Volume 6, Issue 4 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(4): 225-232 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.YUMS.REC.1403.076

History

Received: 2025/08/7 | Accepted: 2025/09/18 | Published: 2025/09/28

Received: 2025/08/7 | Accepted: 2025/09/18 | Published: 2025/09/28

How to cite this article

Mohsenian S, Yazdanpanah I, Hashemimohammadabad N, Sadat Z, Hashemimohammadabad Z. Effect of Forehead Temperature Reduction on Visual Attention Accuracy and Cognitive Status in Patients with Schizophrenia. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (4) :225-232

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-454-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-454-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

S. Mohsenian1

, I. Yazdanpanah2

, I. Yazdanpanah2

, N. Hashemimohammadabad3

, N. Hashemimohammadabad3

, Z. Sadat3

, Z. Sadat3

, Z. Hashemimohammadabad *2

, Z. Hashemimohammadabad *2

, I. Yazdanpanah2

, I. Yazdanpanah2

, N. Hashemimohammadabad3

, N. Hashemimohammadabad3

, Z. Sadat3

, Z. Sadat3

, Z. Hashemimohammadabad *2

, Z. Hashemimohammadabad *2

1- Department of Ergonomic and Occupational Therapy, Rajaee Hospital, Yasuj, Iran

2- College of Medicine, Zhejiang University of Medical Sciences, Zhejiang, China

3- Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- College of Medicine, Zhejiang University of Medical Sciences, Zhejiang, China

3- Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (7 Views)

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a psychiatric disorder that affects about 1% of the general population and is a severe, chronic disease with no specific treatment [1]. The peak onset of schizophrenia usually occurs between 18 and 32 years of age, often accompanied by early behavioral problems, such as withdrawal and emotional changes [2].

Cognitive deficits during cognitive tasks are common in patients with schizophrenia [3], which impair visual attention [4]. Functional brain networks, including the frontal and parietal cortices, are known to be key elements of visual attention [5]. The main control center for visual attention in the brain is the prefrontal cortex [6]. This area of the brain is responsible for planning cognitive behaviors, such as executive functions, and for controlling cognitive processes, attention, memory, learning, and decision-making [7, 8]. The prefrontal cortex has connections with the parietal cortex, forming the fronto-parietal neural network. Visual attention requires the coordination of activity between brain regions [9]. The prefrontal cortex is a key part of the fronto-limbic network, and neuroimaging studies have shown that increased activity or connectivity in this region is observed during attentional tasks related to visual attention and working memory in patients with schizophrenia. This increase could serve as an indicator of improved attentional control, as the fronto-limbic network is responsible for attentional and executive processing [10]. Various studies have also demonstrated that neurophysiological brain activity, or brain waves, is altered during visual attention tasks in patients with schizophrenia [11-13].

The flicker fusion test is a simple, noninvasive tool that measures the flicker frequency threshold at which light appears continuous. This test can indicate visual sensitivity and attentional processing [14]. The flicker fusion frequency is the average frequency at which a person can perceive flickering light.

Decreased cognitive performance is associated with decreased flicker fusion frequency, whereas increased flicker fusion frequency is associated with improved brain function [15]. Decreased brain tissue temperature can lead to reduced blood flow to different brain regions. Lowering brain temperature has long been used as a method to decrease brain blood flow and metabolism [16-22]. It is worth noting that the average brain temperature is 37.7 degrees Celsius, which is about 1.1°C higher than the average body temperature [17].

Mild cerebral hypothermia is defined as a mean reduction of 1.84°C (0.9–2.4°C) in the cerebral cortex during one hour of cooling the skull with fluid-cooled methods, or a 2–4°C reduction during one hour of cooling the skull with a head and neck temperature-reducing device [16, 24]. Prefrontal cortex cooling is a safe and effective method for improving certain cognitive skills, such as visual attention [14]. No life-threatening complications or symptoms have been reported in relevant studies following mild cerebral hypothermia, and the safety of this method has been demonstrated in numerous studies with monitoring of vital signs [16, 23, 24–27].

Few studies have been conducted on the effects of reducing brain temperature on visual attentional accuracy; therefore, conducting research in this area is important. Most previous studies on reducing brain temperature to increase alertness and attention have been conducted in hospital intensive care units, particularly for patients with traumatic brain injury and stroke. Given the importance of optimizing the performance of individuals with schizophrenia in family, work, and social environments to provide comfort and enhance performance, as well as to create environmental conditions that align with the cognitive abilities of schizophrenic patients, this study aimed to determine the effect of reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex on the accuracy of visual attention and the cognitive status of the participants.

Materials and Methods

Design and sample

The present randomized controlled trial was conducted on patients with schizophrenia who had positive symptoms and were hospitalized in the psychiatric ward of Shahid Rajaee Hospital in Yasuj, affiliated with Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Iran, in 2024. These patients met the inclusion criteria for the study.

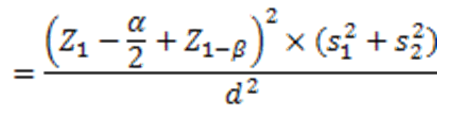

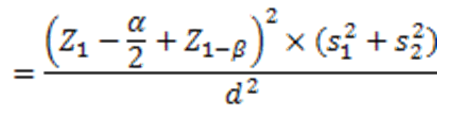

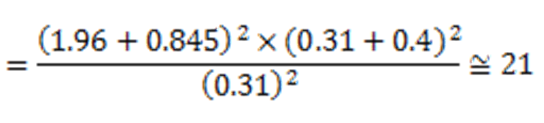

The sample size was determined based on the specific calculation formula for two-group clinical trial studies:

Where z is the standard normal value in the mentioned percentiles, α and β are the type I and II errors, respectively, and s12 and s12 are the estimates of the variances of the visual focus rate, and d is the difference in the mean visual attention rate in the two intervention and control groups. If the errors of α and β are 5% and 20%, respectively, and for s12, s22, and d are 0.31, 0.4, and 0.31, respectively, the sample size for each group is 21 patients, resulting in a total sample size of 42 patients for both groups:

The samples were selected using the convenience sampling method and assigned to two groups—intervention and control—using the block random sampling method. Participating patients entered the study after giving informed consent and meeting the inclusion criteria, which included a diagnosis of schizophrenia by a psychiatrist, having breakfast or consuming 250cc of water, adequate sleep of at least 6 hours the night before the intervention session, and taking the medication aripiprazole from the day of admission to the ward until the day of the intervention. Exclusion criteria included the presence of heart problems, use of blood pressure-regulating drugs, acute and chronic sinusitis, migraine headaches, anxiety, use of drugs, alcohol, nicotine, or coffee at least 24 hours before the study, receiving ECT, and not meeting the inclusion criteria.

Before conducting the study phases, while explaining the procedures and objectives of the study verbally to the eligible patients and their companions, the patient and the patient's companion were asked to complete and sign a consent form if they wished to participate in the study. Eligible patients were provided with information regarding the non-invasiveness of the study procedures and the confidentiality of their information. The Declaration of Helsinki was taken into account.

The data collection tools included the Rapid Visual Processing Test from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and the Flicker Fusion Test. The research intervention involved reducing the temperature of the frontal region. To eliminate the effect of the circadian cycle on cognitive activity in the brain, the study phases were conducted between 9 and 11 a.m.

This study was carried out in two phases: the first, or pre-intervention, phase included an initial assessment of visual attention accuracy and cognitive impairment immediately after performing the Rapid Visual Processing Test, while the second phase involved an intervention to reduce the temperature of the prefrontal cortex in the intervention group and a sham intervention in the control group. Before the intervention, participants were advised to eat breakfast or drink 250 cc of water, get adequate sleep of at least 6 hours, and take aripiprazole from the day of admission to the ward until the day of the intervention.

The rapid visual processing test was administered to assess visual attention accuracy in both the intervention and control (sham) groups. The subject sits facing the monitor during the test. The time required to complete the main test is 10 minutes. Subjects are shown a sequence of three numbers, which is displayed randomly on the monitor in front of the subject each time. The numbers are shown at a rate of 100 numbers per minute. The person must touch a specific location in the middle of the monitor upon seeing a predetermined sequence of numbers. The number of errors is recorded by the software, and the number of correct responses is determined in the rapid visual processing test.

Additionally, the Flicker Fusion Test was administered to both the intervention and control groups immediately after the completion of the rapid visual processing test to determine the flicker fusion frequency, which is an important diagnostic indicator for assessing the severity of cognitive impairment [28, 29]. The validity and reliability of the Flicker Fusion Test have been established [15, 30-34].

The Flicker Fusion Test was also performed with 10 repetitions to determine the flicker fusion frequency (using an electronic flicker fusion device, model RT-881, from Sina Iran Company) [35]. To conduct the Flicker Fusion Test, the subjects place their foreheads on the monitor of the light source device. Light with a frequency of 30 Hz is flashed into the subject’s eyes in a flickering manner. For each subject, 10 ascending and descending measurements are performed. In the ascending measurement, the light frequency increases from 30Hz until the subject perceives the moving light as fixed. The frequency at which the subject sees the flickering light as constant is recorded. In the descending test, the frequency of the constant light is reduced from 50Hz until the subject perceives the constant light as flickering. The frequency at which the subject sees the constant light as flickering is also recorded. The average of each ascending and descending test is calculated. The average of the 10 ascending and descending tests is referred to as the flicker fusion frequency, which is an important diagnostic criterion for determining the severity of cognitive impairment.

