomy has been the most common surgical operation for obesity treatment [2, 14]. Although this laparoscopic surgery is effective in weight reduction, it can be accompanied by both short- and long-term complications. The short-term complications of this surgery include pain, nausea, vomiting, and hemodynamic disorders [15, 16]. If these postoperative complications are not controlled and treated, they can increase the length of hospital stay and, consequently, the treatment costs [17].

Routine postoperative care includes bed rest until vital signs and consciousness stabilize. Nonetheless, some researchers believe that long-term bed rest in a supine position is recommended based on physicians’ opinions and experiences rather than scientific evidence [18]. On the other hand, prolonged immobility can increase the risk of numerous complications in the gastrointestinal, respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems, as well as skin issues. It can also lead to nausea, vomiting, chronic constipation, muscle pain, acute back pain, arterial thrombosis, and embolism [19]. Therefore, in some healthcare centers, patients who have undergone extensive surgical operations, including sleeve gastrectomy, are encouraged to engage in early ambulation [20]. Although early ambulation has been effective in reducing postoperative complications and the length of hospital stay [21], it has been accompanied by limitations and obstacles, including a lack of information among treatment teams and patients, as well as numerous attachments to the patient’s body [22]. Additionally, studies have shown a paucity of evidence-based information regarding this protocol, resulting in the continuation of conventional care.

Sleeve gastrectomy, despite being an effective and widely performed bariatric procedure, is often associated with postoperative complications such as pain, nausea, and vomiting. Early mobilization after surgery has been shown to improve recovery and reduce such complications in other types of surgery; however, evidence regarding the optimal timing and approach to ambulation after sleeve gastrectomy remains limited. Considering the growing number of surgical interventions for obesity treatment, there is an increasing need for low-risk strategies that can accelerate postoperative recovery and minimize complications such as pain and vomiting. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effects of early and gradual ambulation on postoperative complications after sleeve gastrectomy.

Instrument and Methods

Study design and participants

This single-center, parallel-group randomized clinical trial was conducted on morbidly obese patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy at the bariatric surgery ward of Ghadir Mother and Child Hospital in Shiraz, Iran from June to September 2016. According to the inclusion criteria, which included having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher and being within the age range of 18-55 years, and the exclusion criteria, which consisted of a history of mental disorders, respiratory disorders, morphine addiction, cigarette smoking, musculoskeletal disorders due to body positions during the operation, abnormal problems, such as vascular damage, removal of an excessive portion of the stomach, anastomotic leak, and inability to tolerate the study protocol, 132 eligible sleeve gastrectomy candidates were selected and allocated to the gradual ambulation (GA) group, early ambulation (EA) group, and control group using block randomization.

Based on the results of Asadi et al.’s study [23], considering α=0.01 and a power of 80%, along with a 15% loss rate, the sample size was estimated to be 44 eligible patients in each study group. Therefore, a total of 132 patients were enrolled in the research.

Participants were consecutively recruited from patients scheduled for elective sleeve gastrectomy. Random allocation was performed in a 1:1:1 ratio using a computer-generated randomization list with a block size of six. Allocation concealment was ensured by using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes prepared by a researcher not involved in enrollment or data collection. All participants provided written informed consent before surgery. Follow-up assessments were conducted during hospitalization and one week after surgery to evaluate postoperative complications and recovery outcomes.

Instrument

Data were collected using a demographic information form, a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), and a form for gathering information about the surgery and postoperative complications, including the length of operation and frequency of vomiting, among others. The demographic information form included the patients’ age, sex, education level, occupation, and marital status. The patients’ weight and height were also measured prior to the operation. After the operation, when the patients were discharged from the recovery room and admitted to the ward, another form was used to record information about the length of surgery, duration of stay in the recovery room, and frequency of vomiting.

Pain intensity was assessed using a VAS, which is a 10 cm ruler with the left end representing no pain and the right end representing the most severe pain. The patients were asked to mark their pain intensity on the ruler at different time points. Then, one of the researchers measured the patients’ pain intensity in centimeters and recorded it as the pain score, which could range from zero to ten [24]. The validity and reliability of the visual analogue scale have been demonstrated in numerous studies [25, 26].

The frequency of vomiting was recorded by the attending nurse during the same time intervals. Secondary observations included the presence of nausea, time to first mobilization, and length of hospital stay. All assessments were performed by a trained nurse who was blinded to group allocation.

Intervention

All ethical considerations were observed, and all necessary permissions for conducting the research were obtained from the relevant administrators. Written informed consent forms were also obtained from all participants.

Prior to the intervention, the participants were provided with the necessary explanations and asked to complete the demographic information form. In the GA group, gradual ambulation was carried out through the following process: the patients were placed in a supine position after entering the ward. During the first two hours, the head of the bed was raised by 15 degrees. During the third and fourth hours, the head of the bed was raised by 30 and 45 degrees, respectively. The head of the bed was then returned to 15 degrees during the fifth and sixth hours. Additionally, the patients were encouraged to move their bodies to the left and right. After that, they were asked to change the positions of their upper and lower extremities. In the seventh hour, the patients were placed in a sitting position for five minutes. They were then allowed to sit on the chairs next to their beds for 10-15 minutes. If the patients experienced no problems, they could walk with the help of their companions in the corridor. Following that, they were allowed to walk within the ward.

In the EA group, four hours after the patients’ entrance into the ward, their level of consciousness was assessed by a nurse. If the patients were fully conscious, they sat on the bed in the presence of the nurse for ten minutes. If there was no change in the patients’ level of consciousness, they were allowed to sit on the chairs next to their beds for five minutes. At this stage, the patients’ levels of consciousness and mental status were evaluated again. If the patients were in appropriate condition, they could walk 15 meters around their beds with the assistance of their companions. After two hours, the patients were asked to sit on the bed for five minutes and then on the chair for five minutes. If no problems occurred, they could walk in the corridor with the help of their companions for five minutes. During this stage, a nurse accompanied the patients to prevent falls. This process was repeated every four hours from 6 AM until 12 AM.

In the control group, the patients received routine care services. Depending on their mental status and willingness, and irrespective of time, they were encouraged to walk at least once on the first day and three times on the second day.

All interventions were supervised by a trained nurse who ensured patient safety, prevented falls, and documented adherence to the ambulation protocols. All patients across the three groups received identical postoperative analgesic and antiemetic regimens to control for medication-related effects. Environmental and surgical conditions were kept constant for all participants to minimize confounding factors.

The three groups were compared in terms of postoperative complications, including pain and frequency of vomiting, at five time points: upon entering the ward and immediately after, as well as at 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours after ambulation.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 21 software by a statistician who was blind to the study groups. Statistical comparisons were conducted using appropriate tests, such as chi-square, ANOVA, and repeated measures ANOVA.

