Volume 6, Issue 1 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(1): 39-46 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1402.161

History

Received: 2025/02/9 | Accepted: 2025/03/16 | Published: 2025/03/25

Received: 2025/02/9 | Accepted: 2025/03/16 | Published: 2025/03/25

How to cite this article

Nadi E, Bakhtiarpour S, Makvandi B, Asgari P. The Relationship Between Paternal Family Health and Stress with Subjective Well-Being in Married Students Mediated by Marital Satisfaction. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (1) :39-46

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-384-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-384-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (103 Views)

Introduction

The rising incidence of mental disorders, particularly among young adults and university students, has been a notable trend in recent years, significantly affecting their subjective well-being [1]. The attainment of subjective well-being is recognized as essential for positive social functioning, enabling both individual and societal adaptation to life’s challenges [2]. As a dimension of the mental health continuum, subjective well-being represents the optimal and positive aspect of individual health, distinct from yet interconnected with mental disorders, which constitute the negative aspect. Consequently, identifying the key determinants and antecedents of subjective well-being is crucial for safeguarding students against mental disorders and promoting their positive functioning [3]. Given the conceptual diversity of well-being within the national context and the growing prevalence of mental disorders in the general population, research is warranted to explore a broader understanding of subjective well-being in diverse settings such as universities [4].

Literature examining well-being consistently identifies the quality of interpersonal relationships (parents, family, and friends) as a pivotal determinant [5]. Subjective well-being, defined as an individual's holistic evaluation of life quality based on personal standards, is characterized by subjectivity, stability, and comprehensiveness. It is assessed through ongoing subjective evaluations, reflecting personal perspectives and the experience of diverse emotions [6]. Consequently, subjective well-being can be conceptualized as encompassing affective components (high positive affect, low negative affect) and cognitive components (general and domain-specific life satisfaction) [7]. However, the exploration of factors that positively or negatively influence subjective well-being remains a core research focus. Recent studies have emphasized the significance of familial, psychological, and social determinants in shaping subjective well-being, with particular attention to the roles of paternal family health, parenting stress, and marital satisfaction [8].

Literature examining well-being consistently identifies the quality of interpersonal relationships (with parents, family, and friends) as a pivotal determinant [5]. Subjective well-being, defined as an individual’s holistic evaluation of life quality based on personal standards, is characterized by subjectivity, stability, and comprehensiveness. It is assessed through ongoing subjective evaluations that reflect personal perspectives and the experience of diverse emotions [6]. Consequently, subjective well-being can be conceptualized as encompassing affective components (high positive affect and low negative affect) and cognitive components (general and domain-specific life satisfaction) [7]. However, the exploration of factors that positively or negatively influence subjective well-being remains a core focus of research. Recent studies have emphasized the significance of familial, psychological, and social determinants in shaping subjective well-being, with particular attention to the roles of paternal family health, parenting stress, and marital satisfaction [8].

Disruptions or challenges to family health can amplify stress and negatively affect well-being [12]. Empirical evidence indicates that stressors exert a substantial influence on both short- and long-term mental health, with parental stress—a particularly salient stressor—significantly diminishing subjective well-being [13]. Parental stress encompasses the perceived strain arising from parental responsibilities, such as managing sleep patterns, meal preparation, and coordinating children’s extracurricular activities. This strain manifests as psychological or emotional pressure that can lead to distress and compromise well-being [14]. Choi et al. [15] underscore the inverse relationship between stress and subjective well-being, demonstrating that increased stress correlates with decreased well-being, while reduced stress facilitates higher well-being. Furthermore, parental stress can impact couples’ interpersonal dynamics and their perception of marital relationship quality and satisfaction. There is a negative association between stress and marital satisfaction [16]. Conversely, marital satisfaction, functioning as a stress buffer, can enhance subjective well-being by cultivating a supportive environment that enables individuals to manage external stressors more effectively [17].

Marital satisfaction is posited to enhance couples’ well-being through the facilitation of marital harmony. It is fundamentally defined as the congruence between perceived and desired marital states, reflecting an individual’s comprehensive and subjective evaluation of their marriage [18]. Interpersonal relationships, including marital ones, are characterized by reciprocal interactions and exchanges. Within the framework of family studies, a core tenet of behavioral theory posits that positive marital behaviors elevate spouses’ overall marital sentiment, while negative behaviors erode positive affect and negatively impact relationship perceptions [19]. Consequently, marital satisfaction was hypothesized to mediate the relationship between research parameters and determinants of subjective well-being. Prior research has established associations between family health, stress, and marital satisfaction. Expanding upon existing literature that documents the impact of family health, stress, and marital satisfaction on well-being, this study aimed to examine these influences within a novel population [20, 21]. Specifically, by investigating the contributions of paternal family health, parenting stress, and marital satisfaction to subjective well-being, this research sought to advance a more nuanced understanding of this construct within a new empirical context. Accordingly, among married students, this study investigated whether marital satisfaction mediated the relationships among paternal family health, parental stress, and subjective well-being.