Phase 2: This phase involved reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex and evaluating physiological parameters. The modified WELkins EMT cooling device cover and skin temperature sensor were placed on the frontal skin area of both the intervention and control groups. For the intervention group, a cooling liquid with a constant temperature of 4°C flowed through the cooling device cover for 1 hour [23]. The cooling device was also applied to the forehead area of the control group, but the temperature of the liquid inside was 25°C (room temperature; sham). Physiological parameters, including blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, and sublingual temperature, were monitored and recorded at 0, 30, 45, and 60 minutes to ensure the safety of the intervention group and to examine changes in these parameters in both groups. Blood pressure and heart rate were measured using a portable wrist blood pressure monitor, Beurer BM47, while blood oxygen saturation was measured using a Beurer PO80 finger pulse oximeter at the end of this phase. A medical thermometer was used to assess sublingual temperature. The room temperature was maintained at a constant 25°C. If a participant reported a headache or discomfort, the temperature reduction process was stopped immediately, and the participant was referred to the team physician. This phase was supervised by a general practitioner.

Immediately after the one-hour prefrontal temperature reduction process, the cooling device cover was removed. Subjects in both groups then participated in the Rapid Visual Processing Test again. Following this test, the Flicker Fusion Test was administered to subjects in both groups to compare the severity of cognitive impairment in this phase with that of the first phase. To prevent bias and to account for the circadian rhythm of the subjects, the assessments for this phase and the first phase were conducted in one session and at the same time.

The double-blinding was done so that the principal investigator and the subjects in both groups were blinded to the type of intervention, and only the department head was aware of the type of intervention in each group.

The primary outcome was the patients’ visual attention accuracy and cognitive status, while the secondary outcomes included determining the correlation between visual attention accuracy and cognitive status, as well as assessing physiological parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen saturation percentage, and sublingual temperature of the patients.

SPSS 25 software was used to analyze the data. The normality of the quantitative data was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In the second phase, repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess changes in physiological parameters, including sublingual temperature, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and blood oxygen saturation. In both the first and second phases, paired t-tests, independent t-tests, and repeated measures ANOVA were used to compare the accuracy of visual attention and flicker fusion frequency before and after the intervention. Linear regression and the Pearson correlation coefficient were then calculated to examine the relationship between flicker fusion frequency and visual attention accuracy. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at less than 0.05.

Findings

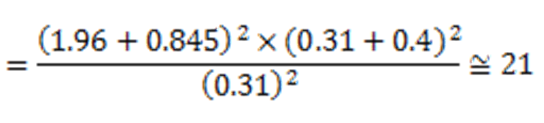

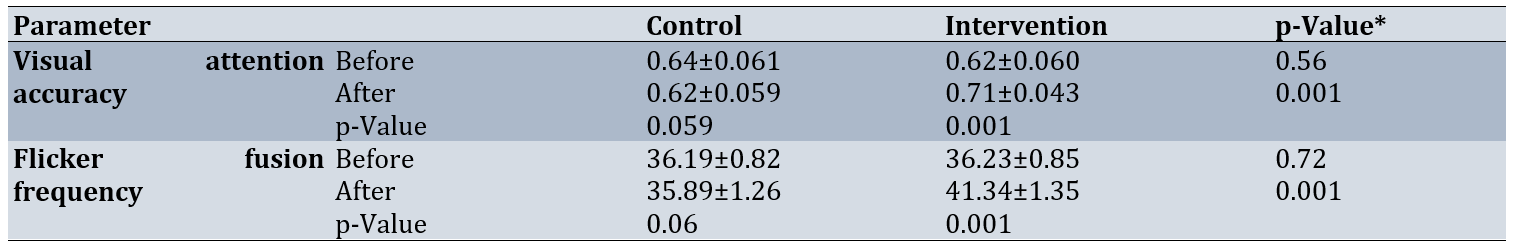

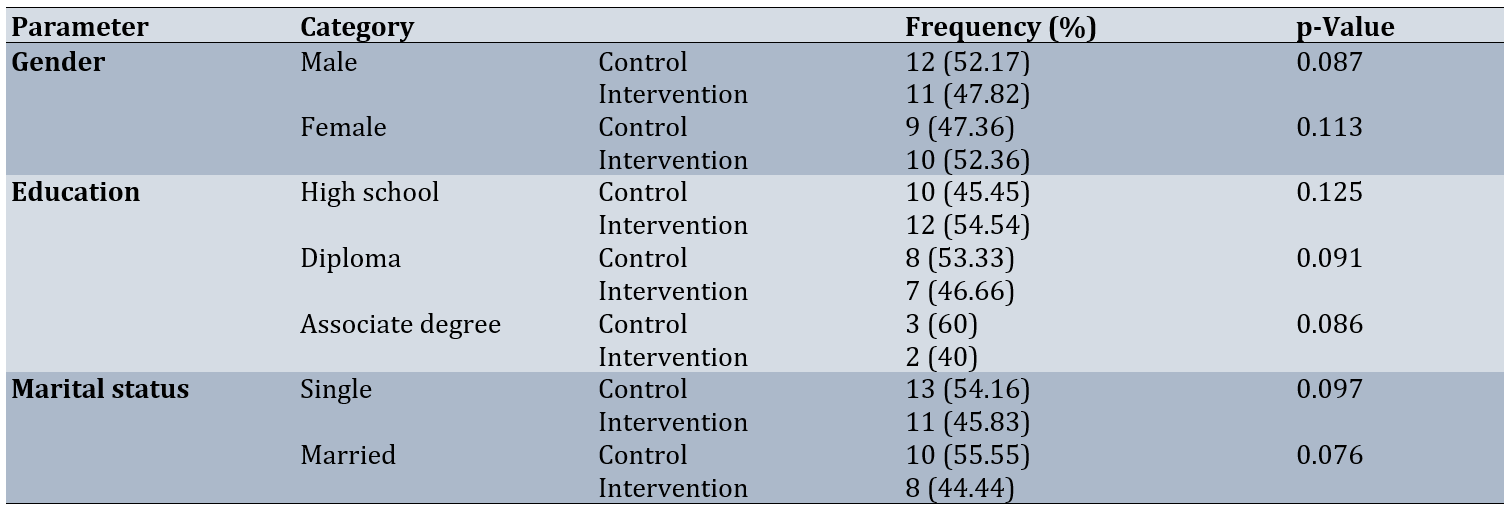

Forty-two patients were analyzed, of whom 23 were male (54.76%) and 19 were female (45.24%). The mean age of the participants was 22.16±2.18 yaers. There was no significant difference in demographic factors, including gender, educational status, and marital status, between the intervention and control groups (p<0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics of participants