Findings

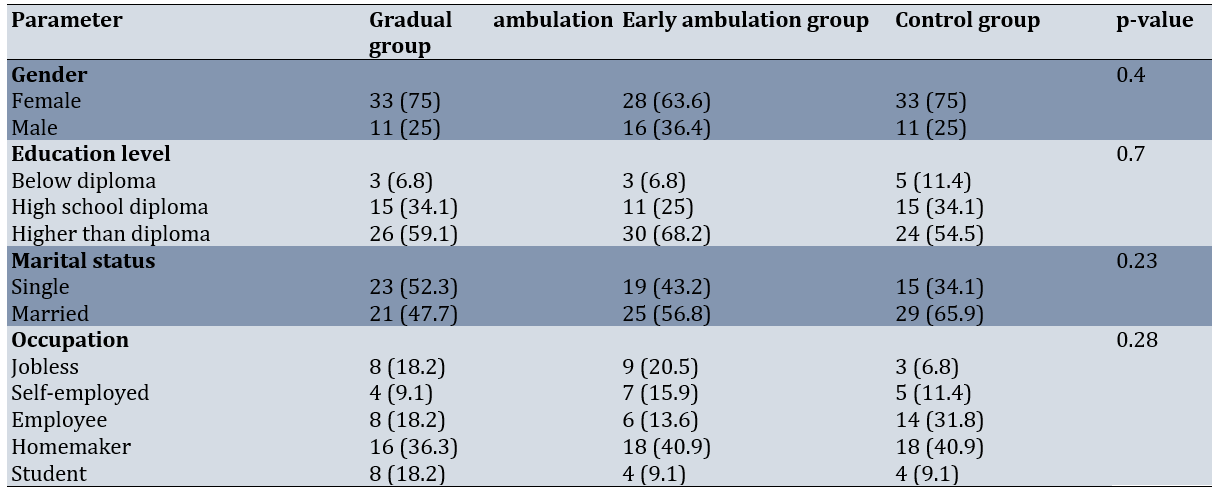

Among the 132 eligible sleeve gastrectomy candidates, 94 were female (71.2%) and 38 were male (28.8%). The majority of the study participants were married (75%), homemakers (39.4%), and held a degree higher than a diploma (60.6%). The mean age of the participants was 32.1±7.1 years, and their mean BMI was 44.4±8.6kg/m². The mean age of the participants was 31.1±7.4 years in the GA group, 31.2±6.1 years in the EA group, and 34.0±7.5 years in the control group (p-value=0.09). The mean BMI was 43.5±3.0kg/m²in the GA group, 45.6±4.3kg/m²in the EA group, and 45.3±5.9kg/m²in the control group (p-value=0.06). The mean duration of surgery was 150.3±38.9 minutes in the GA group, 155.8±29.3 minutes in the EA group, and 159.9±30.0 minutes in the control group (p-value=0.39). The mean duration of stay in the recovery room was 86.8±34.8 minutes in the GA group, 78.3±27.7 minutes in the EA group, and 92.7±36.2 minutes in the control group (p-value=0.1).The three groups were similar in terms of age, sex, marital status, education level, occupation, length of surgery, and length of stay in the recovery room (p>0.05; Table 1).

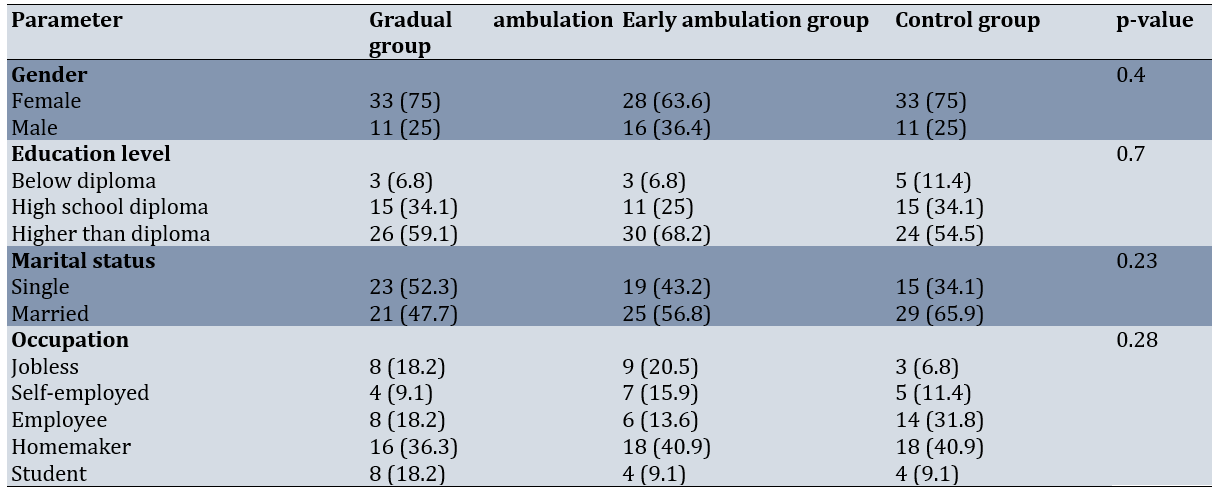

Table 1. Frequency of demographic data of the participants (n=44 per group)