Instrument and Methods

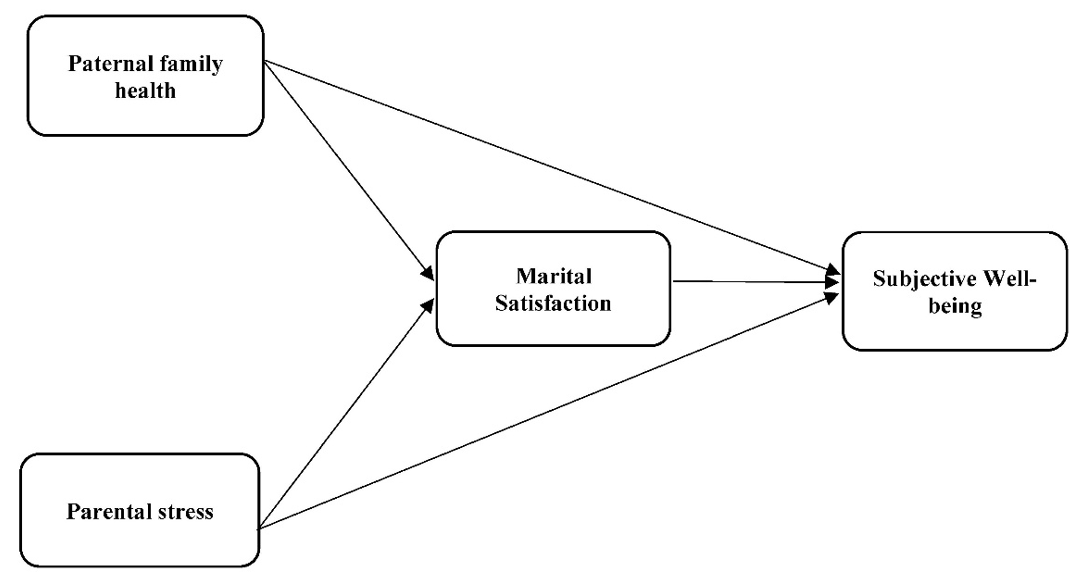

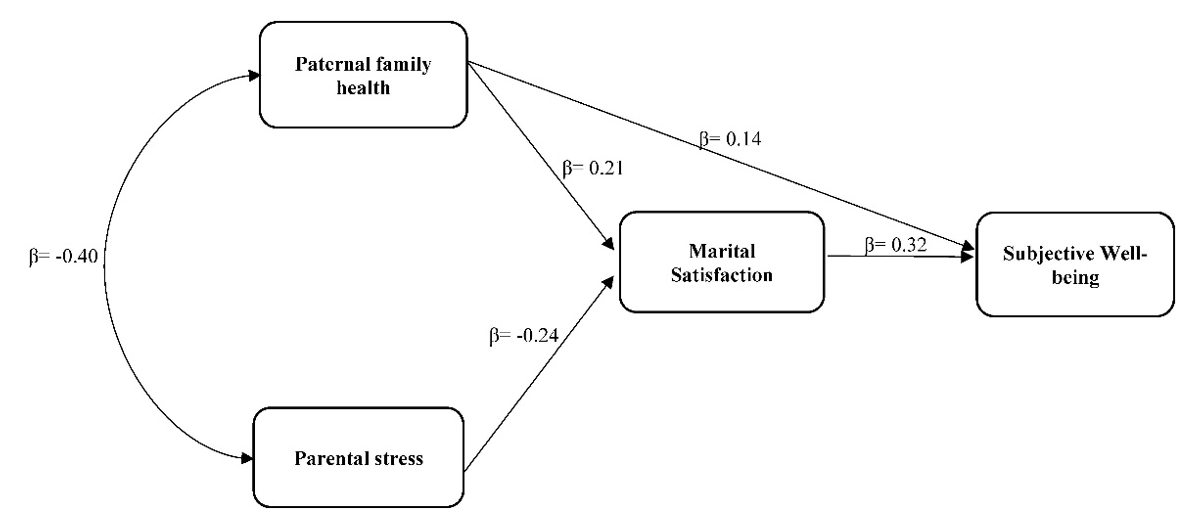

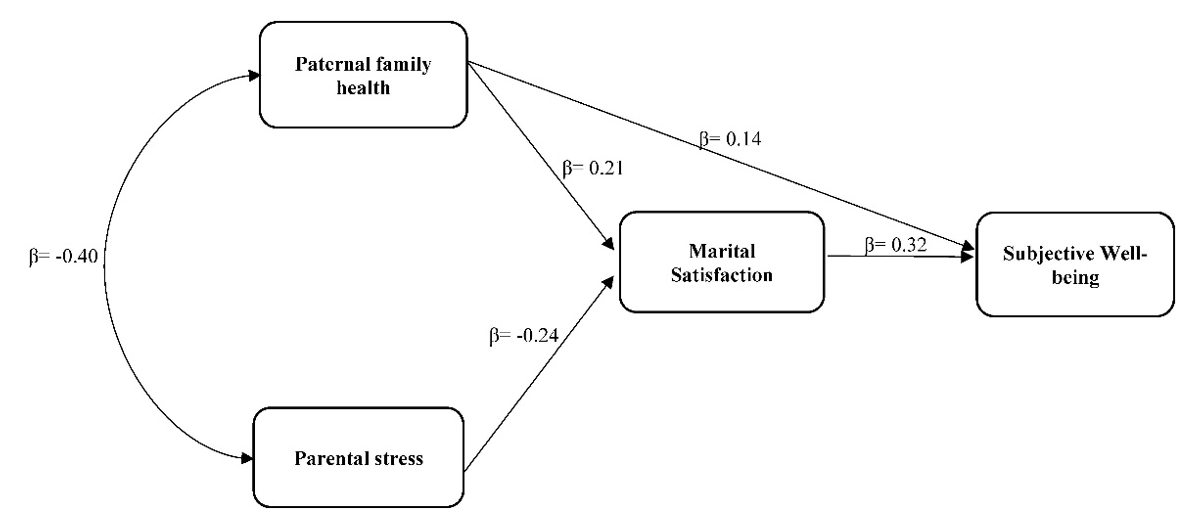

This research adopted a descriptive-correlational approach, utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the associations among paternal family health, parental stress, and subjective well-being, while emphasizing the mediating role of marital satisfaction. The study targeted female students at the Islamic Azad University of Rasht, Iran, during the academic year 2023 (Figure 1). Following institutional approval, a convenience sampling method was employed. The sample size was calculated using G*Power software, resulting in the selection of 473 participants who met the inclusion criteria, including voluntary participation, provision of informed consent, current enrollment at the university, and female gender. The exclusion criteria included withdrawal from the study, incomplete questionnaire responses (with more than 10% missing data), or an evident lack of engagement during data collection. Participants received a comprehensive briefing prior to completing the research tools, and measures were implemented to address potential sensitivities.

Figure 1. The conceptual model

Research instrument

Subjective Well-Being Scale (SWS)

This tool is designed to measure the emotional, psychological, and social facets of well-being, comprising 45 items. The first 12 items assess emotional well-being, the subsequent 18 items evaluate psychological well-being, and the final 15 items target social well-being [22]. The SWS has exhibited adequate face validity, internal consistency, and overall reliability [23]. Ebrahimi et al. [23] documented a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80 for the scale. In the present study, the SWS’s reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha, resulting in a coefficient of 0.83.

Family-of-Origin Scale (FOS)

The Family-of-Origin Scale (FOS), developed by Hovestadt et al. [24], comprises 40 items that assess ten distinct components, including clarity of expression, responsibility, respect for others, openness to others, acceptance of separation and failure, encouragement of emotional expression, creation of a warm family environment, non-stressful conflict resolution, encouragement and empathy, and the establishment of interpersonal trust. These components collectively measure two overarching dimensions, namely autonomy and intimacy. Responses are recorded on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from one (strongly agree) to five (strongly disagree). Rajabi et al. [25] reported a high reliability coefficient of 0.93 for this scale.

Parenting Stress Index (PSI)

The Parenting Stress Index (PSI), a 36-item measure evaluating parental stress across child, parent, and family domains, was employed in this study. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting increased stress [26]. The Persian version of the PSI has demonstrated satisfactory reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 [27].

Marital Satisfaction Scale (MSS)

To evaluate marital satisfaction, the 35-item MSS was employed, focusing on satisfaction, communication, and conflict resolution [28]. While the ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale encompasses a wider range of marital domains, both scales utilize a five-point Likert scale. The MSS exhibited satisfactory internal consistency in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 [29].

Data analysis

To examine the proposed relationships among latent parameters, including the mediating role of marital satisfaction, SEM was conducted using SPSS 26 and Amos-26, following data cleaning and assumption testing. Bootstrapping was applied to generate reliable estimates of indirect effects, specifically addressing the mediation.

Findings

The sample’s age distribution revealed that 24.53% (n=116) of participants were aged 20-25, 55.60% (n=263) were aged 25-30, and 19.87% (n=94) were aged 30-35. In terms of educational attainment, 45.67% (n=216) were undergraduates, 47.87% (n=226) were graduate students, and 6.55% (n=31) were doctoral candidates.

