Volume 6, Issue 4 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(4): 177-183 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.IAU.SARI.REC.1403.428

History

Received: 2025/08/13 | Accepted: 2025/09/26 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2025/08/13 | Accepted: 2025/09/26 | Published: 2025/10/1

How to cite this article

Hamidi B, Ghanadzadegan H, Mirzaian B. Effect of Solution-Focused Child Skills Training and Acceptance and Commitment-Based Play Therapy on Social Competence in Anxious Children. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (4) :177-183

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-441-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-441-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Psychology, Sari Campus (Sar.C.), Islamic Azad University, Sari, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (113 Views)

Introduction

The foundational role of children within the family and community necessitates careful attention to and resolution of the challenges they face. Among the issues that profoundly affect the mental well-being of children, problems stemming from anxiety are particularly notable [1]. The prevalence of anxiety is reported to be substantial in school-age populations, with figures suggesting a rate of 28.8% [2]. Elevated levels of anxiety trigger numerous detrimental outcomes, including acute discomfort at school, distraction, impaired ability to store information in short-term memory, inefficient processing of thoughts, and frequently lead to school avoidance or refusal to complete homework assignments [3]. The presence of an anxiety disorder is considered a key indicator of unhealthy behaviors in children and can result in significant negative consequences. One of the critical outcomes of such issues is a deficient sense of social competence in the child [4]. Given these adverse impacts, addressing anxiety and its resulting functional impairments remains a paramount concern for researchers and practitioners in child psychology.

Social competence is a vital attribute for children, fostering the establishment of positive relationships with others, enabling more accurate and age-appropriate social cognition, and promoting adaptive and effective social behaviors [5]. This multifaceted construct is generally understood to comprise four dimensions, including cognitive Skills, which include a reservoir of information, information processing and acquisition skills, decision-making ability, the functionality of beliefs, and attributional styles, behavioral skills, encompassing negotiation, role-playing, assertiveness, and conversational skills necessary for initiating and sustaining social interactions, as well as learning and acquiring knowledge and demonstrating kindness toward others, Emotional-Affective Skills, which are essential for building positive relationships, developing and expanding mutual trust and supportive bonds, identifying and responding appropriately to emotional cues during social exchanges, and managing stress; and motivational skills, involving an individual’s value structure, moral development level, sense of efficacy and control, and ultimately, self-efficacy [6, 7].

Research consistently demonstrates a significant negative correlation between social competence and generalized anxiety disorder among students [8, 9]. As social competence increases, the severity of generalized anxiety disorder decreases. Consequently, a school environment that generates anxiety can worsen a child’s academic and social functioning [10]. Therefore, timely intervention is essential to prevent the exacerbation of anxiety and to bolster social competency.

Given the crucial role of skill training in children’s mental health, employing therapeutic approaches that are both engaging and highly effective is critical. One such innovative approach is solution-focused child skills training (SFCST). Developed by Ben Furman, this method diverges from directly addressing problems or prescribing solutions; instead, it centers on the child’s inherent abilities and resources [11]. The application of this method in working with children facilitates a shift in focus from the perceived problem to the acquisition of necessary skills and the achievement of positive outcomes [12]. A key advantage of SFCST is its emphasis on collaborating with the child by respecting their perspective, focusing on the absence of the problem, and enhancing cooperation by teaching new, necessary skills through enjoyable and rewarding methods [13]. Previous studies have confirmed the efficacy of SFCST, finding it aligned with research by Khavari Khorasani et al. [12] and Vatankhah et al. [14].

In contrast, some child therapists argue that children lack the verbal capacity of adults to fully express their feelings and emotions. This belief underpins non-directive methods, such as play therapy, where toys and play serve as the child’s language, enabling self-expression and emotional discharge [15, 16]. While most traditional play therapies are based on second-wave cognitive-behavioral treatments, third-wave psychotherapies, including acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), have seen a growing trend in the field of psychotherapy [17]. ACT involves mindfulness-based exercises, linguistic metaphors, and techniques like mental care [18]. The core objective of this treatment is to establish the child’s capacity to choose actions that are more adaptive, rather than actions driven by the avoidance of distressing thoughts, feelings, memories, or urges—a concept known as cognitive flexibility [19]. Research on ACT-based play therapy (ACPT) supports its utility, with studies by Ghorbanikhah et al. [20] demonstrating its ability to improve parent-child interaction and attachment in children aged 6 to 9 with separation anxiety. Similarly, Mortazavi et al. [21] showed that ACT-based play therapy significantly increases self-esteem and self-efficacy in elementary students.

Despite evidence supporting both SFCST and ACPT, a direct comparative study on their effectiveness in a specific at-risk population, such as anxious children, has been notably absent in the literature. Given the importance of training and intervention for the mental health of anxious children and the necessity of focusing on components like social competence in this population, there is a clear need to determine which approach yields superior results. Therefore, this research was undertaken with the objective of comparing the efficacy of SFCST and ACPT on the social competence of anxious children. The findings aim to provide evidence-based guidance for clinicians and educators in selecting the most impactful intervention for this vulnerable group.

Materials and Methods

Research design and participants

The current clinical trial employed a quasi-experimental design with a pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up structure, along with a control group. This design was selected to compare the efficacy of two distinct therapeutic interventions on the dependent parameter. The statistical population (target population) comprised all anxious children aged 9 to 12 years attending elementary schools in District 5 of Tehran during the 2024-2025 academic year.

The sample size was determined a priori using G*Power 3.1 software for a repeated measures ANOVA, specifically the within-between interaction test family (F tests). Parameters included a medium effect size (f=0.25), α=0.05, statistical power=0.80, number of groups=3 (between-subjects factor), number of measurements=3 (within-subjects factor, df=2), correlation among repeated measures=0.50 (a conservative estimate for short-term follow-up in child interventions), and nonsphericity correction ε=1. This calculation yielded a minimum required sample size of 18 participants per group (total N=54). To accommodate an anticipated attrition rate of up to 10% (common in pediatric psychological trials due to session absences or family withdrawals), recruitment targeted 20 participants per group (total N=60), resulting in the final sample exceeding the powered minimum. A total of 60 female students who met the inclusion criteria were selected using convenience sampling (a purposeful selection followed by simplified random allocation) and subsequently assigned using simple random assignment into three groups (n=20 per group): the SFCST group, the ACPT group, and the control group.

Inclusion criteria for participants were being female and between 9 and 12 years old, receiving a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder from a child and adolescent specialist (psychiatrist or clinical psychologist), not receiving any other concurrent psychological treatment, and obtaining a score indicating below-average social competence on the Social Competence Scale. Exclusion criteria included being absent for more than two intervention sessions, receiving any other therapeutic intervention during the study period, and developing a major psychiatric disorder. No participants were lost to follow-up, resulting in full retention across all groups (0% attrition), which enhanced the study’s statistical power beyond initial estimates. Ethical considerations were strictly observed. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants after they were fully informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, and their right to withdraw at any point without penalty. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured for all data collected.