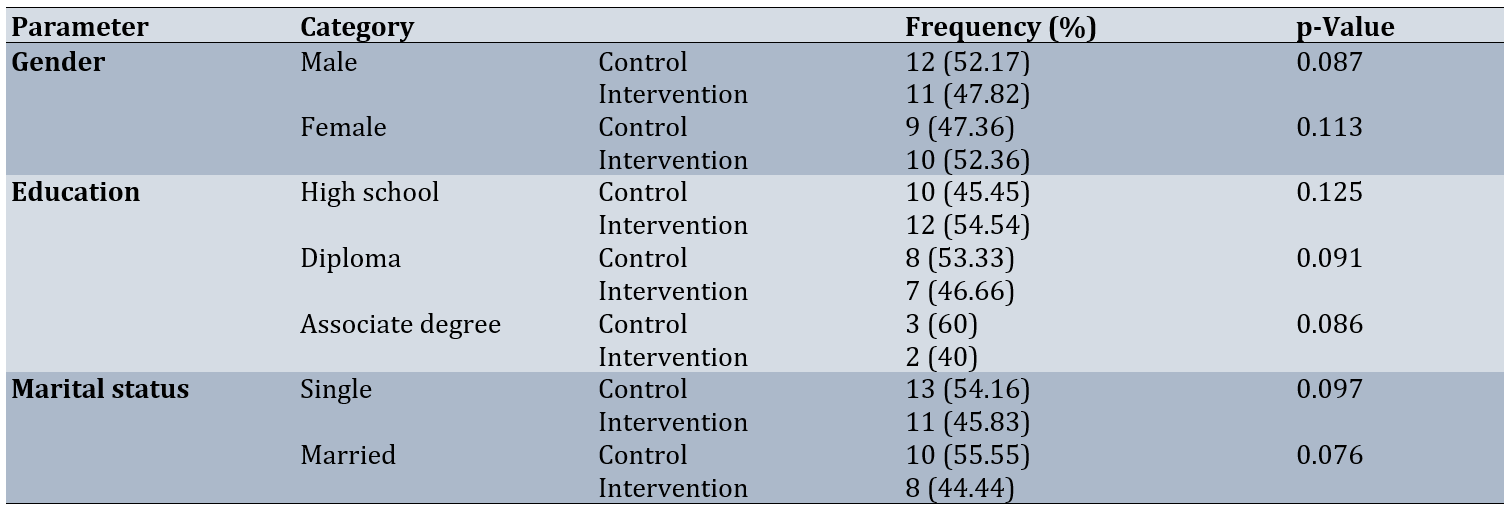

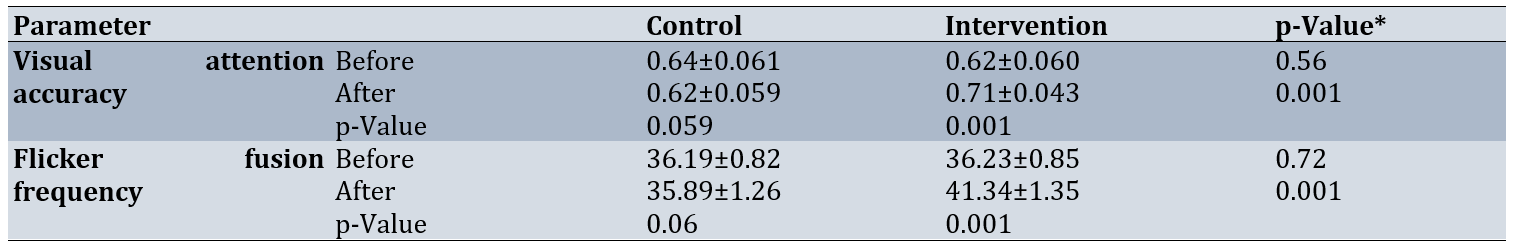

The average changes in the number of correct responses in the rapid visual processing test in the intervention group compared to the control group before the intervention were not significant (p=0.56). However, after the intervention, the average of these changes increased significantly in the intervention group compared to the control group (p=0.001). In the intra-group comparison using a paired t-test, the passage of time from the first phase to the second phase did not have a significant effect on the average change in the number of correct responses for the control group (p=0.059). In contrast, there was a significant increase in the average change in the number of correct responses after the intervention (p=0.001).

Additionally, there was no significant difference in flicker fusion frequency between the intervention and control groups before the intervention (p=0.72). However, after the intervention, there was a significant increase between the groups (p=0.001). In the intra-group comparison, there was no significant difference between the mean scores of the two time points in the control group, but in the intervention group, a significant increase was found in the mean scores before and after the intervention (p=0.001; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of mean visual attention accuracy and flicker fusion frequency between the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention

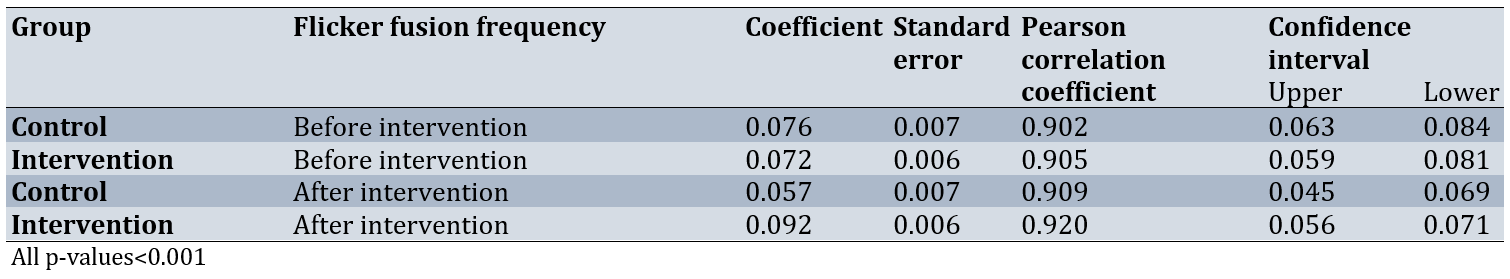

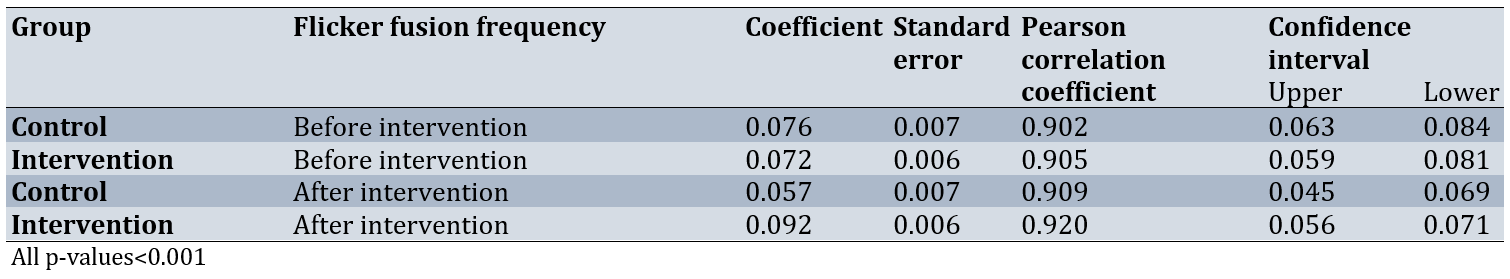

Linear regression analysis and the Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a direct relationship between flicker fusion frequency and the probability of correct responses in the Rapid Visual Processing Test in both phases and both groups (p<0.001). However, in the control group, a decrease in the probability of correct responses in the Rapid Visual Processing Test from the first to the second phase was accompanied by a significant decrease in flicker fusion frequency. Conversely, in the intervention group, the increase in the probability of correct responses in the rapid visual processing test was accompanied by a significant increase in flicker fusion frequency (p<0.001; Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation between flicker fusion frequency and visual attention accuracy in the rapid visual processing test in both groups before and after the intervention

