Volume 6, Issue 4 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(4): 203-209 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.IUMS.REC.1397.057

History

Received: 2025/08/7 | Accepted: 2025/09/25 | Published: 2025/10/18

Received: 2025/08/7 | Accepted: 2025/09/25 | Published: 2025/10/18

How to cite this article

Sabeti F, Tofigh S. Parental Satisfaction in the Pediatric Intensive Care Units. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (4) :203-209

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-443-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-443-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (5 Views)

Introduction

In the field of healthcare, patient satisfaction has become one of the most important and challenging competitive elements in healthcare centers concerning the quality of healthcare services evaluation index [1, 2]. Patient satisfaction is a multidimensional, complex, and context-dependent concept [3] that relates to the patient’s experiences before, during, and after care, as well as their expectations [4]. In other words, the concept of satisfaction in healthcare provision refers to the feelings or attitudes of clients towards the services provided. Satisfaction is the difference between the patient’s expectations of the quality of healthcare and the quality of care received [5]. Parents are among the most important members of the multidisciplinary health team. Therefore, measuring parents’ satisfaction with healthcare can serve as a valuable surrogate parameter for assessing the quality of care [6].

On the other hand, measuring the quality of health services helps health system managers effectively regulate monitoring mechanisms and implement improvement programs. In this regard, service providers can facilitate motivation, design, and evaluate effective measures to improve the quality of care by conducting periodic surveys on parental satisfaction and monitoring the consequences of changes resulting from hospital improvement programs [7]. According to Salmani et al., satisfaction with nursing care is a cognitive-emotional-behavioral process, and all components of this process should be emphasized by nurses, managers, and nursing officials to promote parental satisfaction with hospitalized children [8]. Thus, determining parental satisfaction with healthcare plays a decisive role in assessing the quality of nursing services provided to children. This assessment not only makes care and treatment methods transparent but also identifies the level of support from nurses and family satisfaction as key indicators of service quality, especially in nursing care.

Parents benefit from professional nursing services during their child’s hospitalization, which significantly reduces their stress and anxiety levels. Reducing psychological stress leads to increased trust in nurses and satisfaction with medical services, ultimately having a favorable effect on the child’s treatment and care process [9]. Additionally, parents’ opinions can play a key role in improving the human and communicative aspects of care and provide a basis for designing training courses to enhance the knowledge and communication skills of medical staff [7].

The hospitalization of a child is known to be a very stressful experience for parents, as they face a lack of knowledge about treatment processes, medical diagnoses, and environmental and daily changes [1]. The pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) is undoubtedly a stressful environment for parents [10]. When a child is admitted to the intensive care unit, the critical health status of the child exacerbates feelings such as anxiety and helplessness in parents [11]. This situation further highlights the importance of addressing parental satisfaction in the PICU. Based on the searches conducted, the researcher did not find a similar study on parental satisfaction in the PICU in Iran, and studies conducted abroad also yielded different results in various dimensions of satisfaction. Abuqamar et al. showed that overall satisfaction in the PICU was satisfactory; however, in the environmental component, more than half of the parents were dissatisfied with the volume of noise in the PICU. In the care component, 73% stated that nurses do not spend enough time at the child’s bedside, and 70.7% were dissatisfied with the reception upon arrival. Ninety percent of parents believed that nurses ignored the child’s needs by not listening to the parents. In the communication component, they were dissatisfied with the manner in which parents were informed about their child [12].

Additionally, Ebrahim et al. showed that although overall parental satisfaction with children admitted to the PICU is high, parental satisfaction is lower in cases where more invasive treatments are performed on the child [13]. Terp et al. report the overall satisfaction of parents with care in the PICU as high; however, the results of the study emphasize the need to improve family-centered care, especially in the areas of information sharing and parental participation in decision-making about their child’s care [14]. Sahota et al. also found that overall, most parents are satisfied with the services provided in the PICU, and, except for the level of parental anxiety—which has a significant negative relationship with their satisfaction—other factors, such as the severity of the child’s illness, financial status, or level of parental education do not have a significant effect on their satisfaction [10].

Given the importance of parental satisfaction as a key indicator for assessing the quality of care in healthcare systems [6, 7, 9], as well as the significance of the PICU in providing quality care to critically ill children [15], and the psychological effects that a child’s hospitalization in the intensive care unit has on parents [16]—all of which affect parental satisfaction—this study aimed to determine parental satisfaction based on the components of environment, care, and communication in the PICU, especially since, based on the researcher’s review of the literature, no relevant study has been conducted in PICUs in Iran.

Materials and Methods

Design and sample

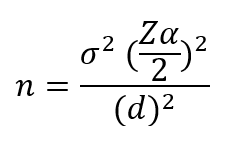

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the PICUs of the educational and medical centers affiliated with Iran University of Medical Sciences. The sample consisted of 120 parents of children hospitalized in the PICU who, based on the inclusion criteria, had been hospitalized for at least 48 hours and had the desire and informed consent to participate in the study. The required sample size was estimated to be 120 individuals based on a type I error of 5% (Z(α/2)=1.96) and a design effect of 18%, using the formula below:

Instrument

The data collection tools included a demographic-clinical information questionnaire (child’s age, gender, birth order, diagnosis, length of hospitalization, hospitalization history, severity of illness, and parents’ age, gender, level of education, occupation, number of children, place of residence, and type of insurance) and a Parent Satisfaction Survey questionnaire. This tool was designed by McPherson et al. in 2000 to assess parental satisfaction in PICUs [17]. The questionnaire has 24 items across three domains: environment (4 items), care (10 items), and communication (10 items), using a five-point Likert scale, with a score of 1 indicating complete disagreement and a score of 5 indicating complete agreement. The highest and lowest overall scores are 120 and 24, respectively, while in each of the domains—environment, care, and communication—the highest scores are 20, 50, and 50, and the lowest scores are 4, 10, and 10, respectively [12]. McPherson et al. determined its reliability by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which was found to be .83, indicating desirable reliability [17]. In the study by Abuqamar et al., Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported to be 0.87, which is also acceptable. Furthermore, the internal consistency of this questionnaire was determined to be α=0.64 for the environment domain, α=0.74 for care, and α=0.89 for communication [12], which is considered acceptable for the environment domain due to the small number of items, according to Hinton et al. [18].