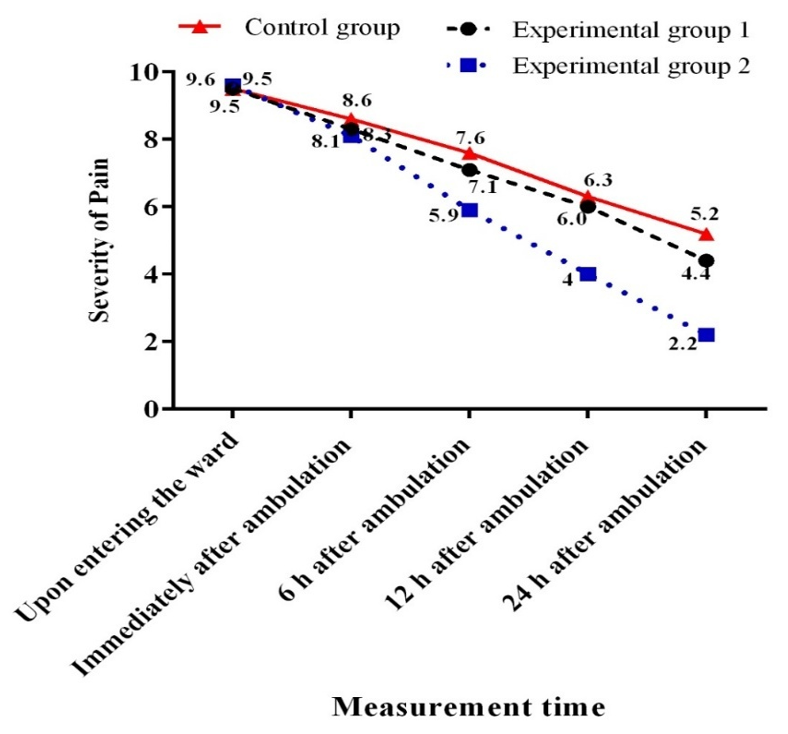

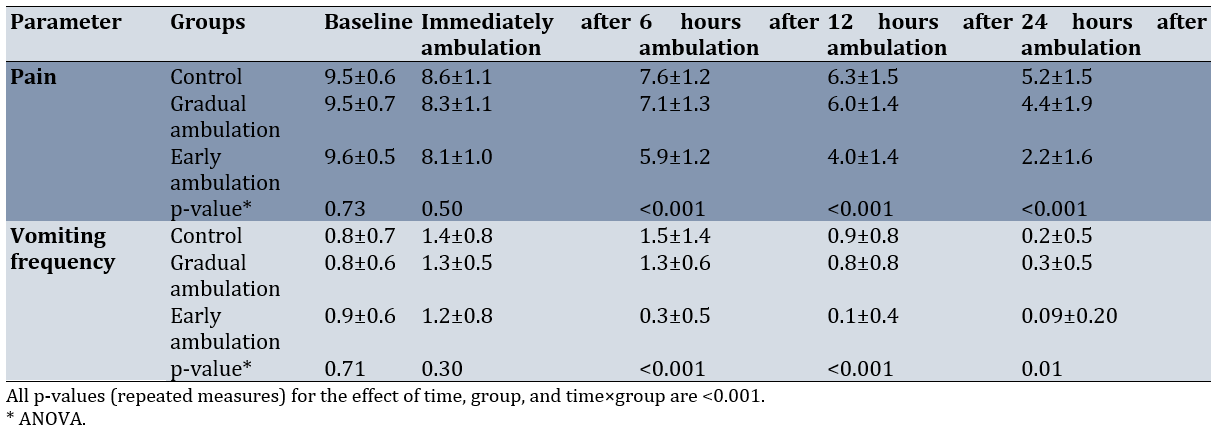

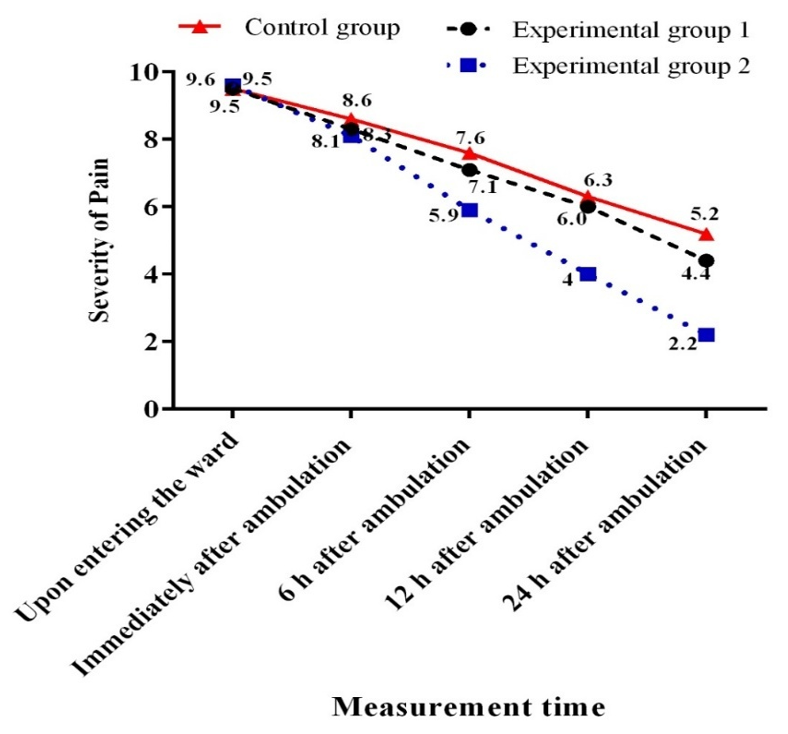

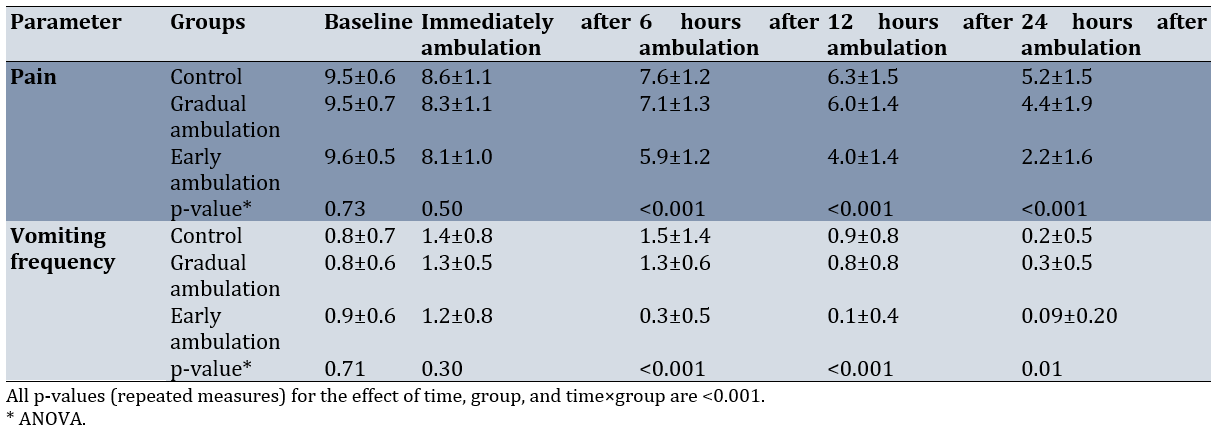

There was no significant difference among the three groups regarding the mean pain intensity at baseline (p=0.73). However, there was a significant reduction in pain intensity in the three groups over time (p<0.001; Figure 1). Moreover, between-group comparisons indicated no significant difference among the three groups concerning pain intensity at baseline and immediately after ambulation. However, significant differences were observed in this regard at 6, 12, and 24 hours after ambulation. The Bonferroni post-hoc test showed that the mean intensity of pain was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the GA (p<0.001) and control (p<0.001) groups. Nonetheless, the GA group did not show a significant difference from the control group in this respect. Furthermore, significant differences were detected between both intervention groups and the control group concerning the mean intensity of pain 24 hours after ambulation (p=0.036 for the GA group and p<0.001 for the EA group). Additionally, the mean intensity of pain was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the GA group (p<0.001).