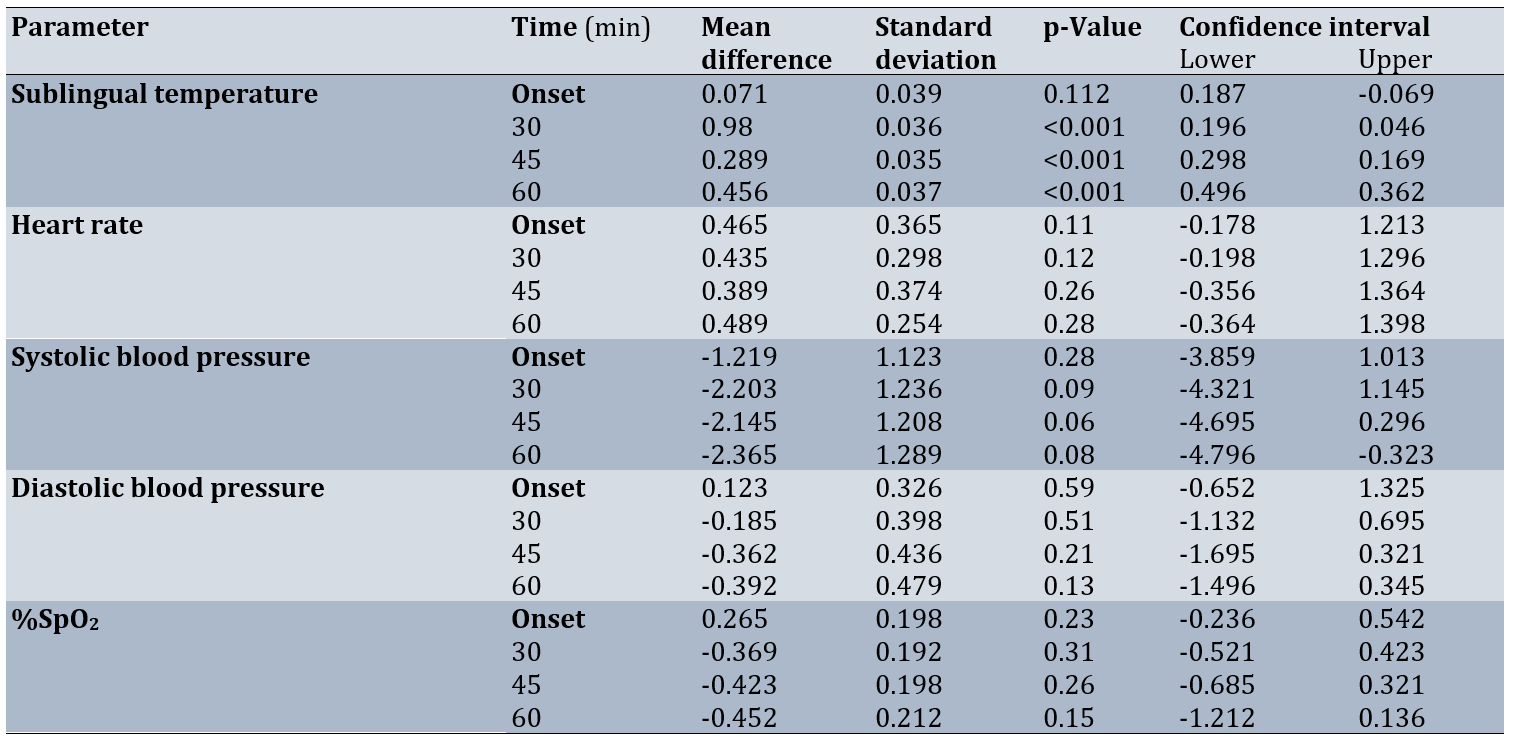

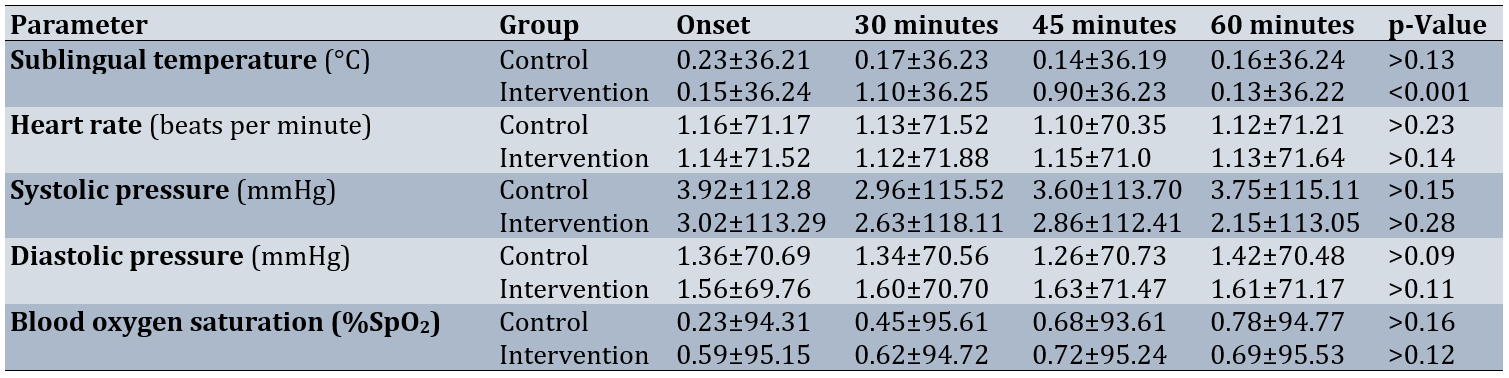

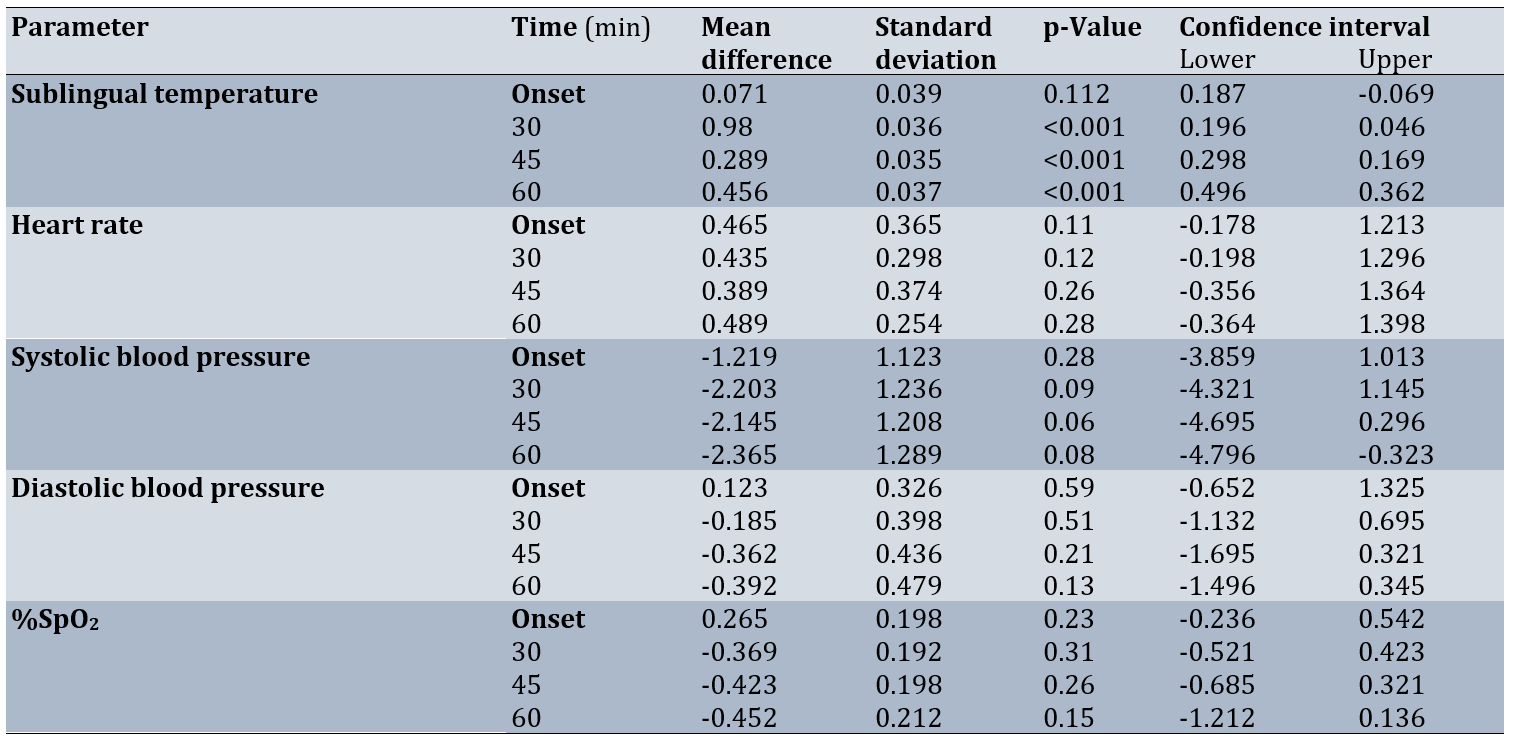

At baseline, there was no significant difference in sublingual temperature between the two groups (p=0.112), but after 45, 30 and 60 minutes, there was a significant decrease in the sublingual temperature of the intervention group (p<0.001) and there was no significant difference in this regard in the control group (p>0.001).

For sublingual temperature, the interaction effect of time and intervention was not significant (p>0.13), so that in the control group, there was no significant change in sublingual temperature from the first phase to the second phase, but the effect of the intervention in the intervention group was still significant and led to a significant decrease in the sublingual temperature of the intervention group (p<0.001; Table 4).

Table 4. Comparisons of physiological parameters between the intervention and control groups by measurement time

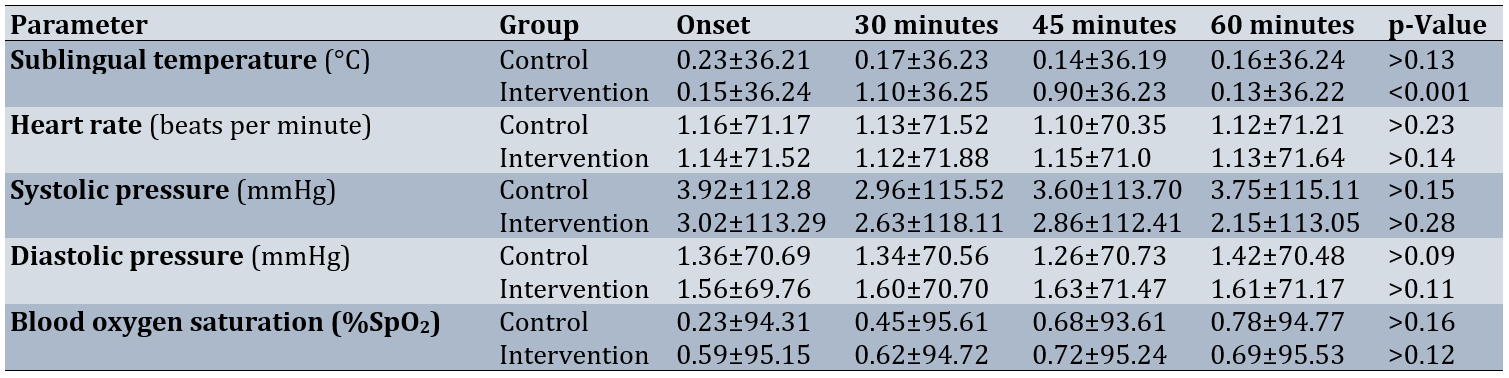

However, for other physiological parameters, including heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure, the interaction between time and intervention was not significant (p>0.001). In addition, for both groups, there were no significant changes in mean heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and blood pressure in the second phase (p>0.001; Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of mean physiological parameters in each group

Discussion

The present study aimed to determine the effect of reducing the temperature of the frontal region on visual attention accuracy and cognitive status in patients with schizophrenia. Reducing the temperature of the frontal cortex led to a significant improvement in the accuracy of visual attention in patients in the intervention group. Immediately after the actual intervention, the number of correct responses in the rapid visual processing test in the second phase increased significantly compared to the first phase in the intervention group. In contrast, the number of correct responses in the control group decreased in the second phase compared to the first phase, although this decrease was not significant. These results are consistent with those of Lee et al., Jackson et al., and Mohsenian et al. [14, 18, 23]. However, these studies were conducted on normal, non-diseased individuals. As also observed in the results of the flicker fusion test, the decrease in the accuracy of sustained visual attention in the control group from the first phase to the second phase is attributed to cognitive weakness in the prefrontal cortex and subsequent dysfunction in the fronto-arthro.