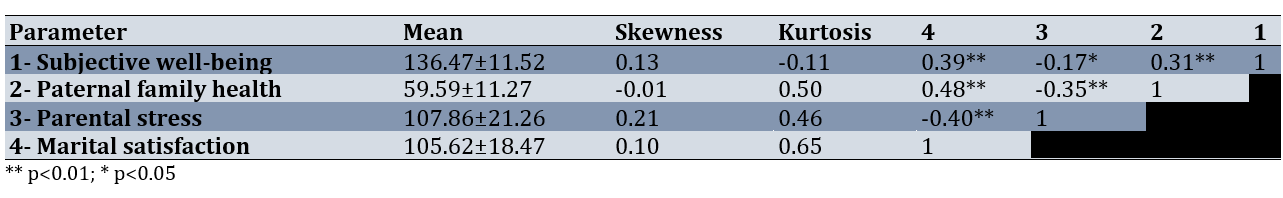

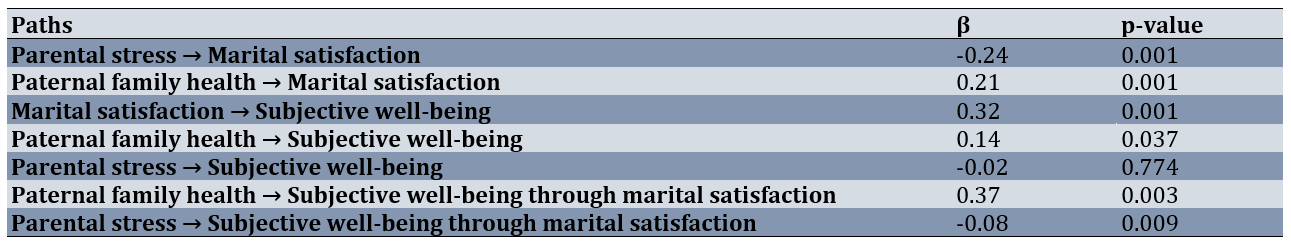

Subjective well-being exhibited a significant positive correlation with paternal family health (r=0.31, p<0.01) and marital satisfaction (r=0.39, p<0.01) while showing a significant negative correlation with parental stress (r=-0.17, p<0.05). Paternal family health was positively correlated with marital satisfaction (r=0.48, p<0.01) and negatively correlated with parental stress (r=-0.35, p<0.01). Finally, marital satisfaction displayed a significant negative correlation with parental stress (r=-0.40, p<0.01). These findings suggest that higher paternal family health and marital satisfaction are associated with increased subjective well-5/6/2025being, while higher parental stress is associated with decreased subjective well-being (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean, Skewness, Kurtosis, and Pearson correlation coefficients of the parameters

To test the proposed model, SEM was conducted following a preliminary assessment of fundamental assumptions. Normality, evaluated through skewness and kurtosis, was confirmed for all parameters. Multicollinearity, assessed using tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF), was not detected. The Durbin-Watson statistic (1.98) indicated that the independence of errors assumption was met.

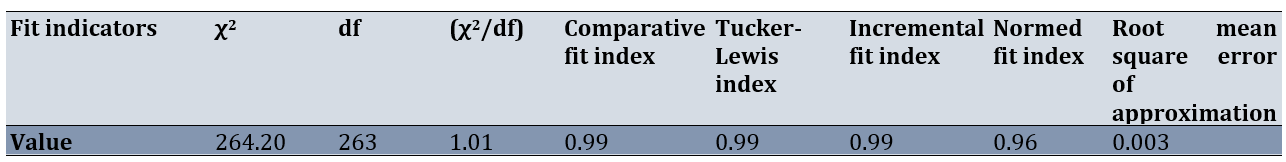

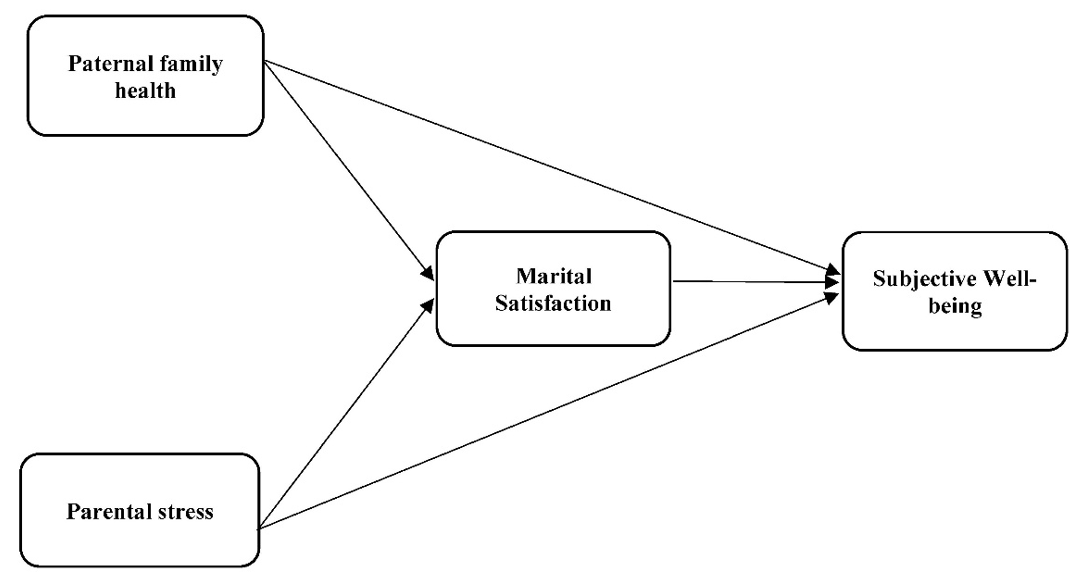

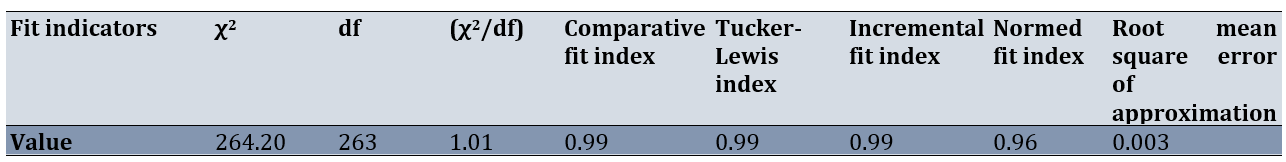

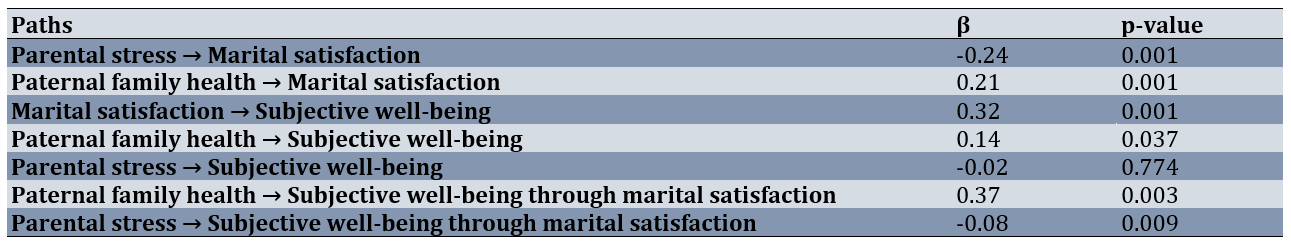

The adequacy of the hypothesized model’s fit to the observed data was assessed using a range of fit indices, including normalized chi-square (χ²), normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). All indices indicated an acceptable model fit (Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2. Fit indicators of the final model

Figure 2. The final model of the study.