Instrument

Social Competence Scale-Parent Version (SCS-P)

The SCS-P was employed to measure the dependent parameter. This instrument consists of 12 items designed to assess the child’s social competence, as observed and reported by their parents. The scale utilizes a 5-point Likert-type format ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). The total score ranges from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating a higher level of social competence. The scale comprises two subscales: social/communication skills (items 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12) and emotional regulation skills (items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8). In previous Iranian studies, the SCS-P has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties [22]. For instance, in the research conducted by Gouley et al. [23], the internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for the Persian version was reported as 0.86. In the current study, after translation and back-translation to ensure linguistic equivalence, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated to be 0.88, confirming its high internal consistency and reliability for use with the Iranian student population.

Procedure

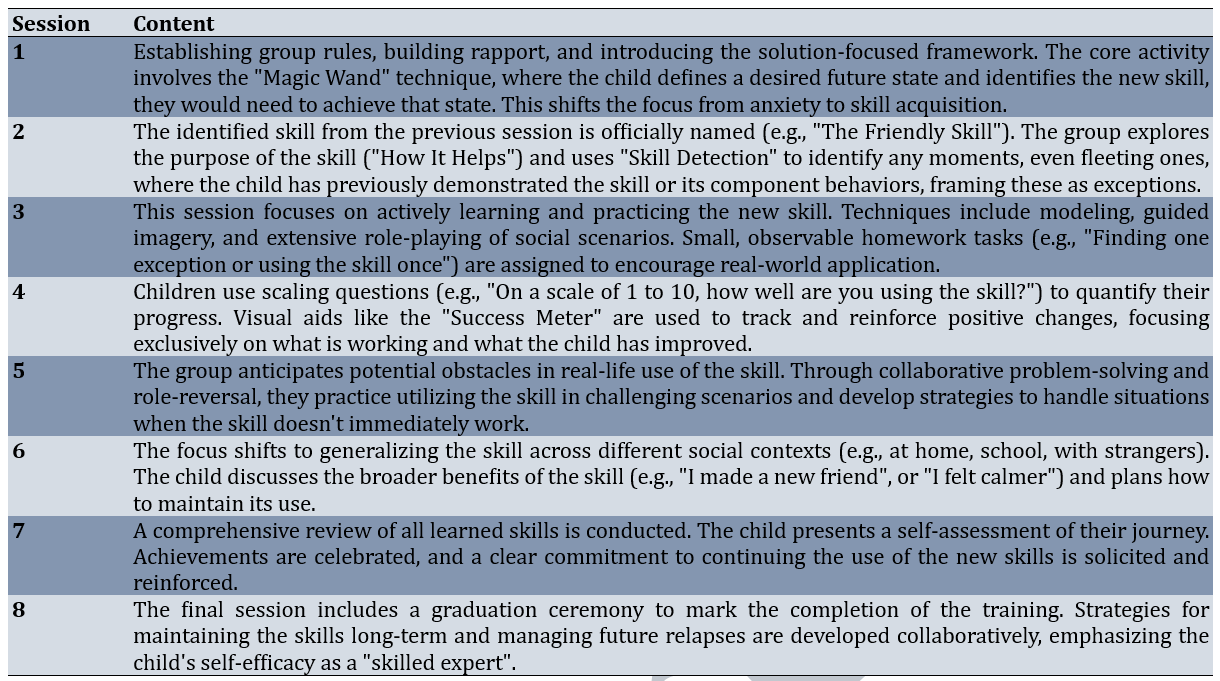

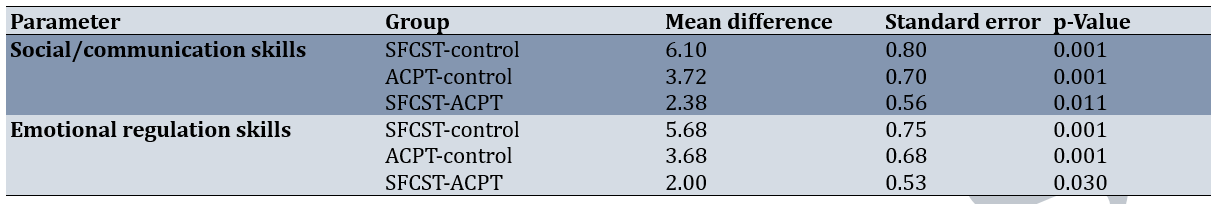

Data collection involved administering the SCS-P to all three groups at three time points: pre-test, post-test (immediately after the final session), and at a three-month follow-up. The two experimental groups received their respective intervention protocols over eight 60-minute sessions, administered once per week. The protocols were implemented by a trained clinical psychologist. The control group received no intervention during this period but was offered one of the interventions after the completion of the follow-up phase. The SFCST protocol was adapted from the work of Furman [11] and focused on teaching new skills rather than dwelling on the problems caused by anxiety (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of solution-focused child skills training (SFCST) sessions