As mentioned, the changes in visual attention accuracy in the intervention group after reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex are consistent with the studies by Jackson et al. and Mohsenian et al. [14, 23]. Although the study by Jackson et al. found a significant increase in correct responses to the 1-back test (a computer test to assess working memory) after reducing brain temperature in healthy individuals, no significant changes in reaction time were observed in other cognitive tests, such as the speed test, Stroop test, and 2-back test. Therefore, more studies on reducing brain temperature in both patients and healthy individuals are needed to determine the validity of these findings.

Lee et al. conducted a brain temperature reduction intervention on healthy individuals. Our results are also consistent with those of Lee et al., in which reducing the brain temperature of healthy individuals led to a decrease in reaction time in the psychomotor attention test and a decrease in the number of errors, although there was a slight improvement in the memory test [18]. The findings of Wang et al.’s study showed that cooling the whole body for 90 minutes in 10°C water led to changes in the neurophysiological activity of the brain, resulting in an increase in correct responses in the double-digit addition task, but there was no significant change in reaction time in the psychomotor attention test [24].

A few studies have been conducted in recent years to investigate the effect of reducing brain temperature on cognitive functions, including attention and memory. Most studies have examined the effectiveness of reducing brain temperature in increasing overall brain alertness in patients with stroke and traumatic brain injury, or in reducing surgical complications in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Fischer et al. demonstrated that reducing head temperature in patients with traumatic brain injury resulted in a significant increase in the Glasgow Coma Index during hospitalization [36]. Additionally, Poli et al. showed that reducing frontal head temperature led to an increase in the level of consciousness in stroke patients [37].

Flicker fusion frequency, as a valid indicator of the severity of cognitive impairment, indicated that attentional accuracy improved after reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex. Specifically, an increase in the number of correct responses in the Rapid Visual Processing Test in the second phase compared to the first phase was associated with a significant increase in flicker fusion frequency in the intervention group. Conversely, the control group exhibited a significant decrease in flicker fusion frequency in the second phase compared to the first phase. The changes in the mean flicker fusion frequency in the present study are consistent with the results of Coull et al. and Lim et al. [38, 39]. There was a direct correlation in both groups across both phases. Therefore, this finding, along with previous studies, can enhance the validity of the Flicker Fusion test in determining the severity of cognitive weakness or fatigue.

Luczak et al. found that after visual focus during a 15-minute cognitive task, the values of flicker fusion frequency decreased from 0.5 to 6Hz, indicating cognitive impairment [28]. Additionally, in the study by Ma et al., the mean flicker fusion frequency decreased to 2.16 Hz after performing a visual search test for 10 minutes [29]. The changes in flicker fusion frequency from the second phase to the first phase are consistent with the studies of Luczak et al. and Ma et al.

The reduction in prefrontal cortex temperature led to significant changes in sublingual temperature during the intervention periods in the intervention group, which is consistent with the results of Mohsenian et al. [14]. In contrast, the study by Jackson et al. observed no significant changes in sublingual temperature [23]. This difference is likely related to both the method used for reducing brain temperature and its effects on physiological parameters, as well as the characteristics of the target group studied. In the study by Jackson et al., the reduction in brain temperature resulted in significant changes in inner ear temperature; however, due to a lack of the necessary tools, the assessment of inner ear temperature was not conducted in the present study.

There were no significant changes in heart rate and blood pressure between the two groups. Additionally, there were no significant changes in blood oxygen saturation between the two groups, indicating normal blood oxygen saturation levels during brain temperature reduction. These results are consistent with those of Mohsenian et al. and Jackson et al. [14, 23]. Kallmünzer et al. showed that the rectal and inner ear temperatures of normal subjects decreased significantly during 60 minutes of brain temperature reduction, but there were no significant changes in heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, or blood oxygen saturation, and the conditions were tolerable and suitable for the subjects, which is consistent with our study [27]. Wang et al. demonstrated that if head and neck cooling is continued for more than 120 minutes in athletes with a history of head trauma, it can increase systolic and diastolic blood pressure by more than 15mmHg [40]. Furthermore, Walter et al. and Ku et al. showed that head and neck cooling for 30 minutes does not cause significant changes in body temperature [35, 16]. Subjects in the intervention group did not report any discomfort, such as headaches or dizziness, during the 60-minute reduction in brain temperature, which is consistent with the studies by Jackson et al., Walter et al., Kallmünzer et al., and Ku et al. [35,16, 23, 27].

Among the strengths of this research are the procedures performed under controlled conditions, with the patient hospitalized in a hospital ward and under the supervision of a physician, as well as the use of advanced devices and a team of expert medical specialists to carry out the various phases of the study, including data analysis (for example, the use of a sensitive electronic flicker fusion device to assess the severity of cognitive impairment by an expert user). This study also had limitations, including the lack of a brain wave measuring device to examine the activity of the prefrontal cortex and the frontoparietal neural network during the rapid visual processing test. Additionally, the absence of an intracranial sensor to more accurately examine changes in the temperature of the cerebral cortex and the inability to assess the long-term effects of reducing brain temperature on cognitive skills were other limitations.

Reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex led to improved visual attention accuracy and cognitive function in schizophrenia patients in the intervention group. Since the prefrontal cortex plays an important role in the fronto-parietal neural network—and as mentioned, one of the functions of this network is to control visual attention—it can be concluded that reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex resulted in decreased blood flow in this area and, subsequently, changes in the neurophysiological activity of the visual attention neural network in schizophrenia patients, which favored the improvement of visual attention accuracy. The existence of a significant relationship between changes in flicker fusion frequency supports this conclusion. From the relationship between the probability of correct responses in the rapid visual processing test and flicker fusion frequency, it can be concluded that the improvement of cognitive skills in schizophrenia patients is inversely related to cognitive impairment. It can also be concluded that the reduction in blood flow in the prefrontal cortex of these patients, following a decrease in the temperature of this area, has led to a decrease in the severity of cognitive impairment in the frontoparietal neural network and, subsequently, an improvement in performance on the rapid visual processing test. No significant changes in physiological parameters were observed that would negatively impact health during the reduction of the temperature of the prefrontal cortex. Therefore, considering the results of recent studies alongside the present study, as well as the importance of choosing non-invasive methods to improve the cognitive skills of schizophrenia patients while they perform cognitive tasks, it can be concluded that reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex is an effective and safe method for enhancing certain cognitive skills, including visual attention span. Further studies on the effect of reducing brain temperature on other cognitive skills, such as problem-solving and reaction time, as well as on physical and motor skills, such as catatonia, are recommended.

Conclusion

Cooling the prefrontal cortex effectively modulates cerebral blood flow and neurophysiological activity, leading to improved attention and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Yasuj University of Medical Sciences and the Research Department of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences for their cooperation in approving and implementing this plan. We also appreciate the cooperation of Dr. Sadati, Head of the Neurotherapy and Occupational Therapy Department at Shahid Rajaee Hospital, and the patients who participated in this study. The study was registered with the International Center for the Registration of Clinical Trials of Iran (IRCT20250119064433N1).

Ethical permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences under the code IR.YUMS.REC.1403.076.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Author’s Contribution: Mohsenian S (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Yazdanpanah I (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Hashemimohammadabad N (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Sadat Z (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Hashemimohammadabad Z (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: This article was extracted from Zahra Sadat’s thesis in medicine and was supported by Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

Schizophrenia is a psychiatric disorder that affects about 1% of the general population and is a severe, chronic disease with no specific treatment [1]. The peak onset of schizophrenia usually occurs between 18 and 32 years of age, often accompanied by early behavioral problems, such as withdrawal and emotional changes [2].

Cognitive deficits during cognitive tasks are common in patients with schizophrenia [3], which impair visual attention [4]. Functional brain networks, including the frontal and parietal cortices, are known to be key elements of visual attention [5]. The main control center for visual attention in the brain is the prefrontal cortex [6]. This area of the brain is responsible for planning cognitive behaviors, such as executive functions, and for controlling cognitive processes, attention, memory, learning, and decision-making [7, 8]. The prefrontal cortex has connections with the parietal cortex, forming the fronto-parietal neural network. Visual attention requires the coordination of activity between brain regions [9]. The prefrontal cortex is a key part of the fronto-limbic network, and neuroimaging studies have shown that increased activity or connectivity in this region is observed during attentional tasks related to visual attention and working memory in patients with schizophrenia. This increase could serve as an indicator of improved attentional control, as the fronto-limbic network is responsible for attentional and executive processing [10]. Various studies have also demonstrated that neurophysiological brain activity, or brain waves, is altered during visual attention tasks in patients with schizophrenia [11-13].