The researcher, after translating and retranslating the questionnaire with the help of a person fluent in English, provided it to the members of the proposal review team. After reviewing the opinions of the review team, the necessary changes were made to the questionnaire. The reliability of the instrument was assessed by examining internal consistency, which was determined by having 20 parents of children hospitalized in the intensive care unit complete the questionnaire and calculating Cronbach’s alpha at the desired level. Thus, the Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was calculated to be 0.91 for the whole scale and 0.62, 0.79, and 0.85 for the environment, care, and communication domains, respectively, which is considered acceptable.

Data collection

After receiving the ethics code from the Research Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences and submitting a letter of introduction to the educational and medical centers (Hazrat Rasoul Akram Hospital and Hazrat Ali Asghar Hospital), the researcher conducted sampling using a proportional sampling method based on the number of patients in the centers and considering the study’s inclusion criteria from June 22 to October 07, 2019. After introducing himself to the parents, the researcher explained the nature and objectives of the study. If the parents were willing to participate in the study, they completed an informed consent form. The parents were assured that participation in the study was completely voluntary and did not require their names, that the results would be kept confidential and published in general terms, and that participation or non-participation in the study would not affect the care of their hospitalized child. Thus, at the time of discharge, when the parents were ready to complete the questionnaire, the researcher provided them with the questionnaires and was available to answer any questions they had. In the case of parents who were illiterate, the researcher read the questionnaire options one by one and slowly marked the answers. The time required to complete the questionnaires was between 5 and 10 minutes.

Data analysis

SPSS 22 software was used to analyze the data using the independent t-test, one-way analysis of variance, and Pearson correlation coefficient. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Findings