Figure 1. Mean changes in the severity of patients’ pain in terms of measurement time.

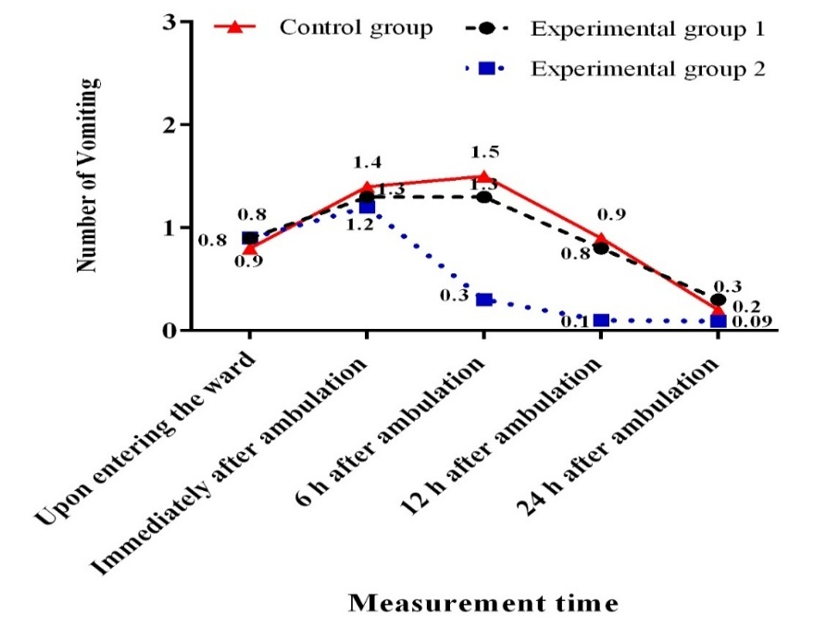

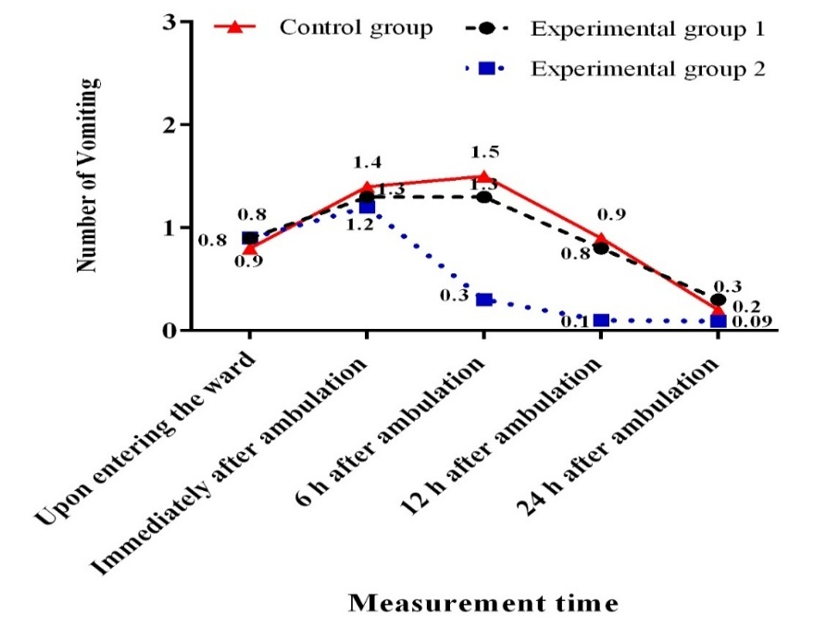

There was no significant difference among the three groups regarding the frequency of vomiting at baseline and immediately after ambulation. However, a significant difference was observed among the three groups in this regard at 6, 12, and 24 hours after ambulation (p<0.05; Figure 2). The frequency of vomiting was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the GA (p<0.001) and control (p<0.001) groups six hours after ambulation. However, the GA group did not show a significant difference from the control group in this respect. After 12 hours, the frequency of vomiting was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the GA (p=0.001) and control (p<0.001) groups. Nonetheless, no significant difference was found between the GA and control groups in this regard. After 24 hours, the frequency of vomiting was significantly lower in the EA group than in the GA group (p=0.01), but there was no significant difference from the control group (p=0.1; Table 2).

Figure 2. Mean changes in patients' vomiting frequency in terms of measurement time.

Table 2. Comparisons of mean changes in complications at five measurement points

Discussion

This research aimed to determine the effect of early and gradual ambulation on postoperative complications after sleeve gastrectomy. Compared to GA and the conventional method, EA was effective in reducing the intensity of pain and the frequency of vomiting at 6, 12, and 24 hours after the operation. Similarly, Lee et al. conducted a study on 100 patients undergoing colon surgery in South Korea in 2011 and found that, compared to conventional care, early ambulation in the form of a rehabilitation program can decrease complications, as well as the time required for patients to return to their daily activities [27].

There was a decline in the mean intensity of pain in all three groups. Between-group comparisons indicated a more pronounced decrease in the early ambulation group compared to both the control group and the gradual ambulation group after six hours. Although a significant difference was observed between the gradual ambulation group and the control group at some time points, the decrease was most prominent in the early ambulation group. Similarly, Drolet et al. conducted a study in California in 2013 and concluded that ambulation results in a decrease in pain as well as the need for sedative drugs, leading to earlier discharge of patients from the ICU [28]. Alaa Eldin et al. showed that GA reduces pain among patients undergoing angiography [29]. In contrast, Vosouqian et al. stated that EA has no effect on the reduction of headache among patients undergoing cesarean sections [30]. After laparoscopic surgeries, pain usually results from phrenic nerve stimulation, the entry of laparoscopic gas into the peritoneum, and surgical incisions [31], which plays a critical role in increasing the length of hospital stay and treatment costs. In this context, some studies have indicated that rehabilitation and movement are more effective in reducing postoperative pain intensity compared to the size of surgical incisions [32, 33]. Walking after the operation may enhance the absorption of laparoscopic gases, thereby decreasing the intensity of abdominal pain [34].