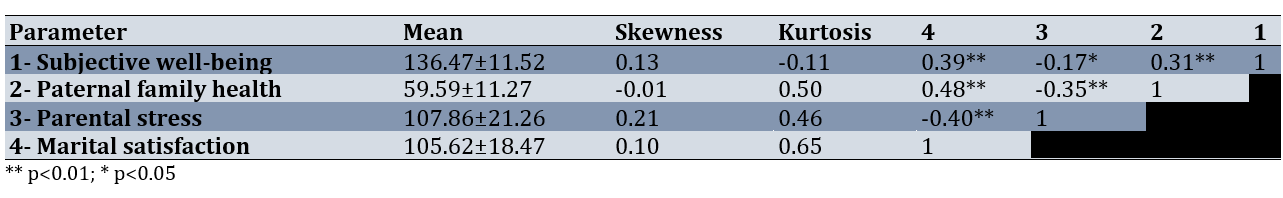

The direct effects revealed that parental stress significantly and negatively predicted marital satisfaction (β=-0.24, p<0.001), whereas paternal family health significantly and positively predicted both marital satisfaction (β=0.21, p<0.001) and subjective well-being (β=0.14, p=0.037). Furthermore, marital satisfaction significantly and positively predicted subjective well-being (β=0.32, p<0.001). Parental stress did not exhibit a significant direct effect on subjective well-being (β=-0.02, p=0.774). However, significant indirect effects were observed; paternal family health positively influenced subjective well-being through marital satisfaction (β=0.37, p=0.003), and parental stress negatively influenced subjective well-being through marital satisfaction (β=-0.08, p=0.009). Thus, marital satisfaction mediated the relationships between both paternal family health and parental stress, respectively, on subjective well-being among married students (Table 3).

Table 3. Direct and indirect path in the final model

Discussion

The present study examined the mediating influence of marital satisfaction on the relationships linking paternal family health and parental stress to subjective well-being among married student participants. There was an inverse association between parental stress and marital satisfaction, indicating that heightened parental stress negatively impacts marital satisfaction. This result aligns with prior research, notably Dong et al. [30], reporting a negative correlation between childcare pressure and stress and marital satisfaction. Similarly, Brisini and Solomon [31] found that relational distress, characterized by diminished effective reasoning and elevated parenting stress, is associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction.

This relationship can be attributed to the multifaceted challenges parents encounter during child-rearing, including the transition from spousal to parental roles and the financial strain associated with parenting. Successfully navigating these responsibilities directly influences the quality of this life stage. Even in initially harmonious marriages, inadequate management of these tasks can lead to a decline in marital quality and eventual relationship deterioration. Research has identified parental stress as a significant contributor to reduced marital satisfaction during this period [30]. Conversely, couples experiencing high marital satisfaction are more inclined to provide mutual emotional support. This support can mitigate feelings of isolation and anxiety stemming from parental responsibilities. Parental feelings of being understood and supported by their partners enhance their capacity to effectively manage the demands of parenting.

There was also a significant relationship between paternal family health and marital satisfaction. This finding aligns with observations by Arianfar and Rasouli [20], reporting a direct influence of paternal family health on marital satisfaction. However, Hejazi et al. [32] report a contrasting result, indicating a negative association between family-of-origin health and marital satisfaction.

To elucidate this finding, attachment theory posits that children develop coping strategies and distress regulation through interactions with primary caregivers, seeking intimacy and closeness consistent with these experiences [32]. Consequently, family-of-origin health appears to indirectly enhance marital satisfaction by shaping parental marital dynamics. Furthermore, Bowen’s multigenerational theory suggests that individuals acquire fundamental interpersonal relationship patterns within their families of origin, and marital and familial challenges often reflect unresolved relational issues from these formative experiences. Communication patterns within the family of origin, including interaction styles, mutual understanding, and decision-making processes, influence individuals’ ability to adapt to future relationships and extra-familial contexts [20]. In essence, individuals with healthy family-of-origin experiences are more likely to demonstrate attentiveness to their spouse’s needs and expectations, engaging in empathetic and constructive interactions, which ultimately foster marital satisfaction. Moreover, healthy family-of-origin dynamics facilitate constructive conflict resolution, contributing to heightened marital satisfaction.

There was a positive association between marital satisfaction and subjective well-being, indicating that elevated marital satisfaction predicts greater subjective well-being. This finding is consistent with prior research, including a study by Ansari Ardali et al. [33], reporting a positive correlation between marital satisfaction and well-being.

This association can be explained by the role of marital satisfaction in facilitating a balance between personal needs and spousal/parental responsibilities. This equilibrium not only contributes to successful marital functioning but also supports individual personal growth. Consequently, it leads to enhanced interpersonal relationships, reduced relational stress, increased marital happiness, and strengthened emotional bonds. This synergy of relational satisfaction and personal development appears to fulfill the prerequisites for enhancing subjective well-being [33].

A supportive spouse serves as a critical source of social support, positively correlating with subjective well-being. However, not all marriages are more advantageous than singlehood in terms of subjective well-being. Marital conflict, separation, or divorce can precipitate psychological and health problems. Remaining in an unsatisfactory marriage is significantly associated with diminished happiness, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and overall health, as well as increased psychological distress. Furthermore, remaining in an unhappy marriage is often more detrimental than divorce, as individuals dissatisfied with their marriages report lower contentment compared to divorced or remarried individuals. Thus, maintaining a satisfying marital relationship is crucial for achieving, enhancing, and sustaining high subjective well-being.

There was also a significant association between paternal family health and subjective well-being. This result is consistent with observations by Kuo and Chiu [34], indicating that family atmosphere directly impacts individual well-being. Likewise, the findings of Pitonyak et al. [8], which link functional patterns of the family of origin to health and well-being, and Crandall et al. [35], which associate negative familial mental impacts with increased psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety (negative aspects of mental health and well-being), corroborate this finding.

To elucidate this, subjective well-being encompasses the absence of mental distress, overall life satisfaction, and the pursuit of self-actualization. It is recognized as a critical factor in resilience against psychological harm and illness. However, as evidence indicates, it is also influenced by various factors, including family health. Paternal family health fosters subjective well-being among family members by establishing a supportive, stable, and meaningful environment. This influence operates through mechanisms, such as emotional support, stress management, modeling healthy behaviors, and promoting a sense of belonging, thereby predicting and enhancing subjective well-being. Consequently, attending to paternal family health not only improves familial relationships but also promotes the mental and emotional health of family members.

Furthermore, paternal family health is frequently associated with stability and structure. An environment characterized by clear rules, explicit expectations, and consistent daily routines provides children with a sense of security and predictability. This stability contributes to reduced anxiety and enhanced feelings of control over life, both of which are key determinants of subjective well-being [8]. Consequently, healthy families typically facilitate the early identification and management of psychological issues. This proactive intervention may contribute to the maintenance of subjective well-being.

The current study’s findings revealed no significant direct relationship between parental stress and subjective well-being. This result diverges from previous research, including a study by Sharda et al. [36], but aligns with observations by Russell et al. [37].

This discrepancy can be attributed to the complex, multidimensional nature of subjective well-being, which is influenced by a confluence of factors, including interpersonal and environmental interactions. Consequently, parental stress alone may not serve as a precise predictor of subjective well-being. Other salient factors, such as social support from the family of origin and the quality of the marital relationship, play crucial roles. For instance, parents with robust social support networks [8] or high marital satisfaction may exhibit higher levels of subjective well-being, even in the presence of parental stress. Furthermore, individual psychological resources, such as coping strategies and emotion regulation, significantly modulate the association between parental stress and subjective well-being. Effective coping mechanisms can attenuate the adverse effects of stress [37]. Mindful parenting and positive mental health are also associated with diminished parental stress. It is plausible that individuals exhibit heterogeneous responses to stress. Some parents may perceive stress as a catalyst for growth and demonstrate enhanced adaptive capacity, while others may experience a decline in subjective well-being under stress. These variations are contingent upon other influential psychological factors.

The indirect path analysis revealed that marital satisfaction mediates the relationship between paternal family health and subjective well-being. This result aligns with prior research, including a study by Iwasa et al. [38], demonstrating the mediating role of marital satisfaction in the association between family dynamics and subjective well-being.