The flicker fusion test is a simple, noninvasive tool that measures the flicker frequency threshold at which light appears continuous. This test can indicate visual sensitivity and attentional processing [14]. The flicker fusion frequency is the average frequency at which a person can perceive flickering light.

Decreased cognitive performance is associated with decreased flicker fusion frequency, whereas increased flicker fusion frequency is associated with improved brain function [15]. Decreased brain tissue temperature can lead to reduced blood flow to different brain regions. Lowering brain temperature has long been used as a method to decrease brain blood flow and metabolism [16-22]. It is worth noting that the average brain temperature is 37.7 degrees Celsius, which is about 1.1°C higher than the average body temperature [17].

Mild cerebral hypothermia is defined as a mean reduction of 1.84°C (0.9–2.4°C) in the cerebral cortex during one hour of cooling the skull with fluid-cooled methods, or a 2–4°C reduction during one hour of cooling the skull with a head and neck temperature-reducing device [16, 24]. Prefrontal cortex cooling is a safe and effective method for improving certain cognitive skills, such as visual attention [14]. No life-threatening complications or symptoms have been reported in relevant studies following mild cerebral hypothermia, and the safety of this method has been demonstrated in numerous studies with monitoring of vital signs [16, 23, 24–27].

Few studies have been conducted on the effects of reducing brain temperature on visual attentional accuracy; therefore, conducting research in this area is important. Most previous studies on reducing brain temperature to increase alertness and attention have been conducted in hospital intensive care units, particularly for patients with traumatic brain injury and stroke. Given the importance of optimizing the performance of individuals with schizophrenia in family, work, and social environments to provide comfort and enhance performance, as well as to create environmental conditions that align with the cognitive abilities of schizophrenic patients, this study aimed to determine the effect of reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex on the accuracy of visual attention and the cognitive status of the participants.

Materials and Methods

Design and sample

The present randomized controlled trial was conducted on patients with schizophrenia who had positive symptoms and were hospitalized in the psychiatric ward of Shahid Rajaee Hospital in Yasuj, affiliated with Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Iran, in 2024. These patients met the inclusion criteria for the study.

The sample size was determined based on the specific calculation formula for two-group clinical trial studies:

Where z is the standard normal value in the mentioned percentiles, α and β are the type I and II errors, respectively, and s12 and s12 are the estimates of the variances of the visual focus rate, and d is the difference in the mean visual attention rate in the two intervention and control groups. If the errors of α and β are 5% and 20%, respectively, and for s12, s22, and d are 0.31, 0.4, and 0.31, respectively, the sample size for each group is 21 patients, resulting in a total sample size of 42 patients for both groups:

The samples were selected using the convenience sampling method and assigned to two groups—intervention and control—using the block random sampling method. Participating patients entered the study after giving informed consent and meeting the inclusion criteria, which included a diagnosis of schizophrenia by a psychiatrist, having breakfast or consuming 250cc of water, adequate sleep of at least 6 hours the night before the intervention session, and taking the medication aripiprazole from the day of admission to the ward until the day of the intervention. Exclusion criteria included the presence of heart problems, use of blood pressure-regulating drugs, acute and chronic sinusitis, migraine headaches, anxiety, use of drugs, alcohol, nicotine, or coffee at least 24 hours before the study, receiving ECT, and not meeting the inclusion criteria.

Before conducting the study phases, while explaining the procedures and objectives of the study verbally to the eligible patients and their companions, the patient and the patient's companion were asked to complete and sign a consent form if they wished to participate in the study. Eligible patients were provided with information regarding the non-invasiveness of the study procedures and the confidentiality of their information. The Declaration of Helsinki was taken into account.

The data collection tools included the Rapid Visual Processing Test from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and the Flicker Fusion Test. The research intervention involved reducing the temperature of the frontal region. To eliminate the effect of the circadian cycle on cognitive activity in the brain, the study phases were conducted between 9 and 11 a.m.

This study was carried out in two phases: the first, or pre-intervention, phase included an initial assessment of visual attention accuracy and cognitive impairment immediately after performing the Rapid Visual Processing Test, while the second phase involved an intervention to reduce the temperature of the prefrontal cortex in the intervention group and a sham intervention in the control group. Before the intervention, participants were advised to eat breakfast or drink 250 cc of water, get adequate sleep of at least 6 hours, and take aripiprazole from the day of admission to the ward until the day of the intervention.

The rapid visual processing test was administered to assess visual attention accuracy in both the intervention and control (sham) groups. The subject sits facing the monitor during the test. The time required to complete the main test is 10 minutes. Subjects are shown a sequence of three numbers, which is displayed randomly on the monitor in front of the subject each time. The numbers are shown at a rate of 100 numbers per minute. The person must touch a specific location in the middle of the monitor upon seeing a predetermined sequence of numbers. The number of errors is recorded by the software, and the number of correct responses is determined in the rapid visual processing test.

Additionally, the Flicker Fusion Test was administered to both the intervention and control groups immediately after the completion of the rapid visual processing test to determine the flicker fusion frequency, which is an important diagnostic indicator for assessing the severity of cognitive impairment [28, 29]. The validity and reliability of the Flicker Fusion Test have been established [15, 30-34].

The Flicker Fusion Test was also performed with 10 repetitions to determine the flicker fusion frequency (using an electronic flicker fusion device, model RT-881, from Sina Iran Company) [35]. To conduct the Flicker Fusion Test, the subjects place their foreheads on the monitor of the light source device. Light with a frequency of 30 Hz is flashed into the subject’s eyes in a flickering manner. For each subject, 10 ascending and descending measurements are performed. In the ascending measurement, the light frequency increases from 30Hz until the subject perceives the moving light as fixed. The frequency at which the subject sees the flickering light as constant is recorded. In the descending test, the frequency of the constant light is reduced from 50Hz until the subject perceives the constant light as flickering. The frequency at which the subject sees the constant light as flickering is also recorded. The average of each ascending and descending test is calculated. The average of the 10 ascending and descending tests is referred to as the flicker fusion frequency, which is an important diagnostic criterion for determining the severity of cognitive impairment.

Phase 2: This phase involved reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex and evaluating physiological parameters. The modified WELkins EMT cooling device cover and skin temperature sensor were placed on the frontal skin area of both the intervention and control groups. For the intervention group, a cooling liquid with a constant temperature of 4°C flowed through the cooling device cover for 1 hour [23]. The cooling device was also applied to the forehead area of the control group, but the temperature of the liquid inside was 25°C (room temperature; sham). Physiological parameters, including blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, and sublingual temperature, were monitored and recorded at 0, 30, 45, and 60 minutes to ensure the safety of the intervention group and to examine changes in these parameters in both groups. Blood pressure and heart rate were measured using a portable wrist blood pressure monitor, Beurer BM47, while blood oxygen saturation was measured using a Beurer PO80 finger pulse oximeter at the end of this phase. A medical thermometer was used to assess sublingual temperature. The room temperature was maintained at a constant 25°C. If a participant reported a headache or discomfort, the temperature reduction process was stopped immediately, and the participant was referred to the team physician. This phase was supervised by a general practitioner.

Immediately after the one-hour prefrontal temperature reduction process, the cooling device cover was removed. Subjects in both groups then participated in the Rapid Visual Processing Test again. Following this test, the Flicker Fusion Test was administered to subjects in both groups to compare the severity of cognitive impairment in this phase with that of the first phase. To prevent bias and to account for the circadian rhythm of the subjects, the assessments for this phase and the first phase were conducted in one session and at the same time.

The double-blinding was done so that the principal investigator and the subjects in both groups were blinded to the type of intervention, and only the department head was aware of the type of intervention in each group.

The primary outcome was the patients’ visual attention accuracy and cognitive status, while the secondary outcomes included determining the correlation between visual attention accuracy and cognitive status, as well as assessing physiological parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen saturation percentage, and sublingual temperature of the patients.

SPSS 25 software was used to analyze the data. The normality of the quantitative data was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In the second phase, repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess changes in physiological parameters, including sublingual temperature, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and blood oxygen saturation. In both the first and second phases, paired t-tests, independent t-tests, and repeated measures ANOVA were used to compare the accuracy of visual attention and flicker fusion frequency before and after the intervention. Linear regression and the Pearson correlation coefficient were then calculated to examine the relationship between flicker fusion frequency and visual attention accuracy. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at less than 0.05.

Findings

Forty-two patients were analyzed, of whom 23 were male (54.76%) and 19 were female (45.24%). The mean age of the participants was 22.16±2.18 yaers. There was no significant difference in demographic factors, including gender, educational status, and marital status, between the intervention and control groups (p<0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics of participants

The average changes in the number of correct responses in the rapid visual processing test in the intervention group compared to the control group before the intervention were not significant (p=0.56). However, after the intervention, the average of these changes increased significantly in the intervention group compared to the control group (p=0.001). In the intra-group comparison using a paired t-test, the passage of time from the first phase to the second phase did not have a significant effect on the average change in the number of correct responses for the control group (p=0.059). In contrast, there was a significant increase in the average change in the number of correct responses after the intervention (p=0.001).