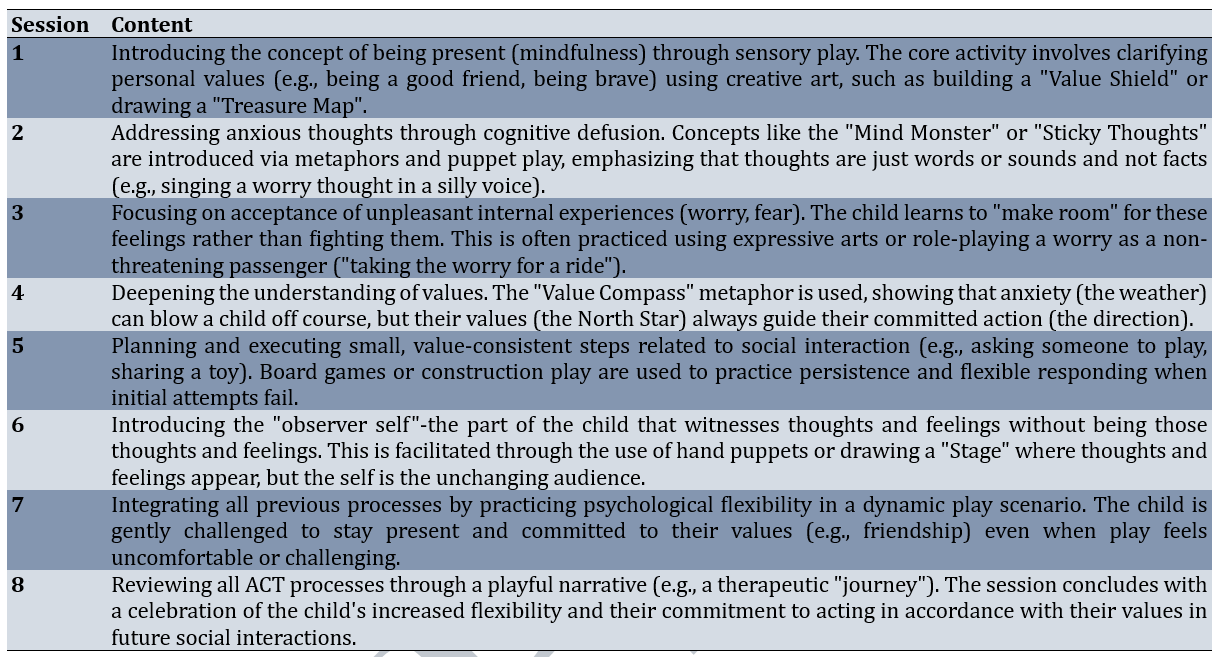

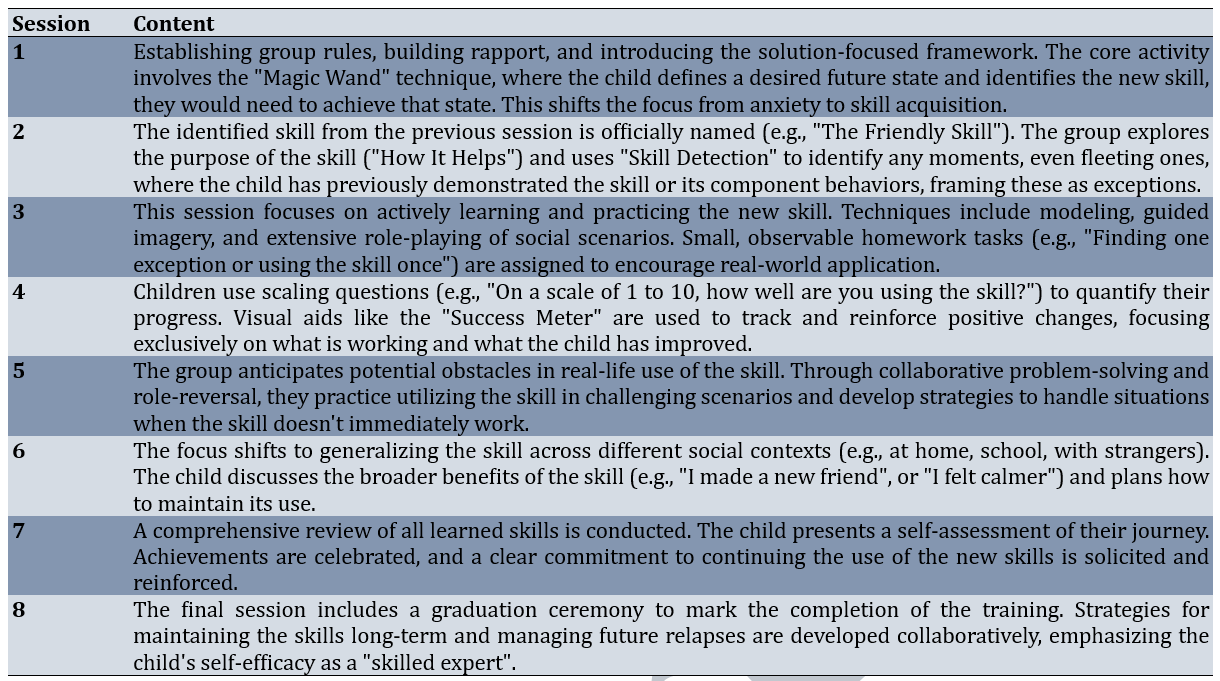

The ACPT protocol was designed based on the core processes of ACT, emphasizing psychological flexibility through engaging in play activities (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of acceptance and commitment-based play therapy (ACPT) sessions

Data analysis

The data collected across the three time points (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up) were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) by SPSS 26. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were subsequently utilized to identify specific statistically significant differences between the three groups.

Findings

The study sample comprised 60 female children aged 9-12 years (10.6±1.0) diagnosed with anxiety disorders. All participants were of Persian ethnicity, with no significant baseline differences across groups in age (F=0.42, p=0.664) or socioeconomic status (χ²=3.21, p=0.522), ensuring group comparability.

At baseline, all groups exhibited below-average social competence levels, with comparable means. Post-intervention, both experimental groups showed substantial gains, particularly the SFCST group, while the control group remained stable. These improvements were largely maintained at follow-up, indicating potential durability of effects (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean scores for social/communication skills, emotional regulation skills, and total social competence across groups and time points

Prior to conducting the repeated measures ANOVA, key statistical assumptions were assessed to ensure robustness. Normality of residuals was confirmed via Shapiro-Wilk tests (all p>0.05 across groups and time points). Homogeneity of variances was verified with Levene’s test (p>0.05 for group and time interactions), and sphericity was upheld by Mauchly’s test (χ²<3.12, p>0.05; Greenhouse-Geisser correction applied where ε<0.75, though unnecessary here). These validations supported the parametric approach, minimizing type I error inflation.