This finding can be explained by the dual influence of family support, encompassing both instrumental and emotional dimensions, on subjective well-being. Marital satisfaction acts as a significant mediator in this process, suggesting that the quality of the marital relationship amplifies the beneficial effects of family support on psychological well-being. Moreover, the quality of family life is substantially linked to couples’ subjective well-being, and a satisfying marital relationship can create a conducive environment for enhancing well-being by potentiating positive family effects [38]. Specifically, marital satisfaction functions as a critical intermediary through which paternal family health impacts family members’ subjective well-being. A healthy and supportive paternal family facilitates constructive interactions, rooted in healthy communication patterns, within marital relationships, thereby fostering increased marital satisfaction. Subsequently, elevated marital satisfaction contributes to enhanced subjective well-being by enabling couples to mitigate stress and cultivate happiness in their shared lives.

There was an indirect relationship between parental stress and subjective well-being, mediated by marital satisfaction. Specifically, parental stress was found to negatively influence marital satisfaction, which subsequently had a positive impact on and enhanced subjective well-being. This result is consistent with prior research documenting the adverse effects of parental stress on marital satisfaction [30, 31] and the beneficial effects of marital satisfaction on subjective well-being [33].

This mediation can be explained by the observation that couples exhibiting higher marital satisfaction tend to address parenting and spousal challenges with greater support and responsibility, leading to a reduction in parental stress. The attenuation of anxiety and tension associated with parental responsibilities enables parents to manage child-rearing demands more effectively. Consequently, marital satisfaction, by buffering subjective well-being against the negative impacts of parental stress, creates a conducive environment for enhancement.

Several limitations warrant consideration. Firstly, the use of convenience sampling in this study may have introduced potential bias into the findings. Secondly, the exclusion of male participants and the consequent inability to account for gender differences represent significant limitations that should be acknowledged.

In conclusion, this study elucidates the complex interplay between paternal family health, parental stress, marital satisfaction, and subjective well-being within the studied population. The significant positive direct influence of paternal family health on subjective well-being underscores the importance of positive familial dynamics in fostering individual well-being. Furthermore, the mediating role of marital satisfaction in this relationship highlights its crucial function as a conduit through which healthy family environments translate into enhanced subjective well-being. Conversely, while parental stress did not directly impact subjective well-being, its significant negative indirect influence through marital satisfaction suggests that parental stress erodes marital satisfaction, subsequently diminishing subjective well-being. The robust positive direct relationship between marital satisfaction and subjective well-being reinforces the established literature on the critical role of marital quality in promoting individual psychological health. These findings collectively emphasize the systemic nature of well-being, where familial and relational factors interact to shape individual subjective experiences.

Conclusion

Paternal family health positively affects subjective well-being, mediated by marital satisfaction, while parental stress negatively impacts well-being through reduced marital satisfaction.

Acknowledgments: The researchers would like to thank all the individuals who participated in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This study received ethical approval from the Ethical Committee of the Islamic Azad University-Ahvaz Branch (reference code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1402.161).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Nadi E (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Bakhtiarpour S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Makvandi B (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/ Statistical Analyst (20%); Asgari P (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This study did not receive any funding.

The rising incidence of mental disorders, particularly among young adults and university students, has been a notable trend in recent years, significantly affecting their subjective well-being [1]. The attainment of subjective well-being is recognized as essential for positive social functioning, enabling both individual and societal adaptation to life’s challenges [2]. As a dimension of the mental health continuum, subjective well-being represents the optimal and positive aspect of individual health, distinct from yet interconnected with mental disorders, which constitute the negative aspect. Consequently, identifying the key determinants and antecedents of subjective well-being is crucial for safeguarding students against mental disorders and promoting their positive functioning [3]. Given the conceptual diversity of well-being within the national context and the growing prevalence of mental disorders in the general population, research is warranted to explore a broader understanding of subjective well-being in diverse settings such as universities [4].

Literature examining well-being consistently identifies the quality of interpersonal relationships (parents, family, and friends) as a pivotal determinant [5]. Subjective well-being, defined as an individual's holistic evaluation of life quality based on personal standards, is characterized by subjectivity, stability, and comprehensiveness. It is assessed through ongoing subjective evaluations, reflecting personal perspectives and the experience of diverse emotions [6]. Consequently, subjective well-being can be conceptualized as encompassing affective components (high positive affect, low negative affect) and cognitive components (general and domain-specific life satisfaction) [7]. However, the exploration of factors that positively or negatively influence subjective well-being remains a core research focus. Recent studies have emphasized the significance of familial, psychological, and social determinants in shaping subjective well-being, with particular attention to the roles of paternal family health, parenting stress, and marital satisfaction [8].

Literature examining well-being consistently identifies the quality of interpersonal relationships (with parents, family, and friends) as a pivotal determinant [5]. Subjective well-being, defined as an individual’s holistic evaluation of life quality based on personal standards, is characterized by subjectivity, stability, and comprehensiveness. It is assessed through ongoing subjective evaluations that reflect personal perspectives and the experience of diverse emotions [6]. Consequently, subjective well-being can be conceptualized as encompassing affective components (high positive affect and low negative affect) and cognitive components (general and domain-specific life satisfaction) [7]. However, the exploration of factors that positively or negatively influence subjective well-being remains a core focus of research. Recent studies have emphasized the significance of familial, psychological, and social determinants in shaping subjective well-being, with particular attention to the roles of paternal family health, parenting stress, and marital satisfaction [8].

Disruptions or challenges to family health can amplify stress and negatively affect well-being [12]. Empirical evidence indicates that stressors exert a substantial influence on both short- and long-term mental health, with parental stress—a particularly salient stressor—significantly diminishing subjective well-being [13]. Parental stress encompasses the perceived strain arising from parental responsibilities, such as managing sleep patterns, meal preparation, and coordinating children’s extracurricular activities. This strain manifests as psychological or emotional pressure that can lead to distress and compromise well-being [14]. Choi et al. [15] underscore the inverse relationship between stress and subjective well-being, demonstrating that increased stress correlates with decreased well-being, while reduced stress facilitates higher well-being. Furthermore, parental stress can impact couples’ interpersonal dynamics and their perception of marital relationship quality and satisfaction. There is a negative association between stress and marital satisfaction [16]. Conversely, marital satisfaction, functioning as a stress buffer, can enhance subjective well-being by cultivating a supportive environment that enables individuals to manage external stressors more effectively [17].

Marital satisfaction is posited to enhance couples’ well-being through the facilitation of marital harmony. It is fundamentally defined as the congruence between perceived and desired marital states, reflecting an individual’s comprehensive and subjective evaluation of their marriage [18]. Interpersonal relationships, including marital ones, are characterized by reciprocal interactions and exchanges. Within the framework of family studies, a core tenet of behavioral theory posits that positive marital behaviors elevate spouses’ overall marital sentiment, while negative behaviors erode positive affect and negatively impact relationship perceptions [19]. Consequently, marital satisfaction was hypothesized to mediate the relationship between research parameters and determinants of subjective well-being. Prior research has established associations between family health, stress, and marital satisfaction. Expanding upon existing literature that documents the impact of family health, stress, and marital satisfaction on well-being, this study aimed to examine these influences within a novel population [20, 21]. Specifically, by investigating the contributions of paternal family health, parenting stress, and marital satisfaction to subjective well-being, this research sought to advance a more nuanced understanding of this construct within a new empirical context. Accordingly, among married students, this study investigated whether marital satisfaction mediated the relationships among paternal family health, parental stress, and subjective well-being.