Additionally, there was no significant difference in flicker fusion frequency between the intervention and control groups before the intervention (p=0.72). However, after the intervention, there was a significant increase between the groups (p=0.001). In the intra-group comparison, there was no significant difference between the mean scores of the two time points in the control group, but in the intervention group, a significant increase was found in the mean scores before and after the intervention (p=0.001; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of mean visual attention accuracy and flicker fusion frequency between the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention

Linear regression analysis and the Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a direct relationship between flicker fusion frequency and the probability of correct responses in the Rapid Visual Processing Test in both phases and both groups (p<0.001). However, in the control group, a decrease in the probability of correct responses in the Rapid Visual Processing Test from the first to the second phase was accompanied by a significant decrease in flicker fusion frequency. Conversely, in the intervention group, the increase in the probability of correct responses in the rapid visual processing test was accompanied by a significant increase in flicker fusion frequency (p<0.001; Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation between flicker fusion frequency and visual attention accuracy in the rapid visual processing test in both groups before and after the intervention

At baseline, there was no significant difference in sublingual temperature between the two groups (p=0.112), but after 45, 30 and 60 minutes, there was a significant decrease in the sublingual temperature of the intervention group (p<0.001) and there was no significant difference in this regard in the control group (p>0.001).

For sublingual temperature, the interaction effect of time and intervention was not significant (p>0.13), so that in the control group, there was no significant change in sublingual temperature from the first phase to the second phase, but the effect of the intervention in the intervention group was still significant and led to a significant decrease in the sublingual temperature of the intervention group (p<0.001; Table 4).

Table 4. Comparisons of physiological parameters between the intervention and control groups by measurement time

However, for other physiological parameters, including heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure, the interaction between time and intervention was not significant (p>0.001). In addition, for both groups, there were no significant changes in mean heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and blood pressure in the second phase (p>0.001; Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of mean physiological parameters in each group

Discussion

The present study aimed to determine the effect of reducing the temperature of the frontal region on visual attention accuracy and cognitive status in patients with schizophrenia. Reducing the temperature of the frontal cortex led to a significant improvement in the accuracy of visual attention in patients in the intervention group. Immediately after the actual intervention, the number of correct responses in the rapid visual processing test in the second phase increased significantly compared to the first phase in the intervention group. In contrast, the number of correct responses in the control group decreased in the second phase compared to the first phase, although this decrease was not significant. These results are consistent with those of Lee et al., Jackson et al., and Mohsenian et al. [14, 18, 23]. However, these studies were conducted on normal, non-diseased individuals. As also observed in the results of the flicker fusion test, the decrease in the accuracy of sustained visual attention in the control group from the first phase to the second phase is attributed to cognitive weakness in the prefrontal cortex and subsequent dysfunction in the fronto-arthro.

As mentioned, the changes in visual attention accuracy in the intervention group after reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex are consistent with the studies by Jackson et al. and Mohsenian et al. [14, 23]. Although the study by Jackson et al. found a significant increase in correct responses to the 1-back test (a computer test to assess working memory) after reducing brain temperature in healthy individuals, no significant changes in reaction time were observed in other cognitive tests, such as the speed test, Stroop test, and 2-back test. Therefore, more studies on reducing brain temperature in both patients and healthy individuals are needed to determine the validity of these findings.

Lee et al. conducted a brain temperature reduction intervention on healthy individuals. Our results are also consistent with those of Lee et al., in which reducing the brain temperature of healthy individuals led to a decrease in reaction time in the psychomotor attention test and a decrease in the number of errors, although there was a slight improvement in the memory test [18]. The findings of Wang et al.’s study showed that cooling the whole body for 90 minutes in 10°C water led to changes in the neurophysiological activity of the brain, resulting in an increase in correct responses in the double-digit addition task, but there was no significant change in reaction time in the psychomotor attention test [24].

A few studies have been conducted in recent years to investigate the effect of reducing brain temperature on cognitive functions, including attention and memory. Most studies have examined the effectiveness of reducing brain temperature in increasing overall brain alertness in patients with stroke and traumatic brain injury, or in reducing surgical complications in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Fischer et al. demonstrated that reducing head temperature in patients with traumatic brain injury resulted in a significant increase in the Glasgow Coma Index during hospitalization [36]. Additionally, Poli et al. showed that reducing frontal head temperature led to an increase in the level of consciousness in stroke patients [37].

Flicker fusion frequency, as a valid indicator of the severity of cognitive impairment, indicated that attentional accuracy improved after reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex. Specifically, an increase in the number of correct responses in the Rapid Visual Processing Test in the second phase compared to the first phase was associated with a significant increase in flicker fusion frequency in the intervention group. Conversely, the control group exhibited a significant decrease in flicker fusion frequency in the second phase compared to the first phase. The changes in the mean flicker fusion frequency in the present study are consistent with the results of Coull et al. and Lim et al. [38, 39]. There was a direct correlation in both groups across both phases. Therefore, this finding, along with previous studies, can enhance the validity of the Flicker Fusion test in determining the severity of cognitive weakness or fatigue.

Luczak et al. found that after visual focus during a 15-minute cognitive task, the values of flicker fusion frequency decreased from 0.5 to 6Hz, indicating cognitive impairment [28]. Additionally, in the study by Ma et al., the mean flicker fusion frequency decreased to 2.16 Hz after performing a visual search test for 10 minutes [29]. The changes in flicker fusion frequency from the second phase to the first phase are consistent with the studies of Luczak et al. and Ma et al.

The reduction in prefrontal cortex temperature led to significant changes in sublingual temperature during the intervention periods in the intervention group, which is consistent with the results of Mohsenian et al. [14]. In contrast, the study by Jackson et al. observed no significant changes in sublingual temperature [23]. This difference is likely related to both the method used for reducing brain temperature and its effects on physiological parameters, as well as the characteristics of the target group studied. In the study by Jackson et al., the reduction in brain temperature resulted in significant changes in inner ear temperature; however, due to a lack of the necessary tools, the assessment of inner ear temperature was not conducted in the present study.

There were no significant changes in heart rate and blood pressure between the two groups. Additionally, there were no significant changes in blood oxygen saturation between the two groups, indicating normal blood oxygen saturation levels during brain temperature reduction. These results are consistent with those of Mohsenian et al. and Jackson et al. [14, 23]. Kallmünzer et al. showed that the rectal and inner ear temperatures of normal subjects decreased significantly during 60 minutes of brain temperature reduction, but there were no significant changes in heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, or blood oxygen saturation, and the conditions were tolerable and suitable for the subjects, which is consistent with our study [27]. Wang et al. demonstrated that if head and neck cooling is continued for more than 120 minutes in athletes with a history of head trauma, it can increase systolic and diastolic blood pressure by more than 15mmHg [40]. Furthermore, Walter et al. and Ku et al. showed that head and neck cooling for 30 minutes does not cause significant changes in body temperature [35, 16]. Subjects in the intervention group did not report any discomfort, such as headaches or dizziness, during the 60-minute reduction in brain temperature, which is consistent with the studies by Jackson et al., Walter et al., Kallmünzer et al., and Ku et al. [35,16, 23, 27].

Among the strengths of this research are the procedures performed under controlled conditions, with the patient hospitalized in a hospital ward and under the supervision of a physician, as well as the use of advanced devices and a team of expert medical specialists to carry out the various phases of the study, including data analysis (for example, the use of a sensitive electronic flicker fusion device to assess the severity of cognitive impairment by an expert user). This study also had limitations, including the lack of a brain wave measuring device to examine the activity of the prefrontal cortex and the frontoparietal neural network during the rapid visual processing test. Additionally, the absence of an intracranial sensor to more accurately examine changes in the temperature of the cerebral cortex and the inability to assess the long-term effects of reducing brain temperature on cognitive skills were other limitations.

Reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex led to improved visual attention accuracy and cognitive function in schizophrenia patients in the intervention group. Since the prefrontal cortex plays an important role in the fronto-parietal neural network—and as mentioned, one of the functions of this network is to control visual attention—it can be concluded that reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex resulted in decreased blood flow in this area and, subsequently, changes in the neurophysiological activity of the visual attention neural network in schizophrenia patients, which favored the improvement of visual attention accuracy. The existence of a significant relationship between changes in flicker fusion frequency supports this conclusion. From the relationship between the probability of correct responses in the rapid visual processing test and flicker fusion frequency, it can be concluded that the improvement of cognitive skills in schizophrenia patients is inversely related to cognitive impairment. It can also be concluded that the reduction in blood flow in the prefrontal cortex of these patients, following a decrease in the temperature of this area, has led to a decrease in the severity of cognitive impairment in the frontoparietal neural network and, subsequently, an improvement in performance on the rapid visual processing test. No significant changes in physiological parameters were observed that would negatively impact health during the reduction of the temperature of the prefrontal cortex. Therefore, considering the results of recent studies alongside the present study, as well as the importance of choosing non-invasive methods to improve the cognitive skills of schizophrenia patients while they perform cognitive tasks, it can be concluded that reducing the temperature of the prefrontal cortex is an effective and safe method for enhancing certain cognitive skills, including visual attention span. Further studies on the effect of reducing brain temperature on other cognitive skills, such as problem-solving and reaction time, as well as on physical and motor skills, such as catatonia, are recommended.