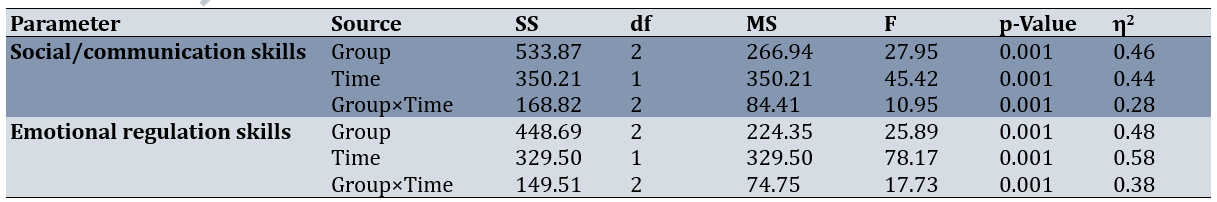

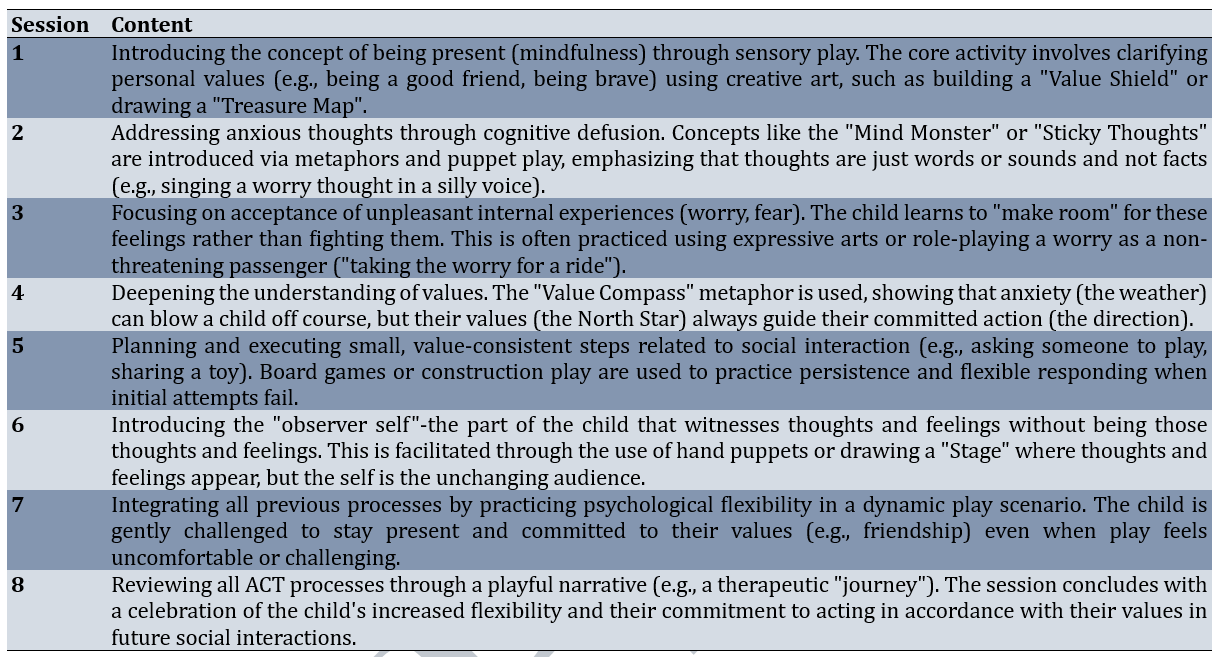

The repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects for group (social/communication: F(2, 57)=27.95, p<0.001, η²=0.46; emotional regulation: F(2, 57)=25.89, p<0.001, η²=0.48) and time (social/communication: F(1, 57)=45.42, p<0.001, η²=0.44; emotional regulation: F(1, 57)=78.17, p<0.001, η²=0.58), alongside robust group×time interactions (social/communication: F(2, 114)=10.95, p<0.001, η²=0.28; emotional regulation: F(2, 114)=17.73, p<0.001, η²=0.38; Table 4).

Table 4. Repeated measures ANOVA results for social/communication skills and emotional regulation skills

Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc tests for time effects confirmed significant improvements from pre-test to post-test and from pre-test to follow-up across all parameters. Notably, no significant differences emerged between post-test and follow-up (social/communication, evidencing the stability of gains over three months (Table 5).

Table 5. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons for time effects on social/communication skills and emotional regulation skills

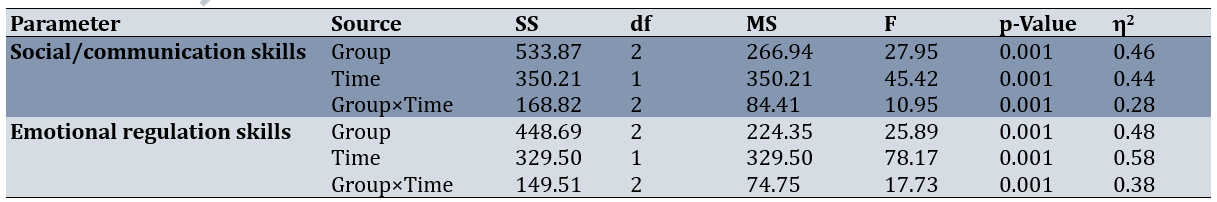

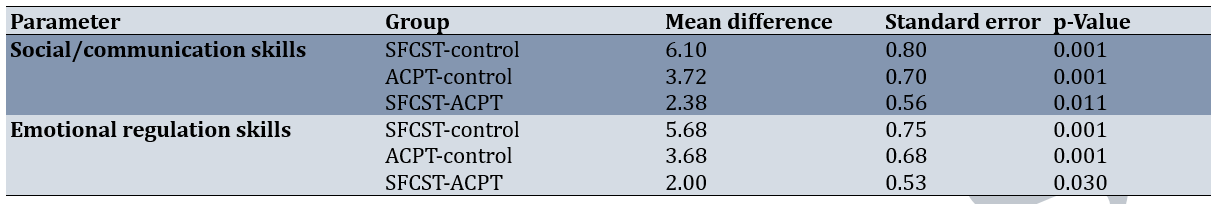

Pairwise group comparisons via Bonferroni correction at post-test highlighted the superiority of both interventions over the control, with SFCST demonstrating the largest effects. For social/communication skills, SFCST outperformed the control (p<0.001) and ACPT (p=0.002), while ACPT also exceeded the control (p<0.001). Similarly, for emotional regulation skills, SFCST surpassed the control (p<0.001) and ACPT (p=0.030), with ACPT being superior to the control (p<0.001; Table 6). These targeted contrasts affirm SFCST’s enhanced efficacy, particularly in fostering adaptive social behaviors among anxious children.

Table 6. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons for group effects on social/communication skills and emotional regulation skills (post-test)

Discussion

This investigation sought to conduct a comparative evaluation of SFCST and ACPT in augmenting social competence among children diagnosed with anxiety disorders. Both interventions engendered statistically significant enhancements in social competence, as measured across the domains of social/communication skills and emotional regulation skills, when benchmarked against the control condition. Of paramount importance, however, is the unequivocal demonstration that SFCST exhibited superior efficacy, manifesting in larger effect sizes relative to ACPT across both subscales and the composite score. Moreover, the post-intervention advancements were robustly maintained at the three-month follow-up, with negligible decay in mean scores, thereby attesting to the longitudinal stability of these therapeutic modalities.

The preeminence of SFCST in this context may be ascribed to its paradigmatically structured, goal-directed, and resource-centric orientation, which resonates profoundly with the developmental exigencies of anxious youth. Children grappling with anxiety frequently exhibit patterns of cognitive evasion and interpersonal reticence, which SFCST adeptly circumvents by pivoting attention toward skill development and the conceptual “absence of the problem” [24]. This methodological shift not only demystifies anxiety-related deficits as surmountable skill gaps but also mitigates the ruminative cycles endemic to such disorders through the provision of discrete, empirically reinforced behavioral scaffolds [25]. Consequently, SFCST facilitates a teleological progression from deficit identification to mastery, fostering adaptive social repertoires with heightened immediacy and transferability. These observations converge seamlessly with extant scholarship affirming SFCST’s significance in psychosocial skill enhancement. For instance, Vatankhah et al. [14] empirically corroborate the modality’s effectiveness in improving life and communication skills among children with intellectual disabilities, underscoring its versatility across neurodevelopmental spectra. Analogously, Soderqvist et al. [26] illuminate the efficacy of solution-focused paradigms in elevating multifaceted social indices among adolescents, thereby extending the generalizability of these benefits to similar age cohorts and contextualizing the present outcomes within a broader evidence base.