Instrument and Methods

This research adopted a descriptive-correlational approach, utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the associations among paternal family health, parental stress, and subjective well-being, while emphasizing the mediating role of marital satisfaction. The study targeted female students at the Islamic Azad University of Rasht, Iran, during the academic year 2023 (Figure 1). Following institutional approval, a convenience sampling method was employed. The sample size was calculated using G*Power software, resulting in the selection of 473 participants who met the inclusion criteria, including voluntary participation, provision of informed consent, current enrollment at the university, and female gender. The exclusion criteria included withdrawal from the study, incomplete questionnaire responses (with more than 10% missing data), or an evident lack of engagement during data collection. Participants received a comprehensive briefing prior to completing the research tools, and measures were implemented to address potential sensitivities.

Figure 1. The conceptual model

Research instrument

Subjective Well-Being Scale (SWS)

This tool is designed to measure the emotional, psychological, and social facets of well-being, comprising 45 items. The first 12 items assess emotional well-being, the subsequent 18 items evaluate psychological well-being, and the final 15 items target social well-being [22]. The SWS has exhibited adequate face validity, internal consistency, and overall reliability [23]. Ebrahimi et al. [23] documented a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80 for the scale. In the present study, the SWS’s reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha, resulting in a coefficient of 0.83.

Family-of-Origin Scale (FOS)

The Family-of-Origin Scale (FOS), developed by Hovestadt et al. [24], comprises 40 items that assess ten distinct components, including clarity of expression, responsibility, respect for others, openness to others, acceptance of separation and failure, encouragement of emotional expression, creation of a warm family environment, non-stressful conflict resolution, encouragement and empathy, and the establishment of interpersonal trust. These components collectively measure two overarching dimensions, namely autonomy and intimacy. Responses are recorded on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from one (strongly agree) to five (strongly disagree). Rajabi et al. [25] reported a high reliability coefficient of 0.93 for this scale.

Parenting Stress Index (PSI)

The Parenting Stress Index (PSI), a 36-item measure evaluating parental stress across child, parent, and family domains, was employed in this study. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting increased stress [26]. The Persian version of the PSI has demonstrated satisfactory reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 [27].

Marital Satisfaction Scale (MSS)

To evaluate marital satisfaction, the 35-item MSS was employed, focusing on satisfaction, communication, and conflict resolution [28]. While the ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale encompasses a wider range of marital domains, both scales utilize a five-point Likert scale. The MSS exhibited satisfactory internal consistency in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 [29].

Data analysis

To examine the proposed relationships among latent parameters, including the mediating role of marital satisfaction, SEM was conducted using SPSS 26 and Amos-26, following data cleaning and assumption testing. Bootstrapping was applied to generate reliable estimates of indirect effects, specifically addressing the mediation.

Findings

The sample’s age distribution revealed that 24.53% (n=116) of participants were aged 20-25, 55.60% (n=263) were aged 25-30, and 19.87% (n=94) were aged 30-35. In terms of educational attainment, 45.67% (n=216) were undergraduates, 47.87% (n=226) were graduate students, and 6.55% (n=31) were doctoral candidates.

Subjective well-being exhibited a significant positive correlation with paternal family health (r=0.31, p<0.01) and marital satisfaction (r=0.39, p<0.01) while showing a significant negative correlation with parental stress (r=-0.17, p<0.05). Paternal family health was positively correlated with marital satisfaction (r=0.48, p<0.01) and negatively correlated with parental stress (r=-0.35, p<0.01). Finally, marital satisfaction displayed a significant negative correlation with parental stress (r=-0.40, p<0.01). These findings suggest that higher paternal family health and marital satisfaction are associated with increased subjective well-5/6/2025being, while higher parental stress is associated with decreased subjective well-being (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean, Skewness, Kurtosis, and Pearson correlation coefficients of the parameters

To test the proposed model, SEM was conducted following a preliminary assessment of fundamental assumptions. Normality, evaluated through skewness and kurtosis, was confirmed for all parameters. Multicollinearity, assessed using tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF), was not detected. The Durbin-Watson statistic (1.98) indicated that the independence of errors assumption was met.

The adequacy of the hypothesized model’s fit to the observed data was assessed using a range of fit indices, including normalized chi-square (χ²), normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). All indices indicated an acceptable model fit (Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2. Fit indicators of the final model

Figure 2. The final model of the study.

The direct effects revealed that parental stress significantly and negatively predicted marital satisfaction (β=-0.24, p<0.001), whereas paternal family health significantly and positively predicted both marital satisfaction (β=0.21, p<0.001) and subjective well-being (β=0.14, p=0.037). Furthermore, marital satisfaction significantly and positively predicted subjective well-being (β=0.32, p<0.001). Parental stress did not exhibit a significant direct effect on subjective well-being (β=-0.02, p=0.774). However, significant indirect effects were observed; paternal family health positively influenced subjective well-being through marital satisfaction (β=0.37, p=0.003), and parental stress negatively influenced subjective well-being through marital satisfaction (β=-0.08, p=0.009). Thus, marital satisfaction mediated the relationships between both paternal family health and parental stress, respectively, on subjective well-being among married students (Table 3).

Table 3. Direct and indirect path in the final model

Discussion

The present study examined the mediating influence of marital satisfaction on the relationships linking paternal family health and parental stress to subjective well-being among married student participants. There was an inverse association between parental stress and marital satisfaction, indicating that heightened parental stress negatively impacts marital satisfaction. This result aligns with prior research, notably Dong et al. [30], reporting a negative correlation between childcare pressure and stress and marital satisfaction. Similarly, Brisini and Solomon [31] found that relational distress, characterized by diminished effective reasoning and elevated parenting stress, is associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction.

This relationship can be attributed to the multifaceted challenges parents encounter during child-rearing, including the transition from spousal to parental roles and the financial strain associated with parenting. Successfully navigating these responsibilities directly influences the quality of this life stage. Even in initially harmonious marriages, inadequate management of these tasks can lead to a decline in marital quality and eventual relationship deterioration. Research has identified parental stress as a significant contributor to reduced marital satisfaction during this period [30]. Conversely, couples experiencing high marital satisfaction are more inclined to provide mutual emotional support. This support can mitigate feelings of isolation and anxiety stemming from parental responsibilities. Parental feelings of being understood and supported by their partners enhance their capacity to effectively manage the demands of parenting.

There was also a significant relationship between paternal family health and marital satisfaction. This finding aligns with observations by Arianfar and Rasouli [20], reporting a direct influence of paternal family health on marital satisfaction. However, Hejazi et al. [32] report a contrasting result, indicating a negative association between family-of-origin health and marital satisfaction.

To elucidate this finding, attachment theory posits that children develop coping strategies and distress regulation through interactions with primary caregivers, seeking intimacy and closeness consistent with these experiences [32]. Consequently, family-of-origin health appears to indirectly enhance marital satisfaction by shaping parental marital dynamics. Furthermore, Bowen’s multigenerational theory suggests that individuals acquire fundamental interpersonal relationship patterns within their families of origin, and marital and familial challenges often reflect unresolved relational issues from these formative experiences. Communication patterns within the family of origin, including interaction styles, mutual understanding, and decision-making processes, influence individuals’ ability to adapt to future relationships and extra-familial contexts [20]. In essence, individuals with healthy family-of-origin experiences are more likely to demonstrate attentiveness to their spouse’s needs and expectations, engaging in empathetic and constructive interactions, which ultimately foster marital satisfaction. Moreover, healthy family-of-origin dynamics facilitate constructive conflict resolution, contributing to heightened marital satisfaction.