Conclusion

Cooling the prefrontal cortex effectively modulates cerebral blood flow and neurophysiological activity, leading to improved attention and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Yasuj University of Medical Sciences and the Research Department of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences for their cooperation in approving and implementing this plan. We also appreciate the cooperation of Dr. Sadati, Head of the Neurotherapy and Occupational Therapy Department at Shahid Rajaee Hospital, and the patients who participated in this study. The study was registered with the International Center for the Registration of Clinical Trials of Iran (IRCT20250119064433N1).

Ethical permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences under the code IR.YUMS.REC.1403.076.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Author’s Contribution: Mohsenian S (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Yazdanpanah I (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Hashemimohammadabad N (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Sadat Z (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Hashemimohammadabad Z (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: This article was extracted from Zahra Sadat’s thesis in medicine and was supported by Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

Keywords:

References

1. Wass C. Cognition and social behavior in schizophrenia an animal model investigating the potential role of nitric oxide. Sweden: Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology; 2007. [Link]

2. Keshavan MS, Diwadkar VA, Montrose DM, Rajarethinam R, Sweeney JA. Premorbid indicators and risk for schizophrenia: A selective review and update. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):45-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.004]

3. Grier RA, Warm JS, Dember WN, Matthews G, Galinsky TL, Parasuraman R. The vigilance decrement reflects limitations in effortful attention, not mindlessness. Hum Factors. 2003;45(3):349-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1518/hfes.45.3.349.27253]

4. Wan Q, Ten Oever S, Sack AT, Schuhmann T. Enhancing cognitive performance with fronto-parietal transcranial alternating current stimulation. Biol Psychol. 2025;200:109111. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2025.109111]

5. Cook AJ, Im HY, Giaschi DE. Large-scale functional networks underlying visual attention. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2025;173:106165. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106165]

6. Murray EA, Wise SP, Graham KS. The evolution of memory systems: Ancestors, anatomy, and adaptations. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199686438.001.0001]

7. DeYoung CG, Hirsh JB, Shane MS, Papademetris X, Rajeevan N, Gray JR. Testing predictions from personality neuroscience: Brain structure and the big five. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(6):820-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0956797610370159]

8. Yang Y, Raine A. Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2009;174(2):81-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.012]

9. Sellers KK, Yu C, Zhou ZC, Stitt I, Li Y, Radtke-Schuller S, et al. Oscillatory dynamics in the frontoparietal attention network during sustained attention in the ferret. Cell Rep. 2016;16(11):2864-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.055]

10. Kobayashi Y, Asai T, Yoshihara Y, Yamashita M, Nakamura H, Shimizu M, et al. Enhancement of the left frontoparietal network through real-time functional magnetic resonance imaging functional connectivity-informed neurofeedback and its impact on working memory in schizophrenia: A pilot study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2025;79(9):531-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/pcn.13849]

11. Shigihara Y, Tanaka M, Ishii A, Kanai E, Funakura M, Watanabe Y. Two types of mental fatigue affect spontaneous oscillatory brain activities in different ways. Behav Brain Funct. 2013;9:2. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1744-9081-9-2]

12. Ishii A, Tanaka M, Shigihara Y, Kanai E, Funakura M, Watanabe Y. Neural effects of prolonged mental fatigue: A magnetoencephalography study. Brain Res. 2013;1529:105-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.brainres.2013.07.022]

13. Tanaka M, Ishii A, Watanabe Y. Neural effects of mental fatigue caused by continuous attention load: A magnetoencephalography study. Brain Res. 2014;1561:60-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.03.009]

14. Mohsenian S, Kouhnavard B, Nami M, Mehdizadeh A, Seif M, Zamanian Z. Effect of temperature reduction of the prefrontal area on accuracy of visual sustained attention. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2023;29(4):1368-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10803548.2022.2131116]

15. Balestra C, Machado ML, Theunissen S, Balestra A, Cialoni D, Clot C, et al. Critical flicker fusion frequency: A marker of cerebral arousal during modified gravitational conditions related to parabolic flights. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1403. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fphys.2018.01403]

16. Walter A, Finelli K, Bai X, Johnson B, Neuberger T, Seidenberg P, et al. Neurobiological effect of selective brain cooling after concussive injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(3):891-900. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11682-017-9755-2]

17. Harris B, Andrews PJ, Murray GD, Forbes J, Moseley O. Systematic review of head cooling in adults after traumatic brain injury and stroke. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(45):1-175. [Link] [DOI:10.3310/hta16450]

18. Lee JK, Koh AC, Koh SX, Liu GJ, Nio AQ, Fan PW. Neck cooling and cognitive performance following exercise-induced hyperthermia. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(2):375-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00421-013-2774-9]

19. Titus DJ, Furones C, Atkins CM, Dietrich WD. Emergence of cognitive deficits after mild traumatic brain injury due to hyperthermia. Exp Neurol. 2015;263:254-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.10.020]

20. Ponz I, Lopez-de-Sa E, Armada E, Caro J, Blazquez Z, Rosillo S, et al. Influence of the temperature on the moment of awakening in patients treated with therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;103:32-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.03.017]

21. Wood T, Osredkar D, Puchades M, Maes E, Falck M, Flatebo T, et al. Treatment temperature and insult severity influence the neuroprotective effects of therapeutic hypothermia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23430. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/srep23430]

22. Arrica M, Bissonnette B. Therapeutic hypothermia. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;11(1):6-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1089253206297409]

23. Jackson K, Rubin R, Van Hoeck N, Hauert T, Lana V, Wang H. The effect of selective head-neck cooling on physiological and cognitive functions in healthy volunteers. Transl Neurosci. 2015;6(1):131-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1515/tnsci-2015-0012]

24. Wang H, Olivero W, Lanzino G, Elkins W, Rose J, Honings D, et al. Rapid and selective cerebral hypothermia achieved using a cooling helmet. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(2):272-7. [Link] [DOI:10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0272]

25. Koehn J, Kollmar R, Cimpianu CL, Kallmunzer B, Moeller S, Schwab S, et al. Head and neck cooling decreases tympanic and skin temperature, but significantly increases blood pressure. Stroke. 2012;43(8):2142-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.652248]

26. Keller E, Mudra R, Gugl C, Seule M, Mink S, Frohlich J. Theoretical evaluations of therapeutic systemic and local cerebral hypothermia. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;178(2):345-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.12.030]

27. Kallmünzer B, Beck A, Schwab S, Kollmar R. Local head and neck cooling leads to hypothermia in healthy volunteers. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(3):207-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1159/000329376]

28. Luczak A, Sobolewski A. Longitudinal changes in critical flicker fusion frequency: an indicator of human workload. Ergonomics. 2005;48(15):1770-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00140130500241753]

29. Ma J, Ma RM, Liu XW, Bian K, Wen ZH, Li XJ, et al. Workload influence on fatigue related psychological and physiological performance changes of aviators. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87121. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0087121]

30. Mewborn C, Renzi LM, Hammond BR, Miller LS. Critical flicker fusion predicts executive function in younger and older adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;30(7):605-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/arclin/acv054]

31. Kogi K, Saito Y. A factor-analytic study of phase discrimination in mental fatigue. Ergonomics. 1971;14(1):119-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00140137108931230]

32. Rammsayer T. Extraversion and alcohol: Eysenck's drug postulate revisited. Neuropsychobiology. 1995;32(4):197-207. [Link] [DOI:10.1159/000119236]

33. Wooten BR, Renzi LM, Moore R, Hammond BR. A practical method of measuring the human temporal contrast sensitivity function. Biomed Opt Express. 2010;1(1):47-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1364/BOE.1.000047]

34. Hammond BR, Wooten BR. CFF thresholds: Relation to macular pigment optical density. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2005;25(4):315-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00271.x]

35. Ku YT, Montgomery LD, Webbon BW. Hemodynamic and thermal responses to head and neck cooling in men and women. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;75(6):443-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00002060-199611000-00008]

36. Fischer M, Lackner P, Beer R, Helbok R, Klien S, Ulmer H, et al. Keep the brain cool--endovascular cooling in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: A case series study. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(4):867-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1227/NEU.0b013e318208f5fb]

37. Poli S, Purrucker J, Priglinger M, Diedler J, Sykora M, Popp E, et al. Induction of cooling with a passive head and neck cooling device: Effects on brain temperature after stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(3):708-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.672923]

38. Coull JT, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD. Monitoring for target objects: Activation of right frontal and parietal cortices with increasing time on task. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36(12):1325-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0028-3932(98)00035-9]

39. Lim J, Wu WC, Wang J, Detre JA, Dinges DF, Rao H. Imaging brain fatigue from sustained mental workload: An ASL perfusion study of the time-on-task effect. NeuroImage. 2010;49(4):3426-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.020]

40. Wang H, Wang B, Jackson K, Miller CM, Hasadsri L, Llano D, et al. A novel head-neck cooling device for concussion injury in contact sports. Transl Neurosci. 2015;6(1):20-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1515/tnsci-2015-0004]