Notwithstanding SFCST’s ascendancy, the salutary impact of ACPT in comparison to the control group (evidenced by moderate effect sizes affirms the viability of amalgamating third-wave cognitive-behavioral tenets (specifically, ACT) with the ontogenetically attuned medium of play. At its core, ACPT operationalizes psychological flexibility as the fulcrum for value-congruent behavior amid aversive internal states [27], leveraging playful metaphors to disentangle children from maladaptive cognitive attachments and normalize the accommodation of emotional turbulence [20]. This experiential scaffold thereby mitigates avoidance-driven impediments to social engagement, cultivating a relational resilience consonant with anxiety’s etiological underpinnings. Such affirmations echo contemporary inquiries; notably, Mortazavi et al. [21] indicate ACPT’s enhancement of self-esteem and self-efficacy in elementary-aged cohorts, paralleling the emotional regulation gains observed herein. In tandem, Ahmadvand & Ahmadi Kohanali [28] demonstrate improvements in dyadic parent-child dynamics and attachment security among youth with separation anxiety, thereby reinforcing ACPT’s relational affordances and illuminating its synergistic potential with familial contexts.

The persistence of therapeutic gains over the three-month surveillance interval constitutes a clinically relevant hallmark, suggesting that the latent mechanisms (whether SFCST’s behavioral reinforcement cascades or ACPT’s paradigmatic reorientation toward value-driven action) have been sufficiently consolidated to withstand temporal attrition. This durability aligns with theoretical postulates positing that skill-based interventions promote procedural memory consolidation, whereas flexibility-oriented approaches recalibrate metacognitive schemas, both of which are conducive to prolonged protection against anxiety’s social sequelae [17, 19].

From a practical standpoint, these delineations offer valuable guidance for clinicians navigating pediatric anxiety interventions. SFCST emerges as the preferred strategy for scenarios demanding rapid, measurable behavioral gains, particularly within resource-constrained educational settings. Conversely, ACPT’s experiential ethos may be better suited for younger or verbally reticent children, where play mediates access to abstract constructs. Integratively, hybrid protocols warrant exploration to harness complementary synergies, potentially amplifying outcomes in heterogeneous anxiety presentations.

Notwithstanding these advancements, interpretive caveats are warranted. The use of convenience sampling limited the cohort to female elementary students within a single urban precinct, thereby reducing external validity and precluding inferences about male, rural, or transcultural populations. Furthermore, the parent-proxy assessment via the SCS-P, while psychometrically robust, may introduce reporter bias, potentially underestimating or overestimating child-reported competencies. The quasi-experimental design, lacking full randomization, invites residual confounds from baseline heterogeneity, although this is mitigated by pre-test equivalences. Additionally, the eight-session cadence, while pragmatic, restricts the examination of dose-response dynamics or longer-term trajectories beyond three months.

Prospective inquiries might address these gaps through multisite, randomized controlled trials encompassing diverse demographics and incorporating multimodal assessments (e.g., child self-reports, observational metrics). Longitudinal extensions to one-year intervals would elucidate relapse prevention, while dismantling studies could parse constituent mechanisms (e.g., skill mastery vs. defusion). Ultimately, cost-effectiveness analyses would inform scalable dissemination, embedding these modalities within tiered school-based mental health frameworks to mitigate anxiety’s societal toll.

Conclusion

Both SFCST and ACPT are effective therapeutic interventions for enhancing the social competence of anxious children.

Acknowledgments: The researchers wish to thank all the individuals who participated in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This study obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Sari Branch, Iran (Approval No.: IR.IAU.SARI.REC.1403.428; IRCT Registration: IRCT20250429065530N1), thereby adhering to established ethical protocols.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interests to declare.

Authors' Contribution: Hamidi B (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Ghanadzadegan HA (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Mirzaian B (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%)

Funding/Support: This study did not receive any funding.

The foundational role of children within the family and community necessitates careful attention to and resolution of the challenges they face. Among the issues that profoundly affect the mental well-being of children, problems stemming from anxiety are particularly notable [1]. The prevalence of anxiety is reported to be substantial in school-age populations, with figures suggesting a rate of 28.8% [2]. Elevated levels of anxiety trigger numerous detrimental outcomes, including acute discomfort at school, distraction, impaired ability to store information in short-term memory, inefficient processing of thoughts, and frequently lead to school avoidance or refusal to complete homework assignments [3]. The presence of an anxiety disorder is considered a key indicator of unhealthy behaviors in children and can result in significant negative consequences. One of the critical outcomes of such issues is a deficient sense of social competence in the child [4]. Given these adverse impacts, addressing anxiety and its resulting functional impairments remains a paramount concern for researchers and practitioners in child psychology.

Social competence is a vital attribute for children, fostering the establishment of positive relationships with others, enabling more accurate and age-appropriate social cognition, and promoting adaptive and effective social behaviors [5]. This multifaceted construct is generally understood to comprise four dimensions, including cognitive Skills, which include a reservoir of information, information processing and acquisition skills, decision-making ability, the functionality of beliefs, and attributional styles, behavioral skills, encompassing negotiation, role-playing, assertiveness, and conversational skills necessary for initiating and sustaining social interactions, as well as learning and acquiring knowledge and demonstrating kindness toward others, Emotional-Affective Skills, which are essential for building positive relationships, developing and expanding mutual trust and supportive bonds, identifying and responding appropriately to emotional cues during social exchanges, and managing stress; and motivational skills, involving an individual’s value structure, moral development level, sense of efficacy and control, and ultimately, self-efficacy [6, 7].

Research consistently demonstrates a significant negative correlation between social competence and generalized anxiety disorder among students [8, 9]. As social competence increases, the severity of generalized anxiety disorder decreases. Consequently, a school environment that generates anxiety can worsen a child’s academic and social functioning [10]. Therefore, timely intervention is essential to prevent the exacerbation of anxiety and to bolster social competency.