Another complication investigated was the frequency of vomiting. This phenomenon is prevalent after bariatric surgeries due to the use of anesthesia medications, manipulation of the gastrointestinal system, and the utilization of laparoscopic gases. Major et al. conducted a study in 2018 and revealed that the prevalence of vomiting is higher in sleeve gastrectomy than in other bariatric surgeries [35]. Studies have also shown that two-thirds of the patients undergoing bariatric surgeries experience postoperative nausea and vomiting [36]. EA could significantly reduce the frequency of vomiting compared to gradual ambulation and routine care. In the same vein, Deng et al. showed that implementing an abdominal-based early progressive mobilization program in critically ill, intubated patients significantly improves gastric motility and reduces complications of feeding intolerance, including vomiting, abdominal distention, and diarrhea [37]. Fathi et al. also reported that placing chemotherapy patients in a half-seated position reduces the frequency of vomiting [38]. On the contrary, the review study conducted by Seok et al. indicated that movement after surgical operations leads to the incidence of nausea and vomiting [39]. Yet, scientific evidence has shown that ambulation and increased activity can enhance peristalsis, which might reduce nausea and vomiting.

Overall, EA decreased postoperative complications among patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. Considering the increasing population of obese individuals and the resultant rise in the need for bariatric surgeries, preventing the complications of these operations is of utmost importance. The prevention of vomiting and pain is also crucial from the patients’ perspectives, as these complications can delay their discharge and increase their treatment costs. A strong point of the present study was the relative similarity of the patients and the uniform care conditions for all patients in a single ward. However, one of the uncontrollable limitations of the study was the presence of individual differences in surgical operations and anesthesia procedures. Another limitation was related to laparoscopic surgery; in fact, different laparoscopic gas pressures are used for various individuals, which can influence the incidence of postoperative complications.

Additionally, this study was conducted at a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings. Blinding of participants was not feasible due to the nature of the interventions, which could introduce performance bias. Postoperative outcomes were assessed only up to 24 hours after ambulation; long-term outcomes were not evaluated. Although the results indicate that early ambulation can reduce postoperative pain and vomiting after sleeve gastrectomy, caution should be exercised when applying these findings to different patient populations, surgical teams, or hospital settings. Further multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are recommended to confirm these findings.

Conclusion

Compared to GA and the conventional method, EA is more effective in reducing the intensity of pain and the frequency of vomiting among patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy.

Acknowledgments: This study was derived from a Master’s thesis in Nursing and Midwifery at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences. The authors are grateful to the staff of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Department of Nursing and Midwifery, the nurses of Ghadir Mother and Child Hospital affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, the participants, including patients undergoing surgery, and all those who contributed to this study.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (IR.YUMS.REC.1395.30) and registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT2016051527904N1).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Sadat SJ (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Shirazi F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Zoladl M (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (10%); Koohpeyma M (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: This study was funded by Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

Nowadays, the incidence of morbid obesity has increased worldwide and has become a global problem [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization, it is predicted that by 2030, almost 60% of the world’s population, or 3.3 billion individuals, may suffer from the effects of excessive weight gain [3]. In addition to life restrictions, obesity can lead to disorders such as cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, gastrointestinal issues, musculoskeletal problems, renal complications, neurological conditions, and various types of cancer [4, 5]. Obesity can be treated using a variety of techniques, including pharmacological methods, low-calorie diets, behavior modification, exercise, and surgery [6]. Evidence has indicated that non-surgical methods have not been effective in achieving weight reduction among individuals suffering from morbid obesity [7, 8]. Thus, there has been an increasing tendency to utilize surgical methods for weight reduction. Therefore, it is essential to select an appropriate surgical technique and take proper measures to minimize postoperative complications [9]. To date, there is a rising trend towards bariatric surgeries due to their long-term impacts on weight reduction. Studies have revealed the effectiveness of this surgical method in the treatment of obesity-related disorders [9, 10].

In recent years, bariatric surgeries have ranked second among abdominal surgeries [11]. One of the restrictive procedures in bariatric surgery is sleeve gastrectomy, in which the stomach volume is reduced to 100-150 cc by removing the greater curvature, causing the stomach to take on the shape of a tube. This method also results in a decline in the number of cells producing ghrelin (an appetite regulator), thereby reducing its serum level and helping to decrease obesity [12, 13]. Since 2014, sleeve gastrectomy has been the most common surgical operation for obesity treatment [2, 14]. Although this laparoscopic surgery is effective in weight reduction, it can be accompanied by both short- and long-term complications. The short-term complications of this surgery include pain, nausea, vomiting, and hemodynamic disorders [15, 16]. If these postoperative complications are not controlled and treated, they can increase the length of hospital stay and, consequently, the treatment costs [17].

Routine postoperative care includes bed rest until vital signs and consciousness stabilize. Nonetheless, some researchers believe that long-term bed rest in a supine position is recommended based on physicians’ opinions and experiences rather than scientific evidence [18]. On the other hand, prolonged immobility can increase the risk of numerous complications in the gastrointestinal, respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems, as well as skin issues. It can also lead to nausea, vomiting, chronic constipation, muscle pain, acute back pain, arterial thrombosis, and embolism [19]. Therefore, in some healthcare centers, patients who have undergone extensive surgical operations, including sleeve gastrectomy, are encouraged to engage in early ambulation [20]. Although early ambulation has been effective in reducing postoperative complications and the length of hospital stay [21], it has been accompanied by limitations and obstacles, including a lack of information among treatment teams and patients, as well as numerous attachments to the patient’s body [22]. Additionally, studies have shown a paucity of evidence-based information regarding this protocol, resulting in the continuation of conventional care.

Sleeve gastrectomy, despite being an effective and widely performed bariatric procedure, is often associated with postoperative complications such as pain, nausea, and vomiting. Early mobilization after surgery has been shown to improve recovery and reduce such complications in other types of surgery; however, evidence regarding the optimal timing and approach to ambulation after sleeve gastrectomy remains limited. Considering the growing number of surgical interventions for obesity treatment, there is an increasing need for low-risk strategies that can accelerate postoperative recovery and minimize complications such as pain and vomiting. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effects of early and gradual ambulation on postoperative complications after sleeve gastrectomy.

Instrument and Methods

Study design and participants

This single-center, parallel-group randomized clinical trial was conducted on morbidly obese patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy at the bariatric surgery ward of Ghadir Mother and Child Hospital in Shiraz, Iran from June to September 2016. According to the inclusion criteria, which included having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher and being within the age range of 18-55 years, and the exclusion criteria, which consisted of a history of mental disorders, respiratory disorders, morphine addiction, cigarette smoking, musculoskeletal disorders due to body positions during the operation, abnormal problems, such as vascular damage, removal of an excessive portion of the stomach, anastomotic leak, and inability to tolerate the study protocol, 132 eligible sleeve gastrectomy candidates were selected and allocated to the gradual ambulation (GA) group, early ambulation (EA) group, and control group using block randomization.