There was a positive association between marital satisfaction and subjective well-being, indicating that elevated marital satisfaction predicts greater subjective well-being. This finding is consistent with prior research, including a study by Ansari Ardali et al. [33], reporting a positive correlation between marital satisfaction and well-being.

This association can be explained by the role of marital satisfaction in facilitating a balance between personal needs and spousal/parental responsibilities. This equilibrium not only contributes to successful marital functioning but also supports individual personal growth. Consequently, it leads to enhanced interpersonal relationships, reduced relational stress, increased marital happiness, and strengthened emotional bonds. This synergy of relational satisfaction and personal development appears to fulfill the prerequisites for enhancing subjective well-being [33].

A supportive spouse serves as a critical source of social support, positively correlating with subjective well-being. However, not all marriages are more advantageous than singlehood in terms of subjective well-being. Marital conflict, separation, or divorce can precipitate psychological and health problems. Remaining in an unsatisfactory marriage is significantly associated with diminished happiness, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and overall health, as well as increased psychological distress. Furthermore, remaining in an unhappy marriage is often more detrimental than divorce, as individuals dissatisfied with their marriages report lower contentment compared to divorced or remarried individuals. Thus, maintaining a satisfying marital relationship is crucial for achieving, enhancing, and sustaining high subjective well-being.

There was also a significant association between paternal family health and subjective well-being. This result is consistent with observations by Kuo and Chiu [34], indicating that family atmosphere directly impacts individual well-being. Likewise, the findings of Pitonyak et al. [8], which link functional patterns of the family of origin to health and well-being, and Crandall et al. [35], which associate negative familial mental impacts with increased psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety (negative aspects of mental health and well-being), corroborate this finding.

To elucidate this, subjective well-being encompasses the absence of mental distress, overall life satisfaction, and the pursuit of self-actualization. It is recognized as a critical factor in resilience against psychological harm and illness. However, as evidence indicates, it is also influenced by various factors, including family health. Paternal family health fosters subjective well-being among family members by establishing a supportive, stable, and meaningful environment. This influence operates through mechanisms, such as emotional support, stress management, modeling healthy behaviors, and promoting a sense of belonging, thereby predicting and enhancing subjective well-being. Consequently, attending to paternal family health not only improves familial relationships but also promotes the mental and emotional health of family members.

Furthermore, paternal family health is frequently associated with stability and structure. An environment characterized by clear rules, explicit expectations, and consistent daily routines provides children with a sense of security and predictability. This stability contributes to reduced anxiety and enhanced feelings of control over life, both of which are key determinants of subjective well-being [8]. Consequently, healthy families typically facilitate the early identification and management of psychological issues. This proactive intervention may contribute to the maintenance of subjective well-being.

The current study’s findings revealed no significant direct relationship between parental stress and subjective well-being. This result diverges from previous research, including a study by Sharda et al. [36], but aligns with observations by Russell et al. [37].

This discrepancy can be attributed to the complex, multidimensional nature of subjective well-being, which is influenced by a confluence of factors, including interpersonal and environmental interactions. Consequently, parental stress alone may not serve as a precise predictor of subjective well-being. Other salient factors, such as social support from the family of origin and the quality of the marital relationship, play crucial roles. For instance, parents with robust social support networks [8] or high marital satisfaction may exhibit higher levels of subjective well-being, even in the presence of parental stress. Furthermore, individual psychological resources, such as coping strategies and emotion regulation, significantly modulate the association between parental stress and subjective well-being. Effective coping mechanisms can attenuate the adverse effects of stress [37]. Mindful parenting and positive mental health are also associated with diminished parental stress. It is plausible that individuals exhibit heterogeneous responses to stress. Some parents may perceive stress as a catalyst for growth and demonstrate enhanced adaptive capacity, while others may experience a decline in subjective well-being under stress. These variations are contingent upon other influential psychological factors.

The indirect path analysis revealed that marital satisfaction mediates the relationship between paternal family health and subjective well-being. This result aligns with prior research, including a study by Iwasa et al. [38], demonstrating the mediating role of marital satisfaction in the association between family dynamics and subjective well-being.

This finding can be explained by the dual influence of family support, encompassing both instrumental and emotional dimensions, on subjective well-being. Marital satisfaction acts as a significant mediator in this process, suggesting that the quality of the marital relationship amplifies the beneficial effects of family support on psychological well-being. Moreover, the quality of family life is substantially linked to couples’ subjective well-being, and a satisfying marital relationship can create a conducive environment for enhancing well-being by potentiating positive family effects [38]. Specifically, marital satisfaction functions as a critical intermediary through which paternal family health impacts family members’ subjective well-being. A healthy and supportive paternal family facilitates constructive interactions, rooted in healthy communication patterns, within marital relationships, thereby fostering increased marital satisfaction. Subsequently, elevated marital satisfaction contributes to enhanced subjective well-being by enabling couples to mitigate stress and cultivate happiness in their shared lives.

There was an indirect relationship between parental stress and subjective well-being, mediated by marital satisfaction. Specifically, parental stress was found to negatively influence marital satisfaction, which subsequently had a positive impact on and enhanced subjective well-being. This result is consistent with prior research documenting the adverse effects of parental stress on marital satisfaction [30, 31] and the beneficial effects of marital satisfaction on subjective well-being [33].

This mediation can be explained by the observation that couples exhibiting higher marital satisfaction tend to address parenting and spousal challenges with greater support and responsibility, leading to a reduction in parental stress. The attenuation of anxiety and tension associated with parental responsibilities enables parents to manage child-rearing demands more effectively. Consequently, marital satisfaction, by buffering subjective well-being against the negative impacts of parental stress, creates a conducive environment for enhancement.

Several limitations warrant consideration. Firstly, the use of convenience sampling in this study may have introduced potential bias into the findings. Secondly, the exclusion of male participants and the consequent inability to account for gender differences represent significant limitations that should be acknowledged.

In conclusion, this study elucidates the complex interplay between paternal family health, parental stress, marital satisfaction, and subjective well-being within the studied population. The significant positive direct influence of paternal family health on subjective well-being underscores the importance of positive familial dynamics in fostering individual well-being. Furthermore, the mediating role of marital satisfaction in this relationship highlights its crucial function as a conduit through which healthy family environments translate into enhanced subjective well-being. Conversely, while parental stress did not directly impact subjective well-being, its significant negative indirect influence through marital satisfaction suggests that parental stress erodes marital satisfaction, subsequently diminishing subjective well-being. The robust positive direct relationship between marital satisfaction and subjective well-being reinforces the established literature on the critical role of marital quality in promoting individual psychological health. These findings collectively emphasize the systemic nature of well-being, where familial and relational factors interact to shape individual subjective experiences.

Conclusion

Paternal family health positively affects subjective well-being, mediated by marital satisfaction, while parental stress negatively impacts well-being through reduced marital satisfaction.

Acknowledgments: The researchers would like to thank all the individuals who participated in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This study received ethical approval from the Ethical Committee of the Islamic Azad University-Ahvaz Branch (reference code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1402.161).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Nadi E (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Bakhtiarpour S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Makvandi B (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/ Statistical Analyst (20%); Asgari P (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This study did not receive any funding.