Given the crucial role of skill training in children’s mental health, employing therapeutic approaches that are both engaging and highly effective is critical. One such innovative approach is solution-focused child skills training (SFCST). Developed by Ben Furman, this method diverges from directly addressing problems or prescribing solutions; instead, it centers on the child’s inherent abilities and resources [11]. The application of this method in working with children facilitates a shift in focus from the perceived problem to the acquisition of necessary skills and the achievement of positive outcomes [12]. A key advantage of SFCST is its emphasis on collaborating with the child by respecting their perspective, focusing on the absence of the problem, and enhancing cooperation by teaching new, necessary skills through enjoyable and rewarding methods [13]. Previous studies have confirmed the efficacy of SFCST, finding it aligned with research by Khavari Khorasani et al. [12] and Vatankhah et al. [14].

In contrast, some child therapists argue that children lack the verbal capacity of adults to fully express their feelings and emotions. This belief underpins non-directive methods, such as play therapy, where toys and play serve as the child’s language, enabling self-expression and emotional discharge [15, 16]. While most traditional play therapies are based on second-wave cognitive-behavioral treatments, third-wave psychotherapies, including acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), have seen a growing trend in the field of psychotherapy [17]. ACT involves mindfulness-based exercises, linguistic metaphors, and techniques like mental care [18]. The core objective of this treatment is to establish the child’s capacity to choose actions that are more adaptive, rather than actions driven by the avoidance of distressing thoughts, feelings, memories, or urges—a concept known as cognitive flexibility [19]. Research on ACT-based play therapy (ACPT) supports its utility, with studies by Ghorbanikhah et al. [20] demonstrating its ability to improve parent-child interaction and attachment in children aged 6 to 9 with separation anxiety. Similarly, Mortazavi et al. [21] showed that ACT-based play therapy significantly increases self-esteem and self-efficacy in elementary students.

Despite evidence supporting both SFCST and ACPT, a direct comparative study on their effectiveness in a specific at-risk population, such as anxious children, has been notably absent in the literature. Given the importance of training and intervention for the mental health of anxious children and the necessity of focusing on components like social competence in this population, there is a clear need to determine which approach yields superior results. Therefore, this research was undertaken with the objective of comparing the efficacy of SFCST and ACPT on the social competence of anxious children. The findings aim to provide evidence-based guidance for clinicians and educators in selecting the most impactful intervention for this vulnerable group.

Materials and Methods

Research design and participants

The current clinical trial employed a quasi-experimental design with a pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up structure, along with a control group. This design was selected to compare the efficacy of two distinct therapeutic interventions on the dependent parameter. The statistical population (target population) comprised all anxious children aged 9 to 12 years attending elementary schools in District 5 of Tehran during the 2024-2025 academic year.

The sample size was determined a priori using G*Power 3.1 software for a repeated measures ANOVA, specifically the within-between interaction test family (F tests). Parameters included a medium effect size (f=0.25), α=0.05, statistical power=0.80, number of groups=3 (between-subjects factor), number of measurements=3 (within-subjects factor, df=2), correlation among repeated measures=0.50 (a conservative estimate for short-term follow-up in child interventions), and nonsphericity correction ε=1. This calculation yielded a minimum required sample size of 18 participants per group (total N=54). To accommodate an anticipated attrition rate of up to 10% (common in pediatric psychological trials due to session absences or family withdrawals), recruitment targeted 20 participants per group (total N=60), resulting in the final sample exceeding the powered minimum. A total of 60 female students who met the inclusion criteria were selected using convenience sampling (a purposeful selection followed by simplified random allocation) and subsequently assigned using simple random assignment into three groups (n=20 per group): the SFCST group, the ACPT group, and the control group.

Inclusion criteria for participants were being female and between 9 and 12 years old, receiving a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder from a child and adolescent specialist (psychiatrist or clinical psychologist), not receiving any other concurrent psychological treatment, and obtaining a score indicating below-average social competence on the Social Competence Scale. Exclusion criteria included being absent for more than two intervention sessions, receiving any other therapeutic intervention during the study period, and developing a major psychiatric disorder. No participants were lost to follow-up, resulting in full retention across all groups (0% attrition), which enhanced the study’s statistical power beyond initial estimates. Ethical considerations were strictly observed. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants after they were fully informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, and their right to withdraw at any point without penalty. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured for all data collected.

Instrument

Social Competence Scale-Parent Version (SCS-P)

The SCS-P was employed to measure the dependent parameter. This instrument consists of 12 items designed to assess the child’s social competence, as observed and reported by their parents. The scale utilizes a 5-point Likert-type format ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). The total score ranges from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating a higher level of social competence. The scale comprises two subscales: social/communication skills (items 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12) and emotional regulation skills (items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8). In previous Iranian studies, the SCS-P has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties [22]. For instance, in the research conducted by Gouley et al. [23], the internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for the Persian version was reported as 0.86. In the current study, after translation and back-translation to ensure linguistic equivalence, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated to be 0.88, confirming its high internal consistency and reliability for use with the Iranian student population.

Procedure

Data collection involved administering the SCS-P to all three groups at three time points: pre-test, post-test (immediately after the final session), and at a three-month follow-up. The two experimental groups received their respective intervention protocols over eight 60-minute sessions, administered once per week. The protocols were implemented by a trained clinical psychologist. The control group received no intervention during this period but was offered one of the interventions after the completion of the follow-up phase. The SFCST protocol was adapted from the work of Furman [11] and focused on teaching new skills rather than dwelling on the problems caused by anxiety (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of solution-focused child skills training (SFCST) sessions

The ACPT protocol was designed based on the core processes of ACT, emphasizing psychological flexibility through engaging in play activities (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of acceptance and commitment-based play therapy (ACPT) sessions

Data analysis

The data collected across the three time points (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up) were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) by SPSS 26. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were subsequently utilized to identify specific statistically significant differences between the three groups.

Findings

The study sample comprised 60 female children aged 9-12 years (10.6±1.0) diagnosed with anxiety disorders. All participants were of Persian ethnicity, with no significant baseline differences across groups in age (F=0.42, p=0.664) or socioeconomic status (χ²=3.21, p=0.522), ensuring group comparability.

At baseline, all groups exhibited below-average social competence levels, with comparable means. Post-intervention, both experimental groups showed substantial gains, particularly the SFCST group, while the control group remained stable. These improvements were largely maintained at follow-up, indicating potential durability of effects (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean scores for social/communication skills, emotional regulation skills, and total social competence across groups and time points

Prior to conducting the repeated measures ANOVA, key statistical assumptions were assessed to ensure robustness. Normality of residuals was confirmed via Shapiro-Wilk tests (all p>0.05 across groups and time points). Homogeneity of variances was verified with Levene’s test (p>0.05 for group and time interactions), and sphericity was upheld by Mauchly’s test (χ²<3.12, p>0.05; Greenhouse-Geisser correction applied where ε<0.75, though unnecessary here). These validations supported the parametric approach, minimizing type I error inflation.

The repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects for group (social/communication: F(2, 57)=27.95, p<0.001, η²=0.46; emotional regulation: F(2, 57)=25.89, p<0.001, η²=0.48) and time (social/communication: F(1, 57)=45.42, p<0.001, η²=0.44; emotional regulation: F(1, 57)=78.17, p<0.001, η²=0.58), alongside robust group×time interactions (social/communication: F(2, 114)=10.95, p<0.001, η²=0.28; emotional regulation: F(2, 114)=17.73, p<0.001, η²=0.38; Table 4).

Table 4. Repeated measures ANOVA results for social/communication skills and emotional regulation skills

Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc tests for time effects confirmed significant improvements from pre-test to post-test and from pre-test to follow-up across all parameters. Notably, no significant differences emerged between post-test and follow-up (social/communication, evidencing the stability of gains over three months (Table 5).

Table 5. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons for time effects on social/communication skills and emotional regulation skills

Pairwise group comparisons via Bonferroni correction at post-test highlighted the superiority of both interventions over the control, with SFCST demonstrating the largest effects. For social/communication skills, SFCST outperformed the control (p<0.001) and ACPT (p=0.002), while ACPT also exceeded the control (p<0.001). Similarly, for emotional regulation skills, SFCST surpassed the control (p<0.001) and ACPT (p=0.030), with ACPT being superior to the control (p<0.001; Table 6). These targeted contrasts affirm SFCST’s enhanced efficacy, particularly in fostering adaptive social behaviors among anxious children.

Table 6. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons for group effects on social/communication skills and emotional regulation skills (post-test)

Discussion

This investigation sought to conduct a comparative evaluation of SFCST and ACPT in augmenting social competence among children diagnosed with anxiety disorders. Both interventions engendered statistically significant enhancements in social competence, as measured across the domains of social/communication skills and emotional regulation skills, when benchmarked against the control condition. Of paramount importance, however, is the unequivocal demonstration that SFCST exhibited superior efficacy, manifesting in larger effect sizes relative to ACPT across both subscales and the composite score. Moreover, the post-intervention advancements were robustly maintained at the three-month follow-up, with negligible decay in mean scores, thereby attesting to the longitudinal stability of these therapeutic modalities.

The preeminence of SFCST in this context may be ascribed to its paradigmatically structured, goal-directed, and resource-centric orientation, which resonates profoundly with the developmental exigencies of anxious youth. Children grappling with anxiety frequently exhibit patterns of cognitive evasion and interpersonal reticence, which SFCST adeptly circumvents by pivoting attention toward skill development and the conceptual “absence of the problem” [24]. This methodological shift not only demystifies anxiety-related deficits as surmountable skill gaps but also mitigates the ruminative cycles endemic to such disorders through the provision of discrete, empirically reinforced behavioral scaffolds [25]. Consequently, SFCST facilitates a teleological progression from deficit identification to mastery, fostering adaptive social repertoires with heightened immediacy and transferability. These observations converge seamlessly with extant scholarship affirming SFCST’s significance in psychosocial skill enhancement. For instance, Vatankhah et al. [14] empirically corroborate the modality’s effectiveness in improving life and communication skills among children with intellectual disabilities, underscoring its versatility across neurodevelopmental spectra. Analogously, Soderqvist et al. [26] illuminate the efficacy of solution-focused paradigms in elevating multifaceted social indices among adolescents, thereby extending the generalizability of these benefits to similar age cohorts and contextualizing the present outcomes within a broader evidence base.

Notwithstanding SFCST’s ascendancy, the salutary impact of ACPT in comparison to the control group (evidenced by moderate effect sizes affirms the viability of amalgamating third-wave cognitive-behavioral tenets (specifically, ACT) with the ontogenetically attuned medium of play. At its core, ACPT operationalizes psychological flexibility as the fulcrum for value-congruent behavior amid aversive internal states [27], leveraging playful metaphors to disentangle children from maladaptive cognitive attachments and normalize the accommodation of emotional turbulence [20]. This experiential scaffold thereby mitigates avoidance-driven impediments to social engagement, cultivating a relational resilience consonant with anxiety’s etiological underpinnings. Such affirmations echo contemporary inquiries; notably, Mortazavi et al. [21] indicate ACPT’s enhancement of self-esteem and self-efficacy in elementary-aged cohorts, paralleling the emotional regulation gains observed herein. In tandem, Ahmadvand & Ahmadi Kohanali [28] demonstrate improvements in dyadic parent-child dynamics and attachment security among youth with separation anxiety, thereby reinforcing ACPT’s relational affordances and illuminating its synergistic potential with familial contexts.

The persistence of therapeutic gains over the three-month surveillance interval constitutes a clinically relevant hallmark, suggesting that the latent mechanisms (whether SFCST’s behavioral reinforcement cascades or ACPT’s paradigmatic reorientation toward value-driven action) have been sufficiently consolidated to withstand temporal attrition. This durability aligns with theoretical postulates positing that skill-based interventions promote procedural memory consolidation, whereas flexibility-oriented approaches recalibrate metacognitive schemas, both of which are conducive to prolonged protection against anxiety’s social sequelae [17, 19].

From a practical standpoint, these delineations offer valuable guidance for clinicians navigating pediatric anxiety interventions. SFCST emerges as the preferred strategy for scenarios demanding rapid, measurable behavioral gains, particularly within resource-constrained educational settings. Conversely, ACPT’s experiential ethos may be better suited for younger or verbally reticent children, where play mediates access to abstract constructs. Integratively, hybrid protocols warrant exploration to harness complementary synergies, potentially amplifying outcomes in heterogeneous anxiety presentations.

Notwithstanding these advancements, interpretive caveats are warranted. The use of convenience sampling limited the cohort to female elementary students within a single urban precinct, thereby reducing external validity and precluding inferences about male, rural, or transcultural populations. Furthermore, the parent-proxy assessment via the SCS-P, while psychometrically robust, may introduce reporter bias, potentially underestimating or overestimating child-reported competencies. The quasi-experimental design, lacking full randomization, invites residual confounds from baseline heterogeneity, although this is mitigated by pre-test equivalences. Additionally, the eight-session cadence, while pragmatic, restricts the examination of dose-response dynamics or longer-term trajectories beyond three months.

Prospective inquiries might address these gaps through multisite, randomized controlled trials encompassing diverse demographics and incorporating multimodal assessments (e.g., child self-reports, observational metrics). Longitudinal extensions to one-year intervals would elucidate relapse prevention, while dismantling studies could parse constituent mechanisms (e.g., skill mastery vs. defusion). Ultimately, cost-effectiveness analyses would inform scalable dissemination, embedding these modalities within tiered school-based mental health frameworks to mitigate anxiety’s societal toll.

Conclusion

Both SFCST and ACPT are effective therapeutic interventions for enhancing the social competence of anxious children.

Acknowledgments: The researchers wish to thank all the individuals who participated in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This study obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Sari Branch, Iran (Approval No.: IR.IAU.SARI.REC.1403.428; IRCT Registration: IRCT20250429065530N1), thereby adhering to established ethical protocols.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interests to declare.

Authors' Contribution: Hamidi B (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Ghanadzadegan HA (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Mirzaian B (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%)

Funding/Support: This study did not receive any funding.

Keywords:

Anxiety [MeSH], Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [MeSH], Play Therapy [MeSH], Social Skills [MeSH], Child [MeSH]

References

1. Anderson TL, Valiauga R, Tallo C, Hong CB, Manoranjithan S, Domingo C, et al. Contributing factors to the rise in adolescent anxiety and associated mental health disorders: A narrative review of current literature. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2025;38(1):e70009. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jcap.70009]

2. Michael T, Zetsche U, Margraf J. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Psychiatry. 2007;6(4):136-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.mppsy.2007.01.007]

3. Di Mario S, Rollo E, Gabellini S, Filomeno L. How stress and burnout impact the quality of life amongst healthcare students: An integrative review of the literature. Teach Learn Nurs. 2024;19(4):315-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.teln.2024.04.009]

4. Rapee RM, Creswell C, Kendall PC, Pine DS, Waters AM. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: A summary and overview of the literature. Behav Res Ther. 2023;168:104376. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2023.104376]

5. Li N, Peng J, Sun X, Guo S. Social skill training and children's cognitive concentration in rural China: The mediating effect of social information processing skills. Front Psychol. 2025;16:1526065. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1526065]

6. Schüller I, Demetriou Y. Physical activity interventions promoting social competence at school: A systematic review. Educ Res Rev. 2018;25:39-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.001]

7. Napolitano CM, Sewell MN, Yoon HJ, Soto CJ, Roberts BW. Social, emotional, and behavioral skills: An integrative model of the skills associated with success during adolescence and across the life span. Front Educ. 2021;6:679561. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/feduc.2021.679561]

8. Üstündağ A, Haydaroğlu S, Sayan D, Güngör M. The relationship between social anxiety levels and effective communication skills of adolescents participating in sports. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):15724. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41598-025-00800-1]

9. Yan Y, Zhou X, Zhou J, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Zhou X, et al. The relationship between facial negative physical self and social anxiety in college students: the role of rumination and self-compassion. Front Psychol. 2025;16:1450174. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1450174]

10. Kajastus K, Haravuori H, Kiviruusu O, Marttunen M, Ranta K. Associations of generalized anxiety and social anxiety with perceived difficulties in school in the adolescent general population. J Adolesc. 2024;96(2):291-304. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/jad.12275]

11. Furman B. The solution-focused parent: How to help children conquer challenges by learning skills. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 2023. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9781003435723]

12. Khavari Khorasani R, Ghamari M, Amiri Majd M. Comparing the efficacy of solution-focused kids' skills training and friends program training on anxiety and resilience in children. J Psychol Sci. 2024;23(141):139-60. [Persian] [Link]

13. Hsu KS, Eads R, Lee MY, Wen Z. Solution-focused brief therapy for behavior problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of treatment effectiveness and family involvement. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;120:105620. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105620]

14. Vatankhah M, Hafezi F, Johari Fard R. Comparison effectiveness solution focused kids' skill method and psychodrama on social skill, of educable mentally disabled male students. J Child Health Educ. 2024;5(3):17-27. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32592/jeche.5.3.17]

15. Koukourikos K, Tsaloglidou A, Tzeha L, Iliadis C, Frantzana A, Katsimbeli A, et al. An overview of play therapy. Mater Sociomed. 2021;33(4):293-7. [Link] [DOI:10.5455/msm.2021.33.293-297]

16. Gupta N, Chaudhary R, Gupta M, Ikehara LH, Zubiar F, Madabushi JS. Play therapy as effective options for school-age children with emotional and behavioral problems: A case series. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e40093. [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.40093]

17. Hayes SC, Hofmann SG. "Third-wave" cognitive and behavioral therapies and the emergence of a process-based approach to intervention in psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):363-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/wps.20884]

18. Javid MA, Maredpour A, Malekzadeh M. Comparing the effect of compassionate hypnotherapy and acceptance and commitment therapy on sleep quality in breast cancer patients. J Clin Care Skill. 2023;4(4):219-25. [Link]

19. Tayyebi G, Alwan NH, Hamed AF, Shallal AA, Abdulrazzaq T, Khayayi R. Application of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in children and adolescents psychotherapy: An umbrella review. Iran J Psychiatry. 2024;19(3):337-43. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v19i3.15809]

20. Ghorbanikhah E, Mohammadyfar MA, Moradi S, Delavarpour M. The effectiveness of acceptance-and-commitment-based parenting training on mood and anxiety in children and self-compassion in parents. Pract Clin Psychol. 2023;11(1):81. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.11.1.860.1]

21. Mortazavi SA, Nikrahan GR, Sadoughi M. Comparison of the effectiveness of acceptance-and-commitment play therapy and its integration with training mothers on elementary school children' anxiety, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. J Clin Psychol. 2019;10(3):77-90. [Persian] [Link]

22. Motevally Joybari F, Bakhshipour Joybari B, Abbasi Q. The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral intervention on social competence and school refusal of children with separation anxiety disorder. J TOLOOEBEHDASHT. 2024;23(2):81-99. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.18502/tbj.v23i2.16099]

23. Gouley KK, Brotman LM, Huang KY, Shrout PE. Construct validation of the social competence scale in preschool-age children. Soc Dev. 2008;17(2):380-98. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00430.x]

24. Chen S, Zhang Y, Qu D, He J, Yuan Q, Wang Y, et al. An online solution focused brief therapy for adolescent anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;86:103660. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103660]

25. Behzadi F, Ashori M. Investigating the effectiveness of solution-focused therapy on self-efficacy and social anxiety of adolescents with visual impairment. Appl Psychol. 2024;18(4):170-93. [Persian] [Link]

26. Soderqvist F, Uvhagen L, Gustafsson J, Franklin C. The solution-focused intervention for mental health (SIM): Description and feasibility testing of a positive psychology intervention in Swedish adolescents. SSM Ment Health. 2025;8:100493. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ssmmh.2025.100493]

27. Swain J, Hancock K, Dixon A, Koo S, Bowman J. Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxious children and adolescents: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:140. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1745-6215-14-140]

28. Ahmadvand S, Ahmadi Kohanali H. The study of effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on reduction separation anxiety disorder symptoms in children. Clin Psychol Achiev. 2017;3(2):173-92. [Persian] [Link]