Based on the results of Asadi et al.’s study [23], considering α=0.01 and a power of 80%, along with a 15% loss rate, the sample size was estimated to be 44 eligible patients in each study group. Therefore, a total of 132 patients were enrolled in the research.

Participants were consecutively recruited from patients scheduled for elective sleeve gastrectomy. Random allocation was performed in a 1:1:1 ratio using a computer-generated randomization list with a block size of six. Allocation concealment was ensured by using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes prepared by a researcher not involved in enrollment or data collection. All participants provided written informed consent before surgery. Follow-up assessments were conducted during hospitalization and one week after surgery to evaluate postoperative complications and recovery outcomes.

Instrument

Data were collected using a demographic information form, a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), and a form for gathering information about the surgery and postoperative complications, including the length of operation and frequency of vomiting, among others. The demographic information form included the patients’ age, sex, education level, occupation, and marital status. The patients’ weight and height were also measured prior to the operation. After the operation, when the patients were discharged from the recovery room and admitted to the ward, another form was used to record information about the length of surgery, duration of stay in the recovery room, and frequency of vomiting.

Pain intensity was assessed using a VAS, which is a 10 cm ruler with the left end representing no pain and the right end representing the most severe pain. The patients were asked to mark their pain intensity on the ruler at different time points. Then, one of the researchers measured the patients’ pain intensity in centimeters and recorded it as the pain score, which could range from zero to ten [24]. The validity and reliability of the visual analogue scale have been demonstrated in numerous studies [25, 26].

The frequency of vomiting was recorded by the attending nurse during the same time intervals. Secondary observations included the presence of nausea, time to first mobilization, and length of hospital stay. All assessments were performed by a trained nurse who was blinded to group allocation.

Intervention

All ethical considerations were observed, and all necessary permissions for conducting the research were obtained from the relevant administrators. Written informed consent forms were also obtained from all participants.

Prior to the intervention, the participants were provided with the necessary explanations and asked to complete the demographic information form. In the GA group, gradual ambulation was carried out through the following process: the patients were placed in a supine position after entering the ward. During the first two hours, the head of the bed was raised by 15 degrees. During the third and fourth hours, the head of the bed was raised by 30 and 45 degrees, respectively. The head of the bed was then returned to 15 degrees during the fifth and sixth hours. Additionally, the patients were encouraged to move their bodies to the left and right. After that, they were asked to change the positions of their upper and lower extremities. In the seventh hour, the patients were placed in a sitting position for five minutes. They were then allowed to sit on the chairs next to their beds for 10-15 minutes. If the patients experienced no problems, they could walk with the help of their companions in the corridor. Following that, they were allowed to walk within the ward.

In the EA group, four hours after the patients’ entrance into the ward, their level of consciousness was assessed by a nurse. If the patients were fully conscious, they sat on the bed in the presence of the nurse for ten minutes. If there was no change in the patients’ level of consciousness, they were allowed to sit on the chairs next to their beds for five minutes. At this stage, the patients’ levels of consciousness and mental status were evaluated again. If the patients were in appropriate condition, they could walk 15 meters around their beds with the assistance of their companions. After two hours, the patients were asked to sit on the bed for five minutes and then on the chair for five minutes. If no problems occurred, they could walk in the corridor with the help of their companions for five minutes. During this stage, a nurse accompanied the patients to prevent falls. This process was repeated every four hours from 6 AM until 12 AM.

In the control group, the patients received routine care services. Depending on their mental status and willingness, and irrespective of time, they were encouraged to walk at least once on the first day and three times on the second day.

All interventions were supervised by a trained nurse who ensured patient safety, prevented falls, and documented adherence to the ambulation protocols. All patients across the three groups received identical postoperative analgesic and antiemetic regimens to control for medication-related effects. Environmental and surgical conditions were kept constant for all participants to minimize confounding factors.

The three groups were compared in terms of postoperative complications, including pain and frequency of vomiting, at five time points: upon entering the ward and immediately after, as well as at 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours after ambulation.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 21 software by a statistician who was blind to the study groups. Statistical comparisons were conducted using appropriate tests, such as chi-square, ANOVA, and repeated measures ANOVA.

Findings

Among the 132 eligible sleeve gastrectomy candidates, 94 were female (71.2%) and 38 were male (28.8%). The majority of the study participants were married (75%), homemakers (39.4%), and held a degree higher than a diploma (60.6%). The mean age of the participants was 32.1±7.1 years, and their mean BMI was 44.4±8.6kg/m². The mean age of the participants was 31.1±7.4 years in the GA group, 31.2±6.1 years in the EA group, and 34.0±7.5 years in the control group (p-value=0.09). The mean BMI was 43.5±3.0kg/m²in the GA group, 45.6±4.3kg/m²in the EA group, and 45.3±5.9kg/m²in the control group (p-value=0.06). The mean duration of surgery was 150.3±38.9 minutes in the GA group, 155.8±29.3 minutes in the EA group, and 159.9±30.0 minutes in the control group (p-value=0.39). The mean duration of stay in the recovery room was 86.8±34.8 minutes in the GA group, 78.3±27.7 minutes in the EA group, and 92.7±36.2 minutes in the control group (p-value=0.1).The three groups were similar in terms of age, sex, marital status, education level, occupation, length of surgery, and length of stay in the recovery room (p>0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic data of the participants (n=44 per group)

There was no significant difference among the three groups regarding the mean pain intensity at baseline (p=0.73). However, there was a significant reduction in pain intensity in the three groups over time (p<0.001; Figure 1). Moreover, between-group comparisons indicated no significant difference among the three groups concerning pain intensity at baseline and immediately after ambulation. However, significant differences were observed in this regard at 6, 12, and 24 hours after ambulation. The Bonferroni post-hoc test showed that the mean intensity of pain was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the GA (p<0.001) and control (p<0.001) groups. Nonetheless, the GA group did not show a significant difference from the control group in this respect. Furthermore, significant differences were detected between both intervention groups and the control group concerning the mean intensity of pain 24 hours after ambulation (p=0.036 for the GA group and p<0.001 for the EA group). Additionally, the mean intensity of pain was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the GA group (p<0.001).

Figure 1. Mean changes in the severity of patients’ pain in terms of measurement time.

There was no significant difference among the three groups regarding the frequency of vomiting at baseline and immediately after ambulation. However, a significant difference was observed among the three groups in this regard at 6, 12, and 24 hours after ambulation (p<0.05; Figure 2). The frequency of vomiting was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the GA (p<0.001) and control (p<0.001) groups six hours after ambulation. However, the GA group did not show a significant difference from the control group in this respect. After 12 hours, the frequency of vomiting was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the GA (p=0.001) and control (p<0.001) groups. Nonetheless, no significant difference was found between the GA and control groups in this regard. After 24 hours, the frequency of vomiting was significantly lower in the EA group than in the GA group (p=0.01), but there was no significant difference from the control group (p=0.1; Table 2).