Keywords:

References

1. Campbell F, Blank L, Cantrell A, Baxter S, Blackmore C, Dixon J, et al. Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1778. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-022-13943-x]

2. Paredes MR, Apaolaza V, Fernandez-Robin C, Hartmann P, Yañez-Martinez D. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on subjective mental well-being: The interplay of perceived threat, future anxiety and resilience. Personal Individ Differ. 2021;170:110455. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110455]

3. Shannon S, Breslin G, Prentice G, Leavey G. Testing the factor structure of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale in adolescents: A bi-factor modelling methodology. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113393. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113393]

4. Bersia M, Charrier L, Berchialla P, Cosma A, Comoretto RI, Dalmasso P. The mental well-being of Italian adolescents in the last decade through the lens of the dual factor model. Children. 2022;9(12):1981. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/children9121981]

5. Li W, Song Y, Zhou Z, Gu C, Wang B. Parents' responses and children's subjective well-being: The role of parent-child relationship and friendship quality. Sustainability. 2024;16(4):1446. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/su16041446]

6. Liu Y, Li L, Miao G, Yang X, Wu Y, Xu Y, et al. Relationship between children's intergenerational emotional support and subjective well-being among middle-aged and elderly people in China: The mediation role of the sense of social fairness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19(1):389. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19010389]

7. Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):192. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y]

8. Pitonyak JS, Kelly S, Caroline U, Jirikowic T. Using a health promotion approach to frame parent experiences of family routines and their significance for health and well-being. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2022;15(4):335-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/19411243.2021.1983499]

9. Grüning Parache L, Vogel M, Meigen C, Kiess W, Poulain T. Family structure, socioeconomic status, and mental health in childhood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;33(7):2377-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00787-023-02329-y]

10. Dunst C. Meta-analysis of the relationships between the adequacy of family resources and personal, family, and child well-being. Psychol Res. 2021;9(1):35-57. [Link] [DOI:10.15640/jpbs.v9n1a5]

11. Thomas PA, Liu H, Umberson D. Family relationships and well-being. Innov Aging. 2017;1(3):igx025. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/geroni/igx025]

12. Behere AP, Basnet P, Campbell P. Effects of family structure on mental health of children: A preliminary study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39(4):457-63. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/0253-7176.211767]

13. Sharda E. Parenting stress and well-being among foster parents: The moderating effect of social support. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2022;39:547-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10560-022-00836-6]

14. Barreto S, Wang S, Guarnaccia U, Fogelman N, Sinha R, Chaplin TM. Parent stress and observed parenting in a parent-child interaction task in a predominantly minority and low-income sample. Arch Pediatr. 2024;9(1):308. [Link] [DOI:10.29011/2575-825X.100308]

15. Choi C, Lee J, Yoo MS, Ko E. South Korean children's academic achievement and subjective well-being: The mediation of academic stress and the moderation of perceived fairness of parents and teachers. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;100:22-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.004]

16. Maroufizadeh S, Hosseini M, Rahimi Foroushani A, Omani-Samani R, Amini P. The relationship between perceived stress and marital satisfaction in couples with infertility: Actor-partner interdependence model. Int J Fertil Steril. 2019;13(1):66-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12888-018-1893-6]

17. Randall A, Bodenmann G. Stress and its associations with relationship satisfaction. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:96-106. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.010]

18. Hashemi SF, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Nataj AH, Ganji J. Factors associated with marital adjustment in couples: A narrative review. Curr Psychosom Res. 2024;2(2):73-86. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/cpr.2.2.193.1]

19. Keshavarzafshar H, Bahonar F, Jahanbakhshi Z, Abdolinaser N. Relationship of marital affairs based on interpersonal relationships and emotional self-regulation with the mediating role of self-esteem in Iranian couples. Cult Psychol. 2021;5(2):97-117. [Persian] [Link]

20. Arianfar N, Rasouli R. Design the online shopping model for women structural equation modeling of the predicting marital satisfaction on the health of the main family and the mediatory variable of lovemaking styles. J Woman Fam Stud. 2019;7(1):139-57. [Persian] [Link]

21. Lee E, Kim SI, Jung-Choi K, Kong KA. Household decision-making and the mental well-being of marriage-based immigrant women in South Korea. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0263642. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0263642]

22. Keyes CLM, Magyar-Moe JL. The measurement and utility of adult subjective well-being. In: Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2003. p. 411-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/10612-026]

23. Ebrahimi L, Rostami Y, Mohamadlou M. The Mediating role of internalizing problems on the relationship between emotional well-being and externalizing problems of divorced women in Zanjan. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J. 2019;9(3):10-20. [Link] [DOI:10.52547/pcnm.9.3.10]

24. Hovestadt AJ, Anderson WT, Piercy FP, Cochran SW, Fine M. A family-of-origin scale*. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985;11(3):287-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1985.tb00621.x]

25. Rajabi G, Naderi Nobandegani Z, Jelodari A. Exploratory factor structure of the Persian version of the family of origin scale. Psychol Model Method. 2018;8(29):237-52. [Persian] [Link]

26. Abidin RR. The determinants of parenting behavior. J Clin Child Psychol. 1992;21(4):407-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1207/s15374424jccp2104_12]

27. Mohammadipour S, Dasht Bozorgi Z, Hooman F. The role of mental health of mothers of children with learning disabilities in the relationship between parental stress, mother-child interaction, and children's behavioral disorders. J Client Cent Nurs Care. 2021;7(2):149-58. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.7.2.362.1]

28. Fowers BJ, Olson DH. ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale: A brief research and clinical tool. J Fam Psychol. 1993;7(2):176. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.176]

29. Arab Alidousti A, Nakhaee N, Khanjani N. Reliability and validity of the Persian versions of the ENRICH marital satisfaction (brief version) and Kansas marital satisfaction scales. Health Dev J. 2015;4(2):158-67. [Persian] [Link]

30. Dong S, Dong Q, Chen H. Mothers' parenting stress, depression, marital conflict, and marital satisfaction: The moderating effect of fathers' empathy tendency. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:682-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.079]

31. Brisini KSC, Solomon DH. Distinguishing relational turbulence, marital satisfaction, and parenting stress as predictors of ineffective arguing among parents of children with autism. J Soc Pers Relatsh. 2020;38(1):65-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0265407520958197]

32. Hejazi SS, Jalal Marvi F, Nikbakht S, Akaberi A, Kamali A, Ghaderi M. Relationship between the family of origin health and marital satisfaction among women in Bentolhoda hospital of Bojnurd: A study in the north east of Iran. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J. 2021;11(4):46-54. [Link] [DOI:10.52547/pcnm.11.4.46]

33. Ansari Ardali L, Makvandi B, Asgari P, Heidari A. The relationship between spiritual intelligence and marital satisfaction with psychological well-being in mothers with special-needs children. Casp J Pediatr. 2019;5(2):364-9. [Link]

34. Kuo HL, Chiu YW. Stress and coping behavior exhibited by family members toward long-term care facility residents while hospitalized. Healthcare. 2024;12(20):2022. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare12202022]

35. Crandall A, Daines C, Barnes MD, Hanson CL, Cottam M. Family well-being and individual mental health in the early stages of COVID-19. Fam Syst Health. 2021;39(3):454-66. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/fsh0000633]

36. Sharda EA, Sutherby CG, Cavanaugh DL, Hughes AK, Woodward AT. Parenting stress, well-being, and social support among kinship caregivers. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;99:74-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.025]

37. Russell BS, Adamsons K, Hutchison M, Francis J. Parents' well-being and emotion regulation during infancy: The mediating effects of coping. Fam J. 2021;30(1):4-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/10664807211022230]

38. Iwasa H, Yoshida Y, Ishii K. Association of spousal social support in child-rearing and marital satisfaction with subjective well-being among fathers and mothers. Behav Sci. 2024;14(2):106. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/bs14020106]