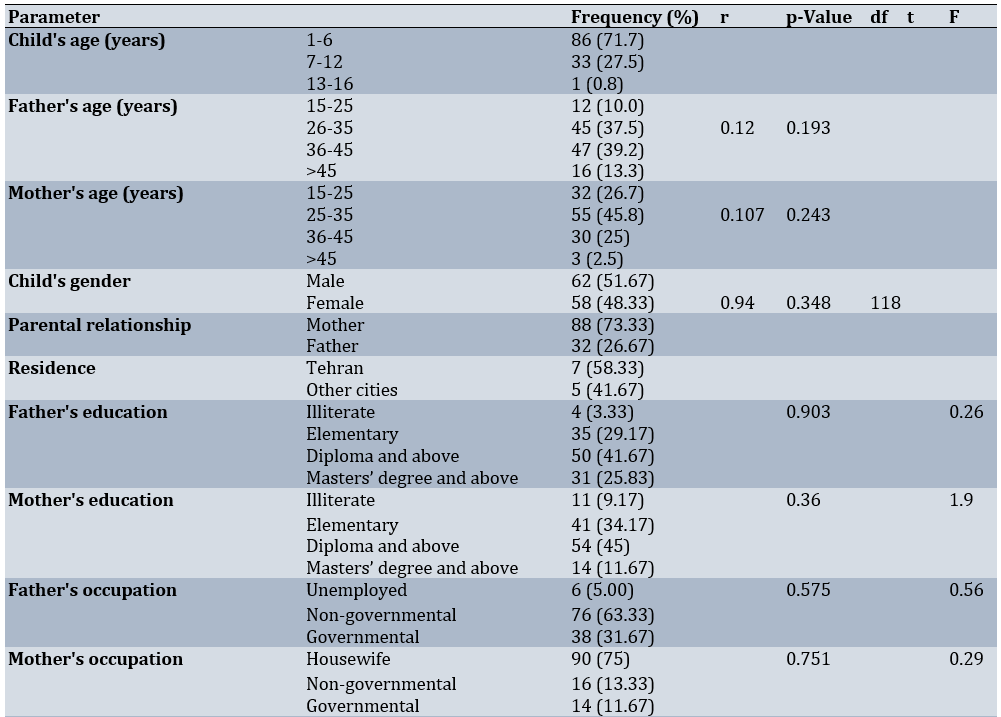

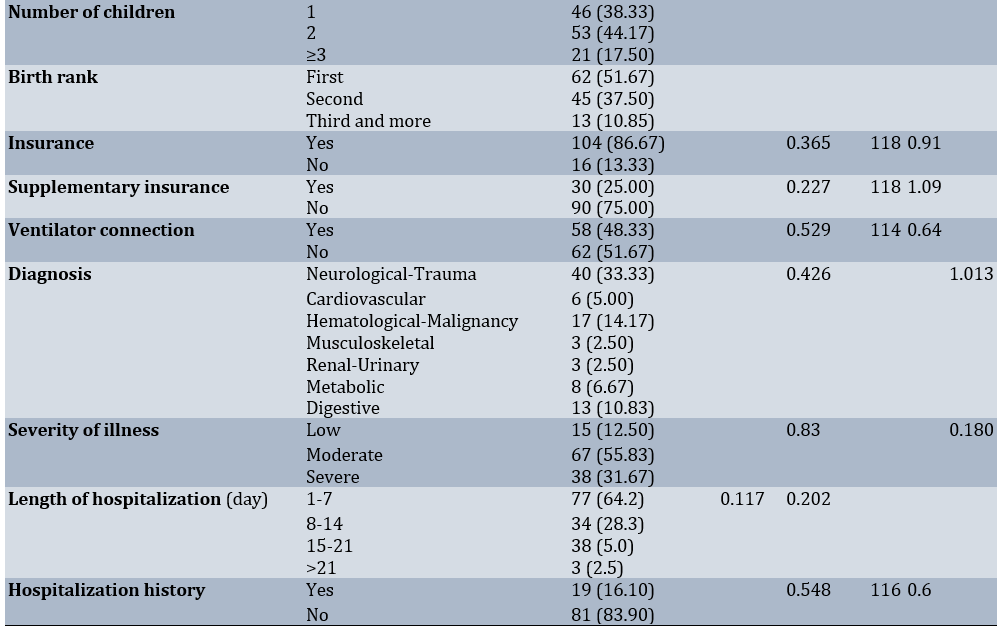

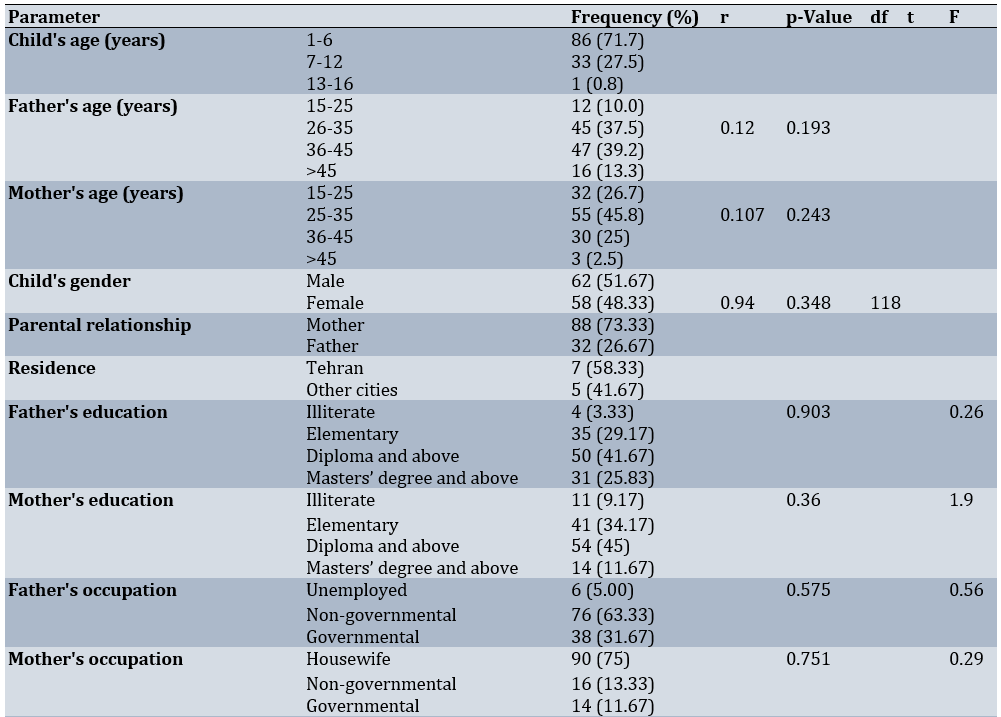

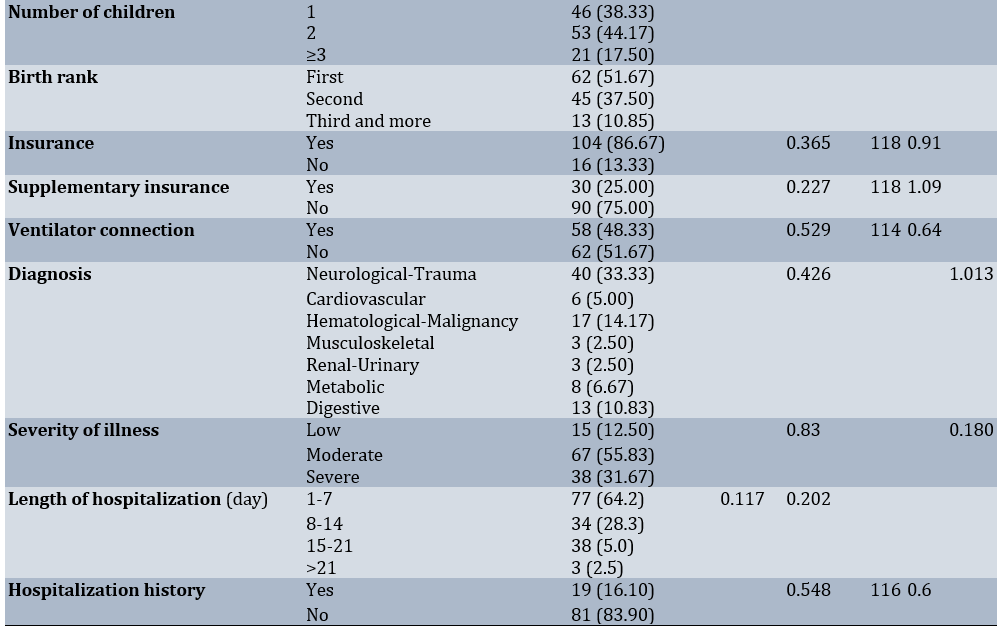

The average age of fathers was 35.77±8.10 years, mothers was 30.73±7.01 years, and children was 5.24±22.09 years. Additionally, 51.67% of the children were boys and 48.33% were girls, while 73.33% of mothers and 26.67% of fathers participated in the study. The majority of parents resided in Tehran (58.33%). Most fathers (41.67%) and mothers (45.00%) had a diploma or a higher education level. Furthermore, 63.33% of fathers were self-employed, and 75.00% of mothers were housewives. Most families (44.17%) had two children. In most cases (51.67%), the child was the firstborn in the family. Most children (86.67%) had health insurance, while 75.00% did not have supplementary insurance, and 51.67% of the children were not connected to a mechanical ventilator. The cause of hospitalization (33.33%) was reported as neurological/trauma in most cases. The average length of hospitalization for children was 8.07 days. Most of the children (83.90%) had no history of hospitalization in the intensive care unit (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects and their relationship with job satisfaction

The average satisfaction of parents, in general, was 85.28±7.49. The average satisfaction in the environment domain was 14.74±2.08, in care was 38.66±2.42, and in communication was 33.23±4.03. The results of the average satisfaction of parents, separated by each item in the environment area, showed that about 90% of parents were satisfied with the cleanliness and tidiness of their child’s bed and the ward. Additionally, more than half of the parents were satisfied with the silence of the ward, and only 13% were dissatisfied with the crowding of the ward. In the care domain, 90% of the parents were satisfied with the care their child received in the ward, and in more than 70% of cases, they would recommend this hospital to others. Furthermore, 72% of the parents reported that the nurses were good and kind caregivers, and this item was reported for the doctors in 87% of cases. In more than 70% of cases, parents reported that “nurses were slow to respond to their child’s needs” and “felt that care providers did not spend enough time at their child’s bedside.” In terms of communication, doctors answered parents’ questions in more than 75% of cases, and 70% of healthcare providers gave parents good information about their child. In half of the cases, nurses did not really listen to parents’ concerns about their child’s needs, and in less than half of the cases, parents received the necessary preparation and support for the child’s admission to the ward.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine parental satisfaction and its relationship with demographic and clinical characteristics in the PICU. The mean parental satisfaction score, both overall and in each of the environment, care, and communication domains, was higher than the median score and deemed satisfactory. These results are consistent with those of Ebrahim et al. [13], Abuqamar et al. [12], Cintra et al. [16], Sahota et al. [10], and Terp et al. [14]. Although overall parental satisfaction in the PICU was high in our study and the studies mentioned, examining the satisfaction domains in detail reveals points worth considering and addressing. Regarding the environment, about 90% of parents were satisfied with the cleanliness and tidiness of their child’s bed. Additionally, more than half of the parents were satisfied with the silence of the ward, and only 13% were dissatisfied with the noise in the ward. However, according to Abuqamar et al., in the environmental component, while similar to our study, the majority of parents are completely satisfied with the cleanliness of the ward, more than half were dissatisfied with the volume of noise in the PICU [12]. According to the researcher’s studies in the PICU of the hospitals examined, head and shift nurses carefully monitor the cleanliness of the ward, which has been associated with parents’ satisfaction. On the other hand, despite the noise and crowding in the ward, especially due to the presence of medical students during rounds, the cleanliness of the environment was likely more important to parents than the crowding, or perhaps the noise was more pronounced during times when parents were not in the ward and thus did not notice the crowding.

Regarding care, although most parents were satisfied with the care provided by the medical staff, including doctors and nurses, and considered them to be good and kind caregivers, there are noteworthy concerns. For example, 90% of parents were satisfied with the care their child received in the ward overall, and in more than 70% of cases, they would recommend this hospital to others. However, the fact that more than 70% of parents reported items, such as “Nurses respond slowly to my child’s needs” and “I feel that the care providers do not spend enough time at my child’s bedside” is very significant. These results align closely with those of Abuqamar et al., showing that 93.5% of parents believe that nurses respond slowly to their child’s needs, and 73% of parents state that care providers do not spend enough time at the child’s bedside [12]. These findings may be attributed to the high workload of nurses and the low nurse-to-patient ratio, as well as the time nurses spend recording written reports, which limits their availability at the child’s bedside to respond quickly when needed. On the other hand, it is also possible that nurses sometimes do not fully understand the needs of children and may not take their non-emergency needs seriously.

According to Abuqamar et al., PICU nurses are often too busy to properly identify the needs of children [12]. It is very important for parents that care providers, especially nurses, are available to them and respond to their child’s needs as quickly as possible. Parents need to communicate more with their child’s doctor and nurse and be well informed about the decisions and treatment plan. The points mentioned above are part of the principles of professional medical ethics. In other words, care is a moral virtue and a key element in the nursing profession, and the implementation of ethical nursing care is one of the most important factors in the satisfaction of parents of hospitalized children. Providing nursing care by nurses who adhere to the ethical principles of nursing can improve the quality of care [19].

Regarding communication, the highest mean score was associated with the item “The ward doctors answer my questions completely.” In other words, the doctors answered the parents’ questions in more than 75% of cases. On the other hand, in half of the cases, nurses did not really listen to the parents’ concerns about their child’s needs, and in less than half of the cases, the parents received the necessary preparations for the child’s admission to the ward. The resident physician’s room was located next to the PICU, and every day at the appointed time, parents had the opportunity to meet with their child’s doctor and discuss the illness, the course of treatment, or any other issues. The relevant doctor was also closely responsible for all parents. These factors contributed to parents’ satisfaction with their doctors. Abuqamar et al. showed that more than half of the parents are dissatisfied with the way doctors inform them about the results of tests and other procedures regarding their child [12], which is inconsistent with our results, which indicated that about 70% of parents were satisfied with the way the care team informed them about the results of their child’s condition and other treatment procedures.

On the other hand, in line with our study, the same research showed that 98% of parents believe that nurses ignore the child’s needs by not listening to them, and 70.7% of parents are dissatisfied with the reception upon arrival [12]. It should be noted that active listening is a vital communication skill and a sure way to ensure effective communication [20]. Active listening is key to effective communication [21], and based on our results, nurses should place greater emphasis on this skill. Admission to critical care units, such as the PICU, has a greater emotional impact on children and their parents than admission to a general pediatric inpatient unit, which complicates the process of supporting and educating families at the time of admission, discharge, or transfer, and requires arrangements to ensure family safety and security [16, 22]. In the study by Ebrahim et al., the level of satisfaction of parents with the communication of their child’s caregivers is 87.6%, and the level of satisfaction with participation in decision-making is 70.2% [13]. Effective communication between children’s nurses and their parents is recognized as a key tool in providing quality health care [20]. According to Cintra et al., one of the important factors in increasing parental satisfaction is effective communication between parents and the multidisciplinary health team [16]. In this regard, communication is the foundation of the care process in pediatric nursing [23], and the nurse’s communication skills are a key component of family-centered care [24]. Therefore, establishing effective and efficient communication between the nurse, the hospitalized child, and their family is essential [25]. Additionally, considering the stressful conditions of the PICU, psychological support for parents is emphasized by the medical staff, especially nurses, during the child’s hospitalization in the unit [26]. To achieve this goal, establishing appropriate therapeutic communication and building trust as the foundation for developing nurse-patient relationships is essential [27]. In this context, to improve parental satisfaction, there is still a need for training healthcare providers in communicating with parents, and extensive studies are necessary to identify measures to enhance parental satisfaction in PICUs [10].

No significant relationship was found between parental satisfaction and demographic characteristics such as age, gender, education level, occupation, and place of residence. Additionally, no significant statistical relationship was identified between clinical parameters, including history and duration of hospitalization, insurance coverage, cause of hospitalization, and severity of disease. This may be due to the small sample size in the study, which is one of the limitations of our research. These findings are consistent with the results of Cintra et al., who report no statistically significant relationship between parental satisfaction and length of stay, type of illness, and severity of illness [16]. In the study by Abuqamar et al., a significant relationship is reported between parental satisfaction and the number of hospitalizations, insurance services, and severity of the child’s illness [12]. In the study by Hosseinian et al., there is also a significant relationship between parental satisfaction and the type of child’s illness, which suggests that in cases of acute illness, the rapid care and treatment provided by the medical staff resulted in higher parental satisfaction compared to chronic illness conditions [28].

The limitations of the present study include the small sample size, which is due to the limited number of PICU beds and the extended hospitalization period for some patients. Additionally, since parents cannot be fully present with their children in our PICUs, some parents’ opinions may differ slightly from reality.

Professional care provided by the medical staff, including nurses and doctors, effective communication between doctors and parents, responsiveness, and accurate information given by care providers regarding the child’s condition and treatment process, as well as the cleanliness and tidiness of the environment, were important factors influencing parental satisfaction. Although satisfaction with both nurses and doctors was reported to be high in the care domain, doctors received higher scores.

In terms of communication, understanding children’s needs and responding promptly, providing more support and communication with the child and family, and delivering accurate information about the child’s condition by nurses are priorities for improving the quality of care and enhancing parental satisfaction. To this end, while reinforcing the positive aspects mentioned, it is also necessary to improve communication between nurses and the child and family. It is suggested that improvement measures be implemented to increase knowledge, change attitudes, and enhance nurses’ performance in the area of professional communication skills with children and families, considering generational differences among nurses and utilizing modern educational methods.

Conclusion

Professional care, effective physician-parent communication, accurate information about the child’s condition and treatment, and a clean environment are key factors in parental satisfaction.

Acknowledgements: This article is the result of Mr. Shafaq Tofghi’s doctoral thesis in the field of pediatric nursing. The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Research Assistant at Iran University of Medical Sciences for approving and financially supporting the thesis. The researchers would especially like to thank the parents who participated in the study, as well as the managers, nurses, and doctors of the pediatric intensive care unit at the educational and medical centers involved.

Ethical Permissions: Ethics code IR.IUMS.REC.1397.057 was issued by the Research Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences to conduct this research.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Sabeti F (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (60%); Towfiq Sh (Second Author), Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%)

Funding/Support: The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Research Assistant at Iran University of Medical Sciences for approving and financially supporting the research.

In the field of healthcare, patient satisfaction has become one of the most important and challenging competitive elements in healthcare centers concerning the quality of healthcare services evaluation index [1, 2]. Patient satisfaction is a multidimensional, complex, and context-dependent concept [3] that relates to the patient’s experiences before, during, and after care, as well as their expectations [4]. In other words, the concept of satisfaction in healthcare provision refers to the feelings or attitudes of clients towards the services provided. Satisfaction is the difference between the patient’s expectations of the quality of healthcare and the quality of care received [5]. Parents are among the most important members of the multidisciplinary health team. Therefore, measuring parents’ satisfaction with healthcare can serve as a valuable surrogate parameter for assessing the quality of care [6].

On the other hand, measuring the quality of health services helps health system managers effectively regulate monitoring mechanisms and implement improvement programs. In this regard, service providers can facilitate motivation, design, and evaluate effective measures to improve the quality of care by conducting periodic surveys on parental satisfaction and monitoring the consequences of changes resulting from hospital improvement programs [7]. According to Salmani et al., satisfaction with nursing care is a cognitive-emotional-behavioral process, and all components of this process should be emphasized by nurses, managers, and nursing officials to promote parental satisfaction with hospitalized children [8]. Thus, determining parental satisfaction with healthcare plays a decisive role in assessing the quality of nursing services provided to children. This assessment not only makes care and treatment methods transparent but also identifies the level of support from nurses and family satisfaction as key indicators of service quality, especially in nursing care.

Parents benefit from professional nursing services during their child’s hospitalization, which significantly reduces their stress and anxiety levels. Reducing psychological stress leads to increased trust in nurses and satisfaction with medical services, ultimately having a favorable effect on the child’s treatment and care process [9]. Additionally, parents’ opinions can play a key role in improving the human and communicative aspects of care and provide a basis for designing training courses to enhance the knowledge and communication skills of medical staff [7].

The hospitalization of a child is known to be a very stressful experience for parents, as they face a lack of knowledge about treatment processes, medical diagnoses, and environmental and daily changes [1]. The pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) is undoubtedly a stressful environment for parents [10]. When a child is admitted to the intensive care unit, the critical health status of the child exacerbates feelings such as anxiety and helplessness in parents [11]. This situation further highlights the importance of addressing parental satisfaction in the PICU. Based on the searches conducted, the researcher did not find a similar study on parental satisfaction in the PICU in Iran, and studies conducted abroad also yielded different results in various dimensions of satisfaction. Abuqamar et al. showed that overall satisfaction in the PICU was satisfactory; however, in the environmental component, more than half of the parents were dissatisfied with the volume of noise in the PICU. In the care component, 73% stated that nurses do not spend enough time at the child’s bedside, and 70.7% were dissatisfied with the reception upon arrival. Ninety percent of parents believed that nurses ignored the child’s needs by not listening to the parents. In the communication component, they were dissatisfied with the manner in which parents were informed about their child [12].

Additionally, Ebrahim et al. showed that although overall parental satisfaction with children admitted to the PICU is high, parental satisfaction is lower in cases where more invasive treatments are performed on the child [13]. Terp et al. report the overall satisfaction of parents with care in the PICU as high; however, the results of the study emphasize the need to improve family-centered care, especially in the areas of information sharing and parental participation in decision-making about their child’s care [14]. Sahota et al. also found that overall, most parents are satisfied with the services provided in the PICU, and, except for the level of parental anxiety—which has a significant negative relationship with their satisfaction—other factors, such as the severity of the child’s illness, financial status, or level of parental education do not have a significant effect on their satisfaction [10].

Given the importance of parental satisfaction as a key indicator for assessing the quality of care in healthcare systems [6, 7, 9], as well as the significance of the PICU in providing quality care to critically ill children [15], and the psychological effects that a child’s hospitalization in the intensive care unit has on parents [16]—all of which affect parental satisfaction—this study aimed to determine parental satisfaction based on the components of environment, care, and communication in the PICU, especially since, based on the researcher’s review of the literature, no relevant study has been conducted in PICUs in Iran.

Materials and Methods

Design and sample

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the PICUs of the educational and medical centers affiliated with Iran University of Medical Sciences. The sample consisted of 120 parents of children hospitalized in the PICU who, based on the inclusion criteria, had been hospitalized for at least 48 hours and had the desire and informed consent to participate in the study. The required sample size was estimated to be 120 individuals based on a type I error of 5% (Z(α/2)=1.96) and a design effect of 18%, using the formula below:

Instrument

The data collection tools included a demographic-clinical information questionnaire (child’s age, gender, birth order, diagnosis, length of hospitalization, hospitalization history, severity of illness, and parents’ age, gender, level of education, occupation, number of children, place of residence, and type of insurance) and a Parent Satisfaction Survey questionnaire. This tool was designed by McPherson et al. in 2000 to assess parental satisfaction in PICUs [17]. The questionnaire has 24 items across three domains: environment (4 items), care (10 items), and communication (10 items), using a five-point Likert scale, with a score of 1 indicating complete disagreement and a score of 5 indicating complete agreement. The highest and lowest overall scores are 120 and 24, respectively, while in each of the domains—environment, care, and communication—the highest scores are 20, 50, and 50, and the lowest scores are 4, 10, and 10, respectively [12]. McPherson et al. determined its reliability by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which was found to be .83, indicating desirable reliability [17]. In the study by Abuqamar et al., Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported to be 0.87, which is also acceptable. Furthermore, the internal consistency of this questionnaire was determined to be α=0.64 for the environment domain, α=0.74 for care, and α=0.89 for communication [12], which is considered acceptable for the environment domain due to the small number of items, according to Hinton et al. [18].

The researcher, after translating and retranslating the questionnaire with the help of a person fluent in English, provided it to the members of the proposal review team. After reviewing the opinions of the review team, the necessary changes were made to the questionnaire. The reliability of the instrument was assessed by examining internal consistency, which was determined by having 20 parents of children hospitalized in the intensive care unit complete the questionnaire and calculating Cronbach’s alpha at the desired level. Thus, the Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was calculated to be 0.91 for the whole scale and 0.62, 0.79, and 0.85 for the environment, care, and communication domains, respectively, which is considered acceptable.

Data collection

After receiving the ethics code from the Research Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences and submitting a letter of introduction to the educational and medical centers (Hazrat Rasoul Akram Hospital and Hazrat Ali Asghar Hospital), the researcher conducted sampling using a proportional sampling method based on the number of patients in the centers and considering the study’s inclusion criteria from June 22 to October 07, 2019. After introducing himself to the parents, the researcher explained the nature and objectives of the study. If the parents were willing to participate in the study, they completed an informed consent form. The parents were assured that participation in the study was completely voluntary and did not require their names, that the results would be kept confidential and published in general terms, and that participation or non-participation in the study would not affect the care of their hospitalized child. Thus, at the time of discharge, when the parents were ready to complete the questionnaire, the researcher provided them with the questionnaires and was available to answer any questions they had. In the case of parents who were illiterate, the researcher read the questionnaire options one by one and slowly marked the answers. The time required to complete the questionnaires was between 5 and 10 minutes.

Data analysis

SPSS 22 software was used to analyze the data using the independent t-test, one-way analysis of variance, and Pearson correlation coefficient. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Findings

The average age of fathers was 35.77±8.10 years, mothers was 30.73±7.01 years, and children was 5.24±22.09 years. Additionally, 51.67% of the children were boys and 48.33% were girls, while 73.33% of mothers and 26.67% of fathers participated in the study. The majority of parents resided in Tehran (58.33%). Most fathers (41.67%) and mothers (45.00%) had a diploma or a higher education level. Furthermore, 63.33% of fathers were self-employed, and 75.00% of mothers were housewives. Most families (44.17%) had two children. In most cases (51.67%), the child was the firstborn in the family. Most children (86.67%) had health insurance, while 75.00% did not have supplementary insurance, and 51.67% of the children were not connected to a mechanical ventilator. The cause of hospitalization (33.33%) was reported as neurological/trauma in most cases. The average length of hospitalization for children was 8.07 days. Most of the children (83.90%) had no history of hospitalization in the intensive care unit (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects and their relationship with job satisfaction

The average satisfaction of parents, in general, was 85.28±7.49. The average satisfaction in the environment domain was 14.74±2.08, in care was 38.66±2.42, and in communication was 33.23±4.03. The results of the average satisfaction of parents, separated by each item in the environment area, showed that about 90% of parents were satisfied with the cleanliness and tidiness of their child’s bed and the ward. Additionally, more than half of the parents were satisfied with the silence of the ward, and only 13% were dissatisfied with the crowding of the ward. In the care domain, 90% of the parents were satisfied with the care their child received in the ward, and in more than 70% of cases, they would recommend this hospital to others. Furthermore, 72% of the parents reported that the nurses were good and kind caregivers, and this item was reported for the doctors in 87% of cases. In more than 70% of cases, parents reported that “nurses were slow to respond to their child’s needs” and “felt that care providers did not spend enough time at their child’s bedside.” In terms of communication, doctors answered parents’ questions in more than 75% of cases, and 70% of healthcare providers gave parents good information about their child. In half of the cases, nurses did not really listen to parents’ concerns about their child’s needs, and in less than half of the cases, parents received the necessary preparation and support for the child’s admission to the ward.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine parental satisfaction and its relationship with demographic and clinical characteristics in the PICU. The mean parental satisfaction score, both overall and in each of the environment, care, and communication domains, was higher than the median score and deemed satisfactory. These results are consistent with those of Ebrahim et al. [13], Abuqamar et al. [12], Cintra et al. [16], Sahota et al. [10], and Terp et al. [14]. Although overall parental satisfaction in the PICU was high in our study and the studies mentioned, examining the satisfaction domains in detail reveals points worth considering and addressing. Regarding the environment, about 90% of parents were satisfied with the cleanliness and tidiness of their child’s bed. Additionally, more than half of the parents were satisfied with the silence of the ward, and only 13% were dissatisfied with the noise in the ward. However, according to Abuqamar et al., in the environmental component, while similar to our study, the majority of parents are completely satisfied with the cleanliness of the ward, more than half were dissatisfied with the volume of noise in the PICU [12]. According to the researcher’s studies in the PICU of the hospitals examined, head and shift nurses carefully monitor the cleanliness of the ward, which has been associated with parents’ satisfaction. On the other hand, despite the noise and crowding in the ward, especially due to the presence of medical students during rounds, the cleanliness of the environment was likely more important to parents than the crowding, or perhaps the noise was more pronounced during times when parents were not in the ward and thus did not notice the crowding.

Regarding care, although most parents were satisfied with the care provided by the medical staff, including doctors and nurses, and considered them to be good and kind caregivers, there are noteworthy concerns. For example, 90% of parents were satisfied with the care their child received in the ward overall, and in more than 70% of cases, they would recommend this hospital to others. However, the fact that more than 70% of parents reported items, such as “Nurses respond slowly to my child’s needs” and “I feel that the care providers do not spend enough time at my child’s bedside” is very significant. These results align closely with those of Abuqamar et al., showing that 93.5% of parents believe that nurses respond slowly to their child’s needs, and 73% of parents state that care providers do not spend enough time at the child’s bedside [12]. These findings may be attributed to the high workload of nurses and the low nurse-to-patient ratio, as well as the time nurses spend recording written reports, which limits their availability at the child’s bedside to respond quickly when needed. On the other hand, it is also possible that nurses sometimes do not fully understand the needs of children and may not take their non-emergency needs seriously.

According to Abuqamar et al., PICU nurses are often too busy to properly identify the needs of children [12]. It is very important for parents that care providers, especially nurses, are available to them and respond to their child’s needs as quickly as possible. Parents need to communicate more with their child’s doctor and nurse and be well informed about the decisions and treatment plan. The points mentioned above are part of the principles of professional medical ethics. In other words, care is a moral virtue and a key element in the nursing profession, and the implementation of ethical nursing care is one of the most important factors in the satisfaction of parents of hospitalized children. Providing nursing care by nurses who adhere to the ethical principles of nursing can improve the quality of care [19].

Regarding communication, the highest mean score was associated with the item “The ward doctors answer my questions completely.” In other words, the doctors answered the parents’ questions in more than 75% of cases. On the other hand, in half of the cases, nurses did not really listen to the parents’ concerns about their child’s needs, and in less than half of the cases, the parents received the necessary preparations for the child’s admission to the ward. The resident physician’s room was located next to the PICU, and every day at the appointed time, parents had the opportunity to meet with their child’s doctor and discuss the illness, the course of treatment, or any other issues. The relevant doctor was also closely responsible for all parents. These factors contributed to parents’ satisfaction with their doctors. Abuqamar et al. showed that more than half of the parents are dissatisfied with the way doctors inform them about the results of tests and other procedures regarding their child [12], which is inconsistent with our results, which indicated that about 70% of parents were satisfied with the way the care team informed them about the results of their child’s condition and other treatment procedures.

On the other hand, in line with our study, the same research showed that 98% of parents believe that nurses ignore the child’s needs by not listening to them, and 70.7% of parents are dissatisfied with the reception upon arrival [12]. It should be noted that active listening is a vital communication skill and a sure way to ensure effective communication [20]. Active listening is key to effective communication [21], and based on our results, nurses should place greater emphasis on this skill. Admission to critical care units, such as the PICU, has a greater emotional impact on children and their parents than admission to a general pediatric inpatient unit, which complicates the process of supporting and educating families at the time of admission, discharge, or transfer, and requires arrangements to ensure family safety and security [16, 22]. In the study by Ebrahim et al., the level of satisfaction of parents with the communication of their child’s caregivers is 87.6%, and the level of satisfaction with participation in decision-making is 70.2% [13]. Effective communication between children’s nurses and their parents is recognized as a key tool in providing quality health care [20]. According to Cintra et al., one of the important factors in increasing parental satisfaction is effective communication between parents and the multidisciplinary health team [16]. In this regard, communication is the foundation of the care process in pediatric nursing [23], and the nurse’s communication skills are a key component of family-centered care [24]. Therefore, establishing effective and efficient communication between the nurse, the hospitalized child, and their family is essential [25]. Additionally, considering the stressful conditions of the PICU, psychological support for parents is emphasized by the medical staff, especially nurses, during the child’s hospitalization in the unit [26]. To achieve this goal, establishing appropriate therapeutic communication and building trust as the foundation for developing nurse-patient relationships is essential [27]. In this context, to improve parental satisfaction, there is still a need for training healthcare providers in communicating with parents, and extensive studies are necessary to identify measures to enhance parental satisfaction in PICUs [10].

No significant relationship was found between parental satisfaction and demographic characteristics such as age, gender, education level, occupation, and place of residence. Additionally, no significant statistical relationship was identified between clinical parameters, including history and duration of hospitalization, insurance coverage, cause of hospitalization, and severity of disease. This may be due to the small sample size in the study, which is one of the limitations of our research. These findings are consistent with the results of Cintra et al., who report no statistically significant relationship between parental satisfaction and length of stay, type of illness, and severity of illness [16]. In the study by Abuqamar et al., a significant relationship is reported between parental satisfaction and the number of hospitalizations, insurance services, and severity of the child’s illness [12]. In the study by Hosseinian et al., there is also a significant relationship between parental satisfaction and the type of child’s illness, which suggests that in cases of acute illness, the rapid care and treatment provided by the medical staff resulted in higher parental satisfaction compared to chronic illness conditions [28].

The limitations of the present study include the small sample size, which is due to the limited number of PICU beds and the extended hospitalization period for some patients. Additionally, since parents cannot be fully present with their children in our PICUs, some parents’ opinions may differ slightly from reality.

Professional care provided by the medical staff, including nurses and doctors, effective communication between doctors and parents, responsiveness, and accurate information given by care providers regarding the child’s condition and treatment process, as well as the cleanliness and tidiness of the environment, were important factors influencing parental satisfaction. Although satisfaction with both nurses and doctors was reported to be high in the care domain, doctors received higher scores.

In terms of communication, understanding children’s needs and responding promptly, providing more support and communication with the child and family, and delivering accurate information about the child’s condition by nurses are priorities for improving the quality of care and enhancing parental satisfaction. To this end, while reinforcing the positive aspects mentioned, it is also necessary to improve communication between nurses and the child and family. It is suggested that improvement measures be implemented to increase knowledge, change attitudes, and enhance nurses’ performance in the area of professional communication skills with children and families, considering generational differences among nurses and utilizing modern educational methods.

Conclusion

Professional care, effective physician-parent communication, accurate information about the child’s condition and treatment, and a clean environment are key factors in parental satisfaction.

Acknowledgements: This article is the result of Mr. Shafaq Tofghi’s doctoral thesis in the field of pediatric nursing. The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Research Assistant at Iran University of Medical Sciences for approving and financially supporting the thesis. The researchers would especially like to thank the parents who participated in the study, as well as the managers, nurses, and doctors of the pediatric intensive care unit at the educational and medical centers involved.

Ethical Permissions: Ethics code IR.IUMS.REC.1397.057 was issued by the Research Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences to conduct this research.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Sabeti F (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (60%); Towfiq Sh (Second Author), Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%)

Funding/Support: The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Research Assistant at Iran University of Medical Sciences for approving and financially supporting the research.

Keywords:

References

1. Roberti SM, Fitzpatrick JJ. Assessing family satisfaction with care of critically ill patients: A pilot study. Crit Care Nurse. 2010;30(6):18-26. [Link] [DOI:10.4037/ccn2010448]

2. Foldager Jeppesen S, Vilhjálmsson R, Åvik Persson H, Kristensson Hallström I. Parental satisfaction with paediatric care with and without the support of an eHealth device: A quasi-experimental study in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):41. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-023-10398-7]

3. Graham B. Defining and measuring patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(9):929-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.07.109]

4. Kash B, McKahan M. The evolution of measuring patient satisfaction. J Prim Health Care Gen Pract. 2017;1(1). [Link]

5. Weissenstein A, Straeter A, Villalon G, Luchter E, Bittmann S. Parent satisfaction with a pediatric practice in Germany: A questionnaire-based study. Ital J Pediatr. 2011;37(1):31. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1824-7288-37-31]

6. Ammentorp J, Mainz J, Sabroe S. Parents' priorities and satisfaction with acute pediatric care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(2):127-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/archpedi.159.2.127]

7. Tsironi S, Koulierakis G. Factors affecting parents' satisfaction with pediatric wards. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2019;16(2):212-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jjns.12239]

8. Salmani N, Abbaszadeh A, Rasouli M, Hasanvand S. The process of satisfaction with nursing care in parents of hospitalized children: A grounded theory study. J Pediatr Perspect. 2015;3(6.1):1021-32. [Link]

9. Oztas G, Akca SO. Levels of nursing support and satisfaction of parents with children having pediatric inpatient care. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;77:e24-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2024.03.004]

10. Sahota LK, Agrawal N, Kumar R, Simalti AK. A survey of factors affecting parental satisfaction regarding patient care in pediatric intensive care unit at a tertiary hospital in Northern India. J Pediatr Crit Care. 2025;12(1):14-9. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jpcc.jpcc_79_24]

11. Curtis K, Foster K, Mitchell R, Van C. Models of care delivery for families of critically ill children: an integrative review of international literature. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(3):330-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2015.11.009]

12. Abuqamar M, Arabiat DH, Holmes S. Parents' perceived satisfaction of care, communication and environment of the pediatric intensive care units at a tertiary children's hospital. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(3):e177-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2015.12.009]

13. Ebrahim S, Singh S, Parshuram CS. Parental satisfaction, involvement, and presence after pediatric intensive care unit admission. J Crit Care. 2013;28(1):40-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.011]

14. Terp K, Jakobsson U, Weis J, Lundqvist P. Evaluation of satisfaction with care in paediatric intensive care units: Swedish parents' perspective. Nurs Crit Care. 2025;30(4):e70086. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/nicc.70086]

15. De La Oliva P, Cambra-Lasaosa FJ, Quintana-Diaz M, Rey-Galan C, Sánchez-Díaz JI, Martín-Delgado MC, et al. Admission, discharge and triage guidelines for paediatric intensive care units in Spain. Med Intensiva. 2018;42(4):235-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.medine.2017.10.009]

16. Cintra CdC, Garcia PCR, Brandi S, Crestani F, Lessa ARD, Cunha MLdR. Parents' satisfaction with care in pediatric intensive care units. REVISTA GAUCHA DE ENFERMAGEM. 2022;43:e20210003. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/1983-1447.2022.20210003.pt]

17. McPherson ML, Sachdeva RC, Jefferson LS. Development of a survey to measure parent satisfaction in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(8):3009-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00003246-200008000-00055]

18. Hinton P, McMurray I, Brownlow C, Terry PC. Using SPSS to analyse questionnaires: Reliability. In: SPSS explained. London: Routledge; 2004. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9780203642597]

19. Mahmoudzadeh M, Mohammadi MA, Moshfeghi S, Dadkhah B. Investigating the relationship between ethical care of nurses and the satisfaction of parents of children hospitalized in Ardabil children's hospital 2024: A (cross-sectional) study. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2025;33(1):72-81. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32592/ajnmc.33.1.72]

20. Appiah EO, Appiah S, Kontoh S, Mensah S, Awuah DB, Menlah A, et al. Pediatric nurse-patient communication practices at Pentecost Hospital, Madina: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2022;9(4):481-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2022.09.009]

21. Haley B, Heo S, Wright P, Barone C, Rettiganti MR, Anders M. Relationships among active listening, self-awareness, empathy, and patient-centered care in associate and baccalaureate degree nursing students. NursingPlus Open. 2017;3:11-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.npls.2017.05.001]

22. Elbilgahy AA, Hashem SF, Alemam DSAEK. Mothers' satisfaction with care provided for their children in pediatric intensive care unit. Middle East J Nurs. 2019;13(2):17-28. [Link] [DOI:10.5742/MEJN.2019.93636]

23. Martinez EA, Tocantins FR, Souza SRd. The specificities of communication in child nursing care. REVISTA GAUCHA DE ENFERMAGEM. 2013;34(1):37-44. [Portuguese] [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S1983-14472013000100005]

24. Hsu LL, Chang WH, Hsieh SI. The effects of scenario-based simulation course training on nurses' communication competence and self-efficacy: A randomized controlled trial. J Prof Nurs. 2015;31(1):37-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.05.007]

25. Duzkaya DS, Uysal G, Akay H. Nursing perception of the children hospitalized in a university hospital. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;152:362-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.212]

26. Alzawad Z, Lewis FM, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Howells AJ. A qualitative study of parents' experiences in the pediatric intensive care unit: Riding a roller coaster. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;51:8-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2019.11.015]

27. MacKay LJ, Chang U, Kreiter E, Nickel E, Kamke J, Bahia R, et al. Exploration of trust between pediatric nurses and children with a medical diagnosis and their caregivers on inpatient care units: A scoping review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;78:e1-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2024.05.030]

28. Hosseinian M, Shahshahani MS, Adib-Hajbagheri M. Mothers satisfaction of hospital care in the pediatric ward of Kashan Shahid Beheshti hospital during 2010-11. Feyz Med Sci J. 2011;15(2):153-60. [Persian] [Link]