Figure 2. Mean changes in patients' vomiting frequency in terms of measurement time.

Table 2. Comparisons of mean changes in complications at five measurement points

Discussion

This research aimed to determine the effect of early and gradual ambulation on postoperative complications after sleeve gastrectomy. Compared to GA and the conventional method, EA was effective in reducing the intensity of pain and the frequency of vomiting at 6, 12, and 24 hours after the operation. Similarly, Lee et al. conducted a study on 100 patients undergoing colon surgery in South Korea in 2011 and found that, compared to conventional care, early ambulation in the form of a rehabilitation program can decrease complications, as well as the time required for patients to return to their daily activities [27].

There was a decline in the mean intensity of pain in all three groups. Between-group comparisons indicated a more pronounced decrease in the early ambulation group compared to both the control group and the gradual ambulation group after six hours. Although a significant difference was observed between the gradual ambulation group and the control group at some time points, the decrease was most prominent in the early ambulation group. Similarly, Drolet et al. conducted a study in California in 2013 and concluded that ambulation results in a decrease in pain as well as the need for sedative drugs, leading to earlier discharge of patients from the ICU [28]. Alaa Eldin et al. showed that GA reduces pain among patients undergoing angiography [29]. In contrast, Vosouqian et al. stated that EA has no effect on the reduction of headache among patients undergoing cesarean sections [30]. After laparoscopic surgeries, pain usually results from phrenic nerve stimulation, the entry of laparoscopic gas into the peritoneum, and surgical incisions [31], which plays a critical role in increasing the length of hospital stay and treatment costs. In this context, some studies have indicated that rehabilitation and movement are more effective in reducing postoperative pain intensity compared to the size of surgical incisions [32, 33]. Walking after the operation may enhance the absorption of laparoscopic gases, thereby decreasing the intensity of abdominal pain [34].

Another complication investigated was the frequency of vomiting. This phenomenon is prevalent after bariatric surgeries due to the use of anesthesia medications, manipulation of the gastrointestinal system, and the utilization of laparoscopic gases. Major et al. conducted a study in 2018 and revealed that the prevalence of vomiting is higher in sleeve gastrectomy than in other bariatric surgeries [35]. Studies have also shown that two-thirds of the patients undergoing bariatric surgeries experience postoperative nausea and vomiting [36]. EA could significantly reduce the frequency of vomiting compared to gradual ambulation and routine care. In the same vein, Deng et al. showed that implementing an abdominal-based early progressive mobilization program in critically ill, intubated patients significantly improves gastric motility and reduces complications of feeding intolerance, including vomiting, abdominal distention, and diarrhea [37]. Fathi et al. also reported that placing chemotherapy patients in a half-seated position reduces the frequency of vomiting [38]. On the contrary, the review study conducted by Seok et al. indicated that movement after surgical operations leads to the incidence of nausea and vomiting [39]. Yet, scientific evidence has shown that ambulation and increased activity can enhance peristalsis, which might reduce nausea and vomiting.

Overall, EA decreased postoperative complications among patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. Considering the increasing population of obese individuals and the resultant rise in the need for bariatric surgeries, preventing the complications of these operations is of utmost importance. The prevention of vomiting and pain is also crucial from the patients’ perspectives, as these complications can delay their discharge and increase their treatment costs. A strong point of the present study was the relative similarity of the patients and the uniform care conditions for all patients in a single ward. However, one of the uncontrollable limitations of the study was the presence of individual differences in surgical operations and anesthesia procedures. Another limitation was related to laparoscopic surgery; in fact, different laparoscopic gas pressures are used for various individuals, which can influence the incidence of postoperative complications.

Additionally, this study was conducted at a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings. Blinding of participants was not feasible due to the nature of the interventions, which could introduce performance bias. Postoperative outcomes were assessed only up to 24 hours after ambulation; long-term outcomes were not evaluated. Although the results indicate that early ambulation can reduce postoperative pain and vomiting after sleeve gastrectomy, caution should be exercised when applying these findings to different patient populations, surgical teams, or hospital settings. Further multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are recommended to confirm these findings.

Conclusion

Compared to GA and the conventional method, EA is more effective in reducing the intensity of pain and the frequency of vomiting among patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy.

Acknowledgments: This study was derived from a Master’s thesis in Nursing and Midwifery at Yasuj University of Medical Sciences. The authors are grateful to the staff of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Department of Nursing and Midwifery, the nurses of Ghadir Mother and Child Hospital affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, the participants, including patients undergoing surgery, and all those who contributed to this study.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (IR.YUMS.REC.1395.30) and registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT2016051527904N1).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Sadat SJ (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Shirazi F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Zoladl M (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (10%); Koohpeyma M (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: This study was funded by Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

Keywords:

Ambulation [MeSH], Postoperative Complications [MeSH], Gastrectomy [MeSH], Pain [MeSH], Vomiting [MeSH]

References

1. Cohen PR. Adult acquired buried penis: A hidden problem in obese men. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13067. [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.13067]

2. Biörserud C. Excess skin after bariatric surgery-patients' perspective and objective measurements [dissertation]. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg; 2015. [Link]

3. Gulinac M, Miteva DG, Peshevska-Sekulovska M, Novakov IP, Antovic S, Peruhova M, et al. Long-term effectiveness, outcomes and complications of bariatric surgery. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(19):4504-12. [Link] [DOI:10.12998/wjcc.v11.i19.4504]

4. Sierżantowicz R, Ładny JR, Lewko J. Quality of life after bariatric surgery-a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):9078. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19159078]

5. WHO. News-room fact-sheets detail obesity and overweight [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2024 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. [Link]

6. Baker JS, Supriya R, Dutheil F, Gao Y. Obesity: Treatments, conceptualizations, and future directions for a growing problem. Biology. 2022;11(2):160. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/biology11020160]

7. Cheng J, Gao J, Shuai X, Wang G, Tao K. The comprehensive summary of surgical versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oncotarget. 2016;7(26):39216-30. [Link] [DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.9581]

8. Stenberg E, Dos Reis Falcao LF, O'Kane M, Liem R, Pournaras DJ, Salminen P, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in bariatric surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations: A 2021 update. World J Surg. 2022;46(4):729-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00268-021-06394-9]

9. Ma C, Avenell A, Bolland M, Hudson J, Stewart F, Robertson C, et al. Effects of weight loss interventions for adults who are obese on mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j4849. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.j4849]

10. Alqunai MS, Alrashid FF. Bariatric surgery for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus-current trends and challenges: A review article. Am J Transl Res. 2022;14(2):1160-71. [Link]

11. Zambrano AK, Paz-Cruz E, Ruiz-Pozo VA, Cadena-Ullauri S, Tamayo-Trujillo R, Guevara-Ramírez P, et al. Microbiota dynamics preceding bariatric surgery as obesity treatment: A comprehensive review. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1393182. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fnut.2024.1393182]

12. McCarty TR, Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Effect of sleeve gastrectomy on ghrelin, GLP-1, PYY, and GIP gut hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2020;272(1):72-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003614]

13. Sharma G, Nain PS, Sethi P, Ahuja A, Sharma S. Plasma ghrelin levels after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in obese individuals. Indian J Med Res. 2019;149(4):544-7. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_984_18]

14. Chen G, Zhang GX, Peng BQ, Cheng Z, Du X. Roux-En-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy plus procedures for treatment of morbid obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2021;31(7):3303-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11695-021-05456-0]

15. Koohpyma M, Sadat S, Afrasiabifar A, Zoladl M. Effect of early mobilization on hemodynamic parameters of patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy; A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Care Skills. 2020;1(2):55-61. [Link] [DOI:10.52547/jccs.1.2.55]

16. Koohpeyma M, Sadat S, Zoladl M, Afrasiabifar A. Effect of gradual mobilization with bed activity on hemodynamic parameters in patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. J Clin Care Skills. 2020;1(3):139-46. [Link] [DOI:10.52547/jccs.1.3.139]

17. Arterburn DE, Telem DA, Kushner RF, Courcoulas AP. Benefits and risks of bariatric surgery in adults: A review. JAMA. 2020;324(9):879-87. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.12567]

18. Carvalho L, Almeida RF, Nora M, Guimarães M. Thromboembolic complications after bariatric surgery: Is the high risk real?. Cureus. 2023;15(1):e33444. [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.33444]

19. Parola V, Neves H, Duque FM, Bernardes RA, Cardoso R, Mendes CA, et al. Rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility: A scoping review protocol. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):12033. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182212033]

20. Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Garvey WT, Hurley DL, McMahon MM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient-2013 update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Endocr Pract. 2013;9(2):337-72. [Link] [DOI:10.4158/EP12437.GL]

21. Gustafsson U, Scott M, Schwenk W, Demartines N, Roulin D, Francis N, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. World J Surg. 2013;37(2):259-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00268-012-1772-0]

22. Liebermann M, Awad M, Dejong M, Rivard C, Sinacore J, Brubaker L. Ambulation of hospitalized gynecologic surgical patients: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(3):533-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318280d50a]

23. Asadi F, Ebrahim H, Mazloum R, Jangjo A, Sabouri Noghabi M. The effect of early ambulation on nausea in patients undergoing Appendectomy. Evid Based Care J. 2013;3(1):49-58. [Persian] [Link]

24. Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Ostelo RW, Boers M, Tugwell P, Terwee CB. Measurement properties of visual analogue scale, numeric rating scale, and pain severity subscale of the brief pain inventory in patients with low back pain: A systematic review. J Pain. 2019;20(3):245-63. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.07.009]

25. Javanbakht M, Keshtkaran A, Shabaninejad H, Karami H, Zakerinia M, Delavari S. Comparison of blood transfusion plus chelation therapy and bone marrow transplantation in patients with β-thalassemia: Application of SF-36, EQ-5D, and visual analogue scale measures. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(11):733-40. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.113]

26. Gholami E, Mohammad Hossini S, Moradian F, Manzouri L, Karimi Z. Effect of pilates on pain control and wound healing in second degree burn patients; A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Care Skills. 2023;4(2):71-5. [Link]

27. Lee TG, Kang SB, Kim DW, Hong S, Heo SC, Park KJ. Comparison of early mobilization and diet rehabilitation program with conventional care after laparoscopic colon surgery: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(1):21-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fcdb3e]

28. Drolet A, DeJuilio P, Harkless S, Henricks S, Kamin E, Leddy EA, et al. Move to improve: The feasibility of using an early mobility protocol to increase ambulation in the intensive and intermediate care settings. Phys Ther. 2013;93(2):197-207. [Link] [DOI:10.2522/ptj.20110400]

29. Alaa Eldin SMA, Elrefaey NMM, Khamis EAR, Abdelhamed HM. The effect of different positions on clinical outcomes of post coronary catheterization patients: Comparative trial. Egypt J Health Care. 2021;12(3):1899-914. [Link] [DOI:10.21608/ejhc.2021.269397]

30. Vosouqian M, Sadri A, Ghsemi M, Dahi M, Dabagh A. The effect of early ambulation on the prevalence of postoperative headache in patients undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia. Res Med. 2012; 36 (2):89-92. [Persian] [Link]

31. Sao CH, Chan-Tiopianco M, Chung KC, Chen YJ, Horng HC, Lee WL, et al. Pain after laparoscopic surgery: Focus on shoulder-tip pain after gynecological laparoscopic surgery. J Chin Med Assoc. 2019;82(11):819-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000190]

32. Berend KR, Lombardi A, Mallory TH. Rapid recovery protocol for peri-operative care of total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients. Surg Technol Int. 2004;13:239-47. [Link]

33. Joshi GP, Kehlet H. Postoperative pain management in the era of ERAS: An overview. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2019;33(3):259-67. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bpa.2019.07.016]

34. Hinkle JL, Cheever KH. Brunner and Suddarth's textbook of medical-surgical nursing. Maharashtra: Wolters Kluwer India Pvt Ltd; 2018. [Link]

35. Major P, Stefura T, Małczak P, Wysocki M, Witowski J, Kulawik J, et al. Postoperative care and functional recovery after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs. laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass among patients under ERAS protocol. Obes Surg. 2018;28(4):1031-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11695-017-2964-3]

36. Halliday TA, Sundqvist J, Hultin M, Walldén J. Post‐operative nausea and vomiting in bariatric surgery patients: An observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017;61(5):471-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/aas.12884]

37. Deng LX, Lan-Cao, Zhang LN, Dun-Tian, Yang-Sun, Qing-Yang, et al. The effects of abdominal-based early progressive mobilisation on gastric motility in endotracheally intubated intensive care patients: A randomised controlled trial. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2022;71:103232. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2022.103232]

38. Fathi M, Nasrabadi AN, Valiee S. The effects of body position on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(6):e17778. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.17778]

39. Seok Y, Suh EE, Yu SY, Park J, Park H, Lee E. Effectiveness of integrated education to reduce postoperative nausea, vomiting, and dizziness after abdominal surgery under general anesthesia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):6124. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